The Forgotten Minority of the Occupied Territories

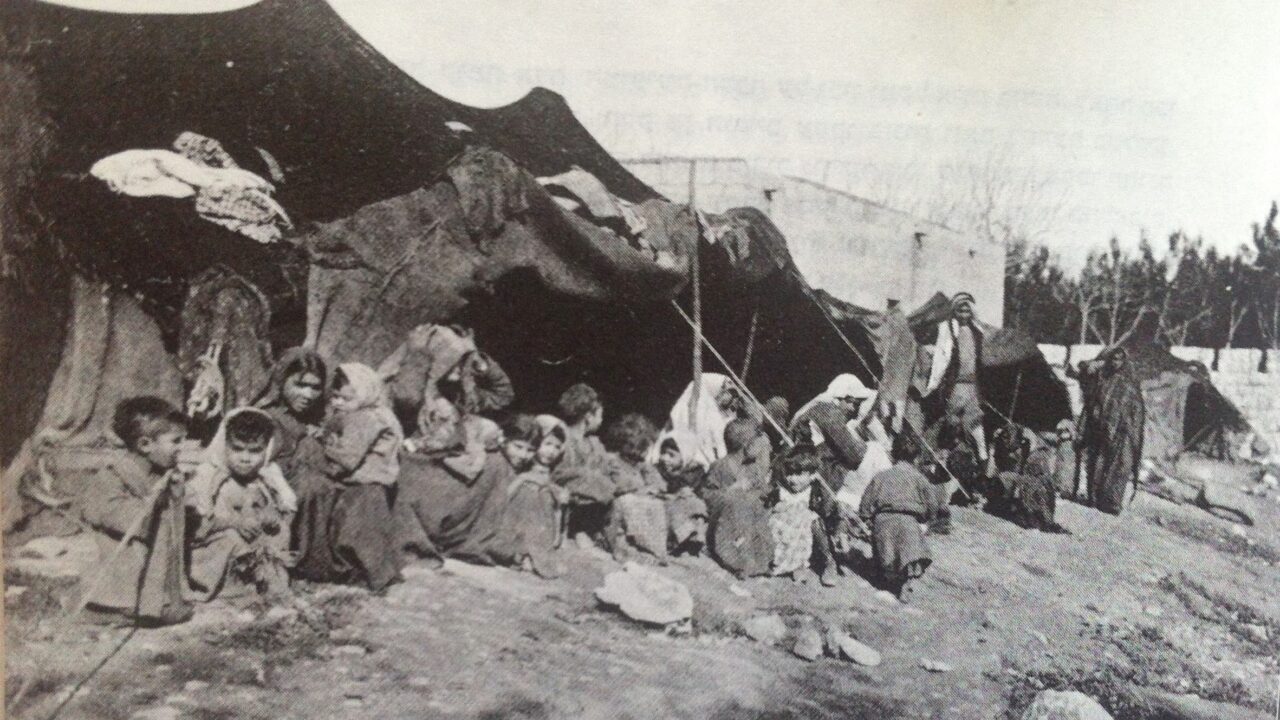

Amoun Sleem fights to give the minority Domari community of East Jerusalem pride and hope for a better future. A Domari encampment north of the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem in 1914 (Public domain)

A Domari encampment north of the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem in 1914 (Public domain)

At the heart of Occupied East Jerusalem, where religious and national tensions crisscross the streets like fault lines, resides a small community ignored by Israel and rejected by the Palestinians: the Domari. A relative to the Roma community in Europe, it is the most disenfranchised and underprivileged community in the Occupied Territories. Approximately 17,000 Domari suffer from racism, abject poverty, unemployment and high levels of illiteracy, along with all the social problems that thrive in these conditions, including violence and substance abuse. A traditionalist community, Domari women marry young, often in an arranged marriage before the age of 18, and frequently suffer domestic abuse.

One woman, though, has made it her life’s mission to change that. Amoun Sleem resolved at a young age to work to banish shame and prejudice and transform Domari heritage into a source of pride. In 2007, she created a community center where the culture is celebrated and after-school programs and job training are offered. She has become the single-most powerful force for change among the Domari.

Amoun Sleem spoke to Truthdig in January from her office in East Jerusalem.

TD: Before we start talking about the Domari community and your work, let’s talk for a moment about the situation in Israel/Palestine, where the ceasefire is holding for the time being. What is the feeling in the Domari community regarding this development?

Amoun Sleem: Honestly, for the first time in my life, I can feel that everyone, whether in the Domari neighborhood or the rest of the Old City agrees on one thing: They want this war to end. Because of the suffering of the people in Gaza. Even on the Jewish side, you can feel that everyone’s not okay, that this war has lasted too long.

TD: Do you have news from the Domari community in Gaza?

AS: The biggest Domari community in the Middle East lives in Gaza — around 12,000-15,000 people were living there when the war started. Everyone there is in the same boat. They are an integral part of the Gazan population. But we don’t know who’s alive and who died, how many were killed — we have no idea.

TD: Most people don’t even know that there’s a Domari community in Jerusalem. Can you talk about it?

AS: This is one of the main problems. Even the locals here, if you ask them if there are gypsies here, they don’t know. But this community has been living here now for more than 200 years. We are a few thousand people who live in Jerusalem and around it. Originally, they came from India, and then they spread around the world. Many came to the Holy Land. There were a couple of thousands who lived in small communities around and inside Jerusalem. During the Six-Day War in 1967, many Domari ran away. They now live in Jordan, calling themselves Palestinian gypsies, or refugees. They hoped they’d be able to get back to their homes, but after four days, the border was closed between Israel and Jordan, and they remained there. The ones who stayed behind settled in the Old City.

TD: Can you tell us a bit about the challenges the Domari community is facing?

“This community has been living here now for more than 200 years.”

AS: One of our biggest challenges is the lack of consideration for us as a minority. We are seen as a part of the Arab community, but our own sense of community is missing. It should be important to us to recognize we are a distinct minority here. It gives you status, it gives you a kind of identity, something to belong to.

TD: How does the Domari community get along with the Palestinian population?

AS: We have been living among them for many, many years. We grew up among them, they are our neighbors, and we consider ourselves as part of their society. The Domari speak Arabic, they don’t speak Domari. Some people discriminate against us. They consider us an inferior culture, and that makes us very angry. We are also a part of this land. Our culture [is] one of the cultures that belongs in the Old City. But when you feel like you are being denied, it puts you down.

TD: How does the Israeli administration treat you?

AS: We are part of the Palestinian community, and that’s how the Israelis view us. I don’t get any special treatment when I enter the checkpoints. I wait in line like all the Palestinians.

TD: How old were you when you decided to start your organization?

AS: Very young. I was 17. It was a stupid desire or decision, I sometimes think. I didn’t really get to live my teenage life. I jumped into something bigger than me. But now I can see the fruit of it. I see that people know us more as a community, people know our society better. The young generation has also changed a lot. They get a better education, and several young people have even become lawyers, teachers and nurses. If I look back 20 years and compare our situation to what it is now, I can see the difference.

TD: Can you tell me why you wanted to do this?

AS: My childhood was not easy. I felt all the time that I was being pointed at, that I was different from the other children. In this way, you really learn the meaning of discrimination — you feel like you are rejected and denied, simply because of your background. I wanted to change this pain into something positive so that people can get to know this community.

TD: How did that go? Because you left school at an early age, right?

AS: I was 10 years old, maybe 11. I stopped going to school because of the discrimination I experienced, whether from the teachers or the other students. When you have no friends and the teacher is against you, it makes you retreat from that space. The teachers were very rude to the Domari children. They punished us, shouted at us in front of the other children and pointed fingers at us. I felt that place was killing me, not helping me. So, I left.

“I stopped going to school because of the discrimination I experienced.”

Then I saw that, being unable to read and write, I couldn’t do much. I didn’t want to be like the older generations. My father was illiterate. I thought, if I go back, I can really find my way.

It was very difficult because no one could give me any support, like we offer kids through our organization with our after-school program. But in my home, at that time, no one was able to help me.

TD: So how does a 17-year-old find the inspiration and the strength to tackle the problems a whole community is facing?

AS: I hoped to be the first woman in the community who would bring about change and who would break the mold of women in this society. No one believed in me, as a woman, but I was full of energy. Still, the beginning was difficult. I had no money or support. It took a few years till I was able to start as an NGO.

TD: What was your goal at the time? What did you want to change, exactly?

AS: My ideas were very simple, like a child’s or a teenager’s. I wanted people to change their view of gypsies. Everyone was telling us we were bad, misjudging us. I wanted them to realize we aren’t bad or dirty, as they say. I was living in a very poor house, but it was always very clean. I grew up in a family that harbored no hatred toward anyone. They taught us love, not anger. So what’s wrong with this culture?

TD: How did you manage to create the center? How did you find the funds?

AS: It took seven years from the moment I registered the organization until I found the location and the people to support me. In the beginning, I got support from the Dom Research Center [an American organization that promotes Dom culture], and in particular from its founder and executive director, Allen Williams. My family supported me. God sent me different kinds of supporters, who helped me move forward.

TD: Tell us about the work you do at the center.

AS: For the past 10 years, we’ve been focusing on children and women. We have an after-school program with teachers who can really push children forward with their studies if they have problems in Arabic, English or math to give children the tools that will prevent them from dropping out of school. We recently hired our first Domari teachers.

For women, we focus mainly on professional skills. We know that many women marry at a young age. They don’t finish school, so we offer training programs, like hairdressing classes, beauty treatments, catering services and sewing courses.

“I wanted people to change their view of gypsies.”

I focus on women because I feel that women are the ones who can be key to the development of their families. The men in the community are slow to evolve, and many of them don’t work. There’s also an alcohol problem and issues with drug abuse. So, I try to first build confidence within the women. From that confidence can the financial independence grow.

That’s why all the courses we give can build women up economically. If you say, OK, we want to help you gain literacy — it can take years to build. We don’t want to waste her self-confidence. Instead, we try to give them something that will help them feel important. Once they get a salary, with which they can help themselves and their families, you raise their situation. They realize that with [paid employment] they can make a change.

TD: Do you see a change in the younger generation?

AS: I see changes, yes. I notice they realize that education is very important. Before, the number of dropouts was huge, but now it has improved. And it’s been helpful for the community. They even become envious of each other — when they see someone succeed, the other kids want to be like him or her.

TD: What are your wishes for 2025?

AS: If the world is OK, you are OK. My first wish is for this land. Whatever bad things happen here, they influence me, and they influence my family and my community. Maybe we can finally have a year of “rest,” without a new crisis. We need the conditions that will allow us to feel peaceful within ourselves.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.