Jack Daniel’s vs. the People’s Right to Spoof Corporate America

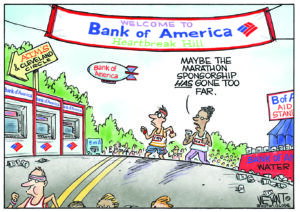

A little-noticed 9-0 decision points ominously toward a post-parody culture. The Supreme Court and a bottle of Bad Spaniels. Image: Truthdig.

The Supreme Court and a bottle of Bad Spaniels. Image: Truthdig.

Amid all the outrage and hair-pulling in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decisions on affirmative action, student debt relief and LGBTQ rights, the weirdest case on the 2023 docket got lost in the fray. This is too bad, because the implications of the little-noticed June 8 decision are as consequential and far-reaching as those other, more high-profile rulings.

It sounds like a parody of a corporate lawsuit, which perhaps explains why mainstream news outlets have treated it that way. In 2014, a Phoenix-based dog toy company called VIP Products released a vinyl chew toy shaped like the iconic Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle. The label read “Bad Spaniels” in the recognizable Jack Daniel’s font, and spoofed the rest of the original label text with a series of dog poop jokes. “Old No. 7 Tennessee whiskey,” for instance, became “Old No. 2 on your Tennessee Carpet.” It was one of a series of 14 parody liquor-bottle dog toys produced by VIP, including “Heinie Sniffin’” and “Blameson.”

While none of the other lampooned brands seemed much offended by the joke, Brown-Forman Corp, the owner of the renowned Louisville-based distillery, was not amused. The liquor giant promptly filed a trademark infringement suit that claimed the chew toy was hurting the sales and diminishing the worldwide reputation of Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey.

In 2020, the San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals concluded “Bad Spaniels” presented no discernible threat to Jack Daniels’ bottom line; nor did it create “confusion in the marketplace,” declaring the dog toy “an expressive work protected by the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment.” It was a clear-cut decision, as VIP’s parody easily fit into the legal parameters of what constituted fair use and artistic license. (The judge in the case refrained from noting that you’d have to be pretty stinking drunk to confuse a vinyl chew toy with a fifth of Jack.)

The court’s redefinition of what qualifies for First Amendment protection sets an extremely troubling precedent when it comes to the future of parody as a form.

Jack Daniel’s found the decision no funnier than the “Bad Spaniels” chew toy itself. They appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case.

There was a large body of precedent for the Roberts court to consult in considering Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC. Trademark fair use laws, sometimes known as parody laws, have been on the books since 1983. The vast majority of trademark suits involve marketing; one company suing another over, say, the co-optation of an advertising slogan. But despite intense corporate pushback, fair use laws have successfully protected the work of artists, filmmakers, musicians and writers who poke fun at corporate brands, marketing campaigns and assorted non-trademarked sacred cows.

There are a few different tests a judge can employ when considering a trademark infringement suit. In this case, the justices relied on what’s come to be known as the Rogers test.

The Rogers test dates back to 1989, when Hollywood legend and Fred Astaire’s dance partner Ginger Rogers sued to block the release of Federico Fellini’s “Ginger and Fred” arguing that the Italian director’s use of her name and character constituted trademark infringement. She lost the case, but the decision established a two-tier test to determine if legitimate infringement has occurred. First, whether “use of another’s trademark in an expressive work has some artistic relevance to the underlying work.” Second, whether the use “explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.” In short, parody remains protected speech as long as the artist isn’t trying to trick people into believing the parody is the real thing. It’s a test that certainly seems to hold up in the VIP dog toy case, given the lack of any evidence the company set out to bamboozle illiterate drunks with dog poop groaners.

Nonetheless, on June 8, the Roberts Court returned with a 9-0 ruling in Jack Daniels’ favor. In the unanimous opinion, liberal Associate Justice Elena Kagan wrote, “it is not appropriate when the accused infringer has used a trademark to designate the source of its own goods — in other words, has used a trademark as a trademark. That kind of use falls within the heartland of trademark law, and does not receive special First Amendment protection.”

The court’s redefinition of what qualifies for First Amendment protection sets an extremely troubling precedent when it comes to the future of parody as a form. From Aristophanes poking fun at Socrates in The Clouds, to MAD magazine, National Lampoon, SNL, the Wayans Brothers’ movies, Garbage Pail Kids and even Philadelphia’s Mummers Parade, parody has always been a culturally therapeutic means of deflating self-important, bloated and humorless politicians, celebrities, corporations and products. Parody allows those who don’t have money or power to come together and make fun of those who do, to bring them down to our level. It’s one of the fundamental tools of free speech. It’s traditionally been a safety valve, the freedom to use art and humor to publicly mock people, things and institutions we find dangerous, ridiculous or just plain annoying.

We seemed to understand this when I was a kid, when parody-as-free speech was embodied in every corner store in the form of Wacky Packages, a sticker series that lampooned popular consumer products. Launched by the Topp’s trading card company in 1967, and drawn by several noted underground cartoonists, including future Pulitzer Prize winner Art Spiegelman, Wacky Packages featured wickedly subversive brand-spoofs like “Moron Salt,” “Free Toes,” “Ratz Crackers” and “Crust toothpaste.” By the mid-1970s, the stickers were outselling baseball and football cards.

Shortly after the series was launched, Topp’s was compelled to withdraw some of the stickers after lawyers from a few of the parodied companies sent cease and desist letters. But none of the cases went to court. As Wacky Packages grew in popularity, the threatened lawsuits evaporated. Being the subject of a Wacky Packages send-up became a point of pride, much like having a song spoofed by “Weird Al” Yankovic. “Bad Spaniels” was in essence a Wacky Package in chew toy form.

This decision forces us to confront the possible criminalization of parody, of our right to flip off iconic and humorless corporations with a few icons of our own.

It’s difficult to determine precisely when we experienced a shift in attitude, when harmless jokes not only stopped being funny, but became actionable in corporate eyes. For all the thousands of trademark infringement suits filed since fair use laws went into effect, the Bad Spaniels suit is the first parody case that has been brought before the high court.

“The ruling doesn’t make any sense, especially a nine-zero decision,” New York-based copyright attorney Kenneth Swezey says of Jack Daniel’s v. VIP. “I mean, if Jack Daniel’s was selling their own dog toys — and that may not be a bad idea — then that would make sense. But they’re not. Here’s what I think happened. In the Rogers case I suspect the judges were smart enough to know who Federico Fellini was, and said, ‘Well it’s Fellini, so of course that’s okay.’ But since then the parameters of fair use protections have grown broader and broader and broader. The Court’s been looking for a long time for a way to curtail that, set a strict limit, to say ‘okay that’s far enough,’ and this was their chance.”

With free speech under attack at every turn in recent years, and the term “free speech” itself now saddled with MAGA connotations, it was perhaps inevitable that parody would become a target in a world fast losing its sense of humor. Shortly after the 2016 election, my literary agent contacted me and the rest of her clients, asking that we stop writing fiction for a while. We had entered the Post-Satirical Age, she said, and nothing we made up could top the insanity of the real world. That was a mere suggestion based on the social climate. While it could be argued that the world today is a grand send up of itself, this decision forces us to confront the possible criminalization of parody, of our right to flip off iconic and humorless corporations with a few icons of our own. With this new precedent in place, any wiseacre parodist who dares make sport of Procter & Gamble, Apple or Facebook can now be crushed like a bug with the Court’s blessing.

Topp’s is still producing Wacky Packages, but my fear, and my guess, is not for long.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You know you live in a tyranny when it's illegal or tortious to have a sense of humor.