American History for Truthdiggers: A Cruel, Costly and Anxious ‘Cold’ War

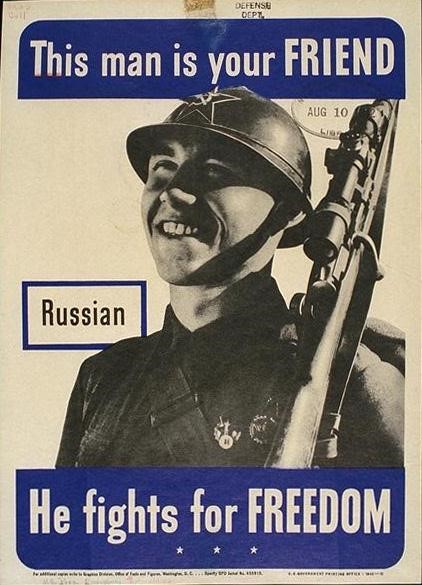

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. found a new enemy—its recent Soviet ally—and a new kind of conflict was born. Friends in war, enemies in peace: This 1942 pamphlet from the U.S. government reminded military personnel that the Soviets were part of America's wartime team. Not long after the shooting stopped, the relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union took a dark turn.

Friends in war, enemies in peace: This 1942 pamphlet from the U.S. government reminded military personnel that the Soviets were part of America's wartime team. Not long after the shooting stopped, the relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union took a dark turn.

Editor’s note: Below is the 27th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, who retired recently as a major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point.

Part 27 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23; Part 24; Part 25; Part 26.

* * *

Nothing is inevitable. Not war, not peace. Those writers and politicians who tell readers or constituents otherwise are selling snake oil. So it is, oftentimes, with proclamations about the Cold War. Americans have been taught, programmed even, to believe that a permanently bellicose nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union was inescapable—such was the diabolical nature of global communism. There were no alternatives, we have been told, to a firm military response to Soviet aggression in the wake of World War II. This myth of inevitability served, and serves, a vital purpose. That purpose is to explain the seemingly unexplainable: how Soviet Russia, America’s valued ally in World War II, so quickly transformed, almost overnight, into a national boogeyman. You’re not supposed to ask tough questions or draw nuanced conclusions; to wit: Weren’t the U.S. and the Soviet Union ideological enemies long before they were allies (of convenience)? And, couldn’t different American policies have assuaged Soviet fears and lessened the atmosphere of tense standoff after 1945? To answer yes to either, of course, is to commit national heresy, but honest history demands that the scholar and student do exactly that.

It is long past time for popular, digestible lay histories to re-examine the causes of the Cold War, to reassess the level of U.S. culpability in the outcome and to demonstrate the nefarious international and domestic effects of the resultant militarized standoff. Though far from inevitable—if probable—the Cold War remains highly prominent in U.S. history; not only because the world for more than four decades lived one press of the proverbial button away from nuclear annihilation, but because the country that Americans now inhabit—its government, military, foreign policy and shrinking liberties—was forged in the immediate postwar years.

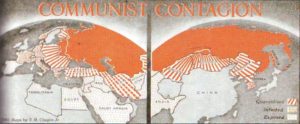

America’s foremost enemies have changed since World War II, but over time they have come full circle. There were the Russians, then the Russians/Chinese, then (after-1989) “terrorists” and Iraqis, and, today, the Russians and Chinese once more. The United States has never ceased, in the postwar era, to have an allegedly existential enemy. Such mortal foes serve a momentous purpose for governments. They focus and unite the populace in fear of the foreign “other” and distract from growing wealth disparity and deindustrialization. They foster trust in ostensibly informed intelligence and defense officials and draw the public gaze away from increasingly dissipating civil liberties. The ever-growing and all-embracing military-industrial complex demands—counts on—a combination of communal apathy and fear. Fervid consumerism and outward-looking trepidation are musts for the militarist welfare state to function.

It has long been so. Nonetheless, something profoundly changed in the aftermath of American triumph in the Second World War. The United States, until then mainly hesitant about overseas intervention and empire-building, became—and remains today—a globalist hegemon. In a sense, 1945 stands as the pivotal turning point in American foreign and domestic policy. The “sleeping giant” of North America woke and transformed into an ever-vigilant militarist colossus, dotting the earth with hundreds of its armed bases and ready to intervene anywhere, anytime, at a moment’s notice.

Seen in this light, rather than ushering in that which the common American GI of World War II had hoped for—an era of relative peace and tranquil prosperity—victory over Nazi Germany and imperial Japan only brought forth a new insecurity, new fears. In U.S. government rhetoric, and, to some extent, technical reality, the Soviet (and communist) behemoth loomed as an altogether more profound threat—one that could bring about the extinction of the human race. Be that as it may, few Americans saw then (or now) the ominous position that their government held in that apocalyptic reality: that one false move or misunderstanding by an American president could just as easily destroy mankind. As we rewind, then, to mid-1945, let us reassess, with fresh eyes, the role of the early Cold War and its effect upon the United States. Seen with clear vision, it makes for a hell of a story, one that ultimately is absurd.

Broke World, Rich America: 1945 in Retrospect

When Germany and later Japan surrendered, much of Europe, Asia and North Africa was in rubble. Societies had collapsed right along with the buildings; economies were devastated; tens of millions were dead. Only the United States, alone among industrialized powers, stood largely untouched. Its homeland unscathed, its casualties (relatively) light and its economy booming, America stood proudly and powerfully astride a broken world. Now the United States faced a monumental choice: How would it wield its unsurpassed strength now that the guns had (temporarily) fallen silent? The fate of a people, and a planet, rested on America’s fateful decision.

Wars, it turns out, are good for business, stimulating the domestic economy and generating something close to full employment. They are especially so when fought as away games, distant from the homeland, ensuring that all the downsides—death, destruction, psychological depression—occur elsewhere. In that sense, the Second World War was a boon for the U.S. economy, lifting the nation out of the Great Depression in a way that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s modest stimulus programs could not. Almost all of the rest of the world, however, was broke. That went for allies and enemies alike. American lend-lease aid had kept the partners of the U.S. afloat, but newly inaugurated President Harry Truman put an end to the program soon after Japan’s surrender. Both the Soviets and the British suffered. The Brits, humiliatingly, had to come to Uncle Sam with hat in hand for a $3.75 billion loan. Washington drove a hard bargain with its “special” ally, insisting that the cash be spent on American goods and that the British Empire be opened up for free trade with the U.S.

Still, rich though America was, many senior policymakers feared that with the end of the war the domestic economy might once again slide into depression. As a preventative, they decided, international markets would have to be found for America’s manufactured goods, including those of the booming weapons industry. In an unprecedented move, the State, War and Navy departments formed a committee in 1947 that concluded “it is inescapable that, under present programs and policies, the world will not be able to continue to buy United States exports at the 1946-47 rate.” America’s old ways—limited intervention and limited interaction with the rest of the world—would have to be altered. New markets for American defense and consumer goods would need to remain open during the coming “peace,” and, if necessary, U.S. cash would initially have to be infused into Europe to increase foreign purchasing power. Seen in this light, later loans and overseas grants—one thinks of the Marshall Plan—were as much about self-interest as humanitarianism.

Whether this was ultimately a tactical or a moral move, the fact remained that only the United States was capable, in the late 1940s, of such largesse. For all the later propaganda about the scope of the Soviet threat, the two sides’ wealth and economic potentials—the true measures of modern power—were never close. This was especially true in 1945, when the U.S., with just 7 percent of the world’s population, possessed 40 percent of global income, half the world’s manufacturing output and three-quarters of the world’s gold reserves. America also proved that it could field, supply and deploy a massive military—a real achievement considering that just seven years earlier the U.S. Army was smaller than that of Romania.

Fellow belligerents in the late war held an understandable resentment for the power and position of the pristine United States. After all, only 400,000 Americans (nearly all of them members of the military) died in a conflict that took 60 million lives worldwide. The country generally believed to have had the greatest loss of lives was the Soviet Union, which suffered more than 20 million military and civilian fatalities; in addition, it bore the brunt of the Nazi war machine (eight-tenths of Germans killed in the war died fighting Russians). After taking such blows, it saw its lend-lease aid cut off by the Americans almost as soon as the guns fell silent.

While the people of Europe and Asia scrounged and starved in the immediate aftermath of a devastating war, America’s consumer economy boomed. And, as tens of millions of foreign military veterans flooded into weakened domestic economies, the U.S. thanked its veterans with the generous GI Bill, financing higher education and low-interest home loans for countless demobilized service members. Though the cost of the GI Bill constituted 15 percent of the federal budget by 1948, it paid for itself 10 times over through increased future tax revenues. As the rest of the combatant countries struggled, America was building a new middle class. It was the envy of the world. How the U.S. would wield its new, unprecedented power remained to be seen.

Contested Origins: The Outbreak of Cold War in Myth and Memory

“Russians, like the Japanese, are essentially oriental in their thinking … and it seems doubtful that we should endeavor to buy their understanding and sympathy. We tried that once with Hitler. There are no returns on appeasement.” —Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal (1945)

The standard American tropes about the origins of the Cold War are so much malarkey, little more than comforting patriotic yarns designed to raise morale and bolster mythologies of American exceptionalism. Reality was far less simplistic than this propaganda. In truth, the United States and Soviet Russia shared responsibility for the outbreak and perpetuation of an unnecessary and highly dangerous Cold War. Analyzing this era, and parsing out fact from legend, requires holding two dissonant truths simultaneously: that Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was indeed a monster and mass murderer, yet at the same time he, and Russia, possessed justified fears and grievances with respect to an often aggressive United States.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, the massive Soviet armies were, by force of arms, ensconced in all the former sovereign nations of Eastern Europe. The Soviets had bled on a level unfathomable to an American to “liberate” all the territories east of the Elbe River in Germany from Nazi control. The British and Americans, by contrast, held France, the Low Countries and Italy, plus Germany west of the Elbe. These were the military realities on the ground, the tyranny of operational maps. As such, this situation set the stage for serious questions about the future boundaries of Europe, the degree of local sovereignty, and the economic systems that would prevail. While not inevitable, the Cold War does appear to have been likely given the seemingly binary division of Europe between two powerful but ideologically distinct allies, the Soviet Union and the United States.

Only look again; think bigger than comparisons of tank divisions and lines on the map. The United States was, despite its smaller army, much more powerful than its later Soviet foe. A generation of Russian men (and women) was dead, the country had been ravaged by the Nazi invaders, and the Soviet economic potential paled in comparison with that of the U.S. The Americans, by contrast, had (for a time) sole possession of atomic weaponry, control of nearly half the world’s economic resources, naval/air supremacy and a pristine homeland thousands of miles from the nearest Russian soldier and protected by two giant oceans. To paraphrase FDR, all that Americans had to fear, in this moment, was fear itself. Still, it appears that U.S. foreign policy elites craved fear, craved an enemy. Thus developed the traditional narrative that the Soviet army under the direction of “Crazy Joe” Stalin had intended to conquer Western Europe and, perhaps, the world. According to this notion, they, the “Asiatic” Russians, were to blame for kicking off the Cold War.

Before pressing on in this essay, it’s important to recognize that there is some truth in the standard, prevailing narrative. The Soviets, under Stalin, were deeply cynical. When “Uncle Joe” realized after Munich that the Western Allies were unlikely to stand up to Hitler, he cut a deal with the Nazis, signing a nonaggression pact with Hitler in 1939. Taking matters a step further, upon the outbreak of war, the Soviets gobbled up eastern Poland and the Baltic States and invaded Finland. This was blatant, opportunistic expansionism. Furthermore, since World War II officially started when Britain and France decided to fight Germany over its invasion of Poland, it might be said that the Soviet Union was a tacit enemy of the Allies at the outset of conflict. Stalin, terrified of what he saw as an impending war with the fascists, wanted friendly, docile buffer states on his western border. To cripple Polish nationalist opposition, Soviet troops were ordered to secretly execute thousands of Polish military officers and dispose of the bodies in the Katyn Forest. This war crime was the norm for a regime that murdered its own people, especially dissenters, as a matter of course.

Furthermore, after Stalin joined the Allies in reaction to being invaded by Nazi forces, he continued to operate duplicitously regarding Eastern European sovereignty as a whole and the Polish question in particular. At the Allies’ Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam conferences, despite agreeing to limited language of “sovereignty” and “elections,” Stalin made quite clear that he intended for the Soviets to maintain pre-eminence and a sphere of influence in the regions “liberated” from the Germans. Even President Roosevelt, who always held out hope that he could “deal with” Stalin and hold the wartime alliance together after the Axis countries surrendered, seemed, ultimately, to realize this. In March 1945, three weeks before his death on April 12 and less than six months before the war’s end, he complained privately, “We can’t do business with Stalin. He’s broken every one of the promises he made at Yalta.” Nonetheless, Roosevelt thought it imprudent to stop working with the Soviets, and we probably can never know how he would have proceeded if he had lived longer. One final point: There is no doubt that Stalin sought to maintain a powerful ground army and to prioritize the development of nuclear arms, submarines and long-range bombers after the war with the specific intent to strike at the U.S. homeland if necessary.

Still, we must now ask why. Why, that is, did Stalin and the Soviets operate as they did? The answer is security, not hegemony. Stalin’s Russia, though espousing a powerful evangelist communist ideology, operated much the same as czarist Russia had before the 1917 revolution. As such, the Soviets pursued powerful—but not unmanageable or hegemonic—foreign policy goals familiar even to 19th-century European observers: access to the Dardanelles Straits, a warm-water port for its navy and influence over the Iranian plateau on its southern border, as well as clout in and friendly states on its western border with Europe. Looking westward from a Soviet’s point of view, one can understand the obsession with “buffer states” in Eastern Europe. After all, much of Russia had been devastated by three invading armies—two German, one French—that spilled across its borders along that very axis of approach. Padding its western border with client, buffer states seemed good policy. Security, plain and simple, was the primary goal.

As for Poland, the two great powers viewed that beleaguered state quite differently. For Britain and the U.S. a democratic, sovereign Poland cohered with their global rhetoric and postwar preferences. However, their inclinations were far from existential. To Stalin, conversely, Poland was a “matter of life and death for the Soviet state.” It was, for Stalin, “a question of the security of the [Soviet] state, not only because we are on Poland’s frontier but also because throughout history Poland has always been a corridor for assaults on Russia.” Besides, Stalin could argue, hadn’t Roosevelt himself acquiesced to Russia’s predisposition? FDR had said, at Yalta, “I hope that I do not have to assure you that the U.S. will never lend its support in any way to … a government in Poland that would be inimical to your interests.” To Stalin that meant a friendly, and by definition communist, Poland. Besides, what leverage, ultimately, did the U.S. president have to change Poland’s already de facto status? Little to none.

Conquest, whether of the European continent or the entire globe, was beyond Russia’s reach or intent. After all, Stalin the paranoid megalomaniac was also a rational realist and a cool customer at the game of geopolitics. Some serious American policymakers ultimately knew this, including George Kennan, the pre-eminent U.S. diplomatic expert on the Soviets. As early as July 1946, Kennan explained that “[s]ecurity is probably their [the Soviets’] basic motive, but they are so anxious and suspicious about it that the objective results are much the same as if the motive were aggressive.” Here, Kennan accidentally summarized the problem set: The U.S. and the Soviet Union viewed the post-surrender world through two different lenses—that of a nation recently ravaged and invaded (Russia) and another largely untouched by what was ultimately an overseas intervention (America). Each side projected motives onto the other, and most Americans concluded that Soviet goals were nearly limitless. But Stalin knew, better than anyone else, the limits of Soviet power and potential. As a result, he would push only so far and no further. There was no serious consideration of conquest of Europe or global empire in the late 1940s. That fear, as is so often the case, was in Americans’ collective heads—projection rather than reality. It was to remain so for nigh on 50 years.

Until the late 1960s, even most academic historians bought the traditional Soviet-blaming narrative. However, as American culture shifted with the disaster of the Vietnam War, a new generation of scholars—“revisionists”—began analyzing American culpability in the early Cold War. Their argument built on the security-centric analysis above and argued that, at root, Soviet postwar policies were defensive rather than aggressive. After all, much of the Soviet Union had only recently been demolished, with 1,700 towns, 34,000 factories and 100,000 collective farms destroyed. The revisionist historians, including this author, drew further practical conclusions. For example, whereas Soviet-blamers decried FDR and Truman’s unwillingness to defend Eastern European sovereignty, a more prudent analyst questions exactly what the Americans could have done about that in 1945-46. Just as Western armies were in control of Western Europe, the many millions of Stalin’s soldiers claimed squatter’s rights in Eastern Europe. Short of a cataclysmic World War III, it’s unclear what leverage the U.S. and Britain had to change the facts on the ground.

Furthermore, the expanded Soviet sphere in Eastern Europe must be viewed in context; it was little different than U.S. dominance in the Caribbean and South and Central America. Why should the victorious and powerful Soviets not demand the kind of clout that America already had? What’s more, as we will see in more detail, Stalin proved far more flexible and cautious than most American leaders—then and now—were willing to admit. He had serious economic problems at home, and, though he was a publicly vocal proponent of worldwide communist revolution, he lent only limited support to burgeoning communist parties in the 1940s. He left rebellious Finland some autonomy, gave marginal aid to Greek communist rebels, put only intermittent pressure on Iran and Turkey (quickly backing down when pressed by the U.S. in 1946) and, most importantly, gave minimal military or moral support to Mao Zedong’s successful communist revolution in China.

Add to this Russian caution and elasticity the genuinely threatening U.S. policies that heightened Stalin’s fears. He simply never trusted the West, just as the West never truly trusted him. Throughout the war, Britain and the U.S. delayed opening a meaningful second front in France, despite Stalin’s pleas, and let millions of Soviets die in taking the brunt of the Nazi onslaught until the last 11 months of a six-year war. Then, immediately after the war, President Truman suddenly refused to extend loans and aid that the Soviets desperately needed. Indeed, American ships carrying aid were ordered to reverse course when they already were en route to Russia. Stalin called these actions “brutal,” executed in a “scornful and abrupt manner.” Such behavior furthered the Soviet view that the West harbored a capitalist plot to bankrupt and destroy the still relatively young communist state of Russia (then still the only such nation in the world!). Further feeding Stalin’s paranoia was the United States’ unwillingness—despite the pleas of Soviet diplomats and American scientists—to share nuclear secrets with its ostensible ally. This was most certainly read by Stalin’s conspiratorial mind as a not so surreptitious threat. Who can blame him?

One must conclude, then, that both sides bore some responsibility for the eruption of the Cold War–that misunderstanding and misinterpretation of each power’s respective motives contributed to the strife. Still, given the objective power imbalance between the two sides, the early U.S. nuclear monopoly, the facts and limitations on the ground, and legitimate Soviet security fears, it is the United States, primarily, that must bear the larger share of responsibility for early escalation of the Cold War. Even so, however, from the (often ignored) Polish perspective it is paradoxical—and tragic—that a war begun over the question of Polish sovereignty would end with that nation still in proverbial shackles. Only the occupier had changed. This stands as a disconcerting fact, one that turns the whole premise for World War II on its head, but there’s not much, in the end, that the West could have done to change this reality.

Such is the truth, and tragedy, of realism in foreign affairs. It remains so today. Many serious intellectuals saw this back then. Even the highly respected, and anti-communist, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr recognized the futility of American bellicosity or attempts to change the world as it was. In September 1946, Niebuhr wrote in The Nation that the U.S. should end its “futile efforts to change what cannot be changed in Eastern Europe, regarded by Russia as its strategic security belt.” Indeed, he continued, “Western efforts to change conditions in Poland, or in Bulgaria, for instance, will prove futile in any event, partly because the Russians are there and we aren’t. … Our copybook versions of democracy are frequently as obtuse as Russian dogmatism.” Finally, “If we left Russia alone … we might actually help, rather than hinder, the indigenous forces which resist its heavy hand.” This wisdom, essentially, defined the road not taken in the postwar years. Instead the U.S. became quickly determined in its reflexive anti-communism, and both sides settled down in their own armed camps. The result would be a world held hostage to the threat of nuclear annihilation for decades to come, and, in the end, none of the millions of “hot war” deaths in an era of “cold war” would ever change that reality. Nations, just as people, are capable of dying in vain.

American Action, Soviet Counteraction: The Early Cold War (1946-54)

One of the first major crises broke out in little Greece. It was here, oddly, that the United States would take its stand; here where an inexperienced, insecure President Truman would plant his anti-communist flag; where the U.S.—for better or worse—would self-consciously avoid another “Munich,” another “appeasement.” But was it the right place, and was it necessary? With hindsight, this appears unlikely. By 1946-47, Britain, a traditional protector of Greek independence, informed the U.S. that the British economy could no longer support military aid to the provisional capitalist government of Greece. The implication: The mighty USA should step in.

Yet the conflict in Greece was a civil war, and though there was a communist faction, Stalin actually did little to bolster that group. Besides, the right-wing government in place may have been notionally capitalist but it was also highly corrupt and monarchical. Indeed, a U.S. envoy to Greece returned to the States with the following conclusion: “There is really no state here in the Western concept. Rather we have a loose hierarchy of individualistic politicians, some worse than others, so preoccupied with their own struggle for power that they have no time, even assuming capacity, to develop economic policy.” He continued, claiming that Greek government activities were distinguished by “an almost complete deterioration of competence.” That Greek capitalist factions were superior to the communists was the big lie. Nonetheless, Truman—always crafting an image of toughness—decided to get the U.S. indirectly involved in the fight on the basis of that lie and granted $400 million in military aid to the Greek government, some 1 percent of the entire U.S. federal budget.

He went further still. Greece, Truman decided, would provide the model for future American interventionism. An obtuse, misguided report from the U.S. State, War and Navy departments had already concluded in apocalyptic terms that “[t]here is, at the present point in world history, a conflict between two ways of life [Western capitalist and Soviet communist].” Truman agreed—he liked simplistic heuristics—and developed a shallow sort of “domino theory” that if Greece fell to the communists, so too would Turkey, then France, and on and on. What the new president needed, he determined—perhaps to ensure his historic legacy—was a doctrine, a Truman doctrine. Such a credo must be brought to and sold to the American people, of course. To convince a populace weary of war, Sen. Arthur Vandenberg advised Truman, there was “only one way to get” what the president wanted: “That is to make a personal appearance before Congress and scare the hell out of the American people.” And so he would. Before a joint session of Congress, Truman would present an unsophisticated binary picture of the world. To achieve a peaceful world, “it must be the policy of the U.S. to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” He should have been more specific. After all, he meant Soviet outside pressures, not American compulsion, which continued as heartily as ever. Still, hypocrisy aside, most Americans bought his line—hook, line and sinker.

By taking over responsibility for stability and anti-communism in Greece from the British, the U.S., under Truman, invariably militarized a regional, actually local, ideological conflict and applied this model the world over. To do so was an American choice, an unnecessary one at that—and against the advice of George Kennan, the supposed architect of Cold War “containment” of Russia. Even as the government official and respected scholar of the Soviet Union decried the Russian danger, he always believed, according to historian James Patterson, that the “West should not overreact by building up huge stores of atomic weapons or making military moves that would provoke a highly suspicious Soviet state into counter-actions.” This, through the Truman doctrine and intervention in the Greek civil war, was exactly what the United States had done, and less than two years after the war in Europe had ended! The consequences were severe, ushering in an ever-escalating Cold War.

Truman had taken the United States on a wayward path for little, irrelevant, corrupt Greece, in the process overturning one of the most sacred and longstanding American traditions in international relations: non-entanglement in peacetime affairs of countries across the seas. This had been the policy, and philosophy, of George Washington, of Thomas Jefferson, yet Truman reversed 150 years of custom over Greece. From the Truman Doctrine, matters easily flowed on a course of peacetime military alliances—the very approach that had sleep-walked the nations of Europe into the cataclysmic First World War. So it was that in 1949, long before the Soviets (few remember this) crafted their own Warsaw Pact alliance, the United States signed onto the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the articles of which obligated America to rise to the defense of any allied partner, say … Belgium. This was profound, and traditionalists in the Senate, such as Robert Taft of Ohio, balked. Hadn’t George Washington, Taft noted, declared it was “our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances?” Had not Jefferson called for “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none?” Well, Harry Truman—the accidental president and product of corrupt Kansas City machine politics—had decided otherwise, and a compliant Congress and populace would follow him blindly.

Sen. Taft—known as “Mr. Republican”—knew he would be on the losing end of the vote but made sure to say his piece and raise questions about the nature of the NATO alliance that continue to resonate to this day. “By executing a treaty of this kind,” he told his colleagues, “we put ourselves at the mercy of the foreign policies of eleven other nations.” True. Those 11 nations billed NATO as a defensive alliance, but, asked Taft, would the Russians see it that way? Hardly. Taft then took the concept of the alliance to its (slippery) logical conclusion. “If the Russian threat justifies arms for all of Western Europe,” he declared, “surely it justifies similar arms for Nationalist China, for Indochina, for India, and ultimately for Japan; and in the Near East for Iran, for Syria, and for Iraq. … There is no limit to the burden.” Right again.

Taft received a standing ovation for his soaring, sensible rhetoric but won only 13 votes from his colleagues. His assertions would ultimately be proved right on many levels. NATO marked the end of the dream—manifested in the United Nations—of internationalism and signaled a return to power politics. Taft saw that a hardening of either side in the Cold War would severely limit the potential of the infant U.N. The NATO alliance, he thundered, was a violation of “the whole spirit of the United Nations charter … it necessarily divides the world into two armed camps.” Indeed it did. And the division remains. Because of NATO—to which the U.S. is still obligated by treaty—America could be drawn into a war, perhaps a nuclear war, over Lithuania, a country few U.S. citizens could locate on a map. That is Truman’s legacy.

It didn’t have to be this way. There were prominent dissenting voices at the time, though they were quickly “redbaited,” silenced and ushered to the political margins. One such figure was FDR’s former vice president, Henry Wallace. Wallace, then serving as Truman’s commerce secretary, wrote a long letter to the new president in 1946:

How do American actions since V-J Day appear to other nations? I mean by actions concrete things like $13 billion for the War and Navy Departments … tests of the atomic bomb and continued production of bombs … and the effort to secure bases spread over the globe from which the other half of the globe can be bombed. I cannot but feel that these actions must make it look to the rest of the world as if we were paying only lip service to peace. …

Then Wallace took it a step further. The U.S. should offer “reasonable … guarantees of security” to the Soviets “and allay any reasonable Russian grounds for fear, suspicion, and distrust.” We “must recognize … there can be no ‘One World’ unless the U.S. and Russia can find some way of living together.” Truman and probably most (by then) brainwashed Americans were in no mood for such idealism, which was fantasy as the president saw it. He mostly ignored the former vice president, and, when Wallace took his views public at Madison Square Garden, Truman demanded his resignation from the Cabinet. From then on, the Democratic Party establishment worked tirelessly to paint Wallace, who himself was a Democrat, as a “pinko” and a “commie” and banished him from the limelight.

And so the war drums beat on, catapulting the U.S. (and the never-so-innocent Soviet Union) from one crisis to another. In June 1948, Russians blockaded U.S.-occupied West Berlin. In the standard American version of events, the Soviets did so as an act of outright aggression, a test of Truman’s manhood and fortitude even. The story at the center of the American public’s attention was the subsequent “Berlin Airlift” of supplies into the city by aircraft of the U.S. military, an effort that went on round the clock until Stalin backed down. What is forgotten is the cause of the Soviet blockade. Mainly Stalin was frightened by Western plans underway (against earlier agreements) to unite the three occupation sectors (French, British, American) of Germany into a strong, coherent, independent West German state. The Russians, from this perspective, had genuine cause to fear a reunited German entity, especially since Germany’s west held most of the country’s industrial capacity. But Stalin backed down in the face of stunning American airlift capacity (something the Soviets could then never have pulled off), and—just as he had feared—West Germany did become an independent republic, rearmed and soon joined the anti-Soviet NATO military alliance.

Then, in order to bolster Western Europe’s purchasing power and stabilize local economies, Secretary of State George Marshall announced his plan—the Marshall Plan—to provide substantial financial aid to the European continent. This was, in fact, a remarkably generous and successful program; one need only look to the relative prosperity of Europe today for proof. The aid was even offered to the Russians and their Eastern European clients, but, with so many strings attached, the Soviets (perhaps unwisely) turned it down. Stalin correctly smelled a capitalist rat. The Marshall Plan did have ulterior motives, mainly to discredit and undermine the collectivist narratives of Western Europe’s then powerful communist political parties and to establish a capitalist monopoly on the continent west of Berlin. These motives were unmistakable even back in 1947, when future Secretary of State Dean Acheson proclaimed to fellow Americans in a State Department publication, “These measures … have only been in part suggested by humanitarianism. … Your government … is carrying out a policy of relief and reconstruction chiefly as a matter of national self-interest.” National interest over internationalist solutions—it was to be the story of the Cold War.

Next, in 1949, China fell to its local communist insurgency. This was a disaster for men like Wallace who had dared imagine an “other” world, “One World.” Having already foolishly divided the globe between two ideological camps, Truman—and his critics on the right, who were even more hawkish than he was—could not see this turn of events as anything other than a “win” for the Soviets and a supposed (but not actual) monolithic global communism. It mattered not that Stalin had offered scant support to Mao’s communists, that Russia and China were historically natural enemies (they had spilled blood on their borders by the 1960s) or that Mao’s foe, the Nationalist opposition headed by Chiang Kai-shek, was corrupt, brutal and somewhat dictatorial in its own right. Those were seen as mere details, “egghead” intellectual hogwash. The most populous nation on the planet had “turned Red,” and that called for anti-communist “toughness” at home and abroad. In a sense, the Republicans and conservative Democrats would never forgive Truman for “losing China”—as if it ever was ours to lose—a sentiment that inflicted a psychological wound far deeper than any actual strategic wound on the capitalist West.

So it was, as the middle of the 20th century arrived, that Truman and the U.S. became trapped in a bind of American making. After the fall of China, it was clear that the president—having described the world in binary, Manichean terms—had laid an enormous (perhaps impossible) task before the nation: to check and balance now Eurasian-wide communism and prevent its further spread by any means necessary. This expensive, dangerous and ultimately hopeless policy combination of “containment” and “rollback” would characterize the next 40 years of U.S. foreign relations. A bloody war in Korea was the first—though far from last—result of Truman’s bifurcated world vision. We will consider the Korean War in more detail below, but no doubt the horror of that unexpected military clash both influenced Truman’s decision not to run for re-election and helped bring about the triumph of national hero Dwight Eisenhower as a Republican in the 1952 presidential election.

Ike, as Gen. Eisenhower was known, was actually skeptical of big government spending and aggressive international interventionism. After all, he had served his nation in another time, an era of more limited foreign engagement. Still, as a Republican and product of his moment, Ike was constricted in his choices and vision. So it was that, in 1953, when Stalin died and his seemingly more amenable heirs came to power, the U.S. president would squander an opportunity to defuse tensions and substantially reduce defense expenditures and the growing arms race. When the Kremlin leadership called for a new summit meeting, Ike ignored the advice of his old comrade, Britain’s usually uber-hawkish Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and declined. He was a newly inaugurated president, after all, who had run his election campaign on the premise that Truman and other Democratic leaders were soft on communism. As a Republican dependent on conservatives in Congress, he could not politically risk another “Yalta conference” that carried the stigma of compromising with the “enemy.” It was the ultimate lost opportunity.

Eisenhower did, however, devise a unique way to lower defense expenditures and balance the budget (a pet project of his) during his two terms as president. He decrease America’s reliance on conventional ground forces and expanded the nation’s nuclear arsenal and capabilities. Letting the Soviets know about this new strategy was key. Rather than duke it out with communists in the mud of Korea or some other meaningless locale, the United States would declare a right to “massively retaliate” against any perceived Soviet aggression with nuclear weapons. This was genuinely scary talk. Though such a policy might have made some sense in 1946—when the U.S. held a nuclear monopoly—it seemed suicidal in the 1950s, a time when the Soviets, too, possessed nuclear arms. It raised serious logical questions: Would the U.S. sacrifice London or New York to save Seoul or Berlin or some other border-nation metropolis? We’ll never know the answer.

The reliance of Eisenhower’s strategy on nuclear retaliation often created political momentum for the use of such weapons. On a number of occasions—such as when the French garrison was besieged by communist insurgents in Vietnam, and when Mao’s Red Chinese shelled the small Nationalist-held coastal island of Quemoy—serious policymakers in the administration advised Ike to use “nukes.” And, in the Chinese islands crisis, when the chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff publicly asked “what America’s nuclear weapons were for, if not for use in such crises,” the rightfully freaked-out British sought assurance from Eisenhower that nuclear war wasn’t actually on the table.

“Massive retaliation,” as it was dubbed, actually represented a scary escalation of apocalyptic rhetoric. Still, there is doubt that Eisenhower the man ever seriously considered using the bombs. The former general hated war, had been horrified by the sight of battlefields in Europe and may have been bluffing in order to avoid future Korea-style regional wars. Ike’s defenders, then and now, argued just that. Certainty on this question, of course, is unattainable, but we do know that throughout the Eisenhower administration no more than a handful of U.S. soldiers died in combat the president had initiated. How many U.S. presidents—before, but especially since—could boast such an accomplishment?

This is not to imply that Ike’s hands were clean or that he didn’t contribute to the militarization of the amped-up Cold War. Indeed, just as Sen. Taft had predicted, the NATO alliance would expand and further be militarized during Ike’s tenure. When war broke out in Korea under Truman in 1950, ironically, rather than focus more on Asia, the Western European powers became convinced that this local war was just a distraction for an impending Soviet invasion of Germany and France. No such plan, or at least intention, existed, of course. Nonetheless, throughout the 1950s, the NATO allies demanded (and received) ever more U.S. Army infantry and armored divisions in Europe. In an even more controversial move, NATO even decided to form an independent Federal Republic of (West) Germany, arm it with $4 billion in American loans and welcome it into the alliance!

Only a decade had passed since Nazi Germany unilaterally conquered the mainland of Europe, and Russia was understandably horrified when the country of West Germany suddenly appeared in 1949. NATO, going a step further, even formed its own integrated army! Once again, Sen. Taft read the expansion of NATO as an unnecessary propellant for Cold War tensions. The creation of an armed German rump state and a NATO army, Taft declared, was a mistake, and he concluded:

I believe that the formation of such an army, and its location in Germany along the Iron Curtain line … is bound to have an aggressive aspect to the Russians. We would be going a long way from home, and very close to the Russian border. … The formation of this army is more an incitement to Russia to go to war rather than a deterrent.

Taft, in still another defeat, was right again. Nine days after the formal acceptance of West Germany into NATO, the jittery Soviets guided the hands of East German leaders and other East European states to sign a counterbalancing Warsaw Pact alliance. It was the West, not the Soviets, that started the world on the road to dichotomous military alliances.

If Eisenhower detested conventional wars and the deaths of American soldiers, he showed no such concern for the sovereignty, liberty or lives of foreigners. The president remained determined to combat communist “aggression” wherever it should rear its ugly head, and his tool of choice was not the U.S. military but the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Operating in the shadows, under Ike’s orders, the CIA funded rebels, masterminded coups, coordinated airstrikes and took any other actions necessary to topple left-leaning figures—often democratically elected—across the globe. “Successful” (in the short term) though most of these operations were, the U.S. still lives with the consequences, the “blowback,” from such international illegal operations.

When populist, elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh of Iran threatened to nationalize his country’s foreign-exploited oil resources in 1953, the CIA and British intelligence (MI6) helped to overthrow him. A dictatorship ensued under the Western-friendly but brutal Shah of Iran. The U.S., a nation formed in opposition to monarchy, had installed a king in a distant land.

Soon afterward in Guatemala, the elected, reformist, somewhat leftist President Jacobo Arbenz nationalized 250,000 acres owned by the U.S. corporation the United Fruit Co. In reaction, the CIA trained and supplied a small army of insurgents to topple him. When the U.S.-sponsored ground attack stalled, planes piloted by Americans bombed the capital, Guatemala City. Arbenz fled and a murderous (but pro-American) general, Carlos Armas, took over.

The American track record of foreign meddling only worsened as the 1950s wore on. When Ike ordered Gen. James Doolittle of World War II fame to review the activities and goals of the CIA, the resulting report summarized the spy-infused spook-thinking of the Eisenhower-era Cold War. Doolittle concluded, “It is now clear that we are facing an implacable enemy whose avowed objective is world domination. … There are no rules in such a game. Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply” (emphasis added). As if to prove Doolittle correct, U.S. propaganda broadcasts encouraged Hungarian rebels in 1956 to fight the Soviets. The rebels died by the thousands in the streets of Budapest when the expected American aid never arrived.

Under Ike, U.S. cash bought votes in Syria; U.S. advisers illegally intervened to elect a Philippine president; U.S. operatives gave financial and logistical support for an uprising that toppled the government of Indonesia (Suharto, the successor president, would later be responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths); and, in a demonstration of vicious absurdity, the CIA planned to assassinate the popular Congolese President Patrice Lumumba. His own domestic enemies got to Lumumba first, but not for lack of CIA effort. The agency’s director, Allen Dulles, had cabled the CIA’s local station chief, “We conclude that his [Lumumba’s] removal must be an urgent and prime objective.” This was as good as a death sentence for the Congolese populist. Had he not been killed by his domestic opponents, he may well have met an even more gruesome death—the CIA’s biological warfare bureau was in the process of selecting a pathogen to knock Lumumba “out of action.”

By the middle of Eisenhower’s two terms in office, most countries had been pressured to line up on one side of the geopolitical and ideological fence or the other. And the dirty truth was the United States found itself backing nearly as many crackpot despots as the Soviet Union. This included American backing for such royalists as the Shah of Iran and the king in Saudi Arabia, elected autocrats in South Korea and Taiwan, and military coup artists who ruled in Thailand, Pakistan and much of South America. This, to be sure, was not the postwar world that FDR and Churchill had, ostensibly, dreamed of aboard their ships in the North Atlantic as they signed the Atlantic Charter. Still, 15-odd years later this was the world as it was, and in many ways remains.

Korea: The First ‘Forgotten War’

“Korea came along and saved us.” —Secretary of State Dean Acheson, referring to his successful effort to convince Congress to adopt his recommendation of an increased military budget

Here’s a contentious assertion: The military conflict in Korea was an absolute bloodbath and an unnecessary waste that never would have continued as long as it did if television technology had been available then to project the ghoulish images of war into American homes every day. To say this is not to deny that today, as it turned out, South Korea is a far more vibrant, open and preferable environment than contemporary North Korea, dominated by an unhinged dictatorial regime. Rather, it is a statement that some 65 years ago such a war could have been avoided and, if not, certainly limited in scope and duration. That it was not is an indictment of leadership decisions made at the time, in Moscow, Beijing and Pyongyang, to be sure, but also in Washington, D.C.

At the end of World War II, just after the Russians had intervened in the Eastern theater at the eleventh hour in Manchuria, a tacit agreement was reached for Soviet troops to occupy the northern half of the Korean Peninsula (above the 38th Parallel), while U.S. troops occupied and administered the southern half. As Cold War tensions rose, each party backed a communist or capitalist regime in its own sector. Still, by 1950, it was unclear that the division of Korea would be permanent. In fact, U.S. and Soviet troops had already left the peninsula, and—in an unwise public statement of defense strategy—Secretary of State Acheson left South Korea off his list of countries within his defined American “defense perimeter” in Asia. This may have been an oversight, but the gaffe undoubtedly encouraged the North Korean communists to consider an invasion of the south.

When the North Korean army rolled across the border in late June 1950, a de facto state of war—often forgotten now—already existed on the peninsula. Partisan attacks from both sides of the parallel cost some 100,000 Korean lives between 1945 and 1950. At the time of the invasion, however, U.S. officials were convinced that global communism was a monolith and that Stalin was directly behind the action. Once again, American leaders misread Stalin’s role. President Kim Il Sung of North Korea masterminded the invasion himself, fearing—with some cause—that Syngman Rhee’s autocratic southern statelet might soon invade the north and hoping a North Korean invasion would spark a national communist revolution. It didn’t. Stalin, in fact, had initially resisted Kim’s plans to attack, assented only at the last moment, and never provided the level of Soviet arms and air support that Kim thought had been promised to him. Still, in President Truman’s binary world, the North Korean attack was read as a direct provocation from Stalin. If the U.S. didn’t stand tall in Korea, Truman feared, his domestic political opponents would brand his administration with the odious terms “Munich” and “appeasement.”

So, though Kim’s supposed revolution never erupted, North Korea’s Soviet-supplied tanks did initially roll over the surprised South Korean defenders. The capital of Seoul soon fell, and total conquest of the peninsula seemed likely. At this point Truman made two monumental decisions: (1) to commit U.S. ground forces to fight on the Asian mainland, to engage in combat not five years after the Second World War had ended, and (2) not to seek congressional approval or a declaration of war. Decision No. 1 sentenced tens of thousands of GIs to die in Korea’s rugged terrain; the second decision set a dangerous (unconstitutional) precedent, that executive war powers were so broad that Congress had almost no role to play in war-making outside an advisory and financial capacity. Read backward from the present, with U.S. troops engaged in several undeclared wars, it is the second decision that looms larger and turned out to be more fundamental.

Truman, at first, wouldn’t even call it a war; rather he termed it a “police action” in front of reporters. Four days into the invasion, with American air and naval support already engaged, and GIs 24 hours away from spilling ample blood in Korea, Truman foolishly announced in a press conference, “We are not at war.” Still, despite his horrifying precedent and early mismanagement of the war, the American people—patriotic as ever—initially rallied to the president’s cause. Congress, too, was acquiescent. When Truman announced his unilateral deployment of troops to combat he received a standing ovation in the legislature. Congress then authorized him to call up the reserves and extended the draft.

For all that, the U.S. Army did not perform well early in the war. Douglas MacArthur, America’s celebrity general, had poorly trained and prepared his occupation soldiers stationed in Japan. The units were poorly equipped, ignorant of Korea’s terrain and—typically—their commander (known as Mac) had utterly underestimated his adversary. In the first two weeks, U.S. and its allied forces suffered 30 percent casualties and were pushed into the small “Pusan Perimeter” on the far southeast of the peninsula. Eventually, as reinforcements poured in, MacArthur pulled off a military masterstroke, a risky, enveloping, amphibious invasion behind the North Korean lines at the port of Inchon. Almost at once North Korean resistance collapsed, and the invaders fled northward in disarray. This was Mac’s last miracle, however. In reality the “general in chief” was a walking problem.

Known to be arrogant, self-important and often foolhardy, MacArthur wasn’t popular even among those who had been his fellow senior officers in the late world war. Omar Bradley thought him vain and domineering. Eisenhower felt the same way; once asked whether he knew MacArthur, Ike had said, “Not only have I met him … I studied dramatics under him for five years in Washington and four in the Philippines.” President Truman, too, thought little of the ambitious general. Truman referred to him in his journal as “Mr. Prima Donna, Brass Hat.” However, after Inchon, MacArthur’s optimistic theatrics would encourage Truman to make his worst, and most fateful, decision of the war: to go beyond the original United Nations mandate and attempt to unify the entirety of Korea under the capitalist Rhee regime. From the Soviet perspective, and especially that of the nearby Chinese, this escalation understandably read as Western aggression. Still, at the time, for Truman it seemed a non-decision. Public opinion clamored for it, MacArthur demanded such a strategy and the Pentagon dare not defy the president. It was a recipe for disaster.

The Chinese, meanwhile, had given ample warning they might intervene, especially if U.S. troops approached their border along the Yalu River. From their, rather rational, perspective, U.S. intervention in the distant Korean War was little more than a pretext for renewed intervention in China in the wake of the recently concluded civil war there. One can see why the Chinese thought this way. Truman had ordered the U.S. fleet into the narrow strait dividing mainland China from the final Nationalist stronghold (and rump state) on the island of Taiwan. What’s more, recently the U.S. had refused—in its capacity as a permanent U.N. Security Council member—to seat Mao’s Chinese delegation, instead maintaining the official charade that Chiang’s tiny island redoubt was the real China. This fiction would endure for a few more decades. Finally, as U.S. troops—under MacArthur’s own foolish orders—did approach the Yalu River, the Chinese were not unaware of American boasting about military successes in Korea and the calls from congressional conservatives to “smash the Chinese revolution.” In this setting, the Chinese, it appears, genuinely feared for their safety.

So it was that even with MacArthur predicting the troops would be home by Christmas, and having told Truman there was “very little” possibility of Chinese intervention, hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops poured across the Yalu River. In bitterly cold weather, Mao’s battle-hardened veterans of the Chinese civil war drove through and around the surprised and flat-footed Americans. Though extraordinary heroism would save most American units from destruction, MacArthur’s earlier carelessness and exuberance had contributed to their tactical woes—he had left massive gaps between the two main Western armies on the peninsula. The average GI, not MacArthur in his gold-brimmed hat, would suffer the consequences. In a humiliating retreat, the Americans lost Seoul before stabilizing the lines. It was the second time enemy forces had taken the city.

Mortified by the setback, MacArthur lashed out and demanded—publicly—the crazy, the impossible: atomic bombing of Chinese industrial targets (read: cities), the unleashing of Chiang’s army into the fight and a complete blockade of the massive Chinese coastline. Truman fumed over this frantic insubordination but kept cool publicly. After all, the Democratic president had domestic political opponents to deal with—and they, mostly Republicans, were encouraging him to follow Mac’s advice and extend the war into China.

After Christmas, a new tactical commander under MacArthur, Gen. Matthew Ridgway, led a successful limited counterattack that regained Seoul and established fixed frontlines generally along the 38th Parallel. There the lines of a stalemated war would basically remain for the next two years. Then MacArthur, finally, perhaps inescapably, committed career suicide once and for all. He, a serving U.S. general in the field, sent a critical anti-Truman letter to the opposition Republican leader in the House of Representatives, Joseph Martin. An elated Martin read the letter on the floor, including one bit where MacArthur declared that the “[Truman] administration should be indicted for the murder of American boys.” This display of staggering insubordination was the last straw for Truman, who, with the assent of the Joint Chiefs, summarily fired Douglas MacArthur, the American hero.

Truman’s decision was the right, really the only, one for an American president. MacArthur had not only tested the very limits of civilian control of the U.S. military, he had also been dead wrong in his increasing unhinged counsel and demands. His preferred course of accepting “no substitute for ‘victory’ ” (a concept still taught at West Point!) would have utterly trashed relations with terrified NATO allies, killed untold millions in a prolonged ground war with China, murdered countless Asian civilians under American atomic bombs and, potentially, set off a cataclysmic global nuclear war with the Soviet Union. All that aside, MacArthur, it seems, got the last word.

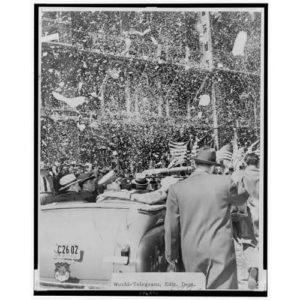

Mac was welcomed back to the United States (his first time home from Asia in 13 years) as a conquering hero. It’s no wonder MacArthur’s most famous biographer titled his book “American Caesar.” Within weeks the general addressed a joint session of Congress and was interrupted by applause 30 times in a 34-minute speech. After the booming oratory, MacArthur rode triumphantly down Pennsylvania Avenue, with bombers and fighters flying in formation overhead, as a crowd of 300,000 cheered him on. The next day, New York City threw him a ticker-tape parade. Some estimates placed the crowd at 7.5 million. A Gallup survey indicated that 69 percent of the American people sided with him over Truman. Within 12 days, Truman received more than 20,000 letters about the general, and they ran 20 to one in favor of MacArthur. Some letters were so overtly hostile and threatening that they were shown to the Secret Service.

Given all this madness, it’s difficult to know who really won the epic battle between MacArthur and Truman. One surmises that MacArthur won the popularity contest, but Truman and the senior generals got their way when it came to policy. Finally standing up to the now-dismissed MacArthur, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Omar Bradley announced that he had always supported the president and believed that MacArthur’s recommendations “would involve us in the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.”

What we can say is that the war that already existed continued, just as before; only now it played out as a grueling stalemate. The grand theatrics over, war dragged on and on. Though there was no organized antiwar movement to speak of in the pre-Vietnam era of 1950s patriotism, the war became wildly unpopular with the American people. Dubbed “Truman’s War,” and with thousands of GIs—45 percent of U.S. casualties occurred in the stalemated final 28 months of war—dying on meaningless pieces of high ground like “Heartbreak Ridge” and “Pork Chop Hill,” the populace began to wonder what it was all for.

Still, peace talks that began in July 1951 had their own stalemate, eventually two years long, before the exhausted Chinese and North Koreans came to terms. During the stalemate, the frustrated American public, desperate to end the war—but not willing to simply quit the fight—began again to consider MacArthur-like solutions. According to one November 1951 poll, 51 percent of Americans favored using the Bomb on “military targets” (whatever that meant in practice). When peace came, in July 1953, it was far from clear exactly what had changed. Some writers point to Stalin’s death and surmise that the new Soviet leaders pressured the Chinese and North Koreans to back down and accept the terms. Hawkish historians often imply that newly elected Ike had secretly threatened to use nuclear weapons upon his ascension to office. This is unproved. Most likely, the Chinese and the Koreans of the north were exhausted, just as the Americans and the Koreans of the south were by mid-1953. In the end, perhaps, it took a Republican president and former general like Eisenhower to bring the war to a conclusion. Eisenhower accepted terms for the cease-fire without gaining any major concessions from the enemy. Had Truman accepted such an armistice, he would have been attacked from the right, but Ike was a newly elected Republican and his party now controlled the legislative branch as well. As the historian H.W. Brands wrote, “If anyone could end the awful stalemate, it was Ike.” That may ultimately have been the case.

Contrary to many later assertions that U.S. entry into the Korean War was humanitarian in nature, it must never be forgotten that America waged a vicious campaign. U.S. planes dropped 635,000 tons of bombs on the small peninsula, more than the combined total dropped in the Pacific theater of World War II. The bombing only contributed to a land-based “scorched earth” policy in which U.S., South Korean and other allied troops wiped thousands of villages off the map and destroyed irrigation systems that fed the land. Thousands of Koreans starved to death. These were but a tiny fraction of the 2 million Korean civilians who perished under the bombardment and seesaw land invasions—some 10 percent of the prewar population of the entire peninsula.

The war in Korea ended as a draw, with the frontline running along the 38th Parallel line. The peninsula wasn’t to be unified (it still isn’t) either by communists or capitalists. Neither the Americans, Soviets or Chinese appear to have had it in their power to achieve this. And so, for the accomplishment of basically nothing, the U.S. suffered 33,000 combat deaths and the Koreans took 4 million casualties (killed, wounded, missing), most of them civilians. For all that, the supposedly invincible United States did avoid the communist takeover of the south. Still, by shifting early in the war’s first year to an offensive strategy to reunify the entire country for capitalism, it provoked Chinese intervention, and, once the war settled into a stalemate, the U.S. could not agree to an acceptable armistice for more than two bloody years. That (mostly) Korean blood must rest, at least partially on America’s hands.

Commies on Every Corner: The Postwar ‘Red Scares’

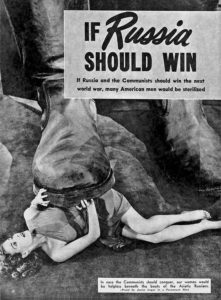

Foreign enemies, real or imagined, are by nature the friend of centralized government and the foe of civil liberty. America’s hyper-opposition to communism in the 1940s and ’50s demonstrates this truth as clearly as any other national scare in U.S. history. Some of the fear was genuine, a grass-roots civilian response to a scary nuclear-armed world; still, it must be said that much of the panic was artificial, sown externally by senior government elites with political and economic motives to pursue through an external “Red Scare.” Much was lost—social goals not sought, art not crafted and individual liberties not protected—amid anti-communist hysteria. As we will soon see, one is tempted to conclude that the Cold War, such as it was, existed most fervently in the head of America and Americans; more real, there, in fact, than along the divided frontier of East and West Berlin. War, as the progressive intellectual Randolph Bourne once wrote, “is the health of the state.” But wars—the finite type that governments declare and wage—end. Cold wars, on the other hand, can conceivably last forever, to the glee and forever health of the state and its arms manufacturing oligarchs. This was, and is, the power of perpetual militarism at home and militarized standoffs abroad. The 1940s and ’50s, then, manifested as an Orwellian world—one, indeed, which Americans still inhabit today. Global communism is gone, but global “terror” quickly replaced it; Stalinist Soviet “aggression” is dead, but the Russian bear in the form of Vladimir Putin is alive and well. Let us think on that in analyzing the Red Scare of the early Cold War.

The wave of fear that gripped the nation during the early Cold War showed itself politically as well as socially. It affected a variety of American institutions, from Hollywood to the legislature to the living room. In the political realm, conservative Democrats and newly resurgent Republicans manipulated anti-communist sentiment to attack even modestly liberal opponents, thereby temporarily closing the book on FDR-style social welfare. Everyone, it seemed, played the redbaiting game, but few did it better than rising Republican star Richard M. Nixon. Running for a U.S. Senate seat in California, Nixon labeled his opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas, “Pink right down to her underwear.” He called her the “Pink Lady”; she dubbed him “Tricky Dick,” a nickname that stuck. Covering the campaign, a columnist at The Nation remarked upon Nixon’s “astonishing capacity for petty malice.” Right the author was, of course, but Nixon won the Senate seat and went on to be one of the most hawkish Cold Warriors in Washington before serving as Eisenhower’s vice president (1953-61).

If Nixon was just beginning his career-long campaign of malice, the real heavyweight of hysterical anti-communism on Capitol Hill was Wisconsin’s Republican Sen. Joseph McCarthy. His was the most virulent, damaging and ultimately absurd brand of redbaiting. The wildly delusional McCarthy seemed to see commies on every corner. He rose to prominence when he delivered a now-famous speech to a Republican women’s club in Wheeling, W.Va., in which he thundered, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 names that were made known to the Secretary of State as members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department.” He had, of course, no list. Time and again over the years, doubters demanded to see this list or other such documents that the senator allegedly held, but McCarthy regularly brushed them off and never produced one. What’s more, the number of “known communists” on McCarthy’s list changed, from 205 to 57 to 81, over just a few months.

Boisterous public theatrics masking personal fraud was the name of the game for McCarthy. Running for office in 1946, his campaign relied on his supposed World War II record as a combat flyer in the Marine Corps, dubbing him “Tail Gunner Joe.” Joe was little more than a blatant liar. He claimed to have flown 30 combat missions; in fact, he had gone on none. Later, he would walk around Washington with a limp that he said was caused by “ten pounds of shrapnel” that earned him a Purple Heart. Actually he had hurt his foot in a fall down a set of stairs at a party. In addition to being a pathological liar, the senator was a drunk, a braggart and a bully. He carried bottles of whiskey in a dirty briefcase that he claimed was full of his famous “documents,” and bragged that he could put away a fifth of whiskey a day. Most of all, McCarthy loved hypermasculine bravado. He referred to some supposed subversives as “homos” or “pretty boys”; those who opposed him were “left-wing bleeding hearts” or “egg-sucking phony liberals”; he leered at and otherwise sexually harassed attractive women who appeared before his many committee hearings.

McCarthy was a loose cannon and rarely, if ever, backed up his hyperbolic claims. He almost never followed up on his charges, and he never identified a single subversive by name. Eventually, Democrats and some sober Republicans tried to investigate and refute the man. A committee led by Democratic Sen. Millard Tydings exposed a litany of lies and exaggeration surrounding McCarthy. The majority report concluded that, taken as a whole, McCarthy’s claims were “a fraud and a hoax perpetrated on the Senate of the United States and the American People.” Still, McCarthy survived the hearings and continued on his crusade. He wasn’t down yet. Indeed, between 1951 and 1954 he led no fewer than 85 committee investigations into domestic communist influence.

Eventually, however, as much of his deceit came to light, McCarthy went too far. In what became known as the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954, the senator questioned Gen. Ralph Zwicker—holder of a Purple Heart and a Silver Star medal—and told the man he had “the brains of a five-year-old child” and was “a disgrace to the army.” After that incident, McCarthy was eviscerated on television by the legendary CBS anchor Edward R. Murrow. Then, later in the hearings the Army’s chief counsel, Joseph Welch, interrupted McCarthy to famously ask, “At long last, do you have no decency, sir?” Welch received a standing ovation. McCarthy was bewildered; he didn’t realize his public career essentially had ended. After that, President Eisenhower—who, even though he found it politically expedient to stay silent on McCarthy’s antics, had never cared for the man—removed McCarthy from the list of welcome guests at the White House. “It’s no longer McCarthyism,” Eisenhower declared, “It’s McCarthy-wasm.” That December, the Senate voted 65-22 to censure McCarthy. (Sen. John F. Kennedy, whose brother Bobby worked as an aide to McCarthy, and whose father staunchly supported the Wisconsin Republican, was the only Democrat not to publicly support the censure. In fact, when still a member of the House, the future president once claimed that “McCarthy may have something.”)

Three years later, the chronic alcoholic died at age 48. Yet his legacy and spirit lived on. Students of the era should never forget how popular McCarthy was among significant segments of the American people, or how small was the number of Republicans—and even Democrats—who would defy him in the early days. If McCarthy lost the practical battle to prove a vast conspiracy—which never really seemed to be his true motive or priority—he succeeded in pulling American politics and culture to the right and popularizing an anti-communist frenzy (and tactics) that outlived the man himself. The era of McCarthy, even today, is far from dead.

The fact that McCarthyism eventually fizzled out and in the end the man was disgraced does nothing to minimize the damage caused to the senator’s victims. Though the State Department didn’t find any truth in McCarthy’s initial allegations of communist infiltration, at least 90 employees of the U.S. foreign service were fired as “security threats.” This was in an era when to be gay was equated with anti-Americanism and vulnerability to blackmail. Indeed, the hunt for government-employed gays became a national priority in some powerful minds. Roy Black, then the head of the District of Columbia vice squad, called for a national task force because, he claimed, “There is a need in this country for a central bureau for records of homosexuals and perverts of all types.”

Congressional legislation also reflected the worst instincts of McCarthyism during this and earlier periods. Truman’s 1947 Executive Order 9835 set up “loyalty boards” in all federal government agencies (which employed some 2.5 million people). The loyalty boards played it fast and loose with regard to civil liberties protections, denying accused government workers the right to know the identity of their accusers—often undercover FBI agents—or to confront them in court hearings. Indeed, many of those employees investigated were guilty of little more than belonging to vaguely liberal organizations. In 1948, Truman’s administration went further, actually prosecuting the senior leadership of the American Communist Party on trumped-up charges.

The national legislature also got in on the game. In 1950, Congress passed the Internal Security Act—over Truman’s courageous veto, it must be said—which required all American communists to “register” with the attorney general. A year later, the Supreme Court in a 6-2 ruling upheld the Smith Act, which held that the First Amendment protections of free speech, press and assembly did not apply to communist citizens. One of the two voices of reason on the court, Hugo Black, delivered a pained dissent, writing, “There is hope, however, that in calmer times, when … passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.” It is important to keep in mind, also, that support for anti-communist political legislation was never limited to Republicans. Democrats and various establishment leftists, especially after the “loss” of China, jumped on the commie-bashing express—some out of genuine agreement, others out of a sense of self-preservation within the prevailing winds.

These dubious bills may have been a lot of things, but what they were not was a proportional response to the actual threat of communism in America. By 1950, membership in the U.S. Communist Party—never very high—was at its lowest level since the 1920s. Out of a population of 150 million, the U.S. counted only some 30,000 members. The party actually received little support from Moscow and had never been a very potent force in American politics. Ongoing pressure and prosecution of card-carrying Communist Party members were so intense that by 1957 membership plummeted to about 5,000 members. So many of them were FBI agents that bureau chief J. Edgar Hoover considered massing his men to take over the party at a key leadership conference. Also, for all the talk of spies, subversion and communist trickery in the U.S., not a single public official was convicted of spying at any time during the postwar Red Scare. (The case of Alger Hiss, a State Department official, dealt with perjury counts, and the husband and wife convicted of espionage and executed in the infamous Rosenberg case were not government officials.)

Just as in the 1920s Red Scare—in which the bureau was an important player—the FBI played a nefarious role in the anti-communist hysteria of the 1940s and ’50s. Using surveillance, wiretapping and undercover informants—some of them religious figures, such as Cardinal Francis Spellman—agents of Hoover destroyed many a public reputation behind scant evidence. Critics of the FBI included U.S. journalist and writer Bernard De Voto, who in 1949 publicly decried the FBI leader’s use of “gossip, rumor, slander, backbiting, malice and drunken invention, which, when it makes the headlines, shatters the reputations of innocent and harmless people.” Such criticism of the bureau was rare, however, especially since it was widely alleged that Hoover kept detailed “blackmail files” on almost every major figure in Washington. Perhaps that’s why Truman would complain only privately about the FBI. Shortly after becoming president in 1945, he wrote out this private thought by hand: “We want no Gestapo or Secret Police. FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex life scandals and plain blackmail. … This must stop.” It didn’t.

In addition to clearing vile (perhaps unlawful) bills, key congressional committees also went on the anti-communist hunt. The most famous was the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), populated by some of the most hawkish and—predictably—bigoted representatives on Capitol Hill. Mississippi Sen. John Rankin used HUAC as a platform to attack and stymie the nascent black civil rights movement, calling it “a part of the communistic program, laid down by Stalin approximately thirty years ago. Remember communism is Yiddish” (emphasis added). Starting in 1947, HUAC’s attention turned to probing alleged left-wing activity in Hollywood. Seeing the investigation as an anti-artistic “witch hunt,” some famous entertainers courageously fought back. Judy Garland cried, “Before every free conscience in America is subpoenaed, please speak up! Say your piece. Write your Congressman a letter!” Frank Sinatra boldly asked, “Once they get the movies throttled, how long will it be before we’re told what we can say and cannot say into a radio microphone. … Will they call you a Commie? … Are they going to scare us into silence?” However, a big part of Hollywood was sympathetic to the HUAC investigation, and “friendly witnesses” before the committee included Gary Cooper, Walt Disney and an actor who later would be spending much time in the nation’s capital—Ronald Reagan.

There were serious consequences for some uncooperative members of the movie industry. After 10 unfriendly witnesses, dubbed the “Hollywood 10” (including famed screenwriter Dalton Trumbo), refused to testify at committee hearings, they were held in contempt and made to serve prison sentences of between six months and a year. They and hundreds of others were blacklisted by the movie industry.

Among the Hollywood celebrity victims who were damaged severely by redbaiting was Charlie Chaplin. The American Legion led protests against the pacifist message of his 1947 film “Monsieur Verdoux,” and, a few years later, while the British-born Chaplin was out of the United States, the government suspended his re-entry permit until he agreed to “submit to rigorous examination of his political beliefs and moral behavior.” He refused and remained in exile until 1972, when he returned to received a special Oscar. He died in Switzerland in 1977.