Truthdigger of the Week: The Late Daniel Berrigan, Lifelong Activist for Peace

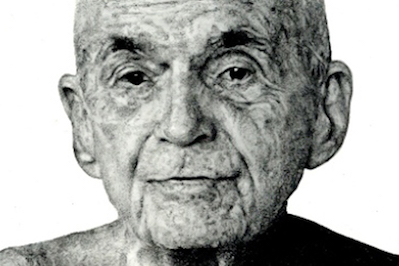

From the dark days of Vietnam to the endless wars of today, the Jesuit priest-poet remained faithful to his mission: protecting the vulnerable, championing resistance and always, always working toward peace. Daniel Berrigan touched uncountable lives with his activism and literary works. (Mr. Fish)

Daniel Berrigan touched uncountable lives with his activism and literary works. (Mr. Fish)

Every week the Truthdig editorial staff selects a Truthdigger of the Week, a group or person worthy of recognition for speaking truth to power, breaking the story or blowing the whistle. It is not usually a lifetime achievement award. Rather, we’re looking for newsmakers whose actions are worth celebrating.

Reviewing the many obituaries extolling the late Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, I cannot help but think that the words depict the passing of a saint. Berrigan, who died April 30, just days before his 95th birthday, would probably object to that title, just as he refused to be called a hero. And yet, a hero in every sense of the word he was, his friends and followers assure those of us who did not have the fortune to meet him during his long, momentous life.

A Jesuit priest from Minnesota, Berrigan was also “a poet, pacifist, educator, social activist, playwright and lifelong resister to what he called ‘American military imperialism’ ” — just some of the roles ascribed to him in the more than hourlong “Democracy Now!” special posted above.

I consider it a failing of my education as a poet that I did not read Berrigan’s work until recently, and I feel blessed (there is no more appropriate word in this case) to have eventually encountered his poetry. To read his free verse is to glimpse the inner workings of faith and heroism, as well as the pain that pacifists must often suffer to achieve their earthly goals. His literary works speak of God, the Trinity and the “risen bread” but also of war, atrocities and — most importantly — resistance. Although in skimming old copies of Poetry Magazine you will find his more spiritual work, he is perhaps better known for more politically charged poems such as “Some,” written in memory of his friend Michael Snyder, a longtime advocate for the homeless, recited by the late poet below.

And here is his poem about his trip to Vietnam with social activist Howard Zinn, on which the two traveled to Hanoi to retrieve three American prisoners of war from the Viet Cong in 1968, a journey that would forever leave its mark on Berrigan:

“Children in the Shelter.”

Imagine; three of them.

As though survival were a rat’s word, and a rat’s death waited there at the end

and I must have in the century’s boneyard heft of flesh and bone in my arms

I picked up the littlest a boy, his face breaded with rice (his sister calmly feeding him as we climbed down)

In my arms fathered in a moment’s grace, the messiah of all my tears. I bore, reborn

a Hiroshima child from hell.

While “Some” invokes a phrase his close friends quote him as saying often—“Don’t just do something. Stand there.”—and highlights with the repetition of “cause” the importance of protest, “Children in the Shelter” is a vulnerable account of the types of violence committed against innocents that were seared into the poet’s mind during the time he spent in Vietnam. The poem, like the poet, bears witness to horrors committed in America’s name by vividly depicting the moving image of the three children — God’s children and no doubt a symbol of the Holy Trinity. The “littlest,” with rice biblically “breaded” on his face, is miraculously “reborn,” like Christ himself, on the page only to morph from that line to the next into the hair-raising, infernal horror of “a Hiroshima child from hell,” the legacy of America’s sins in Japan repeating themselves mercilessly in Vietnam.Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges, who has written on several occasions about Berrigan, whom he called “America’s street priest,” said wrote after Berrigan’s death that “despite his activism, perhaps his greatest contribution was as a writer.”

Indeed, Berrigan was a prolific writer, publishing several books of prose and poetry every year, including valuable radical theology. Below is a list of some of his more notable works, according to the Poetry Foundation:

Time Without Number (1957), which won the Lamont Poetry Prize; Prison Poems (1973); Tulips in the Prison Yard: Selected Poems of Daniel Berrigan (1992); And the Risen Bread: Selected and New Poems 1957–1997 (1998). … His prose includes Night Flight to Hanoi: War Diary With 11 Poems (1968), Testimony: The Word Made Fresh (2004), and No Gods but One (2009). Berrigan also wrote the play The Trial of the Catonsville Nine (1970), which he later shaped into a screenplay. His life is recounted in his autobiography, To Dwell in Peace (1987), and in Murray Polner and Jim O’Grady’s biography Disarmed and Dangerous: The Radical Lives and Times of Daniel and Philip Berrigan (1997).

Yet it is of course his activism that many recall most vividly. Daniel Berrigan, his brother Philip and several others became known as the Catonsville Nine when they used homemade napalm to burn hundreds of draft records on May 17, 1968, in Catonsville, Md. During the action, Daniel Berrigan famously said, “We would like you to know the name of our crime. We would like to assume responsibility for a world, for children, for the future. And if that is a crime, then it is quite clear that we belong in their jails.” The protest would inspire many anti-war actions in the ensuing years before the end of the war in 1975.

The Berrigans and their co-activists were arrested, and while Daniel’s conviction for destruction of government property was under appeal, he went underground for four months. A film about his time as a fugitive from the FBI, “The Holy Outlaw,” was released soon after he was finally caught. Watch it in full below.

Berrigan also started the anti-nuclear Plowshares Movement when he and several activists “broke into General Electric nuclear missile facility in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania [in 1980 and] hammered … on the nuclear warhead nose cones and poured blood onto documents and files.” The birth of the movement was dramatized in the film “King of Prussia,” in which Berrigan’s lifelong friend Martin Sheen acted alongside him. The Plowshares Movement continues to this day, as relevant as it was nearly 40 years ago.

Perhaps Berrigan’s greatest feat, however, was to touch lives and inspire efforts toward peace. Such was the case for author James Carroll, who tells the story of his friendship with Berrigan in a piece for The New Yorker.

It may seem hopelessly narcissistic of me to respond to the death of Daniel Berrigan with this account of his early impact on my life. As if, on the scale of his historic significance, my story matters a damn. Yet perhaps the point is not that my experience is unique but rather that, for all its odd particularities, it is typical. For many, many American Catholics, what it meant to be American and what it meant to be Catholic was radically altered by the witness of Daniel Berrigan. He and his brother, long after the war in Vietnam had ended, continued to insist that U.S. militarism, and the nuclear monstrosity underlying it, was a moral catastrophe. Their insistence lives on as a potent countercurrent to the ongoing drift toward war. And their insistence will always remain as hard evidence that the twenty-first-century American conscience need not have become the frozen sea across which the war on terror sails so blithely on. “This is the worst time of my long life,” Berrigan told The Nation, in 2008. And who did not know exactly what he meant? And, knowing him, who did not see that the United States, at critical turns during the past fifty years, might have gone a different way?

The quote Carroll recalls is from an interview with Hedges in which, on the 40th anniversary of the Catonsville action, Berrigan tells the Truthdig columnist “with a sigh,” “This is the worst time of my long life. … I have never had such meager expectations of the system. I find those expectations verified in the paucity and shallowness every day I live.” As Jeffrey D. Sachs wrote for the Boston Globe in a piece titled “America, Unrepentant Still,” Berrigan did not live to see the day when the U.S. would apologize for or stop its “immoral” wars, as that day moves further and further from our grasp with presidential hopefuls Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump promising to continue to beat the bloody drum that has come be recognized as America’s anthem abroad.

In the “Democracy Now!” special on Berrigan, an account from his friend the Rev. John Dear outlines Berrigan’s approach to terrible times of “paucity and shallowness.”

I remember one of the first things he said to me 35 years ago was talking about resisting death as a social methodology. If you’re going to spend your life resisting death, you learn to live life to the full. If you want to be hopeful, you have to do hopeful things. And he said, remember, “Don’t just do something. Stand there.” … He was faithful. Early on, he was saying, “Make the connections between all the issues as activists and uncover the spiritual roots of our work for peace and justice.” Very beautiful. And that we’re doing this as—you know, he said, “We’re trying to discover what it means to be a human being in an inhuman time.”

The humble Catholic priest, who was indeed a “special gift” as Sachs calls him, lived his days in protest, always working to protect the world’s most vulnerable and defending people who choose resistance as a way of life, just as he did. And although Berrigan spent many months in “their jails,” for breaking “bad laws,” as he called them, he continued to insist that “… yes, we are called to nonviolent resistance, that is very costly. And if what we believe doesn’t cost us something, then we’re left to question its value.”

Thus, for his life’s work, both in presence and in words that have left us with a glowing example of true humanitarianism, the Rev. Daniel Berrigan is our Truthdigger of the Week.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.