Alexander Hamilton Would Have Backed Trump’s Impeachment

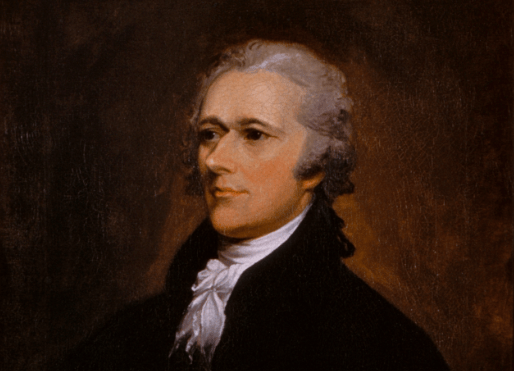

Both parties have invoked the founding father during Senate proceedings. Only one side is telling the truth about what he truly believed. A portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull. (Wikimedia Commons)

A portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull. (Wikimedia Commons)

Unless you’ve been in a deep coma or a lengthy, drug-induced stupor, you know that the House of Representatives has failed in its bid to remove President Trump from office on two articles of impeachment. The articles charged Trump with abuse of power and obstruction of Congress arising from his scheme to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to dig up dirt on Joe Biden in exchange for U.S. military aid.

You also know that the Republican-controlled Senate voted for the first time in the history of U.S. impeachments not to call a single witness to testify at Trump’s Senate trial.

One other thing you probably know is that, next to Trump and his former national security adviser, John Bolton, the name invoked most frequently during the Senate impeachment trial by both the Democratic managers and Trump’s defense team was Alexander Hamilton.

The frequent references to Hamilton were not surprising. Popularized as the title character in perhaps the greatest Broadway musical of all time, Hamilton in life was one of the primary framers of the Constitution. And among the framers, he was the most prolific writer on the topic of impeachment.

The invocation of Hamilton’s views on impeachment by both sides in Trump’s trial wasn’t just predictable; it was also entirely proper. Because the Constitution vests the House with the sole power of impeachment and the Senate with the sole power to try cases of impeachment, there is no “common law” of impeachment developed through court decisions. As the Supreme Court held in the 1993 case of Walter Nixon v. United States, in which a federal district court judge had been impeached for perjury, the issue of impeachment is a political question beyond the jurisdiction of the courts.

As a result, both sides in Trump’s trial resorted to “originalism” to explain the meaning that impeachment had for Hamilton and the Founding Fathers and, by extension, how it should be applied today.

First and foremost, Democrats and Republicans invoked Hamilton on the pivotal question of what constitutes an impeachable offense. The House managers, citing the lawyer, politician and economist, argued that impeachable offenses include abuses of power and are not limited to explicitly indictable crimes. Trump’s legal team argued the opposite. Trump’s lawyers also argued that Hamilton opposed what Trump’s team termed “purely partisan impeachments.”

As with many trials, one side got it right and one got it wrong. I won’t leave you guessing: The president’s legal team — including former Harvard professor Alan Dershowitz, who calls himself a liberal Democrat — invoked a Hamilton who never existed. The Democratic managers hewed largely to historical reality. The actual, real-life Hamilton was deeply concerned with abuse of power and tyrants in the mold of Trump.

As Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow explained in a Washington Post article published in October, the future first Treasury secretary warned as early as the Revolutionary War about the dangers of demagogues driven by ambition, greed and vanity. In a 1778 letter to the New York Journal attacking Samuel Chase, a delegate to the Continental Congress from Maryland who would later become a Supreme Court justice and be acquitted in an impeachment trial in 1805, Hamilton wrote: “When avarice takes the lead in a State, it is commonly the forerunner of its fall.”

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, he was a key participant in the debates about whether the new federal charter should include a provision authorizing the impeachment and removal of the president. Hamilton is widely credited with helping to break an impasse on the subject between proponents of the “Virginia Plan,” advocating for impeachment by the federal judiciary, and a “New Jersey Plan” that called for impeachment upon petition by a majority of state governors.

Hamilton urged instead that the convention adopt a plan modeled after British parliamentary practice, which had been in place for over 400 years at the time of the convention. In the British system (which has since become dormant), a lower legislative body (the House of Commons) promulgated articles of impeachment against government ministers in the fashion of a grand jury before an upper chamber (the House of Lords) adjudicated the articles in the fashion of a trial jury.

As initially introduced on June 18, 1787, Hamilton’s plan required “all officers of the United States to be liable to impeachment for mal-and corrupt conduct; and upon conviction to be removed from office.” Throughout the summer of that year, the framers refined the concept of impeachable offenses, finally settling the issue on Sept. 12, when they agreed on the now-famous clause inscribed in Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution: “The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

A fierce proponent of the new federal government, Hamilton took his defense of the Constitution and the impeachment power to the public in a series of newspaper essays — the 18th-century equivalent of today’s op-eds — that have come to be known as the Federalist Papers. Totaling 85 essays, Hamilton was the author of 51, with John Jay of New York and James Madison of Virginia penning the remainder.

Although Hamilton believed in a strong executive, he returned to the subject of tyranny raised in his 1778 letter in Federalist No. 1, urging his readers to be on guard against politicians of “dangerous ambition.” He also contended that “of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

Hamilton addressed the issue of impeachable offenses directly in Federalist No. 65. In the second paragraph of the essay, he made it abundantly clear that impeachment would encompass noncriminal conduct amounting to abuse of power:

“A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

Any doubt that Hamilton had in mind behavior that, strictly speaking, could be noncriminal was laid to rest in other sections of No. 65, in which he wrote that an impeachable offense “can never be tied down by such strict rules, either in the delineation of the offense by the prosecutors, or in the construction of it by the judges, as in common cases serve to limit the discretion of courts.”

Hamilton also stressed that impeachable offenses were not the same as ordinary crimes in Federalist No. 69, in which he wrote: “The President of the United States would be liable to be impeached, tried, and, upon conviction of treason, bribery, or other high crimes or misdemeanors, removed from office; and would afterwards be liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.”

Both the great weight of legal scholarship and subsequent impeachment practice have borne out his interpretation of high crimes and misdemeanors.

Including Trump, only 20 federal officials have been impeached in our history (President Nixon resigned before the full House voted on three articles of impeachment). According to the House’s procedural practice manual, “Less than one-third of all the articles the House has adopted have explicitly charged the violation of a criminal statute or used the word ‘criminal’ or ‘crime’ to describe the conduct alleged.”

Consistent with Hamilton, and contrary to the arguments of Trump’s counsel, the manual notes that whether dealing with presidents, judges or Cabinet secretaries, American impeachments “have commonly involved charges of misconduct incompatible with the official position of the office holder. This conduct falls into three broad categories: (1) abusing or exceeding the lawful powers of the office; (2) behaving officially or personally in a manner grossly incompatible with the office; and (3) using the power of the office for an improper purpose or for personal gain.”

Hamilton can’t be invoked for the proposition that impeachments must originate on a bipartisan basis in the House, either, as he recognized in Federalist No. 65 that they would invariably be partisan, writing: “The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused.”

Far from banning partisan impeachments, which he would have considered incompatible with the political character of the legal procedure and at odds with basic human nature, Hamilton argued in both Federalist No. 65 and No. 66 that the Senate, rather than the Supreme Court, would be best suited to try such cases. Only the Senate, in Hamilton’s view, commanded the respect required for such awesome undertakings. As he asked in No. 65:

“Where else than in the Senate could have been found a tribunal sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently independent? What other body would be likely to feel CONFIDENCE ENOUGH IN ITS OWN SITUATION, to preserve, unawed and uninfluenced, the necessary impartiality between an INDIVIDUAL accused, and the REPRESENTATIVES OF THE PEOPLE, HIS ACCUSERS?”

Hamilton returned again to the subject of tyranny in a different context, this time during the financial panic of 1792. In a letter to President Washington, he voiced concerns about populist resistance to federal tax policies and the leadership of local uprisings such as the Whiskey Rebellion that aimed to undermine America’s fledgling government:

“When a man unprincipled in private life desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents, having the advantage of military habits—despotic in his ordinary demeanour—known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty—when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity—to join in the cry of danger to liberty—to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion—to flatter and fall in with all the nonsense of the zealots of the day—It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may ‘ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.’ ”

I’m not a religious person by any means. But if I were, and if my faith permitted, I would bet every penny that Hamilton is spinning in his grave at the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in lower Manhattan at the mere thought of Trump’s acquittal.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.