The U.S.-Mexico Trade War Over Modified Corn Heats Up

A new government in Mexico has pledged to carry on the fight to keep genetically modified corn out of the national diet. New President Claudia Sheinbaum waves to women holding corn stalks during a ceremony in the Zocalo, Mexico City's main square, on her inauguration day, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Fernando Llano)

New President Claudia Sheinbaum waves to women holding corn stalks during a ceremony in the Zocalo, Mexico City's main square, on her inauguration day, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Fernando Llano)

If the U.S. government was hoping a new president would weaken Mexico’s resolve to ban the cultivation and consumption of genetically modified corn, those hopes have been dashed.

“We will not allow the cultivation of genetically modified corn,” Claudia Scheinbaum stated in her inauguration speech on Oct. 1.

Mexico’s stand against GM corn — first expressed in a February 2023 presidential decree by outgoing president Andrés Manuel López Obrador — has become the source of a historic trade conflict between the United States and its largest trading partner. In August 2023, Washington’s trade representative responded with a formal complaint under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement (USMCA) that argued Mexico’s restrictions — aimed at keeping GM corn out of tortillas and other corn products for human consumption — were not based on science. After a year of formal back-and-forth filings before a trade tribunal, the three arbitrators are expected to issue a ruling in November.

Can the USMCA be used to undermine domestic policies for public health and the environment, even when they barely affect trade?

Mexico’s resolve — reaffirmed by Scheinbaum’s newly seated secretary of agriculture in his own inaugural remarks — presents a bold challenge not only to the U.S. government, but to a global trade regime widely charged with favoring multinational firms over countries’ legal commitments to protect public health and the environment. Mexico has argued persuasively that its precautionary GM corn policies are backed by a wealth of scientific evidence showing that high levels of consumption pose health risks from both GM corn and the herbicide residues that come with it. Since the measures scarcely affect the $5 billion in U.S. corn exports to Mexico used overwhelmingly as animal feed, Mexico’s challenge is simple and direct: Can the USMCA be used to undermine domestic policies for public health and the environment, even when they barely affect trade?

Where is the trade violation?

The U.S. case has been shaky from the start. Although the USMCA (the successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA) sports a new industry-friendly section on agricultural biotechnology, the text in no way obligates Mexico to accept U.S. biotech products it deems unsafe. In fact, the agreement explicitly allows for precautionary policies for public health and the environment, according to an analysis by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

Nor have Mexico’s restrictions significantly impacted U.S. corn exports. In the year-and-a-half since the presidential decree, exports have surged. Why? Because Mexican production was reduced due to drought so demand was higher, and — as Mexico keeps reminding us — there was no restriction on the overwhelmingly GM varieties of yellow corn that make up 97% of U.S. corn exports to Mexico. Last year, a record $5.3 billion in U.S. corn flowed into Mexico.

Nor is there evidence of a significant decline in white corn exports as a result of the decree, according to Mexico’s filings. Mexico did not restrict imports of GM corn for its tortilla industry, which is almost completely supplied by Mexican producers prohibited from planting GM corn. It restricted the use of GM corn, from any country, in the sector that produces tortillas and corn flour (masa). The borders remain open to U.S. white corn, even GM white corn; it just can’t be used in tortillas.

That may have reduced markets temporarily for a few U.S. exporters, accounting for at most 1% of exported corn. But they still have the option of producing non-GM white corn and retaining their Mexican markets.

At no point in the trade dispute has the U.S. government presented evidence that Mexico’s restrictions have reduced U.S. corn exports in any meaningful way. Mexico is certainly right to ask why its public health measures are being challenged under a trade agreement.

The emperor has no science

The crux of the U.S. case hinges on its assertion that the safety of GM crops is “settled science” proven by years of safe consumption in the United States and around the world. As U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack stated when the United States filed its complaint, “Mexico’s approach to biotechnology is not based on science.” The U.S. government challenged Mexico to prove otherwise.

Mexico has done just that. In its filings in the trade dispute, Mexico provided mountains of evidence from peer-reviewed literature that showed ample cause for concern about the risks of consuming GM corn and the residues of the herbicide glyphosate — most commonly known as Roundup — that often come with it.

The crux of the U.S. case hinges on its assertion that the safety of genetically modified crops is “settled science.”

Arguing that its residents eat more than 10 times the amount of corn as U.S. residents, Mexico flipped the burden of proof back on its northern neighbor. Pointing to a flawed U.S. regulatory process that relies on industry-funded studies of its own products and outdated scientific assessments, Mexico challenged the United States to show that its GM corn is safe to eat in the quantities and forms that Mexicans consume it.

As a Reuters headline put it in March: “Mexico waiting on US proof that GM corn is safe for its people.” No such proof was forthcoming as the U.S. government flailed in its attempts to counter the hundreds of studies Mexico identified that showed risk. A U.S. filing claiming to rebut the evidence did no such thing. The United States simply ignored some of the most recent science, such as studies in the journals Environmental Health Perspectives and Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology that showed worrisome kidney and liver ailments in adolescents after even low-level exposures to glyphosate. Other research suggested possible damage to the gastrointestinal tract in mammals from consuming the insecticidal varieties of GM corn, which kill insects by attacking their stomachs.

The failure to provide scientific evidence leaves the U.S. government exposed as Mexico has described it: insensitive, out of date and reliant on science corrupted by industry. On GM corn, the emperor has no science.

Reopening the debates over GM crops

With its public filings in the GM corn case, Mexico may reopen the debate in the United States and elsewhere over the safety of GM crops and their associated chemicals. Mexico’s national science agency, CONAHCYT, has compiled the most comprehensive assessment of the science based on its years of research. Much of that has been published and translated in the course of the trade dispute.

“CONAHCYT did an exhaustive review of the scientific literature,” said its outgoing director, Elena Álvarez Buylla, “and we concluded that the evidence was more than sufficient to restrict, out of precaution, the use of GM corn and its associated agro-chemical, glyphosate, in the country’s food supply chains.”

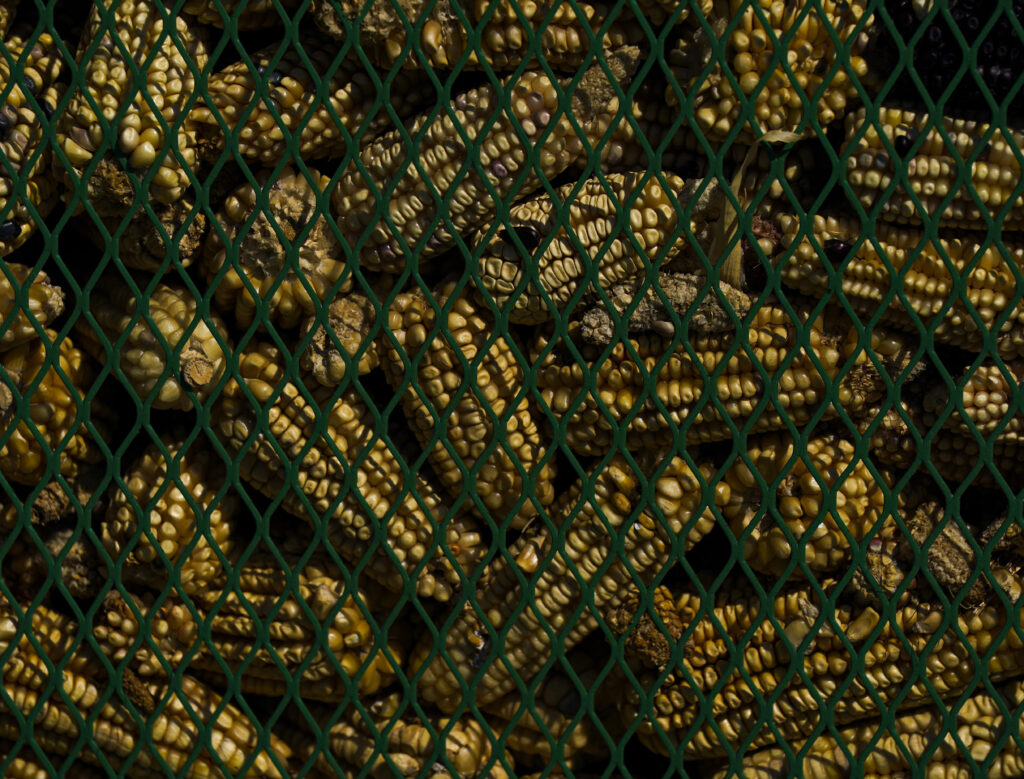

The science agency last week published the results of its monitoring of compliance with the GM corn restrictions. Its research showed the continued contamination of stockpiles of corn destined for the tortilla industry, with 25% of samples testing positive for the presence of transgenic traits and 39% for glyphosate residues. Calling the findings “worrisome,” the researchers called for labeling of GM corn to enhance compliance.

No one is going to force Mexicans to eat genetically modified corn tortillas laced with pesticide residues.

Sheinbaum faced pressure from Day One to change her predecessor’s stance. She was greeted on inauguration day by news of a letter from members of the U.S. Congress to the U.S. trade representative and secretary of agriculture exhorting them to demand that Sheinbaum back down.

Instead, Mexico’s Congress is doubling down. The legislature is set to pass a constitutional amendment banning the cultivation of GM corn and its use in tortillas and other common corn preparations, the very measures being disputed in the trade case. Sheinbaum’s Morena Party holds strong majorities in both houses of Congress and in most state legislatures, opening the door to constitutional reforms.

A controversial judicial reform requiring the popular election of all justices has captured the headlines, but the GM corn amendment is one of 18 constitutional measures submitted this year by López Obrador. The former president’s final shot across the bow in the trade dispute would give Mexico an additional legal weapon in its trade fight.

The message seems clear to U.S. officials and to the arbitrators: No one is going to force Mexicans to eat GM corn tortillas laced with pesticide residues. Mexican citizens have made their resolve known as well. In June, the coalition Sin Maiz No Hay Pais (Without Corn There Is No Country) sent more than 100,000 letters to the trade tribunal urging them to respect Mexico’s right to determine for itself how to feed its residents.

“A tribunal decision in favor of the United States would show that the trade agreement is nothing but an instrument for the U.S. to impose its will on Mexico,” says the coalition’s Tania Monserrat Téllez. “Regardless of the panel’s decision, Mexico must protect the health of its population and the biocultural heritage represented by our native corn.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.