What’s Really Behind the Media’s Deepfake Panic

The mainstream media insists manipulated video poses a threat to our democracy. It’s a form of fearmongering that only serves the powerful. The Associated Press

The Associated Press

If our mainstream media is to be believed, purposefully deceptive AI-generated imagery, or deepfakes, poses an imminent threat to American democracy. “The future will be riddled with them,” according to Bloomberg, and lawmakers as diverse as Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., and Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom have expressed their alarm. A recent New York Times opinion piece contends, “It will soon be as easy to produce convincing fake video as it is to lie.” The Guardian warns, “The incentive to use deepfakes to injure political opponents is great,” while Fast Company cautions, “Malicious use cases are an increasing concern amid today’s polarized political climate riven by disinformation and fake news.”

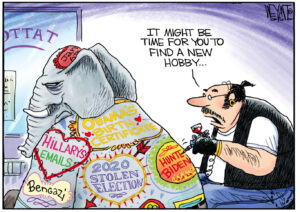

All of these pieces share a basic thesis: Deepfakes have mostly commercial and entertainment-related applications now, but they can easily be weaponized for political gain in the future. Yet like so many allegations of “misinformation,” deepfakes are ill-defined and unproved to bear any political weight. What’s worse, they function as a convenient device for the powerful to flatter themselves and subvert those who challenge them.

Some already have questioned the legitimacy of this scare, which by most accounts entered the popular consciousness in 2017. Last year, The Verge noted that deepfakes haven’t succeeded in swaying public opinion because they’re easy to detect and more likely to confuse viewers than convince them what they’re seeing is real. In June, New York Magazine was more dismissive, noting that “the best examples of widespread deepfaked videos are videos in which Mark Zuckerberg and Barack Obama were deepfaked to warn people not to fall for deepfaked videos.”

Certainly, deepfakes that have gone viral in recent months—celebrity face-swap videos, an animated Mona Lisa, Nicolas Cage appearing in unexpected places—have proved inconsequential. Even a video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, comically slowed down to make her appear drunk and tweeted by President Donald Trump, received more coverage for what it might portend than for any measurable impact it had on the electorate.

Still, for every critical examination of deepfakes, there are scores of credulous ones, even in the same outlets offering platforms to the skeptics. Meanwhile, the political purpose this narrative serves has gone virtually unexamined.

It’s nearly impossible to discuss the deepfake panic without acknowledging its loose parallels with Russiagate and the related “fake news” phenomenon. As with those scandals, which endowed purveyors of promotional clickbait like the Internet Research Agency with the power to steal elections, deepfakes provide the political establishment with a convenient deus ex machina in the event of an unwelcome election result. One can easily imagine Democrats inveighing against them should Trump prevail in 2020.

Indeed, elites have consistently wielded “misinformation” warnings in defense of the status quo. Since the 2016 election, claims have abounded that Russia used social media to “sow discord” among an unsuspecting U.S. public, with a particular focus on issues of racial justice. An NBC News report from May even suggested the Kremlin sought to “manipulate and radicalize African Americans” to “destabilize” the United States—a manifest attempt to undermine racial-justice movements while demonizing a country the U.S. deems an adversary.

“Framing black activism as ‘divisive’ treats the alt-right and white nationalists as if they are on equal footing with those struggling for racial justice,” argued Anoa Changa in The Nation in 2017. “At this time in our history, the struggles and work of black people cannot be reduced to alleged Russian ‘interference’ or ‘propaganda.’”

Similarly, fears of image manipulation have been leveraged to absolve powerful figures of their wrongdoing. On Oct. 3, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University hypothesized that figures such as Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who was discovered to have donned blackface in the 1990s and 2000s, could be subjected to visual manipulation. After these images of Trudeau first surfaced, the article notes that “photoshopped racist blackface and brownface images and memes,” or “cheap fakes,” circulated online, and that the release of the photos “will likely further incentivize … digital dumpstering—combing through bits of digital information, records, data and media, to shame or embarrass candidates or spread confusion for partisan gain.”

While the piece didn’t address deepfakes explicitly, its subtext was clear: Image manipulation could easily be used as a bludgeon against a political candidate. This focus on hypothetical “bad actors” who might seek to smear Trudeau and other politicians, rather than on Trudeau’s very real culpability, only serves to portray a U.S.-allied world leader with a penchant for racist caricatures as a victim.

Nieman Reports’ findings beg the question: If these “bad actors” exist, who are they? There’s no clear answer, but a few clues, unsurprisingly, point to countries the U.S. routinely vilifies. In a 2018 letter to then-Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats, members of Congress stated, “We are deeply concerned that deepfake technology could soon be deployed by malicious foreign actors.” Schiff, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee who co-wrote the letter and has been one of Russiagate’s lead proponents, has already implied, without evidence, that Russia will be to blame.

Additional reports have proved no less speculative. The U.S. Intelligence Community’s 2019 Worldwide Threat Assessment claimed that “adversaries and strategic competitors probably will” use deepfakes to influence the 2020 election, naming Russia, China and Iran as suspects. A “disinformation” report from New York University also specifically mentioned Russia, China and Iran as “candidates to deploy disinformation in 2020”—again, with no proof.

In this context, U.S. intelligence agencies are depicted as trustworthy investigators, ready to safeguard American democracy against shadowy external forces. CNN Business published a multimedia series titled, “When seeing is no longer believing: Inside the Pentagon’s race against deepfake videos,” highlighting the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) deepfake “research” program. In it, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., calls deepfakes “the next wave of attacks against America and Western democracies.” The Washington Post, PBS, The Hill, TechCrunch and a coterie of other media organizations have all uncritically reported on DARPA’s efforts to “defend” the country.

Given their parallels, the deepfake ferment likely will go the way of Russiagate, languishing amid insufficient evidence. But this scare won’t be the last of its kind. If history is any indication, U.S. policymakers and intelligence officials will continue to sound the alarm about misinformation when it suits them, long after deepfakes have receded from the political discourse. Whether they’ll offer anything more convincing than celebrity face-swaps, though, remains to be seen.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.