A Different Way to Remember Ingmar Bergman

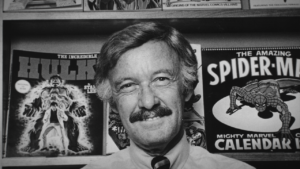

“Searching for Ingmar Bergman,” Margarethe von Trotta’s affectionate tribute, sets out to reveal the innermost secrets of perhaps the most guarded of film artists. Filmmaker Ingmar Bergman is captured on the other side of the camera in this image from the trailer for Margarethe von Trotta's "Searching for Ingmar Bergman." (YouTube)

Filmmaker Ingmar Bergman is captured on the other side of the camera in this image from the trailer for Margarethe von Trotta's "Searching for Ingmar Bergman." (YouTube)

Margarethe von Trotta’s “Searching for Ingmar Bergman” is affectionate, playful and at times passionate—all qualities one does not easily associate with Bergman’s films.

Von Trotta’s is one of two recent Bergman tribute films; the other, “Bergman—A Year in a Life” by Jane Magnusson, was shown at the Cannes Film Festival but has not been released in the U.S. Their timing coincides with the centenary of the great Swedish director’s birth. He died in 2007.

Bergman’s significance to 20th century cinema was cemented with films like “The Seventh Seal” (1957), “The Virgin Spring” (1960), “Persona” (1966), “Cries and Whispers” (1972) and many others familiar to critics, film students and art house patrons. Though everyone who follows cinema knows his name, Bergman’s presence has somewhat dimmed in this century, as even his greatest films have all but receded into the twilight realm of the praised but seldom seen.

What makes “Searching for Ingmar Bergman” come alive is that von Trotta helps us to see Bergman’s films as she first saw them, beginning with “The Seventh Seal” when she was 15. With a true filmmaker’s instinct, she opens her documentary walking on the beach where the protagonist crusader Max von Sydow awakens, and Bergman aficionados will be pleased to learn it scarcely looks any different some 60 years later.

“This is where it all began for me,” she recalls just as Bergman tells us that his love for film began when he first saw Victor Sjostrom’s 1921 “The Phantom Carriage,” which he claims to have watched at least once a year for the rest of his life. Von Trotta moves the film along at a leisurely gait that allows us to appreciate the reflections offered not only by Bergman but by other filmmakers, writers and actors such as Carlos Soura, Jean-Claude Carrière, Olivier Assayas, Mia Hansen-Love, Liv Ullman, Ingrid Thulin and Ruben Östlund. Conspicuously absent are Bergman’s most appreciative American fan, Woody Allen, and his most ardent critical defender, John Simon, the nonagenarian author of the 1972 book, “Ingmar Bergman Directs.”

Östlund tells viewers about the much-discussed rift between Bergman and the next generation of Swedish directors, who made less stylized, more naturalistic films. The fissure began with an infamous 1960 pamphlet written by Sweden’s second most famous director, Bo Widerberg, whose films, particularly “Elvira Madigan,” were more popular in that country than Bergman’s. (Bergman, it seems, was envious of Widerberg’s popularity.) Widerberg accused Bergman of artistic “stagnation” and having a “bourgeois sensibility.”

“What one expects with growing impatience from this brilliant technician and director of actors is for him to move on, to grow tired of his role as our Dala horse to the world,” Widerberg wrote. The reference is obscure to many non-Swedes; Dala horses are beautifully painted wooden toys.

Östlund seems to share this view, but most of the others who knew Bergman do not. Carrière, a screenwriter and critic, tells von Trotta that Bergman is “one of the phantoms who shaped the youth of our generation, who shape the New Wave.” Even, he adds, “if the New Wave took the opposite approach to him.” Though I wish von Trotta or Carrière had pursued this point, I assume he meant that while Bergman’s films helped free others to pursue their own paths, his work was too unique to produce disciples.

Von Trotta succeeds in showing us different, lighter aspects of a man whose work is indelibly associated with psychodrama. During a screening of “Pearl Harbor,” the Swede told the projectionist to skip the story and go straight to the action scenes. After so much immersion in Swedish film and German theater, Bergman, like so many of us, needed a cheap thrill.

The range of his favorite films extended from Carl Dreyer’s “Day of Wrath” (he thought of Dreyer as “the grand master”) to Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard.” He enjoyed watching soap operas and TV melodramas; one yearns to know what he thought about “Scenes From a Marriage” being an influence on the potboiler American TV series “Dallas.”

While these details humanize him, the more we learn about the director’s life outside film and theater, the colder he seems. In a jolting revelation, his son Daniel, himself a film director, tells us with an impassive face, “Since he died, I never once missed him. Not for a minute.” Daniel directed the 1992 film “Sunday’s Children,” for which his father wrote the script.

One of the most incisive comments on Bergman’s films comes from von Trotta, who tells us, “He looked to his own childhood more than that of his children.” Daniel nods, “Absolutely.”

As it turns out, he literally rewrote his childhood in his 1983 three hours-plus epic, “Fanny and Alexander,” one of three films to win him an Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. It’s one of the easiest Bergman films to enjoy, though Pauline Kael wrote, correctly, I think, “The conventionality of the thinking in the film is rather shocking. It’s as if Bergman’s neuroses had been tormenting him for so long that he cut them off and went sprinting back to Victorian health and domesticity.” In real life, Bergman’s father, a strict Lutheran minister, locked him in a closet overnight for wetting the bed.

“You shouldn’t trust Ingmar’s stories,” Daniel tells us with a wisp of a smile. French director and screenwriter Hansen-Love adds some perspective, proclaiming, “He never films children the way a father would.”

It’s disheartening to hear from the director of “Fanny and Alexander” that, after all, “The feeling of community is an illusion.”

Von Trotta includes a brief video of Bergman’s funeral on the island of Faro, off the southeastern coast of Sweden, where he had retired. He had planned his funeral and even had the coffin made. There were no flowers or eulogies, and only the local parson spoke. The guest list included a few actors, his family and everyone in the village.

“Searching for Ingmar Bergman” is gravid with tantalizing flashes of insight that promise to reveal the innermost secrets of perhaps the most guarded of film artists. Ultimately, those insights prove to be enigmatic rather than illuminating. “Film is a channeler,” Bergman says, “a distributor of dreamers and dreams.”

But what does that mean? To borrow the title from his 1961 film, it seems that Bergman only wanted to be perceived through a glass, darkly. He asks rhetorically, “Isn’t art to some extent always therapy for the artist?” Perhaps, but the real question is whether it’s therapy for the viewer.

It’s not von Trotta’s fault that such questions can never have an entirely satisfactory answer. Maybe that’s for the best—as Nietzsche said, “A thing that is explained ceases to concern us.” In some way I can’t quite explain, Bergman’s final act seems like a metaphor for his legacy. For many who love film, myself included, his work compels admiration without creating inspiration. Some of us just weren’t on that guest list.

I wonder how many who come across “Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey,” released in 1991, know that the scene in which the boys play Battleship with the Grim Reaper is a parody of the famous scene in “The Seventh Seal” in which Max von Sydow plays chess with Death? And how many still remember Bill and Ted?

Your support is crucial...

As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.