Almighty

In 2012, a house painter, a Vietnam vet, and an 82-year-old nun broke into one of the most secure nuclear weapons facilities in the world with two bolt cutters and three hammers.

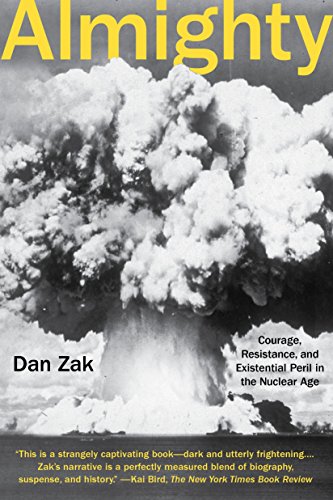

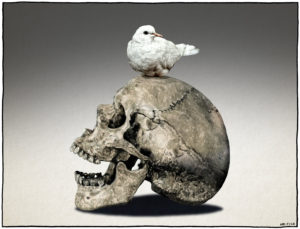

“Almighty: Courage, Resistance, and Existential Peril in the Nuclear Age” A book by Dan Zak To see long excerpts from “Almighty” at Google Books, click here.

On a September afternoon in 2010, a group of 200 activists descended upon the Y-12 nuclear weapons plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where more than 400 tons of highly enriched uranium was stored. As lines of police observed their every move, 14 protesters walked onto plant property, gathered in a circle and began to pray. In a development that surprised no one, they were promptly arrested for trespassing.

The protest marked the 30th anniversary of the “Plowshares Movement,” which had been launched when radical pacifists, including Catholic priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan, secretly entered a nuclear missile facility in Pennsylvania, hammered on a warhead cone and poured their blood on classified documents. But the post-9/11 world was a different place, and protecting nuclear facilities had become an urgent imperative. No longer could anyone — activist or terrorist — just stroll inside without being immediately detained.

“Y-12 is a very secure facility,” the building manager said during the trial of the 2010 trespassers. “It is, and will always be, one of the most secure facilities in this country and in the world.”

One of the people arrested in 2010 was Michael Walli, a Vietnam War veteran who spent more than a year in prison for the trespass. But on July 28, 2012, he was back in Oak Ridge, this time wearing a blue United Nations hard hat, communicating his status as an international weapons inspector of sorts. Accompanying Walli was Megan Rice, an 82-year-old nun with a heart condition, and Greg Boertje-Obed, a house painter from the Midwest. With Google Maps as their guide, the trio had hatched the unlikeliest of plans: break into the nuclear plant and hike a mile, over rough and hilly terrain, to Y-12’s Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility.

And yet there they were, at 4:29 a.m., already through the third and final fence. To penetrate one of the most secure facilities in the world had required a $25 bolt cutter from True Value. It wasn’t until they had hammered off chunks of the building, spray-painted numerous slogans and strung red tape — DANGER: NUCLEAR CRIME ZONE — that a security guard finally approached in a Chevy Tahoe, wondering what had triggered the alarm. Usually it was wildlife or the wind.

“Will you listen to our message?” the nun asked the disbelieving guard. Sensing the enormity of the security breach, he immediately radioed for backup. As the protesters were cuffed, they sang “This Little Light of Mine.”

The trio would later describe their action as a miracle, evidence that God had guided them along the way. The government considered it a catastrophe. In the hands of Dan Zak, author of “Almighty: Courage, Resistance, and Existential Peril in the Nuclear Age,” the episode also provides an opportunity to explore the dangers of nuclear weapons from an intimate perch. He weaves the drama of the break-in with a brisk history of the development of nuclear power and the resulting horrors. His sentences are spare, to the point and sometimes hard to forget. After cataloging the carnage that was visited upon Hiroshima, he observes that the city “had been erased by an amount of uranium that weighed no more than a human fetus at 28 weeks.”

The book has four characters: the three anti-nuclear activists, and the curious city of Oak Ridge. Located 30 minutes west of Knoxville, it had been erected virtually overnight in 1943, as the government raced to develop an atomic bomb. Tens of thousands of workers were brought in and given badges, which they needed to enter and exit the fenced off city. They put in 70-hour weeks, often only vaguely aware that their work was tied to national defense. (One group of Tennessee high school students was told they were making ice cream.)

In the spring of 1944, the Y-12 plant sent the first sample of enriched uranium to the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico. By Aug. 9, 1945, the uranium produced at Oak Ridge had made its way into a bomb dropped from the sky over Hiroshima. What came next is well known, but remains hard to comprehend:

The light from the explosion reached the Japanese first. Its blinding heat energy carbonized anyone within a half mile of ground zero. Thousands of pedestrians crumpled into crisp black husks. Birds in flight burst like fireworks. … If a Japanese citizen survived all that, he became his own ticking time bomb. His cells stopped dividing because of the intense dose of radiation, which meant organ decay, hemorrhage, and death in the hours and days afterward.

The atomic bomb had to be used, as I learned in high school, because it prevented the need for a ground invasion that would have cost up to a million American lives. But as Zak reminds the reader, that’s not at all certain. Even the U.S. War Department concluded that without the use of the atomic bomb, Japan would have likely surrendered before the date set for an invasion.Three days after Hiroshima, the harbor city of Nagasaki was hit. Afterward, one of the Marines sent to occupy Nagasaki was Walter Hooke, who spent five months bearing witness to uncensored carnage. Rice, the nun who broke into Y-12, was 16 when uncle Walter returned home. He had, as she later put it, “the terrible weight of knowing.”

It was a weight that Rice, who listened to his stories, would come to shoulder as well. She grew up in New York City, steeped in the progressive Catholic tradition. Her parents were friends with Dorothy Day, the radical founder of the Catholic Worker movement, which practiced voluntary poverty and service to the poor. Rice went to a high school run by an order of sisters whose motto was “action not words.” Before returning to the U.S. in 2003, she spent 40 years in Africa, where she taught children in rural villages without electricity, slept on the floor, and regularly contracted malaria and typhoid fever. In a broken world, privation was a form of comfort.

As one might imagine, each of the three activists has a rich and complicated background. Walli is clearly a haunted man, the scars of Vietnam written across his taut face in the book’s photos. Boertje-Obed, also a veteran, is gentler than Walli but no less militant. After being convicted for damaging a Navy aircraft in 1987, he went underground, only to surface atop the USS Iowa, hammering away at cruise-missile launchers.

The book draws much of its strength from Zak’s ability to present the trio with neither lionization nor ridicule. However one feels about breaking into nuclear facilities, it’s hard not to admire the bravery and sacrifice such acts require. It’s also impossible, as the break-in makes clear, to have faith in the ability of human beings to safely manage nuclear material. A week before the activists’ first court hearing, a laundry truck leaving Y-12 was discovered to be carrying 20 grams of highly enriched uranium, accidently left by a technician in his coveralls. And then there is Eric Schlosser’s 2013 book, “Command and Control,” a dizzying catalog of nuclear near-misses.

Yet as I made my way through “Almighty,” I began to question the heavy emphasis on symbolic acts that define the Plowshares movement. These are dramatic and heartfelt, but in some sense they amount to a retreat — from politics to political theater. In 1982, the nuclear freeze movement brought 1 million people to New York’s Central Park, which remains the largest political mobilization in American history. Today, a handful of hardcore activists risk everything to break into facilities and splash their blood on weapons, doing so as individual acts of conscience. Such incursions have done little to threaten the status quo or shift the debate.

Still, the activists bring a measure of hope and simple decency to a book that chronicles forgotten acts of barbarism. In 1946, a representative of the U.S. Navy met with inhabitants of the Bikini Atoll of the Marshall Islands. The Navy wanted to use the island to test nuclear bombs, a move it described as being “for the good of mankind” and that would “end all future wars.” The Bikinians agreed and relocated. Later, they asked when they would be able to return to their village. The military explained that it had been wiped off the map. Even the water and fish were contaminated.

“Oh,” the Bikinians’ interpreter said. “We’re very sorry to hear this.”

Over the next 12 years, the U.S. military ravaged the Marshall Islands with nuclear testing, dropping the equivalent of one and a half Hiroshima-sized bombs every single day. Future wars did not end, but a good-sized section of the planet was made uninhabitable. The challenge now, which “Almighty” makes feel both urgent and nearly impossible, is to somehow prevent us — this very flawed and very brilliant species — from unleashing such destructive power, either by design or accident, ever again.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.