Before Occupy, There Was People’s Park

A new book about the 1969 battle in Berkeley is striking in its implications for a military takeover in an ostensibly democratic society. Heyday

Heyday

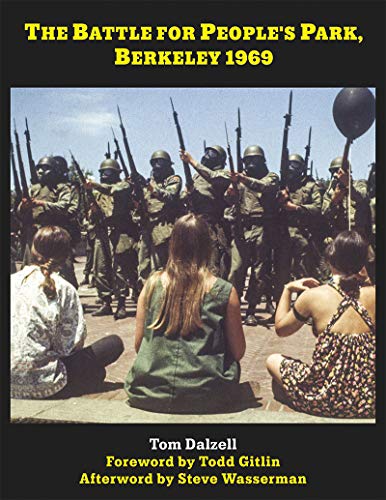

“The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley, 1969”

A book edited by Tom Dalzell, foreword by Todd Gitlin, afterword by Steve Wasserman

There is nostalgia for Ronald Reagan in 2019. He is widely viewed in the media and elsewhere as a sensible Republican, a mainstream conservative, a reasonable man—the polar opposite of Donald Trump, the dangerous buffoon now occupying the presidency. Many pundits pine for the “Gipper,” the genial, affable president who chatted with reporters and sipped drinks with some of his political adversaries.

That view is tragically wrong. Reagan and his odious chief of staff and later attorney general, Ed Meese, were central players in some of the most horrific suppressive acts of the rebellious 1960s in the United States. They and various local officials in Berkeley and Alameda County, California, were responsible for some of the most egregious and systematic acts of violence directed against peaceful demonstrators and protesters in recent American history.

A powerful new book, “The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969,” provides a far more realistic vision of one of the most crucial series of events of the turbulent ’60s. Among many other things in this marvelous volume, edited by longtime Berkeley writer and denizen Tom Dalzell, it reveals Reagan as the cruel and malevolent governor who unleashed horrific terror against Berkeley students and others in May 1969. It provides powerful evidence of how Reagan used his “tough” stance against the Berkeley rebellion as a steppingstone to the White House. His campaign against Berkeley students propelled him to national political prominence and fueled his reactionary agenda in California and later in the nation.

This book is a definitive account of the battle for People’s Park, a 50th anniversary gem. The volume contains scores of eyewitness statements, more than 200 photographs (many never previously published), and some highly perceptive longer pieces about those tumultuous events in 1969. A brief disclosure: A few of my personal recollections are in this volume; I spoke to Dalzell and sent him an email. I was a first-year faculty member at Berkeley in 1969 and generally supported the People’s Park struggle. Moreover, I was (and remain) an active member of the bar and participated robustly in the legal efforts to get people out of jail, released without bail, and later in other legal proceedings. I remain a UC(LA) faculty member and now only modestly practice pro bono social justice law.

This book appropriately begins with what is widely known as “Bloody Thursday.” Todd Gitlin’s opening essay provides the specific historic context. In April 1969, several hundred local people began turning a University of California parking lot wasteland south of the main Berkeley campus into a utopian park. They installed swings for children, they made gardens, they played music, they offered food to those in need, and they smoked lots of marijuana—in short, People’s Park reflected the strong counterculture of the era. The book has numerous engaging photographs and recollections of those efforts. I went there on several occasions and thought it was a useful and valuable challenge to university authority. But I also thought that the efforts in People’s Park diverted energy from opposition to the grotesque and illegal war in Vietnam.

It all came crashing down on Thursday, May 15 when Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns, capitulating to Reagan, cracked down on the park. Police sealed it off by bulldozing the gardens and erecting a large fence around the entire area. At a noon rally on campus, Student Body President-Elect Dan Siegel exhorted the large crowd to “take the park.” Violence soon ensued.

Students and others then marched down Telegraph Avenue. They were met with entirely unexpected police brutality. In the end, one man, James Rector, was killed and another, Alan Blanchard, was blinded. The book reveals Reagan’s comments: “You use whatever force is necessary.” And, more ominously: “The death of James Rector should again serve as a bitter lesson that violence and revolution will lead to nothing but chaos and further bloodshed.” Meese’s comment, entirely reflective of the man’s lifelong character and mentality, was even worse: “James Rector deserved to die.”

In one of my brief comments in the volume, I recalled that I was teaching at the time in the campus building not far from Telegraph Avenue, and experienced tear gas in my class. I dismissed my students. For me, by then, the issue had become police brutality far more than the occupation of the park itself. Dalzell has assembled numerous personal accounts as well as shocking photographic evidence of police malice and protester injuries. One of the most disconcerting documents in this book is the list of known victims of the May 15 shootings. This is the true legacy of Reagan.

That legacy grew more pernicious the following day. He ordered three battalions of the 49th infantry brigade of the National Guard into Berkeley. The military occupation included a group of soldiers who were billeted at People’s Park, further inflaming students and other park supporters. The photographs and personal accounts in “The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969” are striking—and utterly shocking in their implications for a military takeover (including de facto martial law) of a city in an ostensibly democratic society. Reagan, quoted in the book, blamed the Berkeley faculty and their advocacy of civil disobedience for the violence.

It got worse. In one of the most chilling chapters of the book, “Terror from Above,” May 20, 1969, is revealed as one of the darkest days in the entire history of American higher education. As the book reports, a police officer with a bullhorn announced: “Chemical agents are about to be dropped. I request that you leave the area.” What followed was an army helicopter that flew over the UC Berkeley campus dropping CS gas causing burning sensations, extensive coughing, and difficulty breathing. Wind carrying the gas wafted throughout the campus and as far away as a local elementary school.

The book chronicles many individual reactions. Reagan labeled the helicopter incident—the first bombing of an American campus—“a battlefield decision.” Victims saw it differently. One had to be taken to an emergency room with mucous membrane inflammation. Others vomited. Some had burning eyes. I was a direct victim of the gas attack and, lacking a gas mask like other opponents of the police and military, felt nauseous for a couple of days after the bombing. This grotesque helicopter attack rightfully goes down in infamy, properly documented in this extraordinary book.

“Boxed and Beaten” is another unnervingly compelling chapter in Dalzell’s masterpiece volume. This chapter documents one of the most severe incidents of massive police brutality and misconduct in Bay Area history. Known as “Operation Box,” 482 people were arrested on Berkeley’s main street, Shattuck Avenue, on May 22, 1969. This mass arrest followed a faculty-led march from the campus to downtown Berkeley. National Guardsmen drove people—mostly but not entirely protesters—into a Bank of America parking lot. Soon they were arrested and jailed, mostly without violence. The book contains accounts from several of the people on the scene, many of whom sought peacefully to leave but were arrested nevertheless.

The egregious violence occurred after they arrived at the Santa Rita Jail in Dublin 30 miles east of Berkeley. The male arrestees were subjected to horrific violence by various members of the Alameda County Sheriff’s Department, an agency under the leadership of Sheriff Frank Madigan with a well-deserved reputation for police brutality at the time. The accounts in the book are devastating. They detail the vicious beatings, oral threats, and other indignities that newly arrived prisoners suffered during their long night of confinement at Santa Rita.

And they are accurate. I was one of the first lawyers to arrive at that monstrous penal facility. As I indicate in my own brief account in the book, I remained there during the late afternoon and all through the night, trying to get prisoners’ information in order to return to court to get them released as soon as possible. I witnessed many sheriff’s deputies strike people on the sides of their heads while they were lying on the ground. If prisoners even moved, deputies kicked them in their backs or legs. I had seen (and had personally experienced) comparable brutality in my civil rights days in the South; this was as bad or worse.

I was personally threatened only once: After about five hours, I asked a deputy if I could use the restroom. He refused and said he might arrest me if I asked again. I fortunately found a superior officer who directed me to a men’s room. My view is that the Sixth Amendment right to counsel, under these circumstances, also includes the counsel’s right to pee.

The best and most comprehensive account in “The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969” is Bob Scheer’s “A Night at Santa Rita,” originally published in Ramparts magazine in August 1969. It is a powerful confirmation of the viciousness of the police. Scheer, Truthdig’s editor-in-chief, describes the terror with frightening detail. This is the stuff of Nazi Germany, Algeria before the liberation, Pinochet’s Chile, Argentina of the generals, and so on ad nauseam. All this reflected the cruel and intentional interference of Reagan and his chief henchman, Meese. Not surprisingly, charges from all 482 arrests were dismissed.

The book closes with the Memorial Day March, which occurred on Friday, May 30, 1969. It was huge: Somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 people marched, representing every conceivable progressive and sectarian left group in the Bay Area. Entirely peaceful, its objective was to force the removal of the cyclone fence around People’s Park. That failed; the fence remained but the march had some mixed results. It manifested the determination of thousands of people that Berkeley would not tolerate a military occupation. At the same time, it was also officialdom’s sophisticated way to allow masses of people to let off steam while essentially changing little or nothing politically.

What, then, are readers to make of all this? Steve Wasserman offers some perceptive historical observations in his afterword. He places the battle for People’s Park in the longer history of radical protest in Berkeley. He notes the controversy of the protest against the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1960; the great civil rights sit-ins of spring 1964 at the Sheraton Palace Hotel in San Francisco and the Auto Row demonstrations, peopled largely by Berkeley students; the historic free speech movement of fall 1964 on the Berkeley campus; the historic antiwar teach-in organized by the Vietnam Day Committee in May 1965; the efforts to block troop trains in Berkeley in 1965; and the Third World Liberation Strike at UC in February 1969 to create ethnic studies programs. This is the context for the People’s Park battle.

It is crucial to go beyond the institutional hooliganism of Madigan and even Reagan. Reagan used the affair to crack down on the University of California and on public higher education generally. He tapped a broad and deep anti-intellectualism in California to reduce public funding for the university. Ultimately, this led to substantial tuition and massive student debt. These remain major problems in the early 21st century. Reagan encouraged a politics of resentment that subsequent demagogues like Donald Trump could likewise employ in their own appeals for public support.

The implications of People’s Park go far beyond a modest strip of land on University of California property. In 1969, I didn’t think that the transformation of that barren plot into a small island of peace, tranquility, goodwill, and sisterhood and brotherhood would transform the world and do much to end the violence of the war, much less the broader patterns of imperialism and oppression throughout the world. My view hasn’t changed. But I think the park should have been defended, and more aggressively. The battle for the park in 1969, I believe, was a defeat.

“The Battle for People’s Park, Berkeley 1969” provides some of the most extraordinary source material for a crucial moment in the agitation era of the 1960s. We need to understand that era if we are to learn its lessons (especially its mistakes) and confront the challenges of the new century. Truly, the future of humanity, and of the planet itself, depends on it.

Your support is crucial…

With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.