Delegates Process May Shift Because of COVID-19

The next stage in the 2020 process is county-level conventions where hundreds of activists, organizers and officials are expected to attend starting this month.Top Democratic Party officials are scrambling to figure out how to handle voting by crowds at their next big event of the 2020 presidential season: the county conventions where Democratic National Convention delegates start to be named.

“We are now in the season of actually selecting delegates,” said Elaine Kamarck, a presidential election scholar and member of the DNC Rules and Bylaws Committee from Massachusetts. “How that will happen is an open question.”

“The issue is that we are beginning the season where a lot of county and congressional district conventions are taking place to actually select people for the delegate slots,” she said. “That’s complicated because those are large meetings. States are busy trying to figure out what do they do with these [events]. Do they postpone them? How do you do these? By and large, we do not have actual people selected as delegates. We just have [candidate delegate] allocations.”

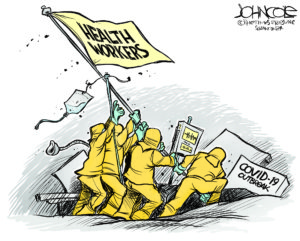

The national health emergency surrounding the eruption of the coronavirus has raised many questions about how 2020’s forthcoming elections will be held. In the four states that will be holding primaries on March 17—Arizona, Florida, Illinois and Ohio—state officials have been taking last-minute steps to minimize exposing voters. Those steps include moving polling places away from senior centers and regularly wiping down touch screen computers used by voters to cast ballots.

So far, government officials in only one state, Louisiana, have postponed their primary from early April to late June due to the virus. In Congress, Sen. Ron Wyden has proposed allocating funds to help states to vote by mail in the fall, as a way to lessen exposure to the virus during the voting process.

However, the next big events in the Democratic Party’s nominating process are the county-level conventions—starting in Iowa on March 21, moving to congressional district conventions on April 25 and a state convention on June 13. Attendees of these conventions tend to be the party’s activists, organizers and elected officials.

Ironically, some states holding these conventions are eyeing the use of electronic voting systems—even after digital systems failed or delayed the results in some important early 2020 contests—namely party-run caucuses in Iowa and Nevada, and the government-run primary in Los Angeles County, the nation’s largest voting jurisdiction. Democrats in Virginia were eyeing systems used by unions and trade associations in their elections, according to DNC officials following that process.

Stepping back, ex-Vice-President Joe Biden’s emergence as the Democratic frontrunner and the national health emergency have DNC officials hoping that the nominating season will begin to wind down after the March 17 primaries. (So far, the DNC has not made a decision to cancel their national convention in July.)

November Election Still on Track

The uncertainties unleashed by the pandemic have raised many questions about whether the 2020 national election will be held as scheduled—or how the voting would be done. The decision by Georgia’s Republican Governor, Brian Kemp, to cancel a state Supreme Court election and appoint a conservative justice, followed by Louisiana’s postponement of its 2020 primary, has underscored that concern.

However, party primaries, state-level contests and federal general elections are all different legal exercises, said Ned Foley, director of the election law program at Ohio State’s law school and author of Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States. The parties always get to pick their nominees, he said, citing U.S. Supreme Court precedents. Governors, on the other hand, have varying powers under state law to intervene in state elections.

For example, New York’s GOP Gov. George Pataki rescheduled voting after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, struck on a state primary day. In 2008, Florida Democratic Gov. Charlie Crist extended early voting to accommodate African American voters. Kemp’s move, in contrast, is a power grab amid a major public health crisis. But Foley’s main takeaway was that presidential elections have never been delayed.

“There was no delay in the [1864] election in the Civil War, and I think that’s very important,” he said. “The point here is not whether but how. America is going to have a 2020 election. America is committed to the idea of popular sovereignty—‘We the People’ as expressed in the Constitution—the question is how we do that in difficult times.”

Foley and other experts said that there still was time to plan for fall voting.

“We may need to make adjustments,” he said, citing Louisiana’s move. “The mere fact that an election has been postponed because of emergency health considerations is not a subversion of voter choice. It may be the best way to effectuate voter input and the right of the voters to choose who governs.”

But shifting to a vote-by-mail system isn’t necessarily a cure-all, said Ion Sancho, who for nearly three decades was supervisor of elections in Leon County, Florida, where the state capital is located.

“Mail ballots are the most labor-intensive [way to count votes], and the switch to them in 2020, as you well know, is causing delays in final results,” he said. “That is becoming increasingly evident. And that runs counter to one of the Republicans’ main goals, which is trying to end the election on election night. That is certainly their goal in Florida.”

Sancho, like others contacted, said that the county was in a period of great uncertainty, including how 2020’s elections will be conducted. But no expert said that the process would not continue. The question was what changes would be necessary, starting with 2020’s remaining primaries and the Democrats’ nominating process.

“We’re in such uncharted territory,” said Kamarck.

“I suppose we could try to do an electronic ballot,” she said, thinking aloud about what some state parties were now studying. “The Russians have no interest in who the delegates are at the [national] convention, frankly. I don’t think they would particularly care to mess with who is the delegate from the first congressional district of Virginia.”

This article was produced by Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

Steven Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has reported for National Public Radio, Marketplace, and Christian Science Monitor Radio, as well as a wide range of progressive publications including Salon, AlterNet, the American Prospect, and many others.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.