American History for Truthdiggers: The Slow, Perilous Shift to Emancipation

In 1861-65, Americans waged a war among themselves that remains the bloodiest in U.S. history. It began as a fight to preserve the Union but morphed into an abolitionist war to free 4 million men, women and children from bondage. An 1890 lithograph, “The Storming of Fort Wagner,” shows Col. Robert Gould Shaw and a handful of other Union officers—all white—leading the all-black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in attacking the South Carolina fortification.

An 1890 lithograph, “The Storming of Fort Wagner,” shows Col. Robert Gould Shaw and a handful of other Union officers—all white—leading the all-black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in attacking the South Carolina fortification.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 17th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 17 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16.

* * *

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.” —President Abraham Lincoln, in a letter to the abolitionist Horace Greeley (Aug. 22, 1862)

It is nearly impossible to illustrate the magnitude of the American ordeal of civil war. It is not just the hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians killed, but the fact that this war—perhaps more than any other—utterly transformed the United States. The bookshelves simply overflow with fascinating military histories of the conflict, and I’ll leave that part of the story to their distinguished authors. Rather, let us here examine how, in the course of just four years, the war moved from being dedicated solely to the preservation of the Union to becoming a war of liberation to emancipate slaves.

How, in other words, did President Lincoln move from his above quote—declaring he would do nearly anything with the slaves (including leaving them in bondage) in order to preserve the Union—to the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and, eventually, the 13th Amendment constitutionally abolishing slavery (1865)? What’s certain is that Lincoln himself may have transformed—for both tactical and moral reasons—as a brutal war moved him squarely into the abolitionist camp. This is perhaps the most profound tale of this horrific war: the one with the most transformative impacts.

The Myth of Union Invincibility

It’s often said that the North held all the strong economic, political and military cards at the start of this war. And, indeed, it did—on paper. The Union states had the vast majority of the (white) population, nine-tenths of the manufactured goods, seven-tenths of the miles of railroad tracks, nine-tenths of the merchant ships and seven-tenths of the grain production. The North also received most of the country’s annual immigration and had eight-tenths of the nation’s banking flow. By these measures, it seemed the South didn’t stand a chance.

But a closer look narrows the gap between the two belligerents. The North had essentially no army—its paltry regiments were mostly spread across the vast western interior fighting Indians. Furthermore, some of the most able U.S. Army officers—one thinks of Robert E. Lee, T.J. “Stonewall” Jackson and James Longstreet—quickly resigned their commissions and joined the new Confederate army. That army, of course, was mobilized rather quickly because it had a head start. After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, spooked Southerners from Virginia to Texas formed militias to stave off perceived threats of slave rebellion. Many of these local militiamen would form the core of the future Confederate armies.

Perhaps the biggest equalizer, however, was the matter of opposing war aims. The Union could win only if it conquered and occupied much of the South. A win for the South, on the other hand, meant simply not losing. This is a much easier, and defensive, task. The Union could count on long supply lines (which had to be guarded) and frequent guerrilla attacks by the Confederates at its rear. The South fought on familiar turf and with much shorter supply lines. And the population numbers were themselves deceptive. Though the North counted seven-tenths of the white population, the South counted nearly 4 million slaves. These laborers kept the Southern agrarian economy churning and freed up millions of potential soldiers for the Confederacy. Conversely, Northerners, out of fear of crippling their economy, couldn’t mobilize nearly so high a percentage of the workforce.

Many Southerners also argued that its rural population was more martial and effective than the supposedly effete Yankees. Some even claimed that just a single Southerner could “whoop 10 Yankees!” Though the South met early battlefield success and was generally better led during the war’s early campaigns, such conceited proclamations would be proved wrong. It turned out that there was enough (often foolhardy) valor on both sides, as men killed and died with a discipline that is shocking to the modern reader. In the end, nothing was inevitable, neither Union victory nor Southern defeat, but by 1862 one thing seemed certain: It was to be a long, hard war.

For Union!: Lincoln Walks the High Wire (1861-62)

President Lincoln was obsessed with Kentucky. Well, he had been born there. But there was far more to it. After all, not every slave state had seceded. Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware stayed in the Union—in some cases only just. Lincoln knew he needed to keep the so-called border states on the Union side, or at least neutral. Many lateral (east/west) railroad lines ran through the western border states and would be vital to shifting troops from theater to theater. Maryland and Delaware, along with already seceded Virginia, surrounded the Union capital, Washington, D.C. The president’s very safety was at stake.

So it was that Lincoln’s desire to keep the border states in the Union informed the president’s strategic thinking in the war’s first year. Lincoln had to downplay the abolitionist sentiments of his Republican Party and reassure Northern Americans—most of them wildly racist—that this war was for union, not a crusade against slavery. In keeping with this strategy, in the war’s early months most Union commanders were ordered to return runaway slaves and enforce the Southerners’ rights to their “property.”

Lincoln didn’t want and, he thought, couldn’t afford a crusade. What was needed was a quick victory, and a limited war that didn’t too badly damage Southern property or increase border state sympathy for the Confederacy. Initially, Lincoln called for only 75,000 three-month volunteers, and this is telling. One grand victory and the seizure of the Confederate capital in nearby Richmond, Va., might just end the war in one fell swoop. Of course, it was not to be. The green Union Army was out-led and, ultimately, outfought at the July 1861 Battle of Bull Run, near Manassas Junction, Va., and fled back to the District of Columbia in disarray.

In Tennessee and Mississippi, an unknown, disheveled general named Ulysses S. Grant—who had failed in most of life’s endeavors and been cashiered from the regular Army years before for drunkenness—met with more success (he would eventually lead all Union armies). Still, the rebels had generally acquitted themselves well in the war’s early years. It was to be a long war. Union strategy would have to change. As Lincoln wrote, “We must change tactics or lose the game.” It was time to strike the economic and cultural heart of the Confederacy: the institution of slavery.

‘As He Died to Make Men Holy, Let Us Die to Set Men Free’: Emancipation Comes at Last

Lincoln was stuck between political forces. The opposition Democrats in the North were decidedly against emancipation of the slaves, as was much of the Northern population (especially Irish immigrants). His own Republicans—especially the “radical wing”—on the other hand, were becoming frustrated with Union military defeats and Lincoln’s unwillingness to attack slavery. But Lincoln was personally edging ever closer to the “radical” position, for reasons of “military necessity.” Congress, in July of that year, had passed the Confiscation Act of 1862, which held that Union military officers were no longer obliged to return runaways to Southern slaveholders. Congress knew, as did Lincoln and his commanders, that slavery was the core of the Southern war machine. Slaves dug trenches, built forts, raised crops and enabled millions of white men to head to the battle front. Something had to be done to strike a blow to the South’s war-making capacity. An attack on slavery seemed to be just the thing.

Unfortunately, Lincoln felt he first needed a battlefield victory before issuing an Emancipation Proclamation. And, for a year, his armies in the vital Eastern theater had known nothing but defeat: at Bull Run (1861), the Peninsula Campaign (1862), the Shenandoah Valley (1862) and Second Bull Run (1862). Then, in September 1862, the effective, victorious Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee took his Army of Northern Virginia northward and invaded Maryland. He hoped to turn Maryland into a rebel state, gain international recognition for the Confederacy and, perhaps, end the war. On Sept. 17, 1862, at Antietam Creek, Lee was (just barely) defeated and forced back into Virginia. Though the ever-cautious Union Gen. George B. McClellan had failed to trap and destroy or at least meaningfully pursue Lee’s army (despite having found a misplaced copy of the Confederate battle plan!), Lincoln had the “victory” he needed.

Soon afterward, he issued probably one of the most profound, questionably legal and consequential executive edicts of all time: the Emancipation Proclamation. It declared that on Jan. 1, 1863, all slaves held in the rebellious states were “then, thenceforward, and forever free!” So, how many slaves did Lincoln free in January 1863? Zero. The edict didn’t touch the slaves in border states (Lincoln still needed to keep these states in the Union) and applied only to slaves in regions actively in rebellion. Of course, the Confederates reigned in these areas and weren’t about to free their slaves. In the end, the proclamation was a war measure, not a humanitarian decree. But it did change one thing. The Union Army would transform overnight into an army of liberation wherever it marched.

This much, too, is certain: There would have been no Emancipation Proclamation had the war not lasted so long and turned so bloody. It was the death of whites by the tens of thousands that convinced the Union to free the blacks. The irony, of course, was that if the Union had won at Bull Run, or if the Union’s commander during 1862, Gen. McClellan, would have seized Richmond in July 1862 (as he nearly did), then the war might have ended with slavery intact. After all, emancipation was not yet a stated war aim, and it is likely that a coalition of Southerners, border staters and Northern Democrats would have negotiated reunion without emancipation. Who knows how long slavery might then have persevered in the American South.

Who (Really) Freed the Slaves?

Ask an American on the street today “Who freed the slaves?” and nine times out of 10 the answer will be “Abe Lincoln, of course.” But that’s not strictly true. Lincoln did, it must be said, generally abhor the institution of slavery, but he was extraordinarily cautious in its abolition. His Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free a single slave on the day it took effect, Jan. 1, 1863. And it wasn’t just “military necessity” that had provoked the decision. From the earliest days of the war, the slaves, if not the Northern whites, were totally sure this was a war for abolition. By the tens of thousands they risked their lives to escape to Union lines. They placed the question of emancipation—of what exactly was to be done with these “contrabands” of war, as the slaves were termed—on the agenda of the Union Army and, by extension, the U.S. government.

How this process worked can be made clear with a simple vignette, undoubtedly repeated thousands of times during the war. A family of runaway slaves—man, woman and child—escapes a plantation and enters Union-held territory. They meet a lowly private on guard duty. The soldier is no abolitionist; heck, he has probably never met many black people. He certainly doesn’t see them as his equal. Still, he catches the look in the poor child’s eyes and doesn’t want to be responsible for turning these slaves away. So he asks his lieutenant what to do, who asks the captain, who asks the colonel, who asks the general, who … eventually asks President Lincoln. What exactly is the policy of the U.S. government toward these human “contrabands”? The question becomes public, is debated in Congress, on the streets, in countless taverns.

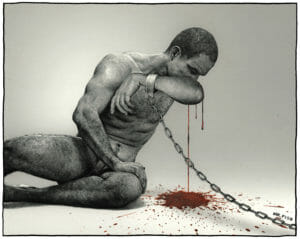

Most standard histories ignore this facet of the war and deny agency to the millions of black slaves, most of whom are portrayed as victims and then grateful benefactors. Only they were so much more. Seen in this light, it was the slaves, through their many thousands of dangerous escapes, who freed themselves, by flooding the Union Army lines both before and after the famed Emancipation Proclamation.

Whither Civil Liberties?

The Civil War probably did more to expand federal and presidential power than any other war in American history. Although both the Union and Confederacy were republics and ostensible democracies, each soon found that exigencies of war would force them to curtail civil liberties and centralize governance. The latter was particularly ironic in the “states rights”-obsessed South. Lincoln, in response to anti-conscription and anti-war riots, called out the Army in more than a few cities, suspended habeas corpus and imprisoned many anti-war figures. He even banished one Ohio politician to the South! Some of these measures have been, rightfully, criticized by later scholars.

But context matters. Lincoln had a war to win, political enemies at his rear and an Army that had known mostly defeat for two full years. Furthermore, the draft riots were a genuine threat and a reflection of Northern racism (and unhappiness about fighting for black freedom), especially among the Irish. For example, in the New York riots of July 1863, angry mobs attacked blacks throughout the city, killing more than 100 and prompting Lincoln to call in federal troops fresh from the Battle of Gettysburg to suppress the five-day melee. Lincoln’s critics, who took to calling him “King Abraham,” “a Caesar” and a tyrant, remained angry throughout the war. They resented the implementation of a military draft (the first of its type), his transformation of the war into one of emancipation, declarations of martial law and his suspension of civil liberties. However, the American people, by and large, stood by Lincoln and gave him (a surprising) victory in his bid for re-election in 1864.

The actions of Confederate President Jefferson Davis were even more ironic. His was a republic supposedly founded on states’ rights and in opposition to centralized control. And yet it was the Confederacy that first passed a conscription law and drafted its white population into military service.

Interestingly, a “Twenty-Negro Law” exempted substantial slaveholders from conscription, resulting in opposition by some to what was called a “rich man’s war and poor man’s fight.” The government in Richmond could temporarily commandeer slaves for war labor. Furthermore, high taxation (which the Southern Democrats supposedly abhorred) combined with food shortages to cause notorious “bread riots” in Richmond and mass desertions from the South’s armies. In some regions, deserters and draft dodgers formed armed militias that essentially ruled certain counties as independent nations.

The story was the same, North and South, as it often is: “Military necessity” and a long, bloody war curtailed individual freedom.

Carnage: Waging the Civil War

It was a bloodbath. From start to finish, thousands upon thousands of Americans—clad in blue or gray—fell dead or maimed on the field of battle. Few had predicted such a massive bloodletting; after all, this was to be a 90-day war. Instead, it lasted more than four years. The American Civil War was by far the costliest in American history. Some 600,000 died, if not more—equivalent to more than the American fatalities of the two world wars taken together. On a single day at the Battle of Antietam (Sept. 17, 1862), more men were killed and wounded on both sides than in all previous American wars. More Union men became casualties that day than the number that would fall on D-Day in 1944.

The primary cause of all this death and destruction (besides the devotion of both sides) was the rifled musket. In previous wars, the United States and other belligerents generally used smoothbore muskets, which were far less accurate. Rifling a musket increased its range and accuracy fourfold and made the defense the far stronger tactical position. The rifle also decreased the offensive value of artillery, as gunners could now be picked off when the cannons were brought forward. Furthermore, traditional cavalry charges became a thing of the past, since bullets took down horses and riders long before they could reach the infantrymen’s lines.

Still, there was more to it than mere technology. The tactics of this war had not yet caught up with the technological advances. Most officers on both sides, trained in Napoleonic tactics at West Point, preferred the offensive to the defensive. They were taught to be aggressive and to seek out and destroy the enemy’s main force. Few recognized the transformational power of the rifle soon enough to stray from the “close-order column” tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, and they marched their men straight into the deadly maelstrom of enemy fire. Though often misguided, these officers were brave; there is no question. Colonels and generals led from the front, and in the Civil War, a general was more likely to be killed than a private. The inverse has tended to be true ever since. By war’s end, after years of failure to recognize the tactical revolution that had been unleashed, both sides had shifted to entrenchments and defensive fortifications. Unfortunately, by then, hundreds of thousands had fallen in foolish close-order charges.

We Are Men: Black Soldiers in the Civil War

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US, let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.” —A speech by abolitionist and former runaway slave Frederick Douglass at National Hall in Philadelphia (July 6, 1863)

Few could have imagined it. Most Southerners and plenty of Northerners couldn’t have foreseen the mass arming of blacks and their service in the armies of the federal republic! But this is exactly what occurred, as early as 1862, when Congress gave its approval. The decision was driven by two main forces: one, military necessity, and, two, the clamoring of blacks and runaway slaves themselves to serve the Union. And enlist they did, in record numbers. Though just 1 percent of the prewar Northern population, blacks eventually constituted 10 percent of Union Army volunteers. Furthermore, 85 percent of the North’s of-age black population enlisted.

All told, by war’s end, 180,000 blacks would serve the Union. They were paid less than white soldiers, treated poorly by many white troopers, served under white officers and were initially kept behind the lines for humiliating menial labor. Still, the valor of the black troops cannot be overestimated. By 1865, 20 percent of the 180,000 black soldiers had died, a casualty rate much higher than among their white brothers in arms. Many black soldiers came from the border states, for enlisting in the Army was the only sure way to freedom in regions where slavery remained legal after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Tens of thousands of others were runaways, only recently held in bondage.

These men knew exactly what they were fighting for. The war was no abstraction for a runaway slave. In the Army they could contribute to a victory they hoped would bring their permanent salvation. They also found many other things in the Army: the dignity of service; a transformation of their self-image; and, among some at least, a new respect in the collective national opinion. Still, serving in a black regiment was dangerous for soldier and officer alike. The Confederates were appalled by the sight of blacks armed and in uniform. Some Confederate units refused to take black prisoners and had a policy of shooting captured black soldiers and their hated white officers. Besides, with much to prove on the field of battle, combat could be extraordinarily perilous.

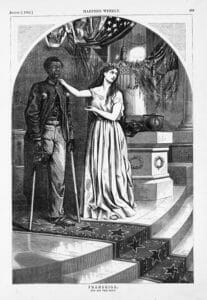

One of the first and most famous black regiments formed was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Its colonel was the 26-year-old Robert Gould Shaw, the son of prominent abolitionist parents in Boston. As a Massachusetts regiment, raised partly at the behest of Frederick Douglass and other famous local abolitionists, the 54th was the North’s “showcase black regiment.” In July 1863, the regiment volunteered to lead the assault on the formidable Fort Wagner in South Carolina. In the heroic, and ultimately unsuccessful, attack, nearly half the regiment became casualties and Shaw was killed charging the fort’s parapet. Though the attack failed, the exploits of the 54th resonated across the North. The Atlantic Monthly declared, “Through the cannon smoke of that dark night [at Fort Wagner], the manhood of the colored race shines before many eyes that would not see.”

The Confederates threw the body of Col. Shaw into the pit of a mass grave along with hundreds of his enlisted men. When a Confederate officer supposedly replied to a request for Shaw’s body with the taunt “We have buried him with his niggers,” Shaw’s proud father replied, “We hold that a soldier’s most appropriate burial-place is on the field where he has fallen.” Col. Shaw still lies with his men in that pit on a South Carolina island.

Lincoln’s Final Act: The 13th Amendment

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” —Section I, 13th Amendment to the Constitution (1865)

By January 1865, the war was finally nearing its end. More than half a million soldiers were dead, and nearly 200,000 blacks wore the uniform of the Union. Still, President Lincoln felt there remained work to be done aside from achieving victory in the war. During a lame-duck session of Congress, he fought hard and pushed the 13th Amendment through the House of Representatives on its way to ratification. He was advised not to do so. Some thought it would motivate the South to fight on, others, that it would alienate Lincoln’s supporters in the slave-laden border states; plenty just plain disagreed with the final abolition of slavery.

Nevertheless, Lincoln proceeded. He did so, mainly, because he feared the war would end before slavery was on its way to abolishment. His Emancipation Proclamation, after all, was an executive war measure, sanctioned not by Congress but by presidential fiat. Though the proclamation declared the slaves were “forever free,” might not the courts determine after the war that the edict was unconstitutional or no longer in effect? Might then, as Lincoln feared most, the runaway slaves that donned the Union blue be rendered slaves once again at war’s end? Here Lincoln demonstrated his true mettle. He and his supporters lobbied for the necessary votes, probably bribed their way to some, and eventually won passage of the amendment. Thus ended slavery everywhere. And, ironically, it was in loyal border states such as Delaware that it ended last—long after the Union Army had liberated the slaves of Alabama.

Emancipation and the 13th Amendment that followed constituted, by some economic measurements, the largest and quickest forced confiscation of property in world history and were, by their very nature, a major and complex undertaking. The achievement was profound, if unexpected. A war undertaken, by Lincoln’s own declaration, for preservation of the Union—regardless of the outcome for the slaves—had within four short years morphed into a conflict that abolished slavery once and for all. It was now the law of the land: “Neither slavery, nor indentured servitude … shall exist within the United States.” It was a long, hard road, but after half a century of effort, the once mocked abolitionists had achieved freedom for the slaves.

* * *

On April 14, 1865, just days after Robert E. Lee surrendered his army, Lincoln was assassinated in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., by the actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. In a tragedy truer than fiction, Lincoln would not see the Union to final victory. Nonetheless, by April 1865, Lincoln knew that victory was near—though it was not the sort of victory he had initially envisioned. He had hoped to quickly re-establish and preserve the Union without resorting to total war.

Instead, the carnage of Bull Run, the Peninsula campaign, Shiloh and other battles led him to see the bitter truth. Victory demanded that the old Union and the old South be destroyed and a new union reconstructed on its ashes. This would be the task at hand when the Confederacy surrendered. The nation had changed by 1865. The role and scope of federal power had forever increased; notions of race and citizenship had been reformulated. And, lastly, a new nationalism formed as Americans started to think of the federal Union as the paramount law of the land. Before the war, most Americans referred to these United States. After the conflict, almost all labeled this country the United States!

The war appeared to solve many things: the question of union, the legality of secession, even the existence of slavery. Yet so much more, so many unanswered questions, lay before Lincoln’s untested successor and the nation as a whole. How shall the Union be pieced together, and how would (or should) 4 million souls—recently held in bondage—be integrated into American society? The nation would have to be reconstructed, to be sure, but few knew quite what to do with the freed slaves. In the aftermath of civil war there existed an opportunity, a first chance, to legislate and enforce racial equality once and for all. Americans had only to seize the chance. Tragically, they would not.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

• James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle, and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 16: “Total War and the Republic, 1861-1865” (2011). • James M. McPherson, “The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era” (1998).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.