The Dangerous Rush to Judgment Against Julian Assange

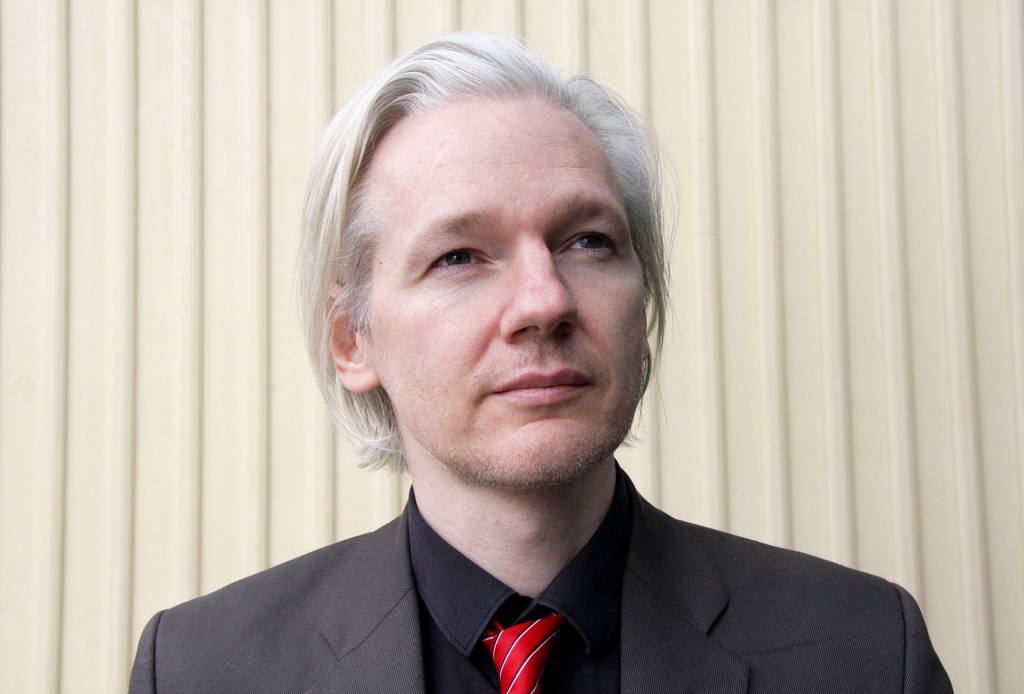

Whether you love the WikiLeaks founder or regard him as a threat to democracy, he is entitled to the presumption of innocence until proven guilty. Espen Moe / CC BY 2.0

Espen Moe / CC BY 2.0

After years of speculation, we now know that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been accused by the Justice Department of committing crimes against the United States. We know this because an assistant U.S. attorney named Kellen S. Dwyer screwed up and inadvertently disclosed in a motion filed on Aug. 22 in an unrelated case that Assange has been secretly charged in an accusation that has been placed under seal.

The unrelated case is pending in the Eastern District of Virginia against Seitu Sulayman Kokayi, 29, who, according to The Washington Post, is linked to international terrorism and whose father in-law has been convicted of committing terrorist acts.

What we don’t know about the prosecution of Assange is virtually everything else.

For starters, we don’t know whether the charging document lodged against Assange is an indictment or simply a complaint. The difference is important because indictments are handed down by a grand jury, while complaints are generated by the Justice Department on its own initiative and are usually preliminary and superseded by subsequent indictments. If the charging document is an indictment, it would imply the department is ready to roll, and that a trial will commence as soon as Assange is arrested and extradited. (The Supreme Court has held that federal criminal trials cannot start in the defendant’s absence.)

More important, we don’t know the nature of Assange’s alleged offenses, when they allegedly were committed, or when the charges against him were filed.

Has he been charged under the Espionage Act of 1917 for publishing classified material? Has he been accused of hacking in violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act in connection with the publication of emails taken from the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 presidential election campaign, or for receiving and publishing intelligence documents related to the CIA last year? Does he stand accused as a principal (primary actor), or is he viewed as an aider and abettor or a co-conspirator, either of Chelsea Manning, who leaked national-defense material to WikiLeaks in 2010, or the 12 Russian military officers who were indicted this July by special counsel Robert Mueller for stealing the Democratic National Committee’s emails?

We also don’t know whether Mueller’s office is responsible for going after Assange, or whether former Attorney General Jeff Sessions can claim the credit. In an April 2017 press conference, Sessions announced that arresting Assange was “now a priority.” The same month, Mike Pompeo, then director of the CIA and current secretary of state, remarked in a speech delivered to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C., think tank: “It is time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is—a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia.”

It’s possible that Pompeo is right, and that Assange is in fact a Russian agent and not a legitimate publisher entitled to First Amendment protections. But possibilities are not proof. Speculation is not evidence.

It’s vital to remember in this respect something we are taught in high school civics: Even the lowliest of defendants in our criminal justice system is presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Whether you love Assange and see him as a source of transparency in an age of government secrecy or regard him as a pro-Trump threat to democracy, he is entitled to that presumption. Anything less represents a dangerous rush to judgment that undermines the rule of law.

Writing in The Intercept last week, Glenn Greenwald decried the intensifying support for Assange’s extradition, not only on the right, but also among liberal Democrats who feel stung by Trump’s election and incensed by the help he may have received from Russian intelligence in scoring his improbable victory at the polls.

Trump, who professed his “love” for WikiLeaks during the campaign, is now on board with targeting Assange. Ever the opportunist, the president could easily flip back to the position he advocated in 2010 in an interview with Fox News, when he declared that Assange should receive the death penalty if brought to the U.S.

It’s important not to get swept up in the anti-Assange mania afoot today, not only because the mania undercuts the presumption of innocence, but because of the significant dangers posed to the First Amendment. As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) noted in a 34-page analysis published in 2017:

“While courts have held that the Espionage Act and other relevant statutes allow for convictions for leaks to the press, the government has never prosecuted a traditional news organization for its receipt [and publication] of classified or other protected information.”

In the trial of Assange, the government no doubt will contend that WikiLeaks is not a legitimate news organization. It is unlikely, however, the Trump Justice Department will be able to draw a principled line between publishers that merit First Amendment protection and those who do not.

The Obama administration declined to indict Assange because of what was described as the “New York Times problem”—that if Assange were charged, The New York Times, the Post and The Guardian, among others, would also have to be prosecuted for publishing classified material.

To get around the “New York Times problem,” the Trump DOJ will have two basic options:

First, it could elect to blow through the problem, arguing that just because the Espionage Act has never been applied to a publisher in the past, there’s a first time for everything. Indeed, as the CRS’ 2017 analysis notes, the text of the act actually prohibits both the illegal acquisition and the subsequent dissemination of classified material.

Nor would the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in the Pentagon Papers case preclude the prosecution of Assange. The ruling in the Pentagon Papers case held only that the government could not enjoin The Times from publishing the material disclosed by Daniel Ellsberg. It did not hold that The Times could not be prosecuted post-publication. Although the Nixon administration decided as a matter of policy not to do so, the court did not resolve whether it could have charged The Times. The issue still has not been put to rest.

Should the Trump administration succeed in obliterating the “New York Times problem,” no publication would be safe from the administration’s vengeance and overreach. Small independent news organizations—think, Truthdig, The Intercept, The Nation and others on the left—would be especially vulnerable.

Second, in lieu of a blunderbuss assault on the “New York Times problem,” the Justice Department might argue that even if WikiLeaks is considered a publisher, the First Amendment should not apply to foreign news outlets.

Surprisingly, there is scant case law on the subject. What little there is, however, suggests that even if foreign publishers may not be seen as beneficiaries of the First Amendment, the amendment safeguards the rights of Americans to read material of their own choosing.

As a little-known and long-deceased federal district court judge, Stanley Weigel, held in 1964 in an obscenity case:

“Even if it be conceded, arguendo, that the ‘foreign press’ is not a direct beneficiary of the Amendment … the Amendment does protect the public of this country. … The First Amendment surely was designed to protect the rights of readers and distributors of publications no less than those of writers or printers. Indeed, the essence of the First Amendment right to freedom of the press is not so much the right to print as it is the right to read.”

I am not a fan of Assange. Like many, I fear that he has gone over to the dark side in the global battle against regressive nationalism. But I am not willing to sacrifice or bend the First Amendment—not even a little—in an effort to silence him or rush him to some kind of American justice.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.