Sex Trade’s Female Victims: ‘Spoiled Goods,’ Damaged Lives

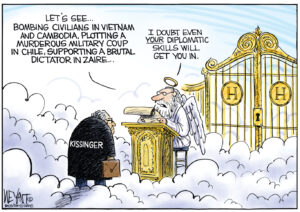

In Cambodia, South Africa and Albania—among other places—violence, poverty and extreme male dominance create a context in which men who pay for sex go uncensured, but the women and girls involved are permanently stigmatized. A hostess from Cyrcee Club in Phnom Penh leads the way to a nearby hotel. (Flickr / Creative Commons)

A hostess from Cyrcee Club in Phnom Penh leads the way to a nearby hotel. (Flickr / Creative Commons)

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

The women in the bar huddle together, talking and smoking, looking bored but tense. It is a hot evening in Phnom Penh, and I am in one of the notorious sex bar areas, hoping to find out all I can about commercial sexual exploitation in the country. I have gone undercover because the sex trade, whether legal or illegal, is driven and populated by dangerous criminals, and the women being sold are vulnerable and in danger.

I am in Phnom Penh at the beginning of my investigation into three countries: Cambodia, South Africa and Albania. All are notorious trafficking hotspots—as sending, transit and destination countries. Although I use traditional journalistic methods to gather my information—setting up interviews with experts, visiting local brothels and red light districts and speaking with prostituted women, male sex buyers and pimps—I adopt false identities in order to observe the true picture. I have to be certain that nothing I do during the course of my investigations puts the exploited women and girls in further danger.

Trafficking is a terrible problem throughout Cambodia. It is one of the favored destinations for gangs selling female flesh. There are plenty of brothels; in every town and city and many of the villages, prostitution thrives. Sex tourism is big business, and the act of paying for sex is normalized and accepted throughout Cambodian society. However, prostituted women and girls are stigmatized and punished. Of a population of 15 million, a quarter of a million are thought to be victims of trafficking in Cambodia, and it is one of the worst countries when it comes to modern slavery. Most of the victims have been trafficked into prostitution.

Nearly half the women sold for sex in Svay Pak, a poor fishing village on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, have been trafficked into prostitution. “None of them want to be there,” says my guide, Sunit. “They are abused by police as well as the men who pay for them. They can’t escape because they don’t even have any documents to prove who they are.” The traffickers bring women and girls from Vietnam and Cambodia to work in brothels and Eastern European women to serve as nightclub escorts. There also are illicit brothels from which children are sold.

During my time in Phnom Penh, my persona—for the purpose of speaking to the women in the bars (who I have been told are desperate to migrate to the West)—is that of the mother of a profoundly disabled young man who has never experienced sex. According to my story, my son Johnny had been in a serious car accident and I am his sole caregiver. I say that Johnny is desperate for a partner and I need someone to help me with caring duties.

It is a warm evening, and busy Street 172 is lined with mechanized rickshaws known as tuk-tuks, their drivers waiting for trade. The restaurants and clubs teem with locals and tourists; the bars where women are on sale are startlingly obvious. There are older white men sitting outside, many with a young local woman on their knee. It is a desperately upsetting sight.

I enter the 69 Bar with Mr. H, my fixer and security guard. Immediately, several young women rush toward us, asking Mr. H—a local man in his 30s—if he would like company. The women are under pressure to approach any customer who might buy them a drink. What the drink actually costs goes to the bar owner; the women are given a nonalcoholic mix. One of the women, with a rigid smile on her face, asks what I am doing in the bar and whether I am looking for anything in particular.

I am wearing an audio recorder so that I can recall the conversation later. I do not want to misrepresent anything that is said, and it is important that I am able to back up my claims that these women are desperate and are being exploited.

I ask if any of the bar girls in Cambodia’s sex district would be happy to marry Johnny. I feel bad about deceiving these vulnerable young women, but I’m satisfied that it will not put them in any danger to hear my story. I am in Cambodia to look underneath the veneer of the buzzing nightlife and learn about the “beer girls” who are advertised by bar owners as offering “company for lonely tourists.”

The music pounds in my ears. I am being watched closely by one of the female managers hovering around the bar. She wants to know why a middle-aged white woman is talking to “her” girls when they should be flirting with the throng of men hanging around the pole-dancing area. Perhaps she thinks I am a lesbian looking for sex with one of the young women. It is impossible for me to attach my micro camera to my thin cotton shirt without fear that I will be spotted. However, my audio recorder is already switched on, tucked firmly in the waistband of my shorts.

“I want to meet your son,” says one of the young women, all of whom speak at least some English. “I bet he is really handsome!”

“I can make your son happy, and I will marry him and come and live with him and clean and take care of him like a wife should.”

“I bet he is really handsome. Do you have a photograph of him?” asks a woman I estimate is no older than 18. “I have always wanted to live in Europe. I had a boyfriend in Switzerland once, but he left me.”

Every woman I speak to in the bars I visit offers to marry my fictional son, despite never seeing a photograph of him, and despite being told that he is so disabled he needs 24-hour care, including support with feeding and using the bathroom.

I speak to Bopha, one of the girls listening avidly to my words. “I wash and dress him and help him go to the bathroom,” I say. “I am exhausted and I need a carer for him. Johnny needs a wife. He has never known a woman sexually.”

Before I finish speaking, Bopha excitedly tells me that she will come to Europe to take care of him, marry him and do anything required to make him happy. Other women gather around and Bopha tells them that she is going to marry “a British man.”

What is so terrible about these women’s lives that they almost beg the mother of a paraplegic son to help them escape to the West to a life of unending domestic work? Put simply: the sex trade. In Cambodia, despite the glamorous sheen applied to it by academics and pro-prostitution activists, women are not “selling love” or intimacy; they are being abused and dehumanized by sex tourists and local men. In some countries, police are corrupt and violent to the women, and despite the rewriting of prostitution as “the girlfriend experience,” the public tends to despise women caught in this hellish trade.

As I leave the bar, the manager approaches and asks me for a private conversation, nodding at Mr. H, who takes the hint and crosses the street to wait for me. “If you want one of my girls, you have to ask me and Charlie,” he growls as he grips my arm. (I assume Charlie is his business partner.) “They cost me and the bar a lot of money.”

My second cover story is that of being the joint owner of a strip club in London. I want to explore how “brokering” women works in Cambodia. I have been told by European police officers stationed in Cambodia that bar and strip joint owners literally own women, and will “lend” or “sell” them to international pimps for a good price.

The White Building—once a source of civic pride—is now a run-down dwelling where prostituted women and drug addicts live alongside families. The enormous complex built in 1963 was once the pinnacle of modern housing, but it is now crumbling and facing demolition. The building, inhabited by 2,500 tenants and squatters, sits on prime Phnom Penh real estate.

I have been told to meet Malis at the nail salon in the White Building, where prostituted women congregate to share stories of violence and degradation. Now in her 40s, Malis earns her money by pimping women, although she began her involvement in the sex trade as a dancer. She is glamorous and expensively dressed. “How can I help you?” she asks, her smile false and her eyes darting around me suspiciously. “I hear you want some girls?”

I ask how I might arrange to hire two dancers to come to London and work for me. “I rent them to you; I do not sell them,” she says. “You pay me and not them. I will look after them with money, but the money you earn from them, half of it is sent to me. You keep their passports when they get to London, because otherwise they could run off with your money.”

We chat for a little longer, but I am on edge at how unfriendly, almost confrontational, she has become. “Do you have photographs of your club?” she asks. “Who are the girls that work for you? Do you have any friends who are policemen in London? How do I know who you are?” I try to answer her questions without seeming anxious, and then tell Malis that I will be in touch and give her my cellphone number. “Each girl will cost you $10,000 per year, and you pay for their flights. Can you afford this?” The idea that I could exceed $10,000 in profits per year—and pay Malis half the girls’ earnings as well as their accommodation and food—is ridiculous. I realize she is trying to decide whether I am genuine. I tell her that this is way too much and that I will be in touch if she decides to drop her price. Malis does not look at me as I leave the salon; she is already involved in another conversation by the time I close the door.

In Svay Pak, on the outskirts of the city, most people exist in dire poverty. The shantytown, whose residents are mainly undocumented Vietnamese migrants, is one of the centers of the child trafficking trade. Most commercial child sexual abuse takes place in the adult sex trade, often in legal and licensed brothels. An anti-trafficking investigator told me that all women working in the KTVs (karaoke bars that double as brothels) in the area are trafficked.

In Cambodia, three-quarters of the population live either on or below the poverty line. According to the Asian Development Bank, women earn only 27 cents for every dollar earned by a man. The poverty, the inequality of women and girls and the desensitization to sexual violence lead some parents to sell their daughters into prostitution.

I had heard about “virgin brothels” in the outskirts of the city, populated with girls as young as 10, usually sold by their families. Wealthy, powerful Cambodian and other Asian men are frequent customers. They are protected by corrupt police officers and other officials, and “virginity selling” is so endemic to Cambodian society that the virgin brothels thrive within a context of acceptance and a “blind eye” approach.

A girl is first taken to a hospital and examined by a doctor. She is given a certificate to confirm her virginity and then sold to a pimp or directly into a brothel. I make several inquiries among my contacts in the city about pimps who run the “virginity business” and am told it is much too dangerous to attempt to infiltrate this. “Unless you are Cambodian or Vietnamese, you will have no chance of finding your way to talk to the traffickers that sell virgins,” one contact told me. “Even the nastiest European pimps would run a mile from such businesses; it is way too hot.”

There is a pernicious mythology around sex with young virgins. Some older Asian men believe that sex with a child makes them more virile and brings good health. In Cambodia, there is little concept of the rights of a child, and sex with a young girl is not considered child abuse.

Unlike child sex tourism, which is frowned upon within much of society, local men who pay for sex with children are not considered pedophiles, but are merely choosing a sexual partner they find attractive.

Many “massage parlors” are fronts for brothels—it’s called “massage boom boom.” Some offer full sexual services, some oral sex or a “hand job.” Drivers who take men to these parlors know they will receive some commission. “Massage boom boom” is all over Phnom Penh’s Toul Kork district. Both Vietnamese and Cambodian girls are found at these places.

Usually a “massage” that is, in reality, a sexual act, is booked for an hour. If a room is rented for longer than that, the owner will expect more money from “his” woman. Many rooms have a one-way mirror, through which the owner can observe the activities. If the mirror is moved, the owner will know that sexual services are being exchanged without his approval.

In the karaoke bars, men can’t pay for sex on the premises, but they can take girls to guesthouses nearby. Some karaoke bars are “upmarket,” with women from China and the Philippines available to customers with lots of money. The bar owners expect a commission of about $300, which men pay to the boss, who divides it with the girl. Some girls, after being with a customer, will give him her direct number so she can cut out the boss’ commission.

Some hotels have a range of facilities (such as a night club, karaoke bar, etc.) and will also offer rooms for different lengths of time. The really good places have air conditioning. But in addition to the room rental, the owner will always expect a commission.

One evening I travel by tuk-tuk to one of the many street prostitution zones in Toul Kork. We park behind a rickety stall that by day supplies cigarettes and Coca-Cola to the many women and their pimps who hang around waiting for a sex buyer. It is 3 a.m., and the park is teeming with women. Groups of men crouch on the ground, playing cards and drinking beer. Every now and again they glance toward the women. After an hour, I see one of the men walking toward two women standing together. He raises his voice, shouts and shakes his fist. My fixer tells me he is telling the women they had better bring him more money before daylight or he will “beat them hard.” I notice the women are wearing black masks, and I wonder if this is to protect their identity, with prostitution being both shameful and punishable by law. My fixer shakes his head: “No, this is so that the men can see they are prostitutes. It means they [the johns] don’t get into trouble if they approach a nice girl.”

Cape Town, South Africa

Today, one quarter of a million people live in modern slavery in South Africa, a shocking statistic for a country that abolished the apartheid system in 1994.

In the Milnerton suburb of Cape Town, sexual exploitation is rife. Long Street is home to some of the finest bars and clubs Cape Town has to offer, but what many people don’t know is that it is also a hotbed of drug dealers, thieves, con artists and women in prostitution. On Aug. 14, 2017, I set out to interview prostituted women in Cape Town.

I meet Grizelda Grootboom at the offices of Embrace Dignity, a sex-trade abolitionist organization in Cape Town. She was just 18 when she was trafficked into prostitution, betrayed by someone she considered a friend.

Growing up in an orphanage, Grootboom’s best friend was a girl named Leah. But Leah was raped and stoned to death, an incident that traumatized Grootboom, who soon turned to drugs. On her 18th birthday, Grootboom was told she had to leave the orphanage because she was now considered old enough to take care of herself. With no one to turn to, she contacted a drug-using friend who had moved to Johannesburg to study.

“My friend said that she would get me work and help me start afresh, so I took the train to Johannesburg, and my friend met me and was full of promises,” Grootboom says. “She took me in and protected me from the gangs on the streets. She took me to a room and said that she’d get me food, but that was the last time I saw her. That very same night, I was beaten badly because I refused to have sex with one of the men that came to buy me.”

Over a period of 12 years, Grootboom was trafficked within South Africa, facing violence from police officers as well as johns. One night, she was gang-raped and became pregnant. Later, while she slept in a brothel, a pimp drugged her and attempted to abort the fetus from her womb. Grootboom was hospitalized as a result, and after her release she moved between homeless shelters.

It took awhile for Grootboom to get out of prostitution, and only when she discovered Embrace Dignity did she begin to recover from her ordeal. Nine years later, she supports other victims of trafficking; last year she was invited to speak at the United Nations about the horrors of the sex trade.

“I would have loved to have become a dancer, or a singer,” Grootboom tells me when we meet for dinner. “Everything was stolen from me: my dreams, my dignity and, in some ways, my soul. But I refused to let them destroy me, and I know now that I am strong, and that I can help some of the girls avoid the horror that I was put through.”

I ask why she thinks no one protected her during her time as a prostitute. “The men who buy and sell us tell lies,” she says. “They say we like what we do, and that we are choosing to do this. As if any woman or girl would choose to be sold. People in South Africa need to face the truth. Prostitution is slavery. Now that I am out, I will focus on my future, not the past. I want the girls to have a better future.”

From talking to Grootboom and others at Embrace Dignity, I learned quite a bit about the sex trade in Cape Town. One of the women says police routinely ignore the existence of brothels, even those with very young women who may be trafficked.

Sexual violence toward women and girls is rife across South Africa. Every eight hours, a woman is killed by a male partner somewhere in the country, and one woman in five has suffered rape or sexual assault at least once. In some provinces, more than 75 percent of women have experienced male violence. Among prostituted women, estimates of HIV rates across the country range between 39 percent and 71 percent.

At a Cape Town braai—a traditional barbeque restaurant—I am introduced to Vicky, who says that women involved in street prostitution “do good business” in the premises. I ask whether the women have pimps; she says that without them, the women would be exposed to too much danger. “Are the pimps violent?” I ask. “Yes, but at least she will know him and be used to him when some of the customers get out of control.”

In 2017, Cape Town police arrested five people on charges of human trafficking, prostitution and extortion. “Operation Madame” alleged that Shantel Bridger was the ringleader. Bridger is now awaiting trial, along with her co-defendants, facing allegations that she ensured the trafficking victims were addicted to drugs and used violence to keep them in check. At least two underage girls were found on the premises. Police believe the gang could have pocketed more than $2.5 million by blackmailing sex buyers between 2012 and 2015.

Patric Solomons, director of the Cape Town child rights group Molo Songololo, tells me that child sexual exploitation is rife in the city. “There is the system where ordinary persons, young men in their late teens or early 20s, get together on the weekends and they have sex parties. Their job is to procure girls for that weekend,” Solomons says. “So the notion of a child or a person being held or kept in a brothel and then being prostituted and then being moved to another brothel happens far and few between; rather, they are taken to the homes of men who wish to abuse them.”

I am advised by a police contact that the Milnerton Flea Market is one of the places, along with the Greenmarket Square, where traffickers broker deals. I go to Milnerton early on a Sunday morning, accompanied by a local fixer—a young man who had previously been involved in low-level criminal activity. “The Nigerian traffickers come here and put a price on the girls,” he told me. “I heard that they sometimes have auctions at night, where they can see how pretty they are and how much they sell them for.”

Albania

The main street-prostitution zone in Tirana, Albania’s capital, is at the back of the National Museum of History. I am told to meet a man known as RT outside the primary entrance. I was led to RT by a bar owner I contacted while claiming to look for “girls to persuade back to London to work in my lapdance club.”

RT looks like a stereotype of an Eastern European pimp. He is wearing a heavy, black leather jacket despite the warm evening, his long black hair is pulled into a ponytail, and he is carrying two mobile phones.

RT introduces me to Adrian, the owner of a nightclub that offers sexual services to customers. I am told that the women apply for jobs in the club via Facebook advertisements. I meet Vera, a 21-year-old woman in the notorious Blloku district, known for its lapdance clubs and massage parlors.

Vera was trafficked throughout Tirana and the towns of Durres, Vlora and Saranda. “I was sent to work in the Lizard Club in Blloku,” she tells me. “But I hate it.”

“All of the prostitutes here have pimps,” Vera says. “They usually are their boyfriends, sometimes even their older brothers. But they get more by selling us into clubs to the bar owners, and there we have to do what they tell us. We can’t really get away from the clubs, because the men who sell us to the clubs watch us at home, and the club owners watch us at work, so there is nothing we can do.”

In the Shqiponja club, notorious for prostitution, I use my cover story: I am a 55-year-old lesbian who has never dared to have a sexual encounter with another woman. “I would like to spend some time with one of your ladies,” I tell the bartender. He is a jovial man who masks his shock almost immediately. “I know it is unusual, but I am attracted to women and find it difficult to meet them otherwise.”

“There are girls available for everyone,” the bartender says. “I can get you a group if you want, or just one girl. As long as you can pay, you can have a girl.”

One of the women working at the bar walks unsteadily towards me; she appears to have been drinking. She shouts at the bartender, but I don’t know what she is saying. Another woman joins in, and an argument ensues. The atmosphere has turned toxic, and I indicate that I will be back soon and leave the club.

I travel to Vlora, a coastal town at the southern end of the Adriatic Sea, to visit the Vatra Psycho-Social Centre, an anti-trafficking nongovernmental organization that provides support to women and girls who have been trafficked into the sex trade.

I have been told by police officers and heads of charities that the war against sex trafficking is being won in Albania. But the interviews I conduct with other officials tell me something different.

Balida, I am told by my fixer, is an anti-trafficking expert based in the police station in Vlora, which has a terrible problem with trafficking and prostitution. At one stage, almost every job in the town was somehow related to the trafficking of women and girls to the coast of Albania. Whether it was in the production of speedboats, which transported women to Brindisi, Italy, the running of hotels that harbored girls and women during the trafficking process, or the provision of security or money-laundering services for criminal gangs, in many ways the economy was boosted—at least for the criminal gangs and entrepreneurs—by the buying and selling of women.

“The girls are prostitutes, and even if they are trafficked, they don’t help themselves, because they will never make statements about the pimps,” Balida says when we meet in a cafe near the police station.

“We can’t stop these cases from happening—the girls are doing it for the money. To them it is just prostitution.”

It seems incredible that a so-called trafficking expert from the police takes such a cavalier view of the women and doesn’t appear particularly interested in arresting those doing the trafficking.

Although some academics argue that for Albanian women escaping hardship and poverty, sex work is far preferable to factory work, the lives of the women trafficked out of the country are anything but improved. On their return to Albania, having been trafficked to countries such as Italy, Belgium and the U.K., many women tell horrendous stories about their experiences in brothels. Some women, such as Silvana Beqiraj, do not even live to tell the tale.

After Beqiraj, from rural Albania, was found dead in a canal in France in 2014, I traveled to her home village to investigate. Beqiraj left the impoverished village of Ndërmenas in the district of Fier in 2011, telling her parents she was going to Montpellier to work as a cleaner. Three years later, her naked body was found floating in a canal. My fixer, a local journalist, tells me that the family denies the notion that Beqiraj may have been trafficked, and that they are leery of outsiders asking questions that might suggest this.

On the way to Fier, I am told there is heavy drug use in the surrounding villages, and that some young men are pimping local women to pay for heroin and crack cocaine.

I arrive at the Beqirajs’ farm around midday, and walk past chickens pecking the dirt along the uneven track to the ramshackle house. The family is clearly poor; my fixer tells me that the father drives a taxi to supplement the meager income derived from the farm.

Beqiraj’s mother, Yllka, her eyes filling with tears, greets me at the door, wiping her hands on her apron. Without hesitation, she tells me about her daughter’s death, and how she has not slept well since. Yllka goes to an old-fashioned sideboard in the corner of the kitchen and takes out a large folder. “Here is her passport, and her death certificate, and all the other papers,” she sobs. “Can you do something to help us?”

Mehmet, Yllka’s husband, his face lined with grief, enters the kitchen. The family had phoned him while he was in his taxi to tell him about the visitors asking about his daughter. The sun is beating on the corrugated roof, and Yllka pours everyone a cold drink. Mehmet nods his head and says, without preamble, that he and his wife have been treated “very badly” by both the French and Albanian authorities, and there are “no answers” to the question as to what happened to Beqiraj.

Dritan, Beqiraj’s brother, is sitting at the kitchen table, not speaking except for the odd grunt of “yes” or “no” when I ask him questions about his sister’s case. Dritan is depressed, according to his mother. “Lots of his friends take the girls from the village and have become pimps. He knows who took Silvana,” she says. We walk to Beqiraj’s grave, on a dry patch of land above the farm. Mehmet leads the way. “It is tradition,” he tells me, “for men to go first.”

Both Yllka and Mehmet deny that Beqiraj was trafficked to France, preferring to believe that she was in prostitution “voluntarily.” Police investigations into her death, both in Albania and in France, have not uncovered any clues as to who killed her.

Other than the family, no one will speak to me about Beqiraj, but when I visit the neighboring village, all the men in a bar that serves as a kind of community center told me that it is “well-known” that Beqiraj’s village harbors a number of entrepreneurial traffickers, and that they regularly broker deals with large criminal gangs that procure girls and women and introduce them to men from the syndicates.

In rural Albania, women and girls have little or no status, and Kanun law, very similar to sharia, is practiced. Kanun is a deeply conservative viewpoint that places the “honor” of the female very high up. It is forbidden for women and girls to be alone with men who are not their immediate relative.They do not eat or socialize with male members of the family. It is common for girls to be sold into marriage—often polygamous marriages—as young as 13 or 14.

Under Kanun law, a woman is deemed to be worth half as much as a man. But on the open market, when sold into prostitution, she is worth rather more.

Back in Vlora, I meet Valmira, a nervous young woman who wrings her hands constantly and pulls imaginary threads from her clothes. When her father died, Valmira was expected to leave school just before her 13th birthday and get a job in a factory. “I did not have a very beautiful childhood,” she told me. “When my father died, my mother told me that I was not her daughter but that my father had brought me home from somewhere else.”

The tension in the house grew until her Valmira’s mother threw her out of the house. Valmira traveled to Vlora to stay with her sister and brother-in-law. “I stayed here six months, then I left because the husband of my sister started with sexual harassment. I couldn’t endure such a situation so I returned back home and began sleeping outside on the balcony. Then I made the acquaintance of a man who worked with my cousin. I was 14 and he was 23 years old.”

When Valmira brought the man home to introduce him to her mother, there was a huge argument because the man was Roma. To prevent her daughter from marrying him, her mother arranged for Valmira to marry a man she had never met. “I ran away,” Valmira says, sobbing. “I could not bear to marry this stranger, and I loved my boyfriend, but it turns out I made a huge mistake.”

The man Valmira loved turned out to be a trafficker. He took her to a rented apartment and locked her in. There was no furniture, no heating and very little food. She shouted at the window for her neighbor. Soon, somebody came to the window and told her, “You’re not the first that he brings here. You should go, because he’s deceiving you. ”The neighbor gave her information about the shelters she could go to.

Valmira escaped when the trafficker left the door unlocked. She found her way to Vatra, where she stayed for 18 months. In Vatra, Valmira made friends with a girl named Anna, whom she stayed in touch with after they both left the shelter. “When I learned that she was going to Greece, she told me that if I wanted to work I could come with her and we can both work as cleaning ladies,” Valmira says.

Anna took Valmira to Kalithair, near Athens. “Until we arrived at the house, I really did think that we were going to be cleaners,” she recalls. “Then Anna disappeared and some men came. I think they were Romanian. It was then that I realized Anna had taken my passport and given it to the men. They owned me now; they had my papers and I knew I couldn’t escape. I could not believe that this had happened to me again.”

There were several other women from Albania in the house, and Valmira realized that Anna was a recruiter for criminal gangs: “She sold me. She traded me in for money for herself. This is terrible that a woman could do this to another woman.”

Valmira was locked in a basement and allowed to come up to the sitting room only to meet johns. There were cameras in every corner of the room. The women were permitted to wear only underwear when they met the men who came to buy them. “I wanted to escape,” Valmira says, “but I could not because there were these Romanian guys outside the front door like bodyguards.”

During the month Valmira was kept at the house, she was forced to have sex with up to 10 men a day. She did not even think about trying to escape this time—she had seen how the women who had tried to get out were punished, as were those who refused sex or particular services with the johns.“The punishments the pimps gave the girls who didn’t obey them terrified me,” Valmira says. “They would batter them with fists and kick them. They used small knives on them.”

One thing Valmira witnessed, after four weeks of being held captive, will haunt her to her dying day, she says. Valmira saw pimps murder one of the women in full view of the others. “They killed the girl with small knives and left her body there, not taking her to the hospital. They took their time doing it,” Valmira says. “They made her bleed to death and tortured her. We were made to watch, and all the time the girl was screaming and the pimps laughing, telling us that the same would happen to us if ever we tried to leave.”

As far as Valmira was concerned, the pimp’s plan backfired. “I knew I had to get out of there and was prepared to risk being killed to at least try. It was beyond hell what was happening, so I took a chance.”

A local Greek woman, who was not part of the gang, was recruited to the house to translate for some of the johns and other pimps wishing to make deals. Valmira befriended the woman and, when she was sure she could be trusted, told her everything that had happened in the house. “I saw she was a good person,” Valmira says, “so eventually I told her everything. I told her about the dead girl, the beatings, the rapes and how we had our passports taken away. I described some of the men who paid for sex with us, and what they did and how it was like torture. She cried when I told her, and she promised to help me.”

Several weeks later, as the Greek woman distracted the security guards, Valmira escaped. She went straight to the police station in a nearby town and reported the murder, as well as what had happened to her and the other women in the brothel, but she was dismissed. “I returned to Vlora and to the shelter,” Valmira says, “and have asked the police so many times to investigate the murder and the trafficking gang, but they say I was lying—that I was just a voluntary prostitute.”

In Cambodia, South Africa and Albania, I found that trafficking into prostitution is a viable way for exploiters to earn a living. In all three countries, sexual violence toward women and girls, poverty and extreme male dominance has created a context in which the men who pay for sex are not stigmatized, but the women and girls sold are seen as spoiled goods.

Men from both the U.S. and the U.K. regularly travel to these countries as sex tourists and pay to have sex with the most vulnerable and marginalized women and girls. The presence in all three countries of international aid agencies, charities and nongovernmental organizations that are supposedly working toward developing democracy and better civil society infrastructures appear to do relatively little to tackle the problem of sex trafficking. Indeed, as we have heard over the last few months, organizations such as Oxfam exacerbate the problem. Until paying for sex under any circumstance is stigmatized and criminalized and women and girls are helped to escape the sex trade, trafficking will continue to flourish, and abusers will act with impunity.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.