Mexico’s Breaking Point

So deeply has this incident shaken the country that, as author Ruben Martinez describes it, “To understand the historical significance -- and the moral and political gravity -- of what is occurring, think of 9/11, of Sandy Hook, of the day JFK was assassinated.” A protester cries as she's rounded up by police and human rights observers try to reach her during a march near the airport in Mexico City on Thursday. Protesters marched to demand authorities find 43 missing college students, trying to step up pressure on the Mexican government on a day traditionally reserved for the celebration of the 1910-17 Revolution. AP/Marco Ugarte

A protester cries as she's rounded up by police and human rights observers try to reach her during a march near the airport in Mexico City on Thursday. Protesters marched to demand authorities find 43 missing college students, trying to step up pressure on the Mexican government on a day traditionally reserved for the celebration of the 1910-17 Revolution. AP/Marco Ugarte

This Friday marks the two-month anniversary of the apparent slaying of the Ayotzinapa students — an event that has triggered Mexico’s most serious political crisis in decades.

Outrage at the 43 students’ fate fills the Mexican streets on a daily basis. Over the last two weeks, demonstrators have occupied and burned down government offices, set fire to the door of the presidential palace in Mexico City, and blocked access to the airport in Acapulco along with many major roads across the country. Last month, over 50,000 people marched by candlelight onto Mexico City’s central plaza chanting, “Alive they were taken. Alive we want them back!”

Thursday’s protests, expected to be the biggest yet, are taking place throughout Mexico and across the globe.

So deeply has this incident shaken the country that, as author Ruben Martinez describes it, “To understand the historical significance — and the moral and political gravity — of what is occurring, think of 9/11, of Sandy Hook, of the day JFK was assassinated.”

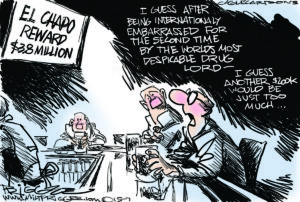

For many, this is a crisis that attests to the governmental corruption and collusion at the core of a failed state. It represents the impunity with which Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto masks state repression as acts of localized and disconnected casualties of the drug war. The Ayotzinapa disappearance seems to have exposed, once and for all, the unholy union of Mexico’s political institutions and organized crime.

The 43 students are still missing after their abduction on Sept. 26 in Iguala, a city in the southwestern state of Guerrero. In a school tradition, the young men, who were mostly freshmen from a local teaching college, had been taking over passenger buses and occupying toll stations on highways, asking for donations in exchange for letting automobiles pass. That evening, municipal police officers opened fire on the students, killing six and reportedly torturing one to death before peeling his face off and dumping his mutilated body in plain view. The 43 were then said to be handed off to the Guerreros Unidos, or United Warriors drug gang, which reportedly took them to a municipal garbage dump in the countryside around the nearby town of Cocula. Their bodies were allegedly thrown in a ravine where they said to be “stacked up like firewood” and burned for two days.

The orders reportedly came from Iguala Mayor José Luis Abarca, who was apparently concerned about the students’ plans to demonstrate outside an event hosted by his wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda. Half of Iguala’s “imperial couple,” the former first lady comes from a family of well-known drug traffickers, with a father and three brothers who are known members of the United Warriors. Iguala and its surrounding area are all under the control of the gang, and the municipal police are known to be on their payroll. Abarca himself has been said to have close ties with drug gangs in Acapulco, and he was accused in 2013 of shooting a kidnapped activist in the face.

It took a month for the fugitive mayor to be arrested, and two weeks before Nieto would define the young people’s disappearance as a national and not merely a local problem. Despite Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam’s insistence that “Iguala isn’t the Mexican state,” his [now infamous] statement, “Ya me cansé” — or “I’ve had enough” — has become the rallying cry of an increasingly restive population.This is because the Iguala massacre is only the latest gruesome attack on Mexico’s youth to evoke the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre as well as the so-called Dirty War of the 1970s.

For instance, on June 30 Mexican soldiers are accused of brutally killing 21 youth in a warehouse in Tlatlaya, about 90 miles from Mexico City. Officials immediately attempted to whitewash the incident by announcing that the dead were kidnappers who had died in a gunfight. It was only after independent reporting by The Associated Press and a public expose by a witness in the Mexican media that a fuller picture about the incident emerged. Apparently, the U.S.-backed Mexican military assassinated dozens of youth in cold blood.

Since 2006, 30,000 people in Mexico have been registered as missing. Since 2007, 100,000 people have died in violence linked to organized crime. In a 2013 investigation by Human Rights Watch, it was revealed that in 149 out of 250 disappearance cases, there was “compelling evidence” that state agents were involved.

If these figures speak to the failure of the Peña Nieto government, it should also be noted that during the first year of his presidency in 2013, Mexico had dropped to 106 in Transparency International’s global corruption report, down from 51 in 2001.

As journalist Anabel Hernandez, herself a target of the drug cartels, made clear in a Guardian commentary last week, “Since Peña Nieto came to power, there have been grave regressions in Mexico, one of which is the abhorrence of transparency and public accountability, a move that was led by the presidential office and replicated by other governmental institutions.”

She continued: “What else can be expected of this soiled government? In recent months, the military and the attorney general have presented false reports regarding crimes. Official information shows that in 2006 the number of criminal complaints not investigated by the federal government amounted to 24,000; in 2013, the number was 63,000. In Peña Nieto’s administration, law enforcement has become increasingly slow and pathetic.”

One response to the bloodshed, which should now return to haunt him, was the president’s suggestion in 2013 that the media no longer pay so much attention to violent crime.

But Ayotzinapa has pushed Mexico to the brink. As the protest movement expands exponentially, national newspapers like La Jornada now run headlines such as “Fuera Peña Nieto!” or “Out with Pena Nieto!” Added to the fray, the president must answer questions about the unfolding scandal involving his new $7 million home.

Whatever the future holds for the current administration, the protesters are proving it’s impossible to make people disappear when the whole world is watching.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.