The 1942 Internment of Japanese-Americans Holds Lessons for Today

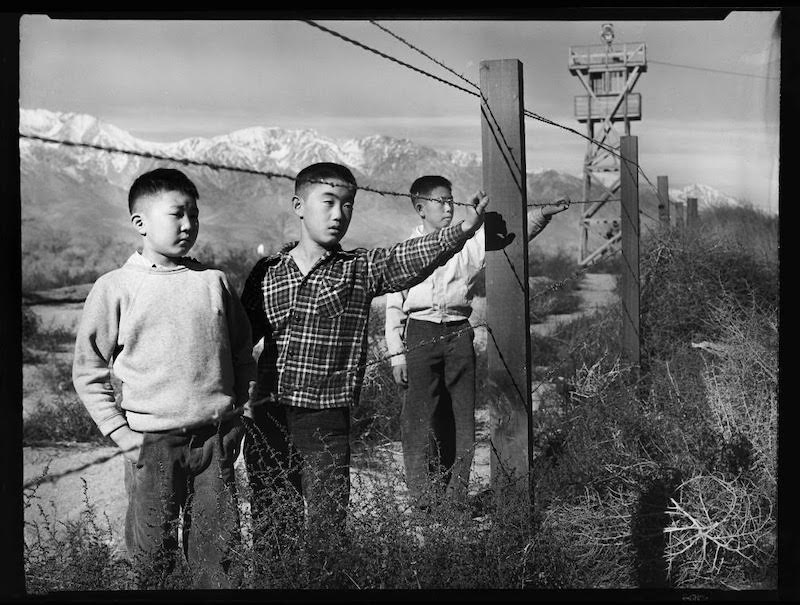

"Then They Came For Me," a traveling exhibit, reminds viewers how easily history can repeat itself. Japanese-American children reach the outer bounds of a California internment camp during World War II. (Image courtesy of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation)

Japanese-American children reach the outer bounds of a California internment camp during World War II. (Image courtesy of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation)

Photo Essay

photo essay

Photo Essay

photo essay

With detention camps along the U.S. southern border and the president’s revised Muslim ban upheld by the Supreme Court, Karen Korematsu thinks it’s important for people to know the history of 120,000 Japanese-Americans, two thirds of them native-born citizens, who were incarcerated during World War II without due process. Korematsu, director of the Fred Korematsu Foundation, a civil rights educational organization, travels the country to talk to students about her father, Fred Korematsu, who refused to go to the camps. His case went to the Supreme Court, which ruled against him and upheld the government’s internment order in a 6-3 vote.

Korematsu wants people to know how Japanese-Americans were treated after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. She hopes that by teaching history, a similar fate for others can be prevented.

Korematsu was an adviser for an exhibit titled “Then They Came For Me.” Currently on display in San Francisco until the end of May, the exhibit next moves to Chicago and New York. It features photos of the internment camps, including some by Dorothea Lange, work by incarcerated Japanese-American artists and historical documents. The exhibit includes such artifacts as Fred Korematsu’s letter thanking his American Civil Liberties Union attorney for taking his case; trunks the prisoners took to the camps; and a jacket given to a man sent to a prison camp marked with “E.A.,” for “Enemy Alien.”

Such artifacts make the internment real to people, says Korematsu, who talked with Truthdig writer Emily Wilson about how Japanese-Americans were temporarily housed in horse stalls, the parallels between what’s happening now and what happened in 1942, and why Japanese-Americans rarely talked about the internment.

Emily Wilson: What reactions are you getting to the exhibit?

Karen Korematsu: People really hadn’t seen one like it before. Many of the photographs were blown up to give them more impact. Somebody commented to me about a photo of a young boy peeking out through the suitcases. Many people didn’t realize that children and babies were also put in prison camp, as well as the elderly and the infirm. Even if you were in a hospital, they pulled you out and put you in a prison camp. That’s inhumane. It’s appalling to see that age range, from baby to elder, and people need to see this to see the inhumanity and the violation of human rights of mostly Americans without due process of law.

Also, it brings relevancy, with the artifacts—like the trunks people had and information about my father’s case, and asking “What would you have done?” As I crisscross this country, people ask me, “Why didn’t they protest?” Well, they were put in prison, and there was no time. You could have refused, like my father, but that was a federal offense, and people were just plain scared. Especially people like my grandparents, who were stateless—they were born in Japan. I think of my grandmother, who had worked very hard raising four boys, and they hear the Imperial Army of Japan has bombed Pearl Harbor, and then they’re told, “You can only take what you can carry in your two hands, and the rest you have to leave behind, and you only have 48 hours.” You could try to sell, maybe 10 cents on the dollar, or try and give things to a friend or neighbor, but in some cases, people didn’t think the Japanese were coming back, because they were gone three or four years.

EW: What are the parallels you see now with the detention centers on the border and the Muslim ban?

KK: The most appalling factor to those camps along the border is the separation of families. They did that in 1942—they separated families. The day after Pearl Harbor, the FBI rounds up over 2,000 people of Japanese ancestry and takes them to Department of Justice camps, and their families don’t even know what’s happened to them. After 9/11, in 2001, they did the same thing to Muslims—the government rounded up people and put them in Department of Justice prisons, and their families didn’t know where they went. That was 2001, and here we are doing same thing in 2019, where they’ve separated families and the parents don’t know where the children are.

This is why this is so important, because we need to learn the lessons of history so that we stop repeating history.

EW: How have you seen Japanese-Americans get involved?

KK: The day after 9/11, my father was one of first people to speak up, because his Supreme Court case was cited as a possible reason to round up Muslim Americans and put them in concentration camps. The Japanese American Citizens League said, “No, you cannot do this. This is what you did to us in 1942.” So at least now what we have is other civil rights organizations that can speak up. In 1942, there were not the organizations to do that.

EW: What about with the Muslim ban?

KK: On Jan. 27, 2017, was President Trump’s first executive order. That was the Muslim ban. That was 1.0. Then, because there was so much pushback, especially by the Japanese-American community, it became 2.0—the immigration ban. Then there was pushback there. So the government waters down the impact with the euphemisms, then the immigration ban became 3.0—the travel ban, and [it] included Venezuela, just to kind of say, “This is not about Muslims.” The day after the first Muslim ban, Japanese-American started speaking up, to say, “This is wrong,” and that’s when everybody went to the airport. It would have been so heartwarming for my father to see all these attorneys holding signs—some of them were real estate attorneys, but they wanted to help you. That was so great. Finally we had all these people come together who wanted to help others because they were being targeted and their civil rights were being violated. My father’s favorite audience to speak to was attorneys, because he knew they would have the tools to help fight any injustice, and that was a perfect example.

EW: You didn’t hear about your father till you were in high school and a friend mentioned him in a report she was doing. Why didn’t people talk about the camps?

KK: The Japanese-American community at large didn’t talk about the incarceration. You have to understand that Japanese-Americans are put into prison camps without due process of law. They are stripped of their dignity and treated like animals—they were first put into horse stalls. As my father said, horse stalls are for horses, not for people. They didn’t have their own food, and they were stripped of their possessions. The inhumanity was so appalling. I think about my grandmother, this lovely, dignified woman who came from Japan and looked at America as the land of opportunity and was excited to be here, but she had to endure all that. In the lavatories, there was no privacy—there were open latrines, there were no partitions, the showers were all communal. Can you imagine? When the war was over and the camps were closed, all that was given to these people was $25 and a bus ticket, and that was it. And they were supposed to start over from that. So they went to churches and Buddhist temples, and families lived together and tried to support each other. All the Japanese-Americans wanted to do was to get on with their lives and to prove they were good Americans citizens or [that] they loved this country. They left Japan because they believed in this country. How do you tell your family that you were stripped of your dignity and possessions and had to endure these inhumane conditions? That’s not something you share with your family, especially your grandchildren. How do you explain that—that our own government treated American citizens this way?

EW: Is there anything that makes you hopeful?

KK: When I talk to students, they give me hope. My father gave me this charge of education five months before he passed away. I don’t know if I’ll see peace in my lifetime, but I’m hoping [that] through [the students], we make change in the way that we treat people.

Students are very interested when I talk to them about it. I use my father’s story as a springboard to launch the other information. I start from a personal perspective of how I learned of my father’s Supreme Court case as a junior in high school from a friend giving a report. Personal stories are what resonate with these young people. I tell them in elementary school that around December 7, the teacher would talk about the bombing of Pearl Harbor and say that “the Japanese are very bad people and they bombed Pearl Harbor and killed 2,000 Americans.” Then the students would blame me and bully me and say, “Go back to Japan—you don’t belong here.” It happened to my brother, who’s four years younger, too. I tell students I’m bound and determined to change that, and Fred Korematsu’s story is about one man who made a difference, and so can they.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.