The Restless Radicalism of ‘Planet of the Apes’

Wes Ball’s reboot continues a 60-year tradition of slyly shape-shifting critiques by Hollywood’s longest-running sci-fi series. Graphic by Truthdig. Images courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Graphic by Truthdig. Images courtesy of 20th Century Studios

The new Wes Ball-directed “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes” marks the return of one of Hollywood’s longest running franchises. It’s the 10th film in a series that has run the gamut from low-budget exploitation flick to major studio blockbuster. Throughout its nearly 60-year history, it has often been politically incendiary and always worn its bleeding heart on its sleeve.

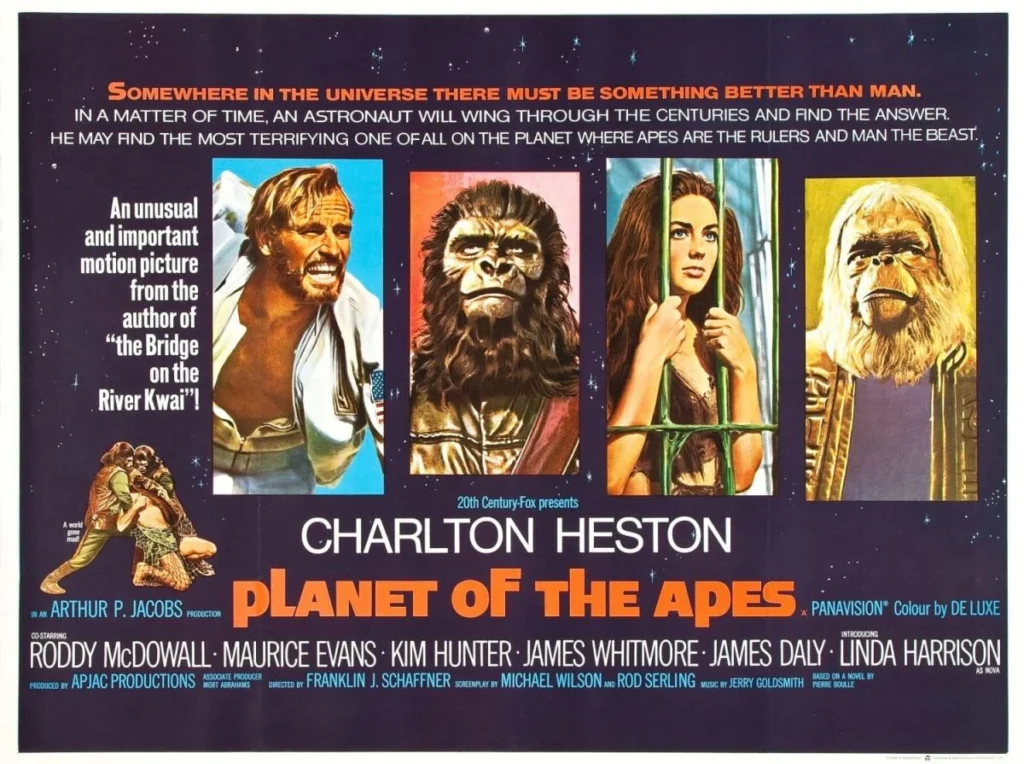

Based on Pierre Boulle’s 1963 French novel “La Planète des singes,” the story was adapted to the big-screen five years later with the Charlton Heston-led “Planet of the Apes.” The 20th Century-Fox release was a smash hit, netting $33 million on a $6 million budget and launching a genre staple that would be parodied, copied and rebooted to the current breaking point. Indeed, the new “Kingdom” marks the third time the series has been relaunched since 2001. The original run of five films, released between ’68 and ’73, used a number of pulpy, lo-fi cinematicstyles to tell a continuous story anchored by the core “Apes” idea of refracting human experience through an inversion of primate evolution.

The original “Planet of the Apes,” directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, followed a trio of American astronauts (led by Heston’s Taylor) who arrive on an alien planet to find the human-ape power structure flipped. As in Boulle’s novel, this society is run by a cast of intelligent, verbose apes: liberal chimpanzee scientists, conservative orangutan politicians and militaristic gorillas. Human beings, meanwhile, are mute, held in cages and experimented upon. At its core, this premise echoed the modern mistreatment of animals for science and industry, a potent theme that would resonate throughout future iterations of the series, but the first movie is often remembered for its gut-punch of an ending. Written by Rod Sterling, the original “Apes” features a “Twilight Zone”-esque twist that departs from the novel: the now iconic beachside reveals that the titular planet is a future Earth in which humans long ago laid waste to civilization in a global thermonuclear war.

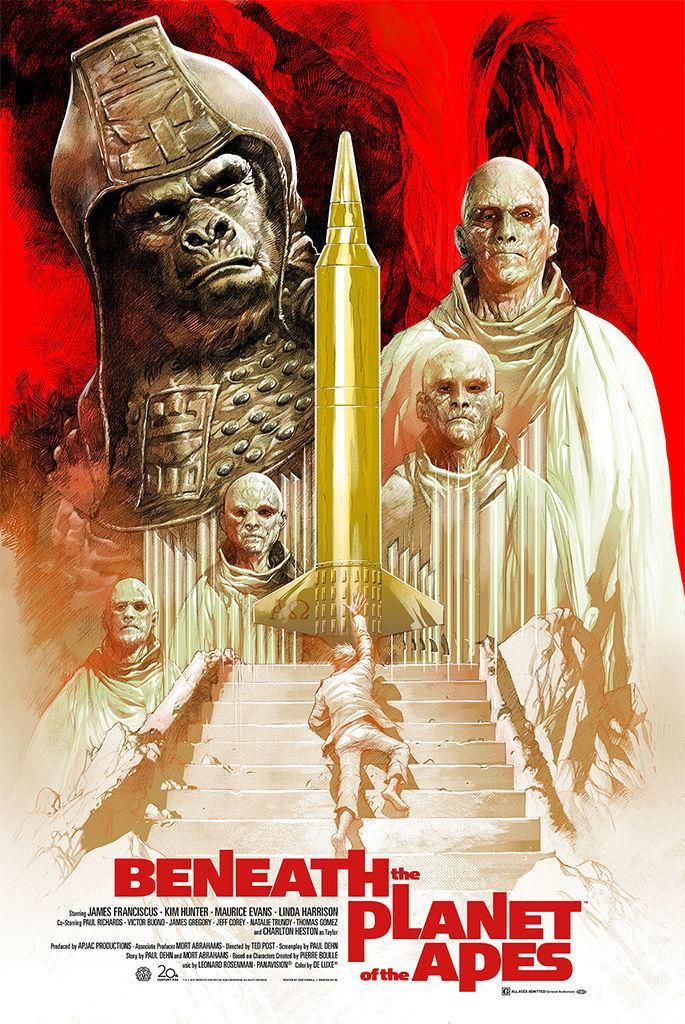

This nuclear theme was then continued in the 1970 sequel (Ted Post’s “Beneath the Planet of the Apes”) in which apes and the human astronauts discover a community of human survivors deep underground, transformed by radiation into mutant psychics. In a macabre twist, they worship a nuclear warhead that is detonated in the final scene, once again proving humanity’s essential warlike nature (and that of primates, albeit as a reflection of our own).

The sequel also depicts placard-wielding chimpanzees protesting the oncoming war between the species, a pointed reference to America’s then ongoing anti-Vietnam war movement. The image of pacifist chimps performing sit-ins may be silly by design, but it served as an appropriate bridge to the series’ comedic third entry, Don Taylor’s “Escape from the Planet of the Apes.” Set in then-contemporary 1970s L.A., “Escape” follows three chimpanzees who escaped Earth just as it exploded and, through the same temporal disturbance that propelled Heston’s Taylor forward several millennia, traveled back in time for a comedic fish-out-of-water romp without the burden of science fiction sets and costumes. The film is mostly light in tone until its own bleak ending — a series staple by this point — which sees the charming ape survivors shot dead for fears they might one day take over. Planting the seed for the next installment, they notably leave behind a child ape that cries out for its mother — in spoken words — as the movie fades to black.

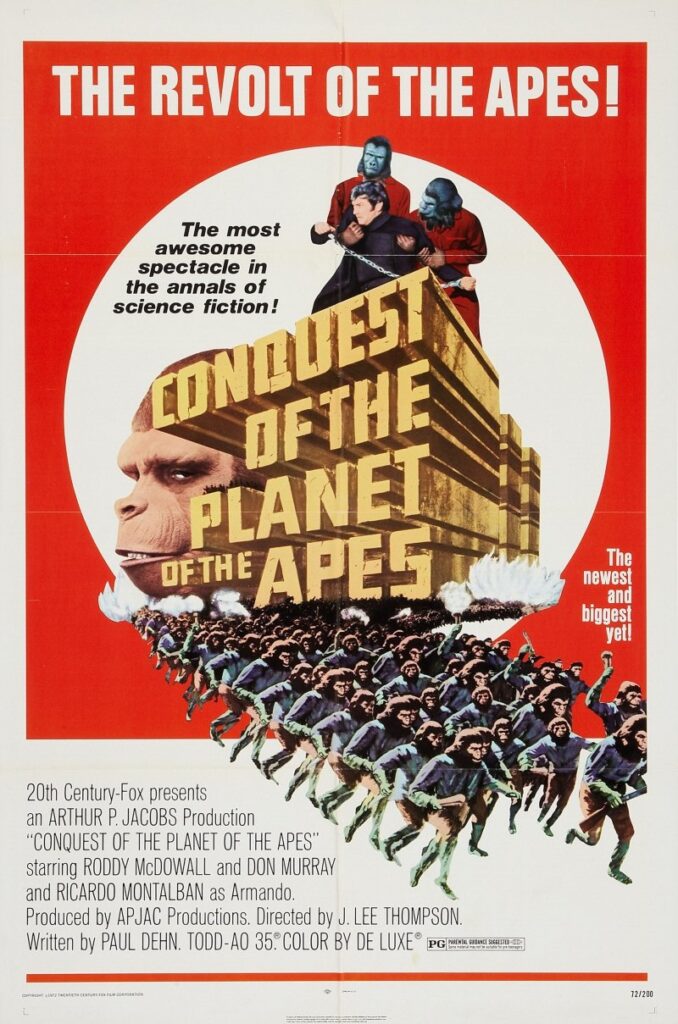

J. Lee Thompson’s cheaply shot follow-up, “Conquest of the Planet of the Apes,” took the series in the radical direction that continues to retain the allegiance of the “Ape” franchise. Shot for a mere $1.7 million in the brutalist compound of L.A.’s Century City, and using noticeably flimsy ape masks, it jumps forward to the dystopian year of 1991 predicted in the previous film. All cats and dogs have been wiped out by disease; to replace them, human beings keep apes as pets and slaves, trained to be docile. This relationship introduces direct critiques of capitalism into the franchise, laying bare not only the inhumane heart of a tiered system that extracts labor from a vulnerable proletariat — primate or otherwise — but one that cuts corners to the point of cruelty. The enslaved apes are undoubtedly oppressed in this scenario, but human workers can also be seen protesting their replacement as a money-saving initiative.

The surviving intelligent ape child from the previous film, now a sheltered youth named Caesar, is inadvertently caught up in this system and begins planning a mass revolt. Essentially a Marxist revolutionary, Caesar is the focal point for the series’ political musings, which are now rife with blatant callbacks to chattel slavery; the film’s most striking images involve legions of apes being led away in chains.

The specter of race always hovered in the series’ background, whether through the apes’ own caste system, or the movies’ notions of bigotry and exploitation. But “Conquest” yanks it to the fore. MacDonald (Hari Rhodes) is the series’ first notable Black character, whose perspective on the slave revolution becomes pivotal. Despite his position in government, white characters snark about his seeming affinity for apes (that is, his refusal to engage in sadistic cruelty) while Caesar expects him, more than the movie’s white villains, to understand and sympathize with his revolt, given his lineage. By drawing out the series’ central metaphor in this way, and making the parallels between the apes and Black Americans overt, the film steps into unwieldy, uncomfortable territory, given the sordid real-world history of invoking ape-like comparisons to demonize and dehumanize Blackness.

The film climaxes in a fiery act of rebellion and a speech from Caesar about apes overthrowing their masters. But studio mandated reshoots resulted in Caesar showing mercy towards his captors in a manner totally incongruous with the character and story. This re-tooled ending, aimed at a more favorable MPAA rating, fundamentally changes the movie’s emotional arc by robbing it of catharsis and sanding down the revolutionary politics that could have made for a radical pulp sci-fi fable.

Thompson went on to helm the fifth and final film in the series, 1973’s similarly inexpensive “Battle for the Planet of the Apes,” another entry whose politics feel compromised. By this point, interest in the series had declined — “Conquest” had pulled in a mere $9.7 million at the box office — and a combination of rushed production and a reduced $1.7 million budget led to troubles behind the scenes. Thus far, all the sequels in the series had been penned by Paul Dehn, who was unavailable for “Battle,” leading to the hiring of “The Omega Man” screenwriters John William Corrington and Joyce Hooper Corrington — who, by their own admission, had never seen any of the previous “Apes” movies. Notably, filming on “Battle” also began without a completed script in place; a recipe for disaster.

Several years after “Conquest,” apes and humans live in relative harmony. When a war eventually breaks out — one that seldom feels threatening, thanks to the movie’s meager budget — it’s largely fought between violent factions who are in the minority. The apes treat the word “No” as a reclaimed slur from their slave days, but this is the only echo of real-world racial politics in the movie. Its ending, set several centuries in the future, hints at potentially lasting peace between the species, another sharp departure from the series’ desolate tone and introspective spirit.

After a hastily-canceled TV show in 1974, and its short-lived animated follow-up in 1975 — both were flimsily produced sequels to, and pseudo retellings of, the 1968 original — the franchise lay dormant until Tim Burton’s long-in-the-works 2001 remake. Burton’s film gestures towards race by featuring slave-driving apes and wealthy political elites who use language reminiscent of the antebellum south. But despite these many allusions, the story itself isn’t really about race or oppression. Its primary concern is the power of advanced technology, which, in a flip-side to its predecessors, the movie valorizes. Mark Wahlberg’s protagonist Leo uses his stranded spaceship to defeat legions of warring apes; when Leo’s chimpanzee companion arrives via an escape ship, they fall to their knees, in the mistaken belief that this is the Christ-like return of one of their prophets. The point may be depicting the shackles of religion, but it feels like a fundamental betrayal of the original movies, since the primates all but bow at the feet of human ingenuity, believing it akin to magic. Burton’s “Apes” doesn’t confront power, it worships it.

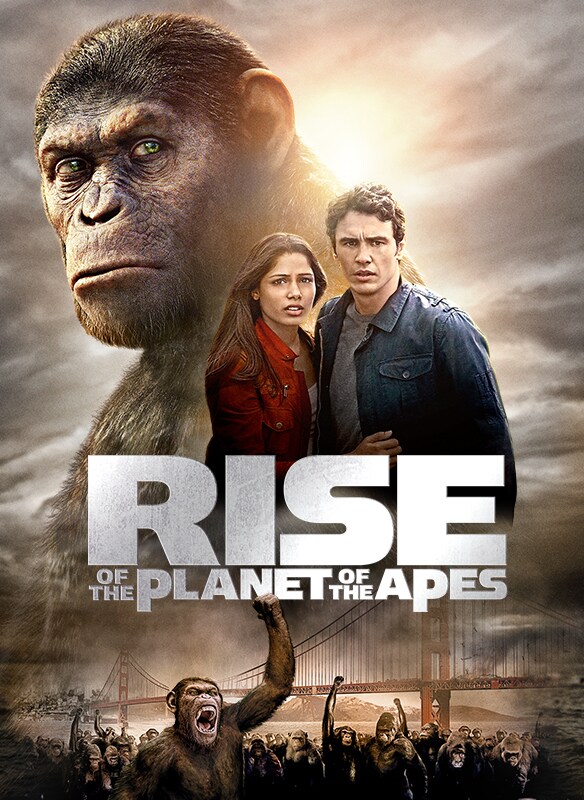

This was corrected when the series relaunched a decade later with updated performance-capture technology and another ape named Caesar, this time played by Andy Serkis. Where the films once wrestled with the destructive nature of humans and primates as an essential folly, Rupert Wyatt’s “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” (2011) kicks off a new trilogy whose politically charged approach isn’t just about these intrinsic qualities, but the human-made structures that permit them, and the specific scenarios that enhance them.

Consider the fear of disease. At the end of “Rise,” it is a pathogen, rather than nuclear war, that wipes out most humans. In subsequent entries, those that remain turn to violence and paranoia for survival — humans and apes are constantly suspicious of one another, and remain at the precipice of armed conflict — portending the political divisions that would eventually erupt during COVID-19. Similarly, “Rise’s” statement about the ethics of animal-testing is not meant to be inferred (as in the original “Planet of the Apes”), but is a central premise. Rather than a circus, this version of Caesar is born in a pharmaceutical testing lab.

Where guns were once incidental to the “Apes” movies, the new trilogy’s second installment, Matt Reeves’s “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes,”” is driven entirely by the escalation of weapons stockpiling. Social fear and suspicion create the conditions for inciting incidents that shape the plot and characters. Just as “Rise” reflected the experience of SARS and H1N1, “Dawn” reflects the anxieties of a post-Columbine society reeling from never-ending gun massacres and deadlocked firearm debates.

Reeves’s “War for Planet of the Apes,” which concludes the reboot trilogy, is arguably the most provocative installment of the entire “Apes” franchise. In it, the surviving apes are hunted down by a rogue faction of a dwindling U.S. army who resemble the underground mutants in “Beneath” in their worship of power. Where the mutants branded “Alpha” and “Omega” insignia on their revered nuclear warhead, these soldiers brand these marks on ape flesh and American flags as they beat defenseless simians to the tune of the U.S. national anthem — a bleak vision of American military might in the era of the “forever wars.” The film’s critique also evokes the eugenicist undertones of militarism and empire: the villainous American soldiers are on a mission to wipe out any humans infected with a virus that makes people mute.

Over the decades, the series has swung between human and ape perspectives, from humans trapped in a surrealist simian nightmare, to futuristic apes welcomed (and eventually enslaved) in modern America, and to modern apes gradually imbued with intellect. Ball’s “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes,” which opens this week, is set centuries after the recent trilogy, and returns the apes to the top of the food chain. But it also tells its story from a thus-far unfamiliar vantage: that of the apes in power.

The story introduces a new cast of characters led by the sheltered adolescent Noa (Owen Teague). Noa wrestles between two competing visions of ape society based on Caesar’s story, which by now has now passed into legend. The creators of “Kingdom” not only recognize the Biblical parallels in “War” — in which Caesar, a Moses-like figure, rescues his enslaved tribe and leads them to a promised land — but incorporate these parallels into their text, as dogma passed down over generations. Some peaceful apes cling to Caesar’s teachings to promote intellectual inquiry. Others contort his revolutionary tale to sow distrust and oppress not only their fellow apes, but also the rump, mute and feral human population.

Its notions of myth as cultural building block, and religion as primal power structure, fulfill the promise of Burton’s mismanaged remake. The sequel, through plot developments best left unspoiled, is appropriately suspicious of technology and its misuse, and ends on a note that raises questions about the human-ape dynamic and the costs of progress.

Despite its growing pains as a franchise kick-starter, “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes” feels entirely in tune with its political-cinematic lineage. Any future sequels will have enormous, prehensile shoes to fill, but for now, the series is in good hands.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.