How a 19th-Century Whaleship Can Save the ‘White Working Class’

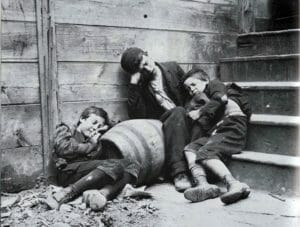

The story of the Essex—rooted in racialized ignorance and fear—offers a valuable lesson in survival for contemporary America. Whaling was a hazardous enterprise in the 19th century. (Wikimedia)

Whaling was a hazardous enterprise in the 19th century. (Wikimedia)

When I hear the phrase “white working class” (WWC), my mind turns to the tragic story of the Essex—an inspiration for Herman Melville’s famous novel “Moby-Dick” and a maritime tragedy as mythic in the 19th century as the sinking of the Titanic was in the next one. On Nov. 20, 1820, the Essex, a whaling ship from the Quaker island of Nantucket, Mass., was rammed by a giant white sperm whale in the remote depths of the South Pacific Ocean. Things did not go well for the captain, George Pollard, and his subordinates. As National Geographic explains:

There was nothing the crew could do—the animal was bigger, stronger, and had much, much greater agility than the ship. The ship sank within two days, leaving 20 survivors in three leaky whaleboats. … The survivors were more than 1,900 kilometers (1,200 miles) from the nearest islands (the Marquesas), without adequate supplies of food and freshwater. The boats were separated and most men resorted to cannibalism before being rescued months later. Of the 21 crew who left Nantucket, eight survived.

Nobody had heard of a whale turning the karmic tables on its human hunters and attacking a whaleship.

What were the whalers doing so far from home and land? Whaling had turned some of Nantucket’s leading Quaker families (including the Essex’s leading shareholders, Gideon Folger and Paul Macy) into millionaires. By 1820, however, New England whalers had diminished the Atlantic stock of their leading profit source, sperm whales. As National Geographic further explains:

Sperm whales, the species sought by the Essex and most other whalers of the time, were valued for both their blubber and waxy oil found in their huge heads. These substances were refined into oils that were used in candles, cosmetics, and lubricants for machinery. Whaling fleets had radically reduced sperm whale populations in the Atlantic Ocean, and the Essex had planned on a two-and-a-half year voyage to the rich “whaling grounds” of the South Pacific.

This was capitalism unbound on the high seas: Whaleship investors joined to the need of men without property (much of the Essex’s crew were unskilled casual laborers sent to Nantucket by Boston and New York City shipping agents) to rent out their only asset, their labor power. The sailors received a pittance at no small cost to life and limb on treacherous sea hunts that lasted for as many as three years. As Nathaniel Philbrick noted in his bestselling book “In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex” (2000), workers’ provisions were especially threadbare for those employed by Nantucket’s ship owners.

The island’s merchant-capitalist whaling masters were “famous for their ability to cut costs and increase profits.” Their Quakerism made them “pacifists” at home, but their wealth rested on bloody exterminist mayhem, danger (a quarter of Nantucket’s adult women were widows due to mishaps that regularly befell whaleship sailors), and ruthless labor exploitation abroad.

The National Geographic account leaves out three other critical and instructive parts of the Essex story. The first missing piece concerns an incident that took place on Charles Island, one of the glorious, species-rich Galapagos Islands. One month and five days prior to the ship’s sinking, Essex helmsman Thomas Chappel started a fire on the island while the crew scoured it for provisions. Chappel’s “prank” took place at the peak of the dry season, and the flames raged out of control. Even after a full day of sailing, the crew could still see the blaze on the eastern horizon.

Many years later, the Essex’s surviving cabin boy, Thomas Nickerson, returned to Charles Island. He found “a blackened wasteland,” wrote Philbrick, noting that “neither trees, shrubbery, nor grass have since appeared.” The fire contributed to the extinction of the Floreana Island tortoise and the near extinction of the Floreana mockingbird.

There’s an eerie karmic quality about the sinking of the Essex, inflicted after one of its crew members undertook the anthropogenic razing of an entire island. Don’t mess with Mother Nature.

A second missing piece, and here National Geographic’s omission is quite glaring, is the curious fact that all the Essex’s crew likely would have survived had they headed west with the winds to the relatively close Marquesas (1,200 miles away) or to any number of other human-inhabited Polynesian islands. The ship’s top three officers—Pollard, his first mate, Owen Chase, and his second mate, Matthew Joy—opted instead for a daunting eastward trek against the wind and across more than 2,500 miles, to Latin America.

Why this disastrous choice? A false rumor believed by the officers held that the South Pacific islands—including the Marquesas, Society and Tuamotu islands—were inhabited by fearsome, brown-skinned cannibals: warring, human-flesh-craving “savages.” Reasoning from racialized fear, the captain and his two mates calculated that their chances were better traveling over a much longer distance, with inadequate supplies and against the winds, for “civilized” and whiter Latin America.

This was a tragic mistake based on bad information. As the author Philbrick writes in his riveting account of the Essex tragedy:

Since before the turn of the [19th] century, China traders from the nearby ports of New York, Boston, and Salem had been making frequent stops at … the Marquesas [and] the Hawaiian Islands on their way to Canton. While rumors of cannibalism in the Marquesas were widespread, there was plenty of readily accessible information to the contrary. … [The Essex officers’] ignorance of the Society Islands, in particular Tahiti, is even more extraordinary. Since 1797, there had been a thriving English mission on the island. Tahiti’s huge royal mission chapel … was bigger than any [Nantucket] Quaker meeting house.

Years later, Herman Melville noted:

All the sufferings of these miserable men of the Essex might, in all human probability, have been avoided, had they, immediately after leaving the wreck, steered straight for Tahiti, from which they were not very distant at the time, & to which there was a favorable Trade wind. But they dreaded cannibals, & strange to tell knew not that it was entirely safe for the Mariner to touch at Tahiti. … They chose instead to stem a head wind, & make a passage of several thousand miles (an unavoidably roundabout one too) in order to gain a civilized harbor on the coast of South America.

Philbrick suggests that the Essex’s crew may also have been repelled by reports of “ritualized homosexual activity among the natives.”

Philbrick attributes the Essex’s rejection of the South Sea islands also to the fact that Nantucketers were known to be “suspicious of anything beyond their experience” and motivated by a “profound conservativism” and insularity. “If new information didn’t come to them from the lips of another Nantucketer, it was suspect.”

“By spurning the Society Islands and sailing for South America,” Philbrick adds, “the Essex officers chose to take their chances with an element they did know very well: the sea.”

In the end, ironically enough, the shipwreck’s survivors owed their endurance to cannibalism—their own, as they were forced to eat their own dead (one of whom was murdered by the lot).

The third missing part of the story has to do with North American black-white relations. Seven of the Essex’s sailors were black. None of these crew members were among the eight survivors. Five of the first six Essex crew members to die were black. The first four sailors to be devoured by their shipmates were black.

Philbrick ties this racially disparate outcome to the inferior diets of the black crew members—a reflection of racial discrimination in the United States. As Philbrick notes:

Black sailors who were delivered to the island [of Nantucket] as green hands were never regarded as equals. … It wasn’t lofty social ideals that brought Black sailors to this Quaker island, but rather the whale fishery’s insatiable and often exploitative hunger of labor. “[A]n African is treated like a brute by the officers of their ship,” reported the author William Comstock [after a stint on a Nantucket whaler]. “Should these pages fall into the hands of any of my colored brethren, let me advise them to fly [from] Nantucket as they would the Norway Maelstrom.”

… Nantucket whaling captains had a reputation as “Negro drivers.” Significantly, Nantucketers referred to the packets that delivered green hands [including a large number of Black laborers destine[d] for whaling duty] from New York City as “Slavers.”

Philbrick suggests that racism marked the black sailors as the least favored for the distribution of scarce resources among the shipwrecked group.

This is history that Nantucket was not keen to acknowledge. The island’s Quaker religion may have made white Nantucketers into formal (anti-slavery) abolitionists, but its capitalism, combined with its underlying racism, made its land and sea bosses into brutal “Negro drivers.”

The Essex tragedy strikes me as a hauntingly rich metaphor for much of U.S. social and political life today. Consider the following parallels.

A considerable segment of the American working class today is employed at no small risk to its health and safety in the rapacious extraction, processing, delivery and burning of the earth’s natural resources. The lion’s share of the profits made possible by this dangerous and “extractivist” toil goes to the disproportionately white investor class and not to the more multiracial wage earners who face hazards in and on coal mines, oil platforms, fishing boats, oil refineries, pipeline construction sites, fracking sites, grain elevators, lumber camps, oil tankers, trucks and trains, railway switching yards, and the like.

The fossil fuels that workers are paid (most poorly) to remove from forest, field, prairie, mountain, river, sea and seabed today are now cooking the climate beyond fitness for human habitation. The consequences of this mad-profit-addicted greenhouse gassing include epic droughts, massive floods, deadly heatwaves, record-setting hurricanes and giant wildfires (one drought- and wind-driven outburst just set a new fatality record in Northern California) that leave vast swaths of the planet looking like Charles Island when Thomas Nickerson revisited it: “a blackened wasteland.”

With livable ecology and hence a decent future now at ever graver risk, the earth is letting us know yet again that “nature bats last.” That’s what the giant sea mammal that rammed the Essex (the inspiration for Melville’s Great White Whale) told the world in its own way in the fall of 1820. Think Thomas Chappel’s burn power times 10 million on petro-capitalist steroids.

Species gone extinct because of reckless human behavior? We are in the middle of a Sixth Great Extinction, driven in no small part by U.S.-led global capitalism’s insatiable lust for unearthing and consuming natural wealth from the planetary commons.

American workers shipwrecked and left with leaky boats in a vast and unforgiving sea? Millions upon millions of U.S. working- and middle-class people have been pushed underwater (financially and otherwise) by low wages, joblessness, technical displacement, globalization, de-unionization and more in the neoliberal era. The opioid crisis that is wreaking havoc across much of the nation’s postindustrial “heartland” is a terrible reflection of this great marooning. Joined to related epidemics of alcoholism, gun violence and suicide, it contributes to a remarkable and unprecedented development—a decline in WWC life spans, driven by “deaths of despair” among precariously situated “surplus Americans” adrift in a vast ocean of capitalism-imposed nothingness.

Just three years before Melville published “Moby-Dick,” a 30-year-old communist philosopher named Karl Marx noted how the bourgeois system had “left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment.’ ” He famously observed: “It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom—Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.”

The ocean-tossed proletarians on the whaleships of the early and mid-19th century knew a thing or two about the “naked, shameless, direct, and brutal exploitation” that lurked beneath “the single unconscionable freedom” of “free trade” and the myth of bourgeois democracy (a veil for the unelected dictatorship of capital). In a similar vein, the displaced factory workers of the U.S. Rust Belt and other members of the American proletariat/precariat can tell you much unpleasant news about what happens to property-less people in a capital-globalized “free trade” world that “resolve[s] personal worth into exchange value.”

Disproportionate misery for black Americans veiled by political illusions of racial equality and benevolence? For all the hand-wringing about rising WWC mortality, black, Latino and Native American death, disease, joblessness and poverty rates remain considerably higher than those of U.S. whites. This gap reflects racial disparities that are deeply embedded across the nation’s core social structures and leading institutions. Blacks and Latinos provide the critical raw material for the history’s greatest mass incarceration system (the U.S. is home to 4.4 percent of the world’s population but 22 percent of its prisoners). The nation’s giant U.S. prison-industrial complex’s captives are more than two-thirds nonwhite.

The special oppression experienced by the nonwhite working and lower classes elicits remarkably little interest and attention in a white-majority political culture that is understandably shocked to hear that members of the WWC are dying younger than before.

The WWC is routinely and absurdly blamed for the right-wing and racist Donald Trump presidency. In fact, however, Trump’s backers have tended to be relatively well-off and not particularly working class. The racist, white-identitarian Trump coalition is a cross-class Caucasian phenomenon tilted more to the top than the bottom of the white class structure. The WWC didn’t elect Trump any more than all the white sailors on the Essex chose to head to Chile instead of Tahiti. That fateful decision was made exclusively by the ship’s white captain and his two best-paid white overseers. The 11 white crew members without officer status had nothing to say about it.

And why is the American working class so commonly seen as “white” these days? Seven of the Essex’s 21 crew members were black. In a similar vein, people of color make up a third of the U.S. workforce today. There is a “white working class” just as there is a “black working class” or a “Latino working class,” but the working class itself is multiracial and considerably less white than commonly advertised in the Age of Trump.

The poverty-stricken and addiction-plagued ghettos, barrios, reservations and trailer parks, and the hollowed-out former mill, mine, farm and factory towns of the United States stand as great monuments to the amoral system Marx described 169 years ago. To fight this ecocidal profits system and its ruling class with any chance of success, the working-class majority must form social and political movements to restore the natural and social commons and force a radical downward redistribution of wealth and power. To achieve this, it must mix and combine forces beyond the nation’s powerful divisions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, religion/irreligion, age, neighborhood and ability/disability.

Sadly, however, much of the white U.S. majority is mired in various states of fear, ignorance, revulsion and resentment about the mostly nonwhite people with whom its needs to join hands (see my Truthdig essay “White Blindness and Denial Characterize U.S. Racial Attitudes at the End of the Obama Era”).

The Essex might have avoided its sufferings and saved all hands but for bad information and the deeply conservative and narrow-minded, inward-looking mindset that fueled its officers’ fear of, and revulsion against South Pacific “savages.” In a similar vein today in the U.S., persistent de facto racial apartheid combines with distorted narratives and images purveyed by corporate-managed, media-politics culture (and not just by Fox News and right-wing talk radio and websites) to induce much of white America to view nonwhites in profoundly insular, provincial and reactionary ways—with excessive and undue trepidation and hostility. This bad information and blinkered ignorance, fear and disgust prevents millions of U.S. Caucasians from acting to make a better world and advance their own interests—even, indeed, to save themselves. It prevents members of the WWC from securing their own well-being, which they cannot adequately do except in solidarity with workers of other races.

This is what zero-sum bourgeois identitarian anti-racists like Ta-Nehesi Coates fail to understand. Shaming white Americans for their stupid whiteness and lecturing them on their need to pay reparations and drop their white skin privilege (good luck telling a former factory worker who is struggling with diabetes and three months behind on her trailer-park fees how “privileged” she is) won’t get us very far when it comes to re-enlisting the WWC in the struggle for a better world. The real point to make to white workers is that they are killing themselves by failing to join in common struggle (in the spirit of the old CIO packinghouse union slogan “Black and White, Unite and Fight”) with their fellow workers of color, without whom they can never hope to prevail. As Asad Haider recently noted in a brilliant critique of Coates, “for the white people who are not owners of capital, white privilege is a poisoned bait.” So are the intimately related problems of white racial ignorance and fear.

Meanwhile, the very predominantly Caucasian masters of capitalist disaster, mainly headquartered in the U.S (as they have been since white Europe’s suicide between 1914 and 1945), are the great white Captain Ahabs of our time. They are leading Homo sapiens and countless other species over the cliff of hopes for a decent, democratic and sustainable future.

Melville’s “Moby-Dick,” inspired by the real-life story of the Essex and by his own time on a whaleship and in the Marquesas Islands, was a warning of sorts. As the historian George Fredrickson once wrote: “In the character of Ahab, the whaling captain who brings destruction on himself and his ship by the endless pursuit of the white whale, [Melville] symbolized—among other things—the danger facing a nation that was overreaching itself by indulging its pride and exalted sense of destiny with too little concern for the moral and practical consequences.”

Overreach indeed: Ask a reputable earth scientist about that problem today. We have a generation at most to unite across our racial and other social fears and divisions to take decisive collective action on behalf of what Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called near the end of his life “the real issue to be faced”—”the radical reconstruction of society itself”—before all we’re left with is trying to turn a poisoned planet upside down.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.