Who Deserves to Be Called a Progressive?

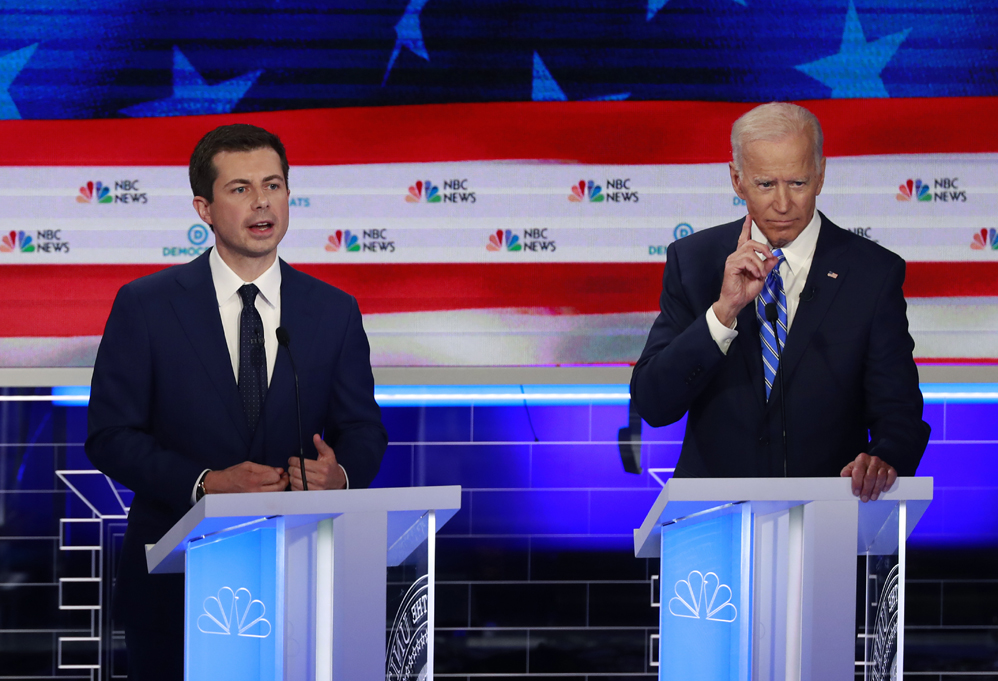

Moderate Democrats like Biden are in denial that the sea change needed to reach goals can coexist with the status quo for the rich. Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, left, and former vice president Joe Biden at the Democratic primary debate in Miami in June. (Wilfredo Lee / AP)

Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, left, and former vice president Joe Biden at the Democratic primary debate in Miami in June. (Wilfredo Lee / AP)

It’s no secret that Democrats today like to call themselves progressive. Even Joe Biden, among the most conservative candidates in the 2020 primary, has claimed, without a trace of irony, that he owns “the most progressive record of anybody running.” Since 2016, the term has only gained currency; after all, who wants to be seen as an impediment to progress? Yet Biden’s idea of what constitutes progress bears little relation to the ideas of Sens. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Bernie Sanders, I-Vt.

A battle is being waged in the Democratic Party about what kind of progress we hope to achieve, and a simple question has determined the sides: Who will challenge entrenched wealth and power and who will not?

The most recent Democratic primary debate helped clarify the divide. Responding to a question about a proposed wealth tax on billionaires, former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke, who voted as a centrist during his time in the House, criticized Warren for embracing a policy he described as “pitting some part of the country against the other.” According to O’Rourke, Warren’s (and presumably Sanders’) proposed taxes are designed to punish the successful rather than lift up the rest of the country. Adopting a similar line of attack, Sen. Amy Klobuchar offered a “reality check” to her Senate colleagues, declaring that “no one on this stage wants to protect billionaires — not even the billionaire wants to protect billionaires.”

“We just have different approaches,” Klobuchar insisted. “Your idea is not the only idea.”

Refrains like these are all too familiar. Moderates frequently claim that both sides fight for the same progressive ideals, that no Democrats want to protect billionaires (or corporations), and that every candidate has the same goals, whether it is universal health care, affordable education or reducing inequality. What separates them, they argue, is their approach toward achieving these goals. Progressives are idealistic, while centrists are pragmatic; the former have it in for the rich, while the latter don’t want to lower anybody’s standard of living. Biden affirmed as much at a fundraiser in New York City in June when he told a throng of wealthy donors that “nobody has to be punished.”

“It’s all within our wheelhouse,” said the frontrunner, promising that “nothing would fundamentally change,” while telling donors that they knew in their gut what needed to be done to help the country move forward.

Biden, like other moderate Democrats, has faith in the powerful to do what’s right — if not for moral reasons, then at least for pragmatic reasons. He believes that we can solve the major problems of our time without addressing the root causes of these problems and that lifting up working people doesn’t require any kind of fundamental change in power relations or the structure of our economy. Billionaires, in other words, can continue to flourish and grow their wealth indefinitely as we also address social and economic problems like income and wealth inequality, stagnating wages, the decline of unions, and so on. CEOs do not have to take a pay cut, the reasoning goes, for workers to receive better wages.

Of course, this notion contradicts the economic reality of the past 40 years, as a recent report on the pay disparity between CEOs and workers demonstrates. According to the report from the Institute for Policy Studies, among S&P 500 firms, almost 80% paid their CEO more than 100 times their median worker pay in 2018, while some of the biggest corporations pay their chief executives more than 1,000 times as much as the average employee. Fifty years ago, by comparison, CEOs typically earned about 40 to 50 times as much as the average employee. To address this huge gap, the study’s authors recommend tax penalties on companies with extreme CEO-worker pay ratios, however this would likely be seen as too “punitive” for moderate Democrats, who don’t believe in “punishing” corporate executives or billionaires (a far cry from someone like Sanders, who has openly declared that “billionaires should not exist.”)

Apologists for the extreme concentration of wealth like to remind everyone how much good certain philanthropic billionaires have done for the world. The fabulously wealthy don’t just create jobs and fund innovation, they maintain; these benefactors also donate millions, even billions, to noble causes that help save and improve countless lives. Yet as journalist Anand Giridharadas points out in his book, “Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World,” the logic behind this worldview is profoundly conservative, paternalistic and anti-democratic:

In an age defined by a chasm between those who have power and those who don’t, elites have spread the idea that people must be helped, but only in market-friendly ways that do not upset fundamental power equations,” writes Giridharadas. “The society should be changed in ways that do not change the underlying economic system that has allowed the winners to win and fostered many of the problems they seek to solve.”

What Giridharadas calls “MarketWorld” is a milieu that consists of “enlightened businesspeople and their collaborators in the worlds of charity, academia, media, government, and think tanks.” MarketWorld elites and ideologues, Giridharadas tells us, promote the idea that social change and progress should be pursued “principally through the free market and voluntary action, not public life and the law and the reform of the systems that people share in common; that it should be supervised by the winners of capitalism and their allies, and not be antagonistic to their needs; and that the biggest beneficiaries of the status quo should play a leading role in the status quo’s reform.”

The most important point here is that the solutions should not be antagonistic to the needs and interests of the winners, who should also be the ones leading the effort to reform the system. This deeply conservative and elitist attitude not only assumes that we can fix the system without really changing it, but that progress is ultimately made by the “winners,” and that the losers should be grateful to their brilliant and benevolent overlords. It is the kind of attitude espoused by Bill Gates’ favorite author, cognitive psychologist (and MarketWorld Thought Leader) Steven Pinker, who defends the status quo in his work “Enlightenment Now,” arguing the economic and political system we currently have is already terrifically progressive, engendering unprecedented innovation that benefits all. Critics of capitalism who call themselves “progressive” and complain about the status quo, Pinker asserts, are in fact disgruntled “progressophobes” who refuse to accept the great achievements of modernity.

Touting progress to defend the status quo is hardly a new strategy. As Albert Camus once observed, “progress” can be paradoxically used to justify conservatism. “A draft drawn on confidence in the future, it allows the master to have a clear conscience,” wrote the philosopher. “The slave and those whose present life is miserable and who can find no consolation in the heavens are assured that at least the future belongs to them. The future is the only kind of property that the masters willingly concede to the slaves.”

Moderate Democrats offer a conservative vision of progress, while “progressives” offer a more radical and democratic version. Recent reports of Pete Buttigieg’s bromance with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who apparently recommended several staffers to Buttigieg’s campaign, reveals that the mayor from Indiana, who is positioning himself as the fresh-faced centrist alternative to Biden, is committed to the same elite and technocratic vision as the former vice president.

During his comeback speech on Saturday in Queens, Sanders made it clear that he has a different view, telling the massive crowd of supporters that those who benefit the most from the status quo will fiercely resist real change. “The question we’ve got to answer,” Sanders said, is “are we prepared to stand up to them and transform this country?”

As more Democratic politicians have come to call themselves progressive, the term, which implies a deep commitment to progress, has lost some of its meaning. All of the candidates in the Democratic primaries claim to fight for progress, but the real question that needs to be asked is what kind of progress they’re actually fighting for.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.