The Supreme Court Could Spell the End of American Democracy

With an array of liberties and executive powers on the docket this term, nothing less than the fate of the republic hangs in the balance. wbentprice / Flickr

wbentprice / Flickr

It has almost gone unnoticed, but amid the daily Sturm und Drang of the Trump impeachment inquiry, the Supreme Court has begun another term. In any other year, the reconvening of the court would be headline news. However, like everything else in the Trump era, the court has taken a back seat to the chaos surrounding our 45th commander in chief.

Nonetheless, the nine justices who constitute our most powerful judicial body are set to decide a bevy of politically charged cases that could impact the 2020 elections and profoundly affect the lives of each and every American. It’s always tricky to predict outcomes in the Supreme Court, but with its five-member conservative majority now firmly entrenched, the panel is poised to swing further to the right as it grapples with issues on LGBT rights, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, abortion, the Second Amendment and “religious liberty.”

It is also likely that the justices will be called on to address at least some aspects of the burgeoning constitutional crisis triggered by the impeachment inquiry and Donald Trump’s continued defiance of Congress.

Here are the potential blockbusters in waiting:

LGBT Rights: Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia; Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda; R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Title VII of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of race, national origin, religion or sex. Three cases argued last week ask whether the act also bans discrimination because of sexual orientation.

The cases were filed by two gay men and a transgender woman, who claim they were improperly discharged. They are represented by a number of prominent lawyers, including Stanford University law professor Pamela Karlan, and David Cole, the American Civil Liberties Union’s national legal director.

In sum and substance, the plaintiffs contend that sexual orientation, correctly understood, is a subset of sex, and is therefore entitled civil rights protection. Their argument squarely pits the court’s conservative justices, who typically adhere to narrow “textualist” readings of statutes, against the tribunal’s liberals, who often favor more expansive interpretations.

During the oral arguments, Justice Samuel Alito articulated the conservative position with his customary belligerence. Noting that the term “sexual orientation” isn’t mentioned in Title VII, Alito charged that the plaintiffs are asking the court to assume a power best left to Congress. “[W]hether Title VII should prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a big policy issue,” he remarked, “different from the one that Congress thought it was addressing in 1964. … And if this Court … interprets the 1964 statute to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, we will be acting exactly like a legislature.”

Alito’s concerns were echoed by Chief Justice John Roberts, who suggested that the plaintiffs want the court to “update” the law. Roberts also worried that such an update would unduly impact “religious organizations” whose doctrines preach against homosexuality.

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco also participated in the arguments, appearing on behalf of the Trump administration and in support of the employers. In August, Francisco filed a brief with the court, confirming that the Justice Department has reversed its Obama-era policy of giving Title VII protections to gay and transgender workers.

As expected, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg pushed back against the conservatives, observing that the court has held that sexual harassment is outlawed under Title VII, even though that term isn’t listed in the act. “No one ever thought sexual harassment was encompassed by discrimination on the basis of sex back in ’64,” she said. “And now we say, of course, harassing someone, subjecting her to terms and conditions of employment she would not encounter if she were a male, that is sex discrimination, but it wasn’t recognized [until later].”

If there is a possible swing vote in the litigation, it might be cast by Justice Neil Gorsuch. In an animated give-and-take with Cole, Gorsuch conceded that whether Title VII should be read to cover sexual orientation was “really close.” He warned, however, of the “massive social upheaval” a victory for the plaintiffs would cause, adding that changes of that magnitude should be “an essentially legislative decision.”

DACA: Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California; Trump v. NAACP; McAleenan v. Vidal

Next month, the court will hear arguments in three consolidated cases that will determine whether the Trump administration’s executive order terminating the DACA program is lawful.

As a bit of background, the program was implemented because Congress was unwilling to ratify the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, which would have provided a pathway to citizenship for a large class of young people (1.3 million, according to some credible estimates) who had been brought into the U.S. as children without the intent to violate American law.

In response to this congressional gridlock, President Obama ordered then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano to introduce the program by way of a formal memorandum, which was published on June 12, 2012. Obama followed up on Napolitano’s memo three days later with an official Rose Garden announcement.

In essence, DACA was designed as an exercise of prosecutorial discretion aimed at reordering the nation’s deportation priorities. Under the program, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—the cabinet-level department that sets deportation policies and oversees the operations of both Border Patrol and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—offers renewable two-year periods of relief from deportation and work authorization to those who meet the program’s eligibility criteria.

In September 2017, the Trump administration announced its intention to end DACA after a six-month grace period. The repeal, however, was subsequently blocked by three federal circuit courts, largely on procedural grounds.

The Trump administration wants a decision on the merits. It contends that the president has the power to repeal DACA because the program lacks congressional authorization.

Nothing is more central to Trump’s nativist agenda than his crackdown on immigration. Ultimately, the Supreme Court could well defer to the president, just as it did in upholding his Muslim travel ban in 2018. If it does, it could turn the dreams of DACA beneficiaries into mass deportation nightmares.

Second Amendment: New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. City of New York, New York

It’s been a long time since the Supreme Court considered a major Second Amendment case. Eleven years ago, the court delivered a landmark triumph to the gun-rights lobby in District of Columbia v. Heller—a 5-4 majority decision written by the late Justice Antonin Scalia that held, for the first time, that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to own and bear firearms.

Heller broke with the great weight of prior scholarship and legal precedent, including the Supreme Court’s 1939 decision in United States v. Miller, which reasoned that the Second Amendment protects gun ownership only in connection with service in long-since antiquated state militias. And while Heller was technically limited to gun ownership in the nation’s capital and other federal venues, the court extended its individual-rights analysis to the states two years later in McDonald v. Chicago, via a 5-4 opinion authored by Alito.

In December, the court will hear the case of the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. City of New York, which has the potential to rival or surpass Heller for its impact on gun rights and gun regulation.

At issue is a New York City ordinance adopted in 2001 that bars residents from taking their guns outside city limits. The ordinance was challenged in a federal lawsuit filed by the National Rifle Association’s New York affiliate and three city residents, who argued that the regulation was unconstitutional in light of Heller.

The plaintiffs lost at both the district court level and before a three-judge panel of the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, which issued a unanimous decision in February 2018, concluding that the ordinance withstood Second Amendment scrutiny under the decision. The Supreme Court agreed in January to review the case.

What made Heller and McDonald attractive to the gun-rights lobby as test cases is that each concerned near-total bans on gun possession by private citizens. Outright prohibitions are rarely easy to justify, and the five-member conservative Supreme Court majority in each instance reinterpreted the Second Amendment to invalidate the prohibitions involved.

Like Heller and McDonald, the New York City case presents an outright ban—not on ownership, but on the right to bear arms beyond the home. Realizing it could easily lose in the Supreme Court, New York City announced in June that it has amended the ordinance and will henceforth permit licensed gun owners to take their firearms to second homes, businesses or shooting ranges outside city limits. In July, the city filed a formal motion with the Supreme Court, requesting that the case be dismissed as moot because the ordinance is no longer in effect. The court denied the city’s motion earlier this month, setting the stage for a Second Amendment showdown.

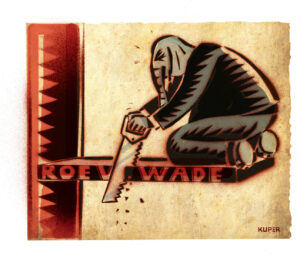

Abortion: June Medical Services LLC v. Gee

In 2014, Louisiana enacted a law that requires doctors who perform abortions in the state to have active admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of any clinic where they provide abortion services. Currently, there are only three abortion clinics in Louisiana. If allowed to take effect, abortion-rights proponents charge, the law would put at least one and possibly two of the clinics out of business.

On its face, the Louisiana statute appears unconstitutional in light of the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, in which the court struck down a nearly identical Texas law. By a 5-3 margin reached after the death of Scalia, the court held that the Texas statute placed an undue burden on women seeking abortions in violation of both Roe v. Wade and the court’s 1992 ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which affirmed Roe’s validity.

Nonetheless, in 2018, the conservative 5th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the Louisiana law. In February, the Supreme Court stayed (i.e., temporarily blocked) the circuit court’s ruling from taking effect, allowing the state’s abortion providers to seek Supreme Court review. Earlier this month, the court agreed to hear the appeal.

Although the case has not yet been set for oral arguments, abortion-rights groups understandably fear the worst. The Supreme Court today is very different from the panel that decided Whole Woman’s Health. Gorsuch has succeeded Scalia, and Justice Brett Kavanaugh has replaced Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the majority opinion in Whole Woman’s Health and retired in 2018. Both Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are known for their anti-abortion views.

When the dust settles on the June Medical case, Whole Woman’s Health could easily be overturned. Worse still, even if Roe technically survives, it could be gutted as a meaningful legal precedent.

Religious Liberty: Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue

In 2015, the Montana Legislature enacted a tax-credit scholarship program for families who send their children to private schools, including religious institutions. In 2018, the Montana Supreme Court struck the law down, declaring that it violates the First Amendment because the program aids religious organizations. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take up the case.

The high court under Roberts has been especially supportive of “religious liberty,” or as the court’s critics allege, religious intolerance. In 2013, the court held in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores Inc. that closely held private corporations with “sincere religious beliefs” can lawfully deprive female employees of health-insurance coverage for contraception. In 2017, in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia Inc. v. Comer, the court struck down Missouri’s policy of denying cash grants to schools owned and operated by churches and other religious institutions.

If the trend continues this term, the court will strike yet another blow to the separation of church and state, and hand another victory to Trump’s fanatical evangelical followers. Oral argument has not yet been scheduled.

The Constitutional Crisis: Cases to be Determined.

In April, Trump took to Twitter, threatening to petition the Supreme Court to intervene in the event House Democrats moved to impeach him. The threat was entirely idle, and the House has initiated impeachment proceedings all the same.

The Constitution vests the House of Representatives with the “sole power of impeachment.” As a result, the House’s decision to impeach isn’t subject to judicial review. We know this beyond any reasonable doubt not only because of the text of the Constitution, but because of the Supreme Court’s 1993 ruling in Walter Nixon v. United States, involving a federal judge who insisted that he had received an unfair impeachment trial in the Senate. The court unanimously rejected the judge’s argument, holding that impeachment presented a nonjusticiable political question. Judge Nixon was convicted and removed from office.

But while the court will not intervene to stop Trump’s impeachment, we also know—courtesy of United States v. Nixon (1974), involving President Richard Nixon—that it will review such impeachment-related matters as the president’s refusal to comply with properly issued subpoenas. In a unanimous decision written by then-Chief Justice Warren Burger, the court ordered Nixon to turn over secret audio tapes made in the Oval Office to Watergate special counsel Leon Jaworski, rejecting Nixon’s claims of executive privilege.

It is doubtful that the Supreme Court wants to get dragged into Trump’s impeachment drama. But like it or not, it may be compelled to examine Trump’s blanket refusal to comply with congressional subpoenas. When and if it does, it will have to determine whether Trump is above the law, or if he, like Nixon, must be held accountable for his actions. The future of American democracy literally could hang in the balance.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.