Animal Harm

We have witnessed, in this film, a prolonged study in animal abuse I think Terrace is the worst kind of sadist—the unknowing kind—and I think this very good film provides a record of “science” at its most useless .

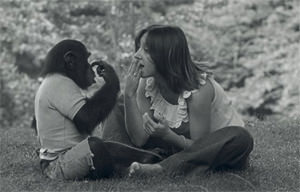

In 1973, a Columbia University behavioral psychologist named Herbert Terrace had this idea: Suppose you raised a chimpanzee in conditions as close as possible to those of a human baby, in the process attempting to teach him to communicate with his “family” by the use of sign language. Terrace’s notion was that, if successful, the barriers between man and his closest animal relative would be broken. Just possibly, a redefinition of what it means to be “human” would be achieved.

So a baby animal was acquired—and named “Nim Chimpsky” (that play on the name of Noam Chomsky represents academic humor at its lamest)—and, sure enough, the sweet little creature quite quickly acquires more than a hundred signs by which he can communicate his needs and desires to the humans with whom he is cohabiting. What this actually means in terms of the grand design underlying this project is unclear to me. It seems to me that what Nim is actually being taught is more in the nature of a circus trick than a serious scientific endeavor. “Aw, isn’t that cute.”

But never mind that for the moment. The thing that Terrace didn’t factor into his design was simple—namely that chimps rather quickly grow up into quite large animals that don’t entirely understand the difference between playing around and more menacing sorts of behavior. I guess someone like Terrace would say that they never achieve full-scale “socialization.” Putting it another way, you can take a certain amount of the animal out of the creature, but not all of it.

In director James Marsh’s documentary “Project Nim,” our sympathy flows naturally to the variously tormented ape. He seems to be a fundamentally good-natured fellow, and one earnestly attempting to ingratiate himself with the individuals who work with him. But let’s face it, he is, at base, a creature of the wild—one that can be taught tricks (like those circus seals that can play little tunes on an assortment of horns)—but not the subtleties of human interaction. At the end of the day, what he is responding to is what all animals respond to: a primitive system of rewards and punishments of the “good dog, bad dog” variety. These, I’m convinced, do not in any way address that redefinition of humanity that Terrace, at his most grandiose, sought to establish.

Marsh, who also directed the highly regarded “Man on Wire” documentary, understands this, though he is too good a filmmaker to openly insist on the point. He presents his interviewees and his excellent historical footage to tell this story objectively, and he shows that Nim’s guardians are decent, well-meaning folks who genuinely like Nim and are inclined to cut him plenty of slack when his animal nature is ascendant.

But, in the end, this is a minor tragedy. Finally Nim has to be returned to the primate research center from whence he was abducted as a baby, where what we might call his “people skills” are of no use to him in relating to his own kind (none of whom he has ever encountered in the course of his life as a pseudo-human being) or in developing behaviors useful to him living in the wild. He is a sad and isolated creature who is luckily granted some kind of happy ending when a human friend, who wants nothing from him except a playful friendship, more or less adopts him.

We, in the audience, breathe a collective sigh of relief when that happens. But this fact remains: We have witnessed, in this film, a prolonged study in animal abuse. I think Terrace is the worst kind of sadist—the unknowing kind—and I think this very good film provides a record of “science” at its most useless. I don’t want to present myself as a fur-hugging animal rights activist. But Terrace and his well-meaning associates do succeed in humanizing Nim just enough so that we can sympathize with him in his many confusions, which rob him of his fundamental identity without providing him with a reliable replacement for it.

Marsh has said that Nim had a forgiving nature, which is a good thing. Without it, and had he been a little larger, he might well have been an angry and anguished King Kong, with which in its little, touching way, this film shares many values, while adding a grim critique of science arrogantly marching on into a very disturbing moral abyss.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.