It’s Now or Never for John Roberts

The chief justice gets a shot to show whether what he claims to be an “independent judiciary” is true in three blockbuster cases. President Donald Trump, left, walks with Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts. (Alex Brandon / AP)

President Donald Trump, left, walks with Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts. (Alex Brandon / AP)

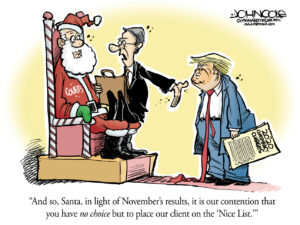

In November 2018, after President Donald Trump blasted a federal jurist as an “Obama judge” for overturning his new restrictions on political asylum, Supreme Court Chief Justice Roberts issued a biting reply in a statement to the Associated Press: “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them. The independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for.”

Never one to shy away from verbal combat, Trump tweeted out a snarky rejoinder: “Sorry Chief Justice John Roberts, but you do indeed have ‘Obama judges,’ and they have a much different point of view than the people who are charged with the safety of our country.”

I’m sorry, too, Mr. Chief Justice, but I also believe that in general there are significant differences between judges appointed by liberal and conservative presidents. This is especially true of the justices who sit on the Supreme Court.

Academic researchers who study the ideological alignment of Supreme Court justices have consistently found the political leanings of judges are very important, particularly in high-profile cases. Common sense and real-world experience also counsel that judicial politics matter. Indeed, if ideology made no difference in the way judges render decisions, we would never have stressed over Trump’s nominations of Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

I’m willing, however, to be proved wrong. And by the end of the Supreme Court’s current term, Roberts, who is now the court’s most prominent swing voter, will have an opportunity to do just that when he and his colleagues decide three cases that could determine whether Trump is immune from both congressional and state oversight:

- Trump v. Vance, which deals with the constitutionality of a subpoena issued by a New York grand jury, demanding the production of nearly 10 years’ worth of the president’s financial papers and his tax returns.

- Trump v. Mazars, concerning a subpoena issued by the House Committee on Oversight and Reform to the president’s accounting firm, requesting a variety of Trump’s private financial records; and

- Trump v. Deutsche Bank, concerning a subpoena issued by the House Financial Services Committee, seeking similar records from Deutsche Bank and Capital One, the president’s two favorite lenders.

In each of the cases, lower courts ruled against the president. The Supreme Court was under no obligation to review any of them, but agreed on Dec. 13 to review all of them at the president’s request.

Although the Supreme Court could find a way to resolve the cases on narrow grounds, the cases have the potential to redefine both the separation of powers between Congress and the president and the distribution of authority between the federal government and the states.

The court could also use the cases to overturn or distinguish and restrict the longstanding precedents on executive privilege and presidential immunity established in United States v. Nixon (1974), and Clinton v. Jones (1997).

Both the Nixon and Clinton cases were the products of investigations similar to the current undertaking to impeach and remove Trump from office. In Nixon, the court ordered then-President Richard Nixon to turn over clandestine White House audiotapes to Watergate Special Counsel Leon Jaworski, rejecting Nixon’s invocation of executive privilege. In the Clinton appeal, the court held that a sitting president is not immune from civil litigation initiated by a private party in federal court for acts done before taking office and unrelated to his official duties as president. Impeachment, the court noted, is the federal remedy for addressing a president’s public misconduct.

Trump has made his position on expansive executive power unmistakably clear from his earliest days in office. Speaking at the Turning Point USA Teen Student Action Summit in Washington, D.C., in July, he famously claimed that under Article II of the Constitution, which sets forth the powers of the presidency, “I have the right to do whatever I want as president.”

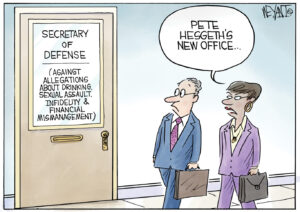

While Trump’s mastery of the Constitution is meager and often downright embarrassing, the views of his primary legal advocate—Attorney General William Barr—are well-developed and dangerous.

As I explained in a previous Truthdig column, Barr is a leading proponent of the “unitary executive theory.” Developed by right-wing legal scholars in reaction to Nixon’s ouster, the theory dates back to the presidency of Ronald Reagan. It asserts, as University of Baltimore law professor Garret Epps has explained, that because the Constitution vests executive power in a single president, any attempt to limit the president’s control over the executive branch is unconstitutional.

In its more robust iterations, the theory goes even further, verging on a platform of presidential supremacy. As professors Karl Manheim and Allan Ides of Loyola Law School in Los Angeles observed in an oft-quoted 2006 academic paper:

In its stronger versions, it embraces and promotes a notion of consolidated presidential power that essentially isolates the Executive Branch from any type of congressional or judicial oversight. And it is much more than an academic theory. Rather it is an operative way of thinking about and applying Executive Branch power that has had and will continue to have real-world consequences for our republic and for the international community.

Barr makes no secret he adheres to the robust version. In an astonishing address delivered Nov. 15 at the Federalist Society’s annual lawyers convention in Washington, D.C., he advanced a vision of virtually unchecked presidential power. Attacking what he vaguely referred to as “the left” for promoting a “scorched-earth, no-holds war of ‘Resistance’ against” the Trump administration, he contended that “since the mid-’60s, there has been a steady grinding down of the executive branch’s authority that accelerated after Watergate.

“The premise [of the Resistance] is that the greatest danger of government becoming oppressive arises from the prospect of executive excess. So, there is a knee-jerk tendency to see the legislative and judicial branches as the good guys protecting society from a rapacious would-be autocrat. This prejudice is wrong-headed and atavistic.”

Invoking the Founding Fathers, whom he maintained supported sweeping presidential powers, he lamented the many lawsuits that have been filed to block Trump administration policies, concluding that “it is critical to our nation’s future that we restore and preserve in their full vigor our founding principles. Not the least of these is the framers’ vision of a strong, independent executive.”

Barr’s Justice Department will play the role of amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) in the three financial records cases now pending before the Supreme Court. Together with Trump’s private attorneys, the department will be well-positioned to advance Barr’s views on executive authority and his bare-knuckle defense of Trump in what is shaping up as a constitutional showdown for the ages.

Are Chief Justice Roberts and the other members of the nation’s highest judicial body up for the challenge? Are they prepared to demonstrate that there are no such things as “Trump judges?” We’ll have an answer by the end of June.

Your support is crucial…

With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.