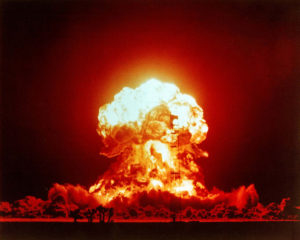

The Goldsboro Incident: How the World Might Have Ended

Two professors paint a chilling scenario of what might have occurred in the wake of a real-life 1961 hydrogen bomb accident in North Carolina.By James G. Blight and janet M. Lang

On Jan. 23,1961, near the city of Goldsboro, N.C., a B-52 carrying two four-megaton hydrogen bombs split apart and crashed in a tobacco field. Several members of the crew were killed. Others survived by parachuting to safety. Neither bomb detonated. On one of the bombs, every safety mechanism failed but one: the “ready/safe” switch in the cockpit. If it had been set to either “ground” or “air” instead of “safe,” the bomb would have detonated.

That’s what happened. Let’s call that the literal history of what is commonly called “the Goldsboro incident.”

But our interest in the incident is not driven primarily by what happened, but by what might have happened if that single switch had moved from the “safe” setting. On our transmedia website, we recently posted our latest animated film, which describes the Goldsboro incident in stark visual images. The film is called “Were We Lucky?” Our answer is that we were indeed.

In the scenario that follows, we draw on our 30 years of research on nuclear decision-making in Washington and Moscow in the early 1960s and apply it to the Goldsboro incident. Here is a fictional but plausible virtual history of what occurs after the crash of the B-52 over rural North Carolina.

It is Jan. 23, 1961. President John F. Kennedy has been in office for three days. He and his top advisers are trying to figure out their schedules, who they should appoint as deputies, how to deal with the thousands of requests and demands from constituents and members of Congress, and how to cope with the human traffic jam outside the Oval Office as ambassadors from around the world jockey to see the president and offer best wishes from their masters back home.

The disorientation that occurs when taking center stage is most profound in the Defense Department. Its new secretary, Robert S. McNamara, enters office with no relevant experience. He does have a reputation for competence and organization and an uncanny ability to get people to work efficiently, which he honed as an executive at the Ford Motor Co. before joining the Kennedy administration. McNamara has said publicly that he did not receive “one piece of paper” from his predecessor, Thomas Gates, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s secretary of defense. In other words, McNamara knows nothing about the way the national security establishment runs, or what its more than 2 million employees around the world actually do. In a national emergency, this could create huge problems, so McNamara hopes for smooth sailing, at least until he gets the lay of the land at the Pentagon.

Around midnight, JFK is awakened by a call on the secure line from McNamara. McNamara says there has been an event somewhere in North Carolina—something has exploded, it seems, but he has no other hard information. As they talk, a Secret Service officer enters the president’s bedroom and asks him to get dressed immediately. He explains that he will lead the president to an underground connecting pod, from which Kennedy, McNamara and other top-level officials will be taken to a secret location inside a mountain in West Virginia to ride out a possible nuclear attack on the East Coast of the United States. JFK looks at the officer and realizes that this is not a joke, not some sort of initiation rite inflicted on new presidents by their subordinates, but a real and present emergency of the first order. Apologetically, the officer informs JFK that the underground complex is not quite finished; it is due to open sometime next year.

Some hours later, Kennedy convenes his Cabinet at the mountain retreat. The Secret Service officer was right: The place is only half finished. Communications, for example, are very patchy and hard to understand. McNamara gives the briefing, having gathered what he can from calls he has placed to other Pentagon officials in the area. McNamara makes the following points:

—A huge explosion has occurred somewhere in central North Carolina.

—Although he has no confirmation, McNamara’s assumption is that a thermonuclear bomb has detonated, a hydrogen bomb being the only known device that can devastate so large a region.

—McNamara estimates that “something on the order of 90,000 to 100,000 people” may have perished in or near the city of Goldsboro, N.C. He emphasizes that this number is only a first approximation, based on little hard data, but it is the best he can do at the moment.

—Air Force surveillance planes have discovered a huge radiation cloud headed toward northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. Low-level aerial reconnaissance reveals refugees—McNamara emphasizes that “refugees” is the word his reporter used—are trudging away from the cities in the affected area. There appears to be no electrical power anywhere on the East Coast. And around hospitals, in particular, one can see hundreds, even thousands lined up in search of medical attention.

—McNamara says that the entire East Coast of the United States is in chaos. He says he can’t speak about the rest of the country, because so far he has been unable to reach anyone west of the Mississippi River. He closes by repeating a comment made to him by an Air Force pilot just minutes before the briefing: “The entire East Coast of the United States looks like a Third World war zone, except that the Third World tends to be in the tropics, whereas this is January on the East Coast of the United States, which is in the midst of a bitter cold spell.” McNamara tells the others that it is possible that tens of thousands of people will soon freeze to death.

—In a brief postscript to the briefing, McNamara says that his subordinates have made repeated attempts to contact the Kremlin, but without success. “We have no idea what they think is going on or what they are going to do about what is going on,” he says. With that, the briefing ends.

Kennedy, visibly shaken and in an unsteady voice, asks for reactions from his advisers. The first to speak is Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay, who has been transitioning from vice chief to chief of staff of the Air Force. LeMay says he is certain that the Russians have attacked the U.S. homeland. He says he believes that the U.S. has a very limited amount of time to respond. LeMay says, “It is obvious that they are testing us—they would like us to capitulate, ask for mercy, whatever, shortly after nuking the East Coast.” LeMay adds that the Russians, whose missiles are notoriously inaccurate, were probably aiming for Washington, D.C., which is roughly 300 miles north of where the bomb detonated. As a precaution, LeMay has placed the Air Force on the highest level of alert short of war. He concludes by requesting that JFK allow him to authorize a massive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union.

JFK’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, shouts, “Are you crazy?” To which LeMay responds, “No, I’m prudent and, unlike you, I know what I’m talking about.”

JFK notes that what happened is still unknown. “Maybe the Russians are not responsible,” he says.

LeMay replies that it doesn’t matter. If the Russians are responsible, then a full retaliatory nuclear attack is what U.S. strategy calls for, and it should be implemented at once. And if the Russians are not responsible, Kennedy should take advantage of this event and order a massive pre-emptive nuclear attack on the Soviet Union, and be done with the Soviet threat once and for all. LeMay, hot with anger because he sees the president hesitating, shouts, “If the Russians didn’t do this to us last night, then they’ll do it some other time when we’ll least be expecting it. So we have to go now, Mr. President. Now!” Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, says he agrees with everything LeMay has said. JFK looks at McNamara, who stares back at him blankly, as if to say, “You’re on your own here.”

At that moment, meeting with his advisers in the Kremlin, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev is told that the Soviet military has no idea what has happened in the U.S., but that his military advisers are certain that the Kennedy administration, assuming they survived the blast, will blame the Soviets. That being the case, Khrushchev’s advisers overwhelmingly recommend a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the U.S.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. The probability of the scenario we outlined is unknown. But it was certainly possible, and many factors suggest its likelihood if the Goldsboro hydrogen bomb had detonated. It must be borne in mind that Jan. 23, 1961, falls three months before the crisis that would shape Kennedy’s view of advisers who counseled confrontation and war: the April 17 Bay of Pigs disaster. His advisers insisted the plan was foolproof: The CIA-backed Cuban exiles would land in southern Cuba and win a battle or two, whereupon the Cuban population would rise up, get rid of Fidel Castro and put someone in charge who was more amenable to “suggestions” from Washington. Although Kennedy tried to scale back the operation, in the end he let it go forward, a passive capitulation to his hawks that nearly got him impeached, and for which he was humiliated in the U.S. and throughout the world.

Had the bomb detonated, would the Goldsboro incident have been another Bay of Pigs? Would JFK have screwed it up by trusting his hawkish advisers? We see no compelling reason to believe he would have done otherwise.

Khrushchev, for his part, is also in deep trouble if the Goldsboro hydrogen bomb detonates. He and Kennedy have never met. In January 1961, their correspondence, which would be so important in the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, has not gone beyond an exchange of pleasantries. Back channels do not as yet exist. So decisions in Washington and Moscow would have to be made in almost total ignorance of what the other side was up to, in what we call an “empathy-free zone,” the zone in which the Cuban missile crisis began. Only this time, tens of thousands of people have been killed, many more are injured or ill, and the social fabric of the eastern United States, including Washington and New York, has been shredded. In the crisis that ensues, neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev will have the means to beat back worst-case scenarios with facts about the adversary’s decision-making. The relevant facts are simply unavailable. The Cold War is raging. Where facts are few; paranoid fantasies are sure to tread.

In his 2013 best-selling book “Command and Control,” Eric Schlosser examines all the known accidents involving U.S. nuclear arsenals. The book is a cure for those afflicted with apathy about the nuclear threat. The scenarios, including the Goldsboro incident, are very scary, and in some cases, our escape from nuclear war seems almost as miraculous as that in the October 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Had the damage not been contained, a few of the accidents might have led to a post-apocalyptic condition brilliantly portrayed in Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Road” and the 2008 film that is based on the book. McCarthy’s story is bleaker than bleak: a panorama of a civilization destroyed in nuclear fire, as a father and son walk from the northeast United States to the Gulf of Mexico, where the father believes they have a better chance of surviving a little while longer because it is warmer—or so he hopes.

Schlosser ends his book this way:

We have a false sense of comfort. Right now thousands of missiles are hidden away, literally out of sight, topped with warheads ready to go, awaiting the right electrical signal. They are a collective death wish, barely suppressed. Every one of them is an accident waiting to happen, a potential act of mass murder. They are out there, waiting, soulless and mechanical, sustained by our denial—and they work.

And that is why, as we say in our short film “Who Cares About the Cuban Missile Crisis”, “We’ve got to get rid of the [nuclear] weapons.”

James G. Blight and janet M. Lang are on the faculty of the Department of History and the Balsillie School of International Relations at the University of Waterloo, in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. They are best known for their work on the Cuban missile crisis, and for their embrace of a transmedia platform, Armageddonletters.com, where they have posted original films, a graphic novel, podcasts, blogs and a description of their recent book, “The Armageddon Letters: Kennedy/Khrushchev/Castro in the Cuban Missile Crisis” (2012).

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.