Ordinary Chauvinism and a Little-Known Massacre

Mexican writer Julian Herbert investigates a 1911 slaughter of Cantonese immigrants in Torreon, Mexico, and his country's history of violence. Graywolf Press

Graywolf Press

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

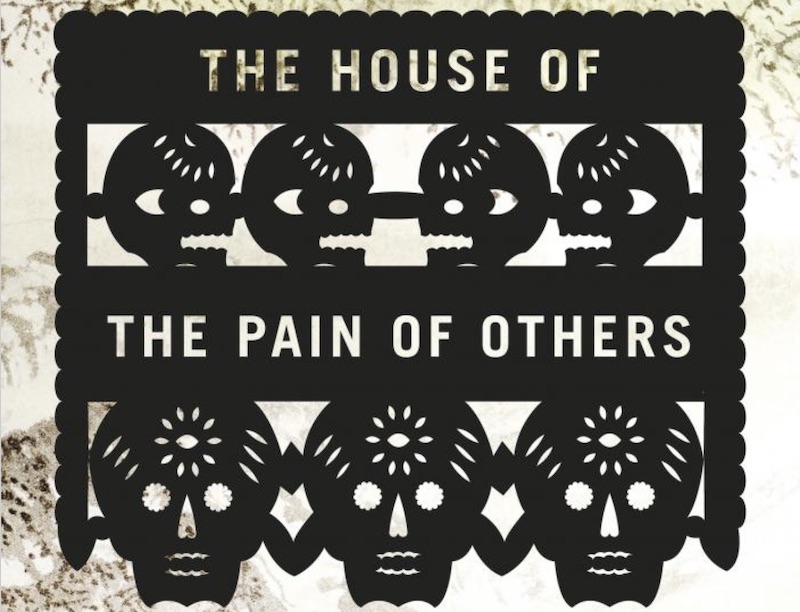

“The House of the Pain of Others: Chronicle of a Small Genocide”

A book by Julian Herbert. Translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

If you’re not familiar with 47-year-old Julian Herbert, you should be. Herbert is a literary magician of the highest order, a talented and innovative Mexican writer who writes with a biting rawness and candor. He is both a man of the street and a poet, a tough guy who has somehow managed to hold on to a piece of his tortured heart. Herbert reminds me of W.G. Sebald, another seductive illusionist, but Herbert has none of Sebald’s elitism or paranoia. Herbert is a wild man of sorts, provocative and challenging, perhaps to cover some sort of deep-seated insecurity.

In his searing memoir “Tomb Song,” he sits in a dilapidated hospital room in Mexico, his laptop wobbling on his knees, as he watches his mother die. Herbert’s mother was a prostitute. He never knew his father. His many siblings, all with different fathers who never stayed around, have scattered and he alone has come to comfort his mother. He enjoys having her to himself. She has been his one true love. He falls in and out of a half-sleep, finding himself remembering moments shared with his mother. There was a magical morning when she taught him how to write. But there were horrendous scenes too, of desolation and abandonment that have never left him.

He believes that writing will save him now. He will write her story and his own, and somehow through writing it the pain of these awful days will pass. He hopes so. His conflicting feelings about his mother is mirrored in his feelings about Mexico: He is open about the disgust he often feels with all that is Mexico, and yet he is unashamed to admit his attachment to his country.

Herbert’s memoir seems to be a precursor to his new book, “The House of the Pain of Others.” It allows us to understand the forces that drive him. “The House of the Pain of Others” attempts to dissect a genocide that took place in Torreon, Mexico, in 1911. The victims were hundreds of unarmed Cantonese Chinese immigrants who were brutally murdered, dismembered, and thrown into a mass grave with reckless abandon. Herbert attempts to discover all he can about this event, which for the most part has been erased from Mexican history. He never explains why he chose this undertaking, but we sense it is intricately tied to his search to understand himself and Mexico, and the poisons that still shatter the landscape.

Herbert finds some locals in Torreon who have heard about the massacre and speak to him nervously. Others laugh self-consciously. Many remain silent when he asks them directly if they know anything about what happened to the Chinese over a century ago. We realize, as we watch him watching others, that the victims have been silenced twice—at the moment of their gruesome deaths, and then again in Mexican memory.

The Cantonese immigrants who lived in Torreon at the time were railroad laborers, launderers, salesclerks, shoemakers, traders, and fishermen. They brought poppies with them to Mexico for the production of opium. The Mexicans were known not to be pleased with their presence. Many, Herbert claims, thought the Chinese to be dirty, uncouth, superstitious, unfriendly, and without humor. The Mexican Revolution was going on and some thought their deaths were simply collateral damage. But Herbert strongly suspects that this is a lie, that the Chinese immigrants were assassinated for no reason at all. He struggles to grasp what that says about the perpetrators of such a tragedy. What that says about Mexico and about himself. He knows this genocide is representative of something far more sinister and pervasive than what happened on that particular night, and he struggles to maintain the courage to really look at it head-on.

He examines the scanty evidence available to him. The first Mexican historian to write about the genocide, Eduardo Guerra, did so very briefly in 1932. Juan Puig added more context in 1992 but his account was challenged in 2005 by a doctoral student named Marco Antonio. But Herbert puts little credence in any of these accounts, sensing the distortions that run through their stories. Genocide resists deconstruction, particularly by the descendants of the perpetrators.

Herbert ponders the Mexican connection with violence. Their reckless flirtation with Nazism during the 1930s. Their ongoing obsession with wrestling and soccer. Even the “tropical sexuality” that often morphs into a carnal, degrading violence. He senses the reactionary impulses of his Mexican countrymen that still pulse beneath their faint cries for freedom and democracy. He wonders about the church’s effect on all of this. Do they constrain the barbarism or somehow encourage it? He is cognizant of the rampant xenophobia, chauvinism, and the regional antagonisms that have only grown more hostile with time. As he continues with his investigation, Herbert seems to make many around him uncomfortable with his inquiries.

He sometimes resorts to speaking to taxi drivers about the genocide. They look at him quizzically and say little. He sometimes imagines he can see the feet of the dead Chinese tramping through the city, and wonders if anyone else sees them too. He is envious of something elegant and restrained about the Chinese, but they seem foreign and unknowable. He is drawn to Confucianism, with its world so “complex and sublime that poets emerged who wrote verse of elegant simplicities that were Talmudic in their hidden complexities. ….” But he is more familiar with Mexican bleakness and pessimism.

Ultimately, Herbert comes to the conclusion that this slaughter was simply the result of a barbaric chauvinism that still simmers now, and that one day back in 1911 it erupted into total madness. He explains, “Pretending that the slaughter of the Chinese is completely at odds with local chauvinism would be like saying it’s impossible to get fries in a burger joint.” Could it really be that simple?

Herbert can’t let the mysteries that sparked this genocide go, and we can’t either. But we start to wonder about Herbert and what he isn’t able to see. He never really sees the Chinese people, dead or alive. They are merely phantom limbs for him, ghostly appendages that allow him to tell his story and the story of Mexico—an ugly story of chauvinism, machismo, and obtuseness blighted by bursts of violence.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.