American History for Truthdiggers: Just How Good Was the ‘Good War’?

Many in the U.S. put a sentimental gloss on World War II, turning a blind eye to its complexity, savagery and dubious legacies. Grim duty during World War II: A soldier in the Quartermaster Corps Graves Registration Service examines a skull in attempting to identify the remains.

Grim duty during World War II: A soldier in the Quartermaster Corps Graves Registration Service examines a skull in attempting to identify the remains.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 26th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 26 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22; Part 23; Part 24; Part 25.

* * *

“For the past 50 years, the Allied war has been sanitized and romanticized almost beyond recognition by the sentimental, the loony patriotic, the ignorant, and the bloodthirsty.” —Former U.S. Army Infantry Lt. Paul Fussell, famed author and poet, in his 1989 book “Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War”

The United States’ role in the Second World War has been so mythologized that it is now difficult to parse out truth from fantasy. There even exists a certain nostalgia for the war years, despite all the death and destruction wrought by global combat. Whereas the cataclysm of World War II serves as a cautionary tale in much of Europe and Asia, it is remembered as a singularly triumphant event here in the United States. In fact, the war often serves as but a sequel to America’s memorialized role in the 20th century: as back-to-back world war champ and twice savior of Europe. The organic simplicity of this version suits the inherently American vision of its own exceptionalism in global affairs.

However, there is a significant difference between a necessary war—which it probably was—and a good war. In fact, “good war” might be a contradiction in terms. The bitter truth is that the United States, much as all the combatant nations, waged an extraordinarily brutal, dirty war in Europe and especially the Pacific. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt cut nasty deals and allied with some nefarious actors to get the job done and defeat Germany and Japan. In the process, he, and those very allies, shattered the old world and made a new one. Whether that was ultimately a positive outcome remains to be seen. Nevertheless, only through separating the difficult realities of war from the comforting myths can we understand not only the burden of the past but the world we currently inhabit.

For the United States, a two-front war was by no means inevitable. Tough talk and crippling sanctions helped push Japan into a fight in the Pacific that probably could have been avoided. And, though Roosevelt had been waging an undeclared naval war with Germany in the North Atlantic, Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor hardly guaranteed that a still isolationist-prone American public would support war in Europe. This was awkward in light of Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s secret policy of “Germany First” as a target in any future war. Lucky for them, Germany’s megalomaniacal Adolf Hitler spared them the trouble. Within days of Japan’s surprise strike on Pearl Harbor, Germany and Italy foolishly declared war on the United States.

Hitler misread American intentions and its military potential. In the wake of Pearl Harbor he declared, “I don’t see much future for the Americans. It’s a decayed country. And they have their racial problem, and the problem of social inequalities. … American society is half Judaized, and the other half Negrefied. How can one expect a state like that to hold together—a country where everything is built on the dollar.” While Hitler’s analysis of American social problems may have been astute in some respects, he underestimated the very power of that American dollar. His foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, had a more clear-eyed assessment, warning the fuhrer, “We have just one year to cut off Russia from her American supplies. … If we don’t succeed and the munitions potential of the United States joins up with the manpower potential of the Russians … we shall be able to win [the war] only with difficulty.” Here, Ribbentrop, up to a point, essentially predicted the near future and exact course of the conflict between Germany and its foes.

America’s allies were overjoyed by the Pearl Harbor attack and the subsequent German declaration of war. Churchill, whose nation had declared war on Germany in 1939 and who had always pinned England’s hopes on American intervention, remembered thinking when he heard of the Japanese attack: “So we had won after all. … Hitler’s fate was sealed. Mussolini’s fate was sealed. As for the Japanese, they would be ground to powder. … There was no more doubt about the end.” That night, Churchill wrote later, he “slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.” China’s Chiang Kai-shek was described as being “so happy he sang an old opera aria and played ‘Ave Maria’ all day.” He too foresaw his country’s salvation. Still, there remained a war to actually fight.

Who (Really) Won World War II?

Ask the average American who won the Second World War and you can count on a ready answer: The U.S. military, of course! Certainly the U.S. contributed mightily, but the truth is far less simple. By the end, more than 60 million people would die in the war, only about 400,000 of them American. Those figures alone point to the magnitude of the roles of nations other than the U.S.

There were three fundamental determinants of Allied victory: time, men and materiel. A longer war favored the Allies because of their manpower and economic potential. Both Germany and Japan pinned their hopes on a short war. But it was British and, even more so, Russian men who provided that time for what Britain’s Lord Beaverbrook called “the immense possibilities of American industry.” In the second half of 1941 alone, Russia had suffered 3 million casualties, and it would eventually sacrifice some 30 million (military and civilian) lives in the epic struggle with Nazi Germany. Eight out of 10 Germans killed in the war fell on the Eastern Front.

This is not to downplay the role of American might in the war’s outcome. As for materiel, the U.S. capacity for mobilization was uncanny. The national income of the United States, even in the midst of the Great Depression, was nearly double the combined incomes of Germany, Italy and Japan. Still, make no mistake, Russian sacrifice and Russian manpower were the decisive factors in Allied victory. That, of course, is a discomfiting fact for most Americans, especially because World War II was so quickly followed by a “cold war” between the Soviet Union and the U.S. But this doesn’t make it any less true. Indeed, a broad-stroke conclusion would be that Russian (and to some extent British) men bought the necessary time for American materiel to overwhelm the mismatched Axis Powers. Such an (albeit accurate) analysis is far less rewarding for American myth makers.

The United States was actually rather fortunate. Thanks to timing—it entered the war late—and geography, the U.S. could choose to fight a war of equipment and machines rather than men. This route would cost the least in terms of American lives and also had the ancillary benefit of revitalizing the Depression-era economy and positioning the U.S. for future global leadership. All this was possible thanks to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and the resultant fact that the U.S. homeland, almost alone among combatant nations, was untouched by the war itself.

U.S. military planning reflected these fortunate realities. Prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall assumed that Russia would fall and therefore victory in Europe would require some 215 American infantry divisions. However, as the war evolved—and especially after Germany’s defeat in Russia at the pivotal Battle of Stalingrad—it became apparent that the Soviets would survive. In response, the U.S. military truncated its mobilization to just 90 divisions. This “arsenal of democracy” strategy guaranteed that American industry would combine with Russian bloodshed to win the war. Thus, even though the United States did raise the largest army in its own history, that force remained smaller than Germany’s and less than half the size of the Soviet military.

Thus, while the untouched American economy expanded throughout the war, the Russian people faced economic contraction and diminishing quality of life in their titanic ground struggle with the Nazis. Due to the brutal German invasion, Soviet food supplies were cut by two-thirds, millions slid into destitution and many starved to death. In the U.S., by contrast, personal wealth grew and the American economy proved capable of producing ample amounts of guns and butter. Despite the undoubted courage of U.S. service members in combat, the average American’s chance of dying in battle was only one in 100, one-tenth the rate of the American Civil War. Furthermore, as a proportion of the total, U.S. military casualties were lower than among any of the other major belligerents in World War II.

By way of comparison, fewer Americans were killed than Hungarians, Romanians or Koreans. Twice as many Yugoslavians died as Americans, 10 times as many Poles and 50 times as many Russians. This reality was not lost on Josef Stalin and the often frustrated Russians. Even at its height, only 10 percent of U.S. lend-lease aid went to the Soviets, and, one Russian complained during the war, “We’ve lost millions of people, and they [Americans] want us to crawl on our knees because they send us Spam.” Even Churchill recognized the Russian point of view in early 1943 when he declared that “in April, May and June, not a single American or British soldier will be killing a single German or Italian soldier while the Russians are chasing 185 divisions around.” When the British prime minister spoke those words only eight U.S. divisions were in the entire European theater. Given this disparity, one understands Stalin’s frustration and his demand for the Western Allies to open a second front in France. Indeed, this concern animated much of the tension in the troubled alliance throughout the war.

The Politics of Alliance: The United States, Britain and the Soviet Union

The Big Three powers—Britain, the Soviet Union and the U.S.—forged what was ultimately an alliance of convenience and necessity, rather than ideology. For all the lip service paid to the liberal principles of the Atlantic Charter, the reality is that a flawed American democracy had little choice but to partner with an unabashed maritime empire (Britain) and a vast communist land empire (the Soviet Union) to fight international fascism. Such an alliance would be messy from the start.

The dynamics of the alliance were ultimately based on the different goals and relative positions of each partner. The United States was distant from the battlefields and endowed with extraordinary economic potential. It sought supremacy in the Pacific, relative stability and balance in Europe, and global economic dominance in the postwar world. Britain hoped merely to survive and then to salvage its still substantial global empire. The British wanted to maintain clout in Europe and ensure that no one continental power—whether Germany or the Soviet Union—dominated the region. Britain’s diminishing manpower and economic output meant that it required help from its larger partners. Stalin engaged in an existential fight with the Nazis and initially feared his nation’s utter destruction. Thus the Soviet Union had little choice but to work with—and receive aid from—the Western capitalist powers. Nevertheless, the Soviets still adhered to a revolutionary ideology of communist expansion, and, fearing future invasion from the West, hoped to create a friendly buffer zone of protection in Eastern Europe. This directly collided with the wish of the Western democracies to establish capitalist republics in the same region. Clearly the Allied positions and desires were often contradictory and affected the strategies of each power.

The defining issue—and point of contention—in the alliance was the Soviet demand for Britain and America to swiftly open a second front in Western Europe in order to take German pressure off the Russian heartland. This demand ran into limits of time—it would take the U.S. military quite a while to fully mobilize—and British hesitancy. Churchill remembered well the slaughter of trench warfare in the Great War and the embarrassment of the British army’s recent defeat in France and evacuation from Dunkirk. The British thus preferred peripheral actions that secured their empire and played to its strengths, at sea and in the air. The Americans, however, were willing and eager to quickly strike the heart of Germany to end the war, but they faced the reality that British manpower would form the bulk of troop strength in Europe for at least one or two years as Washington raised its army. Thus, throughout the war, a pattern repeated whereby the Western Allies delayed launching a second front in France and the Soviets expressed increasing frustration and, ultimately, mistrust of their capitalist partners.

In early 1943, leaders of the Allied Powers met in Casablanca. (With the Soviet Union beset with fighting, Stalin declined to attend.) At that conference Churchill maintained the leverage required to win the day. He convinced Roosevelt to first invade North Africa and take pressure off the British army, then grappling with German Gen. Erwin Rommel in Egypt. Without a fully mobilized force, Roosevelt had limited means to reassure the Soviet Union that a true second front was forthcoming. So he did his best, announcing a doctrine that called for nothing less than the “unconditional surrender” of Germany and Japan. This strategic straitjacket would eventually have significant effect on the war’s outcome, but did little to ease Stalin’s legitimate concerns. Roosevelt may have had little choice at the Casablanca conference but to defer to Churchill’s peripheral Mediterranean strategy, but American strategists had an additional fear. If the Soviets truly turned the tide of battle in the east—which seemed probable by 1943—before the Western Allies invaded France, might the Russians not dominate all of the European continent?

U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson recognized this at an early point, criticizing Churchill and the British plan. In May 1943, Stimson declared, “The British are trying to arrange this matter so that the British and Americans hold the leg for Stalin to kill the deer and I think that will be a dangerous business for us at the end of the war. Stalin won’t have much of an opinion [of that policy] and we will not be able to share much of the postwar world with him.” Furthermore, U.S. generals—imbued with the unique “American way of war” replete with overwhelming, swift offensives—saw a massive invasion of France as the only logical way to win the war and save the continent. Besides, any victory that kept American casualties relatively low required Russian survival. As Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, senior U.S. commander in Europe, emphasized in pushing for a rapid invasion of France, “We should not forget that the prize we seek is to keep 8,000,000 Russians in the war.”

As the British and Americans scuffled over the timing for an invasion of France, the date for a true second front was continually delayed. In May 1943, Roosevelt was still assuring Stalin that he “expected the formation of a second front this year,” and even added that in order to facilitate this, American lend-lease supplies to the Soviet Union would be cut by 60 percent. Of course, the reality was that no second front in France was forthcoming until at least spring 1944 so long as the British kept insisting on campaigns in Africa and the Mediterranean and in the air. British hesitancy and intransigence frustrated the American military chiefs to no end, and they recommended to Roosevelt in July 1943 that if the Brits didn’t relent “we should turn to the Pacific and strike decisively against Japan; in other words, assume a defensive attitude against Germany.” Such a move, in fact, might have been popular with an American populace that was, after the “sneak attack” on Pearl Harbor, more angry with Japan than with Germany.

Nonetheless, Roosevelt refused to back away from the “Germany First” strategy and overrode his military chiefs. Politics played a role here, as they often did for FDR. American mobilization took time, and the president felt he needed to unleash some sort of strike on Germany before the midterm elections. An all-out invasion of France wasn’t yet possible, so Roosevelt agreed to Churchill’s proposed lesser invasion in North Africa, pleading with Gen. Marshall, “Please, make it before election day.” Eisenhower, who would lead the attack, thought the African diversion “strategically unsound” and concluded that it would “have no effect on the 1942 campaign in Russia.” If FDR’s generals were unhappy, Stalin was livid. The Soviet leader, with good reason, doubted the sincerity and motives of the Western Allies and resented bearing the full brunt of the German army’s offensives. At the first meeting of the Big Three leaders, in Tehran, Iran, in November 1943, Stalin reminded Churchill of the millions of casualties already sustained by the Red Army. Indeed, later historians would see this period as sowing the seeds for a divided, suspicious, Cold War world that would emerge soon after the German surrender.

Amid the British hesitancy about an invasion of France, the Americans felt a greater sense of urgency. The U.S., unlike Britain, was truly engaged in a two-front war and needed Soviet assistance in the Pacific to avoid massive casualties in the already bloody campaign against Japan. Stalin knew this, and months before the Tehran conference had reminded Roosevelt that “in the Far East … the U.S.S.R. is not in a state of war.” If the Americans wanted future Russian intervention in the Pacific, Stalin made it clear that FDR had to push the British along and deliver a second front soon. That second front was also necessary, many American strategists knew, if the U.S. and Britain were to maintain postwar influence on the continent. One State Department assessment at the time warned, “If Germany collapses before the democracies have been able to make an important military contribution on the continent … the peoples of Europe will with reason believe that the war was won by the Russians alone … so that it will be difficult for Great Britain and the United States to oppose successfully any line of policy which the Kremlin may choose.”

With both these concerns in mind, Roosevelt decided on a relatively sanguine approach to Stalin. Given the strength of the Soviet army, he may not have had much choice. Nevertheless, FDR appeared to acquiesce to Stalin’s postwar influence in Eastern Europe, and again played politics in his negotiations at the Tehran conference. After agreeing to Soviet dominance in the Baltic states, the future of Poland came up. Here, according to official minutes from the conference, Roosevelt explained to Stalin that “there were in the United States from six to seven million Americans of Polish extraction, and, as a practical man, he did not wish to lose their vote.” Therefore, while accepting a Soviet sphere of influence in the region, Roosevelt asked Stalin to delay any decision on Polish frontiers and to make some “public declaration in regard to future elections in Eastern Europe.” Given that the Second World War erupted over the issue of Polish sovereignty, this was a remarkable concession. Then again, while the U.S. had approximately 10 divisions in Europe at the time, Stalin had hundreds more, some of them even then on the very frontier of Poland. It’s unclear how the Western Allies could have then stopped him.

In another remarkable exchange, Roosevelt appeared to placate Stalin, much to the consternation of Churchill. When, over dinner, Stalin proposed that 50,000 German military officers be “physically liquidated” after the war, Churchill rose to his feet and declared, “I will not be party to any butchery in cold blood!” Roosevelt, seeking to lighten the mood, stated, “I have a compromise to propose. Not fifty thousand, but only forty-nine thousand should be shot.” Churchill was furious, but such was the nature, and paradox, of the alliance. In the end, the leaders left Tehran after agreeing to the opening of a second front in France by May 1944, and for a Soviet entrance into the Pacific war soon after the defeat of Germany.

When next the three leaders met, in Yalta, in February 1945, Germany was on the verge of defeat and Russian troops had fought their way to the outskirts of Berlin. Stalin’s divisions dominated Eastern Europe by way of physical presence, and the U.S. was engaged in an increasingly bloody “island-hopping” campaign in the Pacific. There, the Japanese showed no sign of relenting and were fighting to almost the last man in each and every battle. Soviet assistance was thought necessary to shorten the Pacific war. At Yalta the Allies discussed the membership rules for the new United Nations, the partition of Germany, the fate of Eastern Europe, and Soviet participation in the war with Japan.

Here again, Roosevelt appeared to appease Stalin regarding Poland and all of Eastern Europe. The Russian leader made clear that Poland “was a question of both honor and security,” even “one of life and death” for the Soviet Union. Roosevelt replied with a personal note that assured Stalin “the United States will never lend its support in any way to any provisional government in Poland that would be inimical to your interests.” Such a statement appeared to give Stalin a free hand in Eastern Europe, and many later historians would conclude that FDR—perhaps due to his increasingly feeble health—had sold out to Stalin.

The reality was much more nuanced. Roosevelt knew he held the weak hand in Europe. The Red Army already occupied half the continent, and unless FDR was willing to mobilize a few hundred more divisions and order Eisenhower to fight his way to Poland, there was little the president could do to alter the facts on the ground. When the presidential chief of staff, Adm. William Leahy, demurred about the implications of Roosevelt’s note, FDR said, “I know, Bill—I know it. But it’s the best I can do for Poland at this time.” Soon after, he told another associate that, regarding Yalta, “I didn’t say the result was good. I said it was the best I could do.” And it probably was, though that was certainly little consolation to Poles.

In exchange, Stalin promised, again, to declare war on Japan. Roosevelt saw this as the real prize to be gained at Yalta. He told Stalin that he “hoped that it would not be necessary actually to invade the Japanese islands,” if the Soviets attacked in Manchuria, made Siberian air bases available for U.S. bombing of Japan’s cities, and otherwise demonstrated the essential hopelessness of Tokyo’s cause. This was genuinely vital. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated that a Soviet intervention could shorten the Pacific war by a year or more and thus save many American lives. Besides, a shrewd FDR also hoped that focusing Soviet military strength eastward might actually loosen Stalin’s grip on Eastern Europe.

In the final assessment, the Big Three ultimately managed a difficult alliance—built on necessity rather than affinity—to achieve the defeat of both Germany and Japan. This was no small task. The cost of victory was a divided Europe—physically and ideologically. FDR and Churchill weren’t feeble but they were rather realistic in their negotiations with Stalin. Perhaps Roosevelt, ever the charmer and the schemer, had something in mind for future policy pressure on the Soviets, but, with his death just two months after the Yalta Conference, we’ll never know.

Fighting a World War: Paradox and Contradiction

“[The bombing] is inhuman barbarism that has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.” —President Franklin Roosevelt, describing the German bombing of Rotterdam, Holland, in which 880 civilians were killed (1940)

“There are no innocent civilians. It is their government and you are fighting a people, you are not trying to fight an armed force anymore. So it doesn’t bother me so much to be killing the so-called innocent bystanders.” —Gen. Curtis LeMay, U.S. Army Air Corps commander in the Pacific Theater after American planes killed approximately 90,000 civilians in Tokyo (1945)

The Second World War even surpassed World War I in its barbarity. In this second global conflict, civilians would bear the brunt of the fighting, a significant change from the First World War. As the conflict rolled along, the combatant countries increased in desperation and brutality. This was not limited to the Axis Powers or the Communist Soviet dictatorship. To win the war at the least cost in their own people’s lives, the Western democracies would continually dial up the cruelty of their tactics and shift the suffering onto enemy civilians. That, perhaps, was the major contradiction of the Anglo-American war effort. Two ostensible democracies agreed in principle to the humanitarian tenets of the Atlantic Charter, then waged a terror war (especially from the sky) on civilians.

There were other paradoxes and realities that deflated many popular myths about America’s role in the war. For example, though most Americans remember World War II as a time of extreme patriotism and selflessness, in truth the populace did not race as one to the recruiting stations. A strong strain of isolationism remained even after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Indeed, all but a few of the most anti-interventionist congressmen were re-elected in November 1942. Draft deferments were common and coveted from the start. Because married men were exempted from the first draft calls, some 40 percent of American 21-year-olds became betrothed within six weeks! The exemption was later ended, and eventually some 18 percent of families would send a son to the military. Nevertheless, this was a fraction of the commitment seen in other belligerent nations.

The draft itself was controversial and—as in most large, hasty bureaucracies—inefficient and often unfair. The typical GI who liberated Western Europe and the Pacific was 26 years old, 5 feet 8 inches tall and 144 pounds. He had, on average, completed just one year of high school. He took a pre-induction classification test that determined which jobs he was qualified for. Paradoxically, those troopers who were larger, stronger and smarter usually ended up in the Army Service Forces and Army Air Forces. Thus, the typical infantryman who carried a heavy pack and did the bulk of the fighting was shorter and weighed less than his peers in the rear. All told, the U.S. Army’s “tail-to-teeth” ratio—the relative number of support to combat troopers—was 2 to 1, the highest of any army in the war. Proportionally far fewer men in the U.S. Army did the fighting than in Allied or enemy armies.

When U.S. soldiers did fight—at least in Europe—they were often outmatched by the Germans and equipped with gear that was inferior. German tanks, in particular, were superior, and nothing in the American armored arsenal could stand toe-to-toe with the feared Panther and Tiger tanks of the enemy. What the Americans did have was numbers. They made up for inferior quality with mass production of mechanized vehicles. Still, the rule of thumb was that it took five or more American Sherman tanks to overcome a Panther or Tiger tank. German troops were also more battle-hardened and usually more effective in early combat meetings between the two forces. This, too, defies the myth of American superiority and single-handed victory in the war. After all, in late 1944, when the U.S. Army nearly ran out of infantry replacement troops, the Soviets deployed exponentially more divisions’ worth of foot soldiers against the Germans.

The Western democracies also fought a war with such brutality that it contradicted their own principles. This, too, is often forgotten. Strategic air bombing of German (and sometimes French) cities was inaccurate and, beyond the slaughter on the ground, was notoriously dangerous for the flight crews. That’s why, early on, the British shifted to nighttime “area bombing” over more hazardous but somewhat more accurate daytime bombing. At first, the U.S. Army Air Corps recoiled at these tactics, with one senior U.S. officer deploring “British baby killing schemes” that “would be a blot on the history of the air forces of the [allied] U.S.” However, as the realities of the danger and inaccuracy sank in, the Americans, though sticking to daylight bombing, would succumb to the pressure to bomb civilians. By 1944-45, the Army Air Corps was staging massive raids on major cities. A single attack on Berlin killed 25,000 civilians. Ten days later, a combined Anglo-American assault unleashed a firestorm in Dresden that killed 35,000. All told, the British and American air forces killed many hundreds of thousands of German civilians from the air. The fiction that the targets were “strategic,” “military” or “industrial” didn’t stand up under close scrutiny.

Did the bombing work, though? Air power enthusiasts, then and now, are certain that it did and does—that bombing alone can end a war. Nevertheless, in 208 separate postwar studies conducted by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, that military-commissioned organization concluded that bombing had “contributed significantly” but had not by itself been decisive. Even under the heaviest bombing, German economic output tripled between 1941 and 1944, and while the attacks certainly hurt local morale they had “markedly less effect on behavior.” In other words, factory employees kept going to work, soldiers kept fighting and German industrial output actually increased during the war.

The bombing of Japan was even more brutal and more overtly targeted at civilians. When Gen. Curtis LeMay took over the 21st Bomber Command in January 1945, he unleashed a literal firestorm on Japan’s mostly wooden cities. “I’ll tell you what war is about,” he once opined, “You’ve got to kill people, and when you’ve killed enough they stop fighting.” In that spirit, LeMay had his pilots practice and perfect firebombing techniques meant to purposely set off thermal hurricanes that killed by both heat and suffocation as the flames removed oxygen. On the single night of March 9-10, 1945, a massive raid in Japan killed 90,000 men, women and children—some boiled alive within the canals where they had sought refuge—and left 1 million people homeless. In the five months after that night, 43 percent of Japan’s 66 largest cities were destroyed. About a million people died, 1.3 million were injured and 8 million lost their homes.

Working as an analyst on LeMay’s staff in those days was a young officer, Robert McNamara, who would be secretary of defense during the Vietnam War. His job was to carefully study and increase the efficiency of this mass murder. McNamara remembered that LeMay once admitted they probably would have been tried for war crimes had the U.S. lost the war. And, when asked about this more than 60 years later, McNamara concluded that the general had been correct.

The European Theater: Distractions and a ‘Second Front’

America’s war for Europe actually began in North Africa. There, in November 1942, Gen. Eisenhower’s army rushed ashore on the beaches of the Vichy (Nazi-collaborating) French colonies of Algeria and Morocco. Though U.S. commanders and diplomats tried to convince the French troops guarding those beaches to lay down their arms, it came to pass—paradoxically—that in its first major ground combat in the European theater of operations (ETO), U.S. troops killed French soldiers and died at French hands. After 48 hours and hundreds of deaths, the U.S. arranged a general cease-fire with the fascist-sympathizing Adm. François Darlan. An incensed Hitler immediately occupied the remainder of France and forced the Vichy government to “invite” German forces into Tunisia to check the American advance.

In early combat engagements with the Germans, Eisenhower’s untested troops were regularly embarrassed by Gen. Rommel’s battle-hardened veterans. At Kasserine Pass, the first sizable engagement between U.S. and German troops, the Americans were handily beaten. Nevertheless, by March 1943, assaults of Americans from the west and Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s British forces from the east converged to defeat the German-Italian army. The Allies captured some 250,000 Axis prisoners, but many of the best German divisions escaped to Italy. Meanwhile, as the Allies were making this early (if feeble) effort at a second front, the Soviets still were confronting more than 200 Axis divisions in Russia.

Though the American military commanders wanted to strike next at France itself, the Brits—who still provided the majority of divisions in the ETO—convinced Roosevelt to next target the island of Sicily (July 1943), followed by the Italian mainland (September 1943). The Americans insisted, however, that all new divisions sent to the ETO be diverted to Britain in preparation for the invasion of France. Thus, the campaign in Italy—which the U.S. commanders didn’t want to fight in the first place—would have to proceed on a shoestring. The Germans sent just 16 divisions to Italy, and that force, under the command of the brilliant Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, used the peninsula’s rugged terrain to tie down two Allied armies in an indecisive battle of attrition for nearly two years. As the historian David M. Kennedy strongly concluded, this was a campaign “whose costs were justified by no defensible military or political purpose,” except, perhaps, to assuage Churchill’s hesitancy about the France invasion and his career-long obsession with securing the Mediterranean Sea.

When the Allies hit the Italian mainland at Salerno, the U.S. commander, Gen. Mark Clark, unwisely chose to forgo the customary preliminary bombardment—hoping to exploit the element of surprise—and as a result a vicious German counterattack almost drove the Americans back into the sea. Only emergency naval gunfire support saved the beachhead. What followed was five months of grinding attritional warfare. Unable to make any significant northward progress, Clark requested another amphibious assault—which controversially delayed the France invasion again—on the beaches of Anzio, north of the main German defensive lines. Though little resistance was met on the shoreline, Gen. John Lucas hesitated long enough for the Germans to mount another counterattack. Lucas’ pathetic force was thus pinned down on a narrow beachhead for months, and the entire Italian campaign again ground to a halt. When, in the late spring, the Allied forces finally broke through the German defense, Gen. Clark struck out for the political prize of Rome rather than cutting off the main German force. This allowed Kesselring to escape and set up a new series of defensive lines to the north. Then the whole process repeated itself for nearly a year.

Kesselring’s small force held out until almost the end of the war. The needless sideshow in Italy cost 188,000 American and 123,000 British casualties. All the while, Kesselring held the two Allied armies at bay with fewer than 20 divisions, hardly any of which had been transferred from the Eastern Front. Stalin and the Soviets were enraged by the Allied foray into Italy, especially when the Salerno and Anzio landings further delayed the cross-channel invasion of France. He wrote to Roosevelt that the latest delay “leaves the Soviet Army, which is fighting not only for its country, but also for its Allies, to do the job alone, almost single-handed.” Stalin then hinted at how this frustration could presage later (Cold War-style) conflict, adding, “Need I speak of the dishearteningly negative impression that this fresh postponement of the second front … will produce in the Soviet Union—both among the people and in the army?” Given the quagmire in the Mediterranean, the Soviet leader had a point.

While the battles raged in North Africa and Italy, the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO)—strategic bombing from the air—was the closest thing to a second front available in Northwestern Europe. This controversial campaign was both dangerous to airmen—casualty rates among bomber crews were among the highest in the war—and highly destructive to civilians. Nonetheless, both British and American air commanders hoped to prove that their service’s contribution could win the war single-handedly. It was not to be so. What did occur was a massacre of German civilians. This shouldn’t have been surprising. The Italian Giulio Douhet, the principal air war theorist of the 1920s, had long argued that in modern warfare civilian targets should be fair game. As he famously wrote, “The woman loading shells in a factory, the farmer growing wheat, the scientist experimenting in the laboratory” were targets as legitimate as “the soldier carrying his gun.” Ironically, this was the precise argument al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden would make years later in justifying his 9/11 attacks on the U.S. homeland.

Some of the devastation among civilians was inevitable, given the technological limitations of 1940s aircraft; military decisions growing out of those limitations greatly increased death on the ground. A British bomber command study in 1941 concluded that only one-third of bombers made it to within five miles of their targets. Thus, in 1942, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) directed that bombers henceforth focus on targeting “the morale of the enemy civil population.” The Brits euphemistically referred to this as “area bombing.” It amounted to premeditated murder from the skies. At first, the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) shunned the British approach, but soon the Americans were mimicking the RAF tactics. The war had changed the hearts of many leaders. Back in 1940, President Roosevelt was horrified by a German air attack on Rotterdam that killed some 800 civilians. He called the incident “barbaric.” By 1943-44, the RAF and USAAF were sometimes killing thousands of civilians per day.

The airmen of the USAAF faced their own horrors. Accidents took nearly as many lives among American airmen as combat actions. In 1943, the USAAF lost 5 percent of its crewmen in each mission, casualties so appalling that two-thirds of American airmen that year did not survive their required quota of 25 missions. Despite this human cost, and despite the optimistic predictions of the airpower enthusiasts, strategic bombing alone could not substitute for a ground-level second front in France.

On June 6, 1944—D-Day—nearly two years and seven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, British and American troops rushed ashore on the beaches of Normandy, France. The invasion was coordinated with an even larger Russian offensive, Operation Bagration, which shattered many German divisions and caused 350,000 Axis casualties. Initially, at least, the Normandy invasion met with far less success. Though the Western Allies managed to get tens of thousands and then hundreds of thousands of troops ashore, it took more than a month to break out of the stalemate at the beachhead. Finally, in Operation Cobra (July-August 1944), a massive aerial bombardment followed by Gen. George Patton’s armored spearhead, the Anglo-American armies annihilated 40 German divisions and inflicted 450,000 casualties. For a moment it looked as though the war would be over by Christmas. The Intelligence Committee in London predicted that “organized resistance … is unlikely to continue beyond December 1, 1944, and … may end even sooner.” It was not to be.

The Allies still had only one functioning French port available to them, and this slowed vital logistics. Fuel and food simply couldn’t keep up with Patton and Montgomery’s mechanized thrusts. In September 1944, Operation Market Garden, the brainchild of Gen. Montgomery, kicked off with a three-division parachute assault to secure key bridges on the path to Germany. The attack stalled, and Montgomery’s tanks couldn’t reach the final bridge in time. The long-shot gamble hadn’t worked. Market Garden cost thousands of Allied casualties and then petered out, leading to a winter stalemate. The Germans still had a lot of fight in them and held strong for two more months, inflicting 20,000 American casualties at the indecisive Battle of the Huertgen Forest, which occurred along the Belgian-German border.

Then, in December, Hitler launched one final mad offensive to divide the Allied armies and seize the vital port of Antwerp in Belgium. The Americans were initially pushed back, creating a “bulge” in the Allied lines. Then Hitler’s gamble ground to a halt when the skies cleared and Allied planes could again pound the vulnerable Germans from the air. Even though the Battle of the Bulge came as a shock to the Allies, and turned out to be the bloodiest single fight for the Americans in the ETO, Hitler had expended his last reserves and suffered 100,000 more casualties. By April, the Soviets were fighting on the outskirts of Berlin, Eisenhower’s troops had breached Germany’s Western Wall, and American and Russian troops were linking hands along the River Elbe west of Berlin. In the first week of May, Hitler committed suicide and Germany surrendered. The date, May 8, would be forever known as Victory in Europe (V-E) Day.

The Pacific Theater: War Without Mercy

The war in the Pacific wasn’t supposed to occur at all. Containment and deterrence of the Japanese was supposed to delay, perhaps avoid, a war in the Pacific. “Germany First” was the strategy agreed upon by the British and American senior commanders well before the U.S. entered either theater of war. Nonetheless, in a calculated, if ill-advised, gamble, the militarists atop the Japanese government decided on an all-out surprise attack meant to destroy the American Pacific fleet in hopes of forcing Washington into a peace settlement and economic concessions. The architect of the attack, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, knew the risks involved. He had studied at Harvard, later served as a naval attaché in Washington and held a deep respect for America’s vast industrial potential.

Yamamoto had, in the recent past, been a voice for moderation and argued against the surprise attack. He knew that Tokyo would have only a small window for victory and that Japan, if the war dragged on, would eventually be overwhelmed by the now-roused American “sleeping giant.” “If I am told to fight regardless of the consequences,” Yamamoto had warned the Japanese prime minister, “I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year.” How prescient the admiral would prove to be.

At first Yamamoto’s gamut seemed to pay off. By 10 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, the day of the Japanese attack, 18 U.S. ships, including eight battleships, had been sunk or heavily damaged, more than 300 U.S. aircraft destroyed or crippled and more than 2,300 sailors and soldiers killed. The Americans were caught by surprise, but—in a stroke of luck—none of the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers, which would prove more valuable than battleships in the coming war, were at Pearl Harbor that morning. All survived to fight another day.

Still, Yamamoto and the Japanese military did indeed “run wild” in the six months following Pearl Harbor. British, Dutch and American possessions—Hong Kong, Guam, Wake Island, the East Indies and Indochina—fell one after the other to the Japanese blitz. On Feb. 15, 1942, in what is widely considered the worst defeat in British military history, a garrison of 85,000 surrendered to a Japanese force barely half its size. The attack on the U.S. contingent in the Philippines, commanded by the implacable, demagogic Gen. Douglas MacArthur, had begun Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the Pearl Harbor attack. Though MacArthur had been warned of the possibility of an imminent Japanese attack, he unforgivably allowed nearly his entire air force to be destroyed on the ground. Without an air corps and with the U.S. Pacific fleet crippled, the fate of the Philippines was sealed.

MacArthur had been a strong combat leader in World War I, but he gained a reputation as a shameless self-promoter. After the Japanese attack on the Philippines he was given the derisive nickname “Dugout Doug,” which implied he was making himself safe in his tunnel headquarters while his men were dying under the Japanese assault. He would visit only once with his soldiers during their fierce battle on the Bataan peninsula before Roosevelt ordered him to evacuate to Australia.

On March 12, MacArthur left Gen. Jonathan Wainwright in command of the doomed garrison and left with his family and personal staff on a small patrol boat. In what seemed an obvious PR stunt and face-saving measure, Congress conferred the Medal of Honor on him. By May 6, roughly 10,000 American and 60,000 Filipino soldiers had surrendered to the Japanese. Dwight Eisenhower, a former subordinate of MacArthur, was less than impressed with the senior general’s performance. In his diary that night, Ike wrote that “[the Philippine garrison] surrendered last night. Poor Wainwright! He did the fighting. … [but MacArthur] got such glory as the public could find in the operation. … General Mac’s tirades to which … I so often listened in Manila, would now sound as silly to the public as they did to us. But he’s a hero! Yah.”

A tragedy followed. The Japanese army in the Philippines, itself undersupplied and malnourished, wasn’t prepared to accept 70,000 prisoners. Furthermore, in a clash of cultures, the Japanese—who subscribed to a Bushido code that some experts have described as “a range of mental attitudes that bordered on psychopathy” and which “saw surrender as the ultimate dishonor”—brutalized the captives. In an 80-mile forced march, the prisoners were denied water, often beaten and sometimes bayoneted. Six hundred Americans and perhaps 10,000 Filipinos died on the “Bataan Death March.” Thousands more wouldn’t survive the following four years of captivity in filthy camps.

The Americans and British had surely taken, in the words of Gen. “Vinegar” Joe Stilwell, “one hell of a beating.” Even so, as Yamamoto had feared, the tide quickly turned. When the Japanese fleet headed for tiny Midway Island, an American possession to the west of Pearl Harbor, to finish off the remaining U.S. ships, the Americans—thanks to “Magic,” their program for cracking the Japanese naval code—were ready. American flyers sank four of Japan’s six carriers at the loss of only one U.S. carrier, shifting the momentum of the entire Pacific war in a single engagement. From this point forward, U.S. industry would pump out carriers, submarines, cruisers and aircraft at a rate exponentially higher than Japan’s. For example, whereas the Japanese constructed only six additional large carriers throughout the war, the U.S. fielded 17 large, 10 medium and a stunning 86 escort carriers.

The Americans now went on the offensive, albeit slowly at first. Naval commanders preferred a drive straight across the Central Pacific, “island-hopping” from one Japanese garrison to the next, but MacArthur insisted on a campaign through the Southwest Pacific from Australia, to New Guinea, and finally to the Philippines—to which MacArthur had famously vowed to return. Roosevelt, the astute politician, split the difference in supplies and troops and decided on a less efficient two-track advance. Adm. Chester Nimitz and the Marine Corps would lead in the Central Pacific while MacArthur and the Army moved slowly toward the Philippines.

The first stop for Nimitz was the distant Solomon Islands. There, on the island of Tulagi, the Marines received their first—but certainly not last—taste of fierce Japanese defensive tactics. Only three of Tulagi’s 350 defenders surrendered. Others were incinerated when lit gasoline drums were thrown into their concealed caves. On nearby islands, only 20 of 500 defenders surrendered. All told, 115 U.S. Marines died in these fights, establishing the approximately 10-1 ratio of casualties that would prevail throughout the long Pacific war. Nevertheless, the Japanese still had some offensive potential and in the Battle of Savo Island inflicted the worst-ever defeat of the U.S. Navy on the high seas. Nearly 2,000 American sailors were killed or wounded. Still, the Japanese had failed to ward off the U.S. invasion of the island Guadalcanal in the Solomon chain. Thus began one of the strangest campaigns of the Pacific war—perhaps the only such battle in which Americans were defending an island and did not, as of yet, enjoy total air and naval superiority. It was a long, tough campaign and stretched the morale and resources of the U.S. soldiers and Marines engaged.

The brutality and fanaticism of both sides were again on display. When American Marines ambushed an attacking force, 800 Japanese died and only one surrendered. And, after some of the wounded tried to kill approaching American medics, the Marines slaughtered every surviving Japanese soldier. By October 1942, the U.S. garrison had been reinforced, expending to some 27,000; by year’s end the number would be 60,000. The joint Army/Marine force could then take the offensive. Still, in four more months of bloody fighting the Americans suffered nearly 2,000 more casualties. At that rate, U.S. casualties could grow to cataclysmic levels if every Japanese island garrison were assaulted. It was thus decided to “hop” the islands, bypassing most and securing only vital platforms for airfields and logistics hubs. Most of the other Japanese garrisons were left to rot, their supply lines to Tokyo severed.

In the Southwest Pacific, MacArthur first helped the Australians defend Papua, though the ever-charming general won few friends there when he described the more than 600 Australian dead on that island as “extremely light casualties,” indicating “no serious effort.” MacArthur’s own force suffered heavy casualties when he recklessly wasted troops to seize Buna and Gona, but it did, by December 1942, end the Japanese threat to Australia. In March 1943, MacArthur’s air chief, Gen. George Kenney, successfully organized his planes in a spectacular attack on a Japanese reinforcing convoy of ships. After the bombers sank the troop transports and a few destroyers, American fighter planes and patrol boats strafed and machine-gunned the floating survivors in a veritable war crime. Such was the mercilessness of the Pacific war. Then, in April 1943, when the “Magic” code showed that Adm. Yamamoto intended to fly in and visit his troops at the front, U.S. Navy flyers intercepted his airplane, sending the admiral to a warrior’s death.

For the rest of the war, U.S. Marines and soldiers “hopped” from one island to the next, suffering horrific casualties whenever they needed to seize, and not bypass, a stronghold. Early on, U.S. commanders began to worry about the potential catastrophe of invading Japan itself, since with each step to the home islands the defenders fought even more tenaciously. For example, on the tiny island of Tarawa—about the size of New York City’s Central Park—5,000 Japanese defenders inflicted 3,000 casualties on the attacking Marines. That attrition rate was simply unsustainable for the Americans. The resolve of the Japanese soldiers was demonstrated on island after island. Almost none became prisoners, partly because U.S. troops decided to stop taking any, but mainly because to surrender was to the Japanese the ultimate dishonor. Indeed, the Japanese army’s Field Service Code contained no instructions on how to surrender, stating flatly that troops should “[n]ever give up a position but rather die.”

So it was that Nimitz drove straight west across the Central Pacific and MacArthur “hopped” to the northeast of Australia. When Nimitz’s troops reached the island of Saipan, the final 3,000 desperate Japanese defenders, some wielding only knives tied to bamboo poles, suicidally rushed the American lines screaming the battle cry “Banzai!” They were wiped out. Then on Marpi Point, at the northern tip of the island, Japanese women and children leaped to their deaths off the 250-foot cliffs. The horrified American interpreters shouted through bullhorns in an attempt to coax at least some to choose surrender over suicide. Still, thousands jumped, and when the battle finally ended, the Americans had suffered an additional 14,000 casualties.

In July 1944, President Roosevelt visited his two Pacific commanders—Nimitz and MacArthur—in Hawaii to discuss strategy. When Nimitz and members of the president’s staff suggested that it was perhaps best to bypass the well-defended Philippines, MacArthur loudly objected. Should their Filipino “wards” not be liberated, MacArthur boldly warned FDR, “I dare say that the American people would be so aroused that they would register most complete resentment against you at the polls this fall.” Only a man like MacArthur would dare serve up such an overt political threat. Nonetheless, the president made another “non-decision”; both Nimitz and MacArthur would drive forward as planned and the Philippines remained on the target list.

The war had permanently turned against the Japanese by late 1944. The issue was settled, and only the final casualty counts were in question. U.S. submarines cut Japanese oil and other supplies to a trickle. Japan was in danger of being starved. Then, in the epic Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Japanese fleet was all but destroyed once and for all. And, when U.S. rescue vessels approached the thousands of floating Japanese survivors, most submerged themselves and chose drowning over capture. Leyte Gulf marked the end of an era of ship-on-ship gunnery duels. Naval airpower was now the dominant force, and no nation would ever again build a battleship. Moreover, though the Japanese fleet was forever crippled, it was at Leyte that the remaining Japanese naval aircraft began their suicidal “kamikaze” attacks, purposely flying into American ships.

On Jan. 9, 1945, MacArthur landed more than 10 divisions in the Philippines. Yet, as predicted, his opponent, Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, along with a large garrison, put up a stout defense. Retreating into the jungles and mountains of the vast Philippine interior, Yamashita executed a costly delaying action for months in a campaign that resembled the tough fight in Italy. In the end, the Philippine invasion was a costly operation that historian David M. Kennedy has concluded “had little direct bearing by this time on Japan’s ultimate defeat.”

In the Central Pacific theater, the next stop was the volcanic island of Iwo Jima. Here, despite 72 days of aerial bombardment and three days of naval gunfire, the 21,000 Japanese defenders managed to inflict 23,000 casualties on the U.S. Marines. Almost none of the defenders surrendered, and more than 20,000 died—many incinerated in their bunkers by tank-mounted flamethrowers. The final battle in the Central Pacific was on the island of Okinawa. Though the locals were racially distinct, the Japanese considered them part of the home islands. As had Yamashita’s force in the Philippines, the 77,000 Japanese defenders decided not to contest the landing sites and chose to wage a lengthy battle of attrition inland. The Japanese knew they couldn’t win; they merely hoped to buy time so their brethren could better fortify the homeland.

On Okinawa, the American invasion force rivaled the numbers put ashore in Normandy, France. So intense was the combat that the senior American commander, Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, was himself killed. Toward the end of the desperate, doomed defense, Japanese volunteers—in an early form of suicide bombing—would rush the Americans with satchel charges strapped to their bodies. The U.S. soldiers and Marines referred to them as “human bazookas.” The suicidal tactics also proliferated offshore, where waves of kamikaze aircraft sank 36 ships, damaged 368 more and inflicted some 10,000 casualties.

In June, the final 6,000 Japanese defenders, armed with sidearms and spears, made a final “Banzai” charge. The Japanese commander ordered an aide to behead him once he had ritually thrust a hara-kiri dagger into his own belly. When it was all over, 70,000 Japanese soldiers were dead along with 100,000 Okinawan civilians. The Americans suffered 39,000 combat casualties and 26,000 more non-combat injuries, for a total casualty rate of 35 percent. Thus, with Okinawa and Iwo Jima secured, Hitler dead and Germany having surrendered, nervous American generals and admirals wondered what sort of carnage awaited them in Japan itself. The question was whether such an invasion would be necessary.

Original Sin: Race Rears its Ugly Head at Home and Abroad

“I’m for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska, and Hawaii now and putting them in concentration camps. … Damn them! Let’s get rid of them now!” —U.S. Rep. John Rankin of Mississippi, on Dec. 15, 1941

“Their racial characteristics are such that we cannot understand or trust even the citizen Japanese.” —Secretary of War Henry Stimson in 1942

Racial caste and racism constitute, undoubtedly, the original sins of the American Experiment. In each overseas war that the U.S. has waged, that sin didn’t halt at the shoreline. Rather, America’s racist baggage was and is always along for the trip. This was especially true during the Second World War, a war ostensibly waged for democracy. Both at home and abroad the U.S. failed to live up to its values and treated African-Americans and the Japanese in particular with a brutal form of racial animus.

No description of the American homefront in World War II is complete without a brief account of the internment of Japanese-Americans on the West Coast, many of them native-born citizens. Essentially, over 100,000 of these people were uprooted from their homes, turned into internal refugees and then imprisoned in sparse inland camps for the duration of the war. This treatment of the Japanese-Americans, ostensibly motivated by fear of internal subversion (of which almost none was eventually found), was unique to this Asian minority. Even though Nazi Germany was considered the greater global threat and the first military priority in the stated “Germany-First” strategy of the Allies, no substantial class of German-Americans or Italian-Americans was interned. That only Japanese were so treated should not come as a surprise. There had long been racial hatred of the Japanese in California, and all immigration from Japan was shut off through the federal Immigration Act of 1924.

So it was on Feb. 19, 1942, that Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, sealing the fate of 112,000 Japanese-Americans, 79,000 of whom were citizens. They were first placed under a curfew, and then, with only what they could carry, they were moved to camps in a number of states. There they lived under guard behind barbed-wire fences for years. In many cases those who were interned had sons fighting for the country that had imprisoned them. Indeed, in a bit of irony, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese-American unit, was one of the most decorated outfits in the entire war.

Plenty of Americans were appalled by internment, even at the time. The famed photographer Dorothea Lange took photos of the removal process. She had been commissioned to do so by the War Relocation Authority, but once the photos were developed the government chose to lock them away in archives labeled “IMPOUNDED” for decades. Lange herself disagreed with the president’s executive order, and, according to her assistant, “She thought that we were entering a period of fascism and that she was viewing the end of democracy as we know it.” Despite personal appeals from sympathetic citizens, Japanese-Americans found no relief from the U.S. Supreme Court, which, in an infamous 1944 decision, Korematsu v. United States, upheld the order in a 6-3 decision.

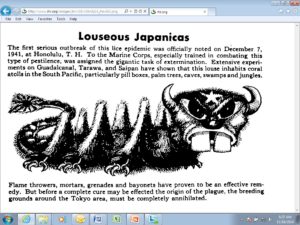

Unlike the war in Europe, the Pacific war was a race war, one that cut both ways. In the Pacific theater, Japanese troops and civilians were treated far worse than America’s German or Italian enemies. Some of this mistreatment may be explained by the unwillingness of Japanese troops to surrender, Japan’s mistreatment of American prisoners of war and the ongoing anger over the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Still, generations of anti-Asian racism did seem to play a role in the unique animus toward the Japanese enemy. The hatred on both sides of the Pacific conflict was so intense that the esteemed historian John Dower called it a “war without mercy.” Neither side saw the other as fully human. As one Marine on Guadalcanal lamented, “I wish we were fighting against Germans. They are human beings, like us. … But the Japanese are like animals.” Indeed, it was not atypical for the Japanese people as a whole to be depicted, especially by war’s end, as vermin to be exterminated. Nor were the Japanese above perpetuating their own intra-Asian philosophy of racism. They too were a proud, chauvinist people with a great deal of racial nationalism animating their wartime actions.

Still, there was something unique about the fighting in the Pacific. Though most Americans loathed the Nazis, it was only in the Pacific theater that it became commonplace for U.S. servicemen to shoot prisoners, strafe lifeboats, mutilate bodies, make necklaces out of ears or teeth, and fashion letter openers from Japanese bones (one of which was mailed to FDR, who refused the gift). As historian John Dower wrote, “It is virtually inconceivable that teeth, ears, and skulls could have been collected from German or Italian war dead and publicized in the Anglo-American countries without provoking an uproar.” Prisoner mistreatment also defined the Pacific war. Some 90 percent of captured Americans reported being beaten, a typical prisoner lost an average of 61 pounds and more than a third died in captivity. In Europe, by contrast, 99 percent of imprisoned Americans survived the war. In response to this mistreatment and especially after several groups of Japanese attempted ambushes in surrender ruses, U.S. troopers turned to an informal policy of shooting all prisoners.

Propaganda on both sides depicted the “other” as racially inferior and subhuman. Japanese schoolbooks instructed students that they, as Japanese, were “intrinsically quite different from the so-called citizens of Occidental countries,” who were depicted as weak and overly materialistic. In the U.S., wartime cartoons—including animated cartoons by leading filmmakers such as Warner Bros.—portrayed the “Japs” as buck-toothed savages and bespectacled lunatics. And, in Frank Capra’s famous “Why We Fight” film series—which was mandatory viewing for all soldiers in basic training—the narrator instructed the viewer that all Japanese were like “photographic prints off the same negative.” Furthermore, the senior Navy admiral, William “Bull” Halsey, publicly defined his mission as to “Kill Japs, kill Japs, and kill more Japs,” vowing that after the war the Japanese language would be spoken only in hell. Overall, while the U.S. government depicted war with Germany and Italy as a war against fascism or Nazis, in the Pacific the war was distinctly waged against the Japanese as a people. This alone surely contributed to the brutality of the fighting.

* * *

Dear Lord, today I go to war: To fight, to die, Tell me what for?

Dear Lord, I’ll fight, I do not fear, Germans or Japs; My fears are here. America! —“A Draftee’s Prayer,” a poem in The Afro-American, a black newspaper, in January 1943

The America that went to war in December 1941 was still a Jim Crow America. The United States fielded a Jim Crow military, manufactured with a Jim Crow industry and policed the homefront with Jim Crow law enforcement. Ironically, a nation that purported to fight against Nazi racism and for human dignity did so at the time in which nearly all public aspects of American life remained segregated. The war did, however, begin to change America’s racial character, setting off one of the great mass migrations in U.S. history as blacks left the South for Northern industrial plants or induction into the military.

Throughout World War II, blacks served in segregated units led by white officers. In the Army they were usually relegated to support duties and menial labor. They were at first denied enlistment in the Army Air Corps or U.S. Marines altogether. In the Navy they worked only as cooks and stewards. (The Naval Academy at Annapolis had yet to have a single black graduate!) Northern blacks had to deal with the double indignity of serving under white officers in (primarily) Southern mobilization camps. In such locales, it was not uncommon for black troops to be denied service in restaurants that gladly served German and Italian POWs. And, as in World War I, many uniformed African-Americans (seen as “uppity blacks”) were lynched.

The vibrant black press recognized all this as a problem from the very start and pushed hard for racial integration and equality in public and economic life. The Crisis newspaper editorialized that “[a] Jim Crow Army cannot fight for a free world.” While philosophically correct, this proved to be practically untrue. Some African-Americans, understandably, refused to serve. One black man from the Bronx wrote to President Roosevelt that “[e]very time I pick up the paper some poor African-American soldiers are getting shot, lynched, or hung, and framed up. I will be darned if you get me in your forces.”

Some progress was made when FDR mandated equal employment practices in war industries in the face of black labor leader A. Philip Randolph’s threat to march 100,000-plus African-Americans on Washington. Eleanor Roosevelt, well known as a civil rights proponent, had arranged for Randolph to meet with the president, and the result was Executive Order 8802, which prohibited racial discrimination in defense-related industries. On other issues, however, Roosevelt caved in to his Southern Democratic supporters. During the 1944 presidential election, progressive congressmen hoped to guarantee black soldiers the right to vote, something they were denied in their home (mostly Southern) states. However, FDR—always politically conscious—acceded to his party’s Southern wing and left enforcement of voting laws, even for soldiers, to the individual states, with obvious consequences. So, huge numbers of black draftees were fighting and dying for a country in which they could not vote.

Many blacks pointed to the hypocrisy of such measures and organized to press for reform. They took to calling their goals the “Double V” Campaign, meaning victory over the Axis and victory at home against segregation and Jim Crow. The Double V philosophy also often had international components, demonstrating solidarity with black and brown colonized peoples around the world. As the black sociologist Horace Cayton wrote in the Nation magazine in 1943, “To win a cheap military victory over the Axis and then continue the exploitation of subject peoples within the British Empire and the subordination of Negroes in the U.S. is to set the stage for the next world war—probably a war of color.” Indeed, quite a few such wars of colonial independence did break out in the decades following the surrender of the Axis.

Violence also plagued military camps and cities on the homefront. When blacks attempted to move into a Detroit public housing project, whites barricaded the streets. A riot broke out and 6,000 federal troops marched on the city in June 1943. That August, another race riot broke out in response to rumors of police violence in Harlem in New York City. Six people were killed, and 600 were arrested. Riots cut both ways. In Mobile, Ala., white shipyard workers rioted over the influx of black workers and the promotion of some African-American welders. Eleven blacks were seriously injured. In Beaumont, Texas—a town plagued by housing and school shortages—white mobs rampaged through black neighborhoods, killing two and wounding dozens.

In the face of the domestic violence and prejudice against blacks in the military, some African-American troops served with great distinction in the war. One such decorated unit, the all-black 761st Tank Battalion, fought in Normandy under Gen. Patton. The fiery Patton sent them straight to the front with dignity, exclaiming: “I don’t care what color you are, so long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sonsabitches.” No doubt, such unit actions, combined with black migration to the North, and homefront activism did, slowly, shift the needle on civil rights in America. Though a meaningful civil or voting rights bill would have to wait for two decades, President Harry Truman, in 1948, three years after the war’s end, finally ordered full desegregation of the U.S. armed forces. It was a small victory, but a victory nonetheless.

Dropping ‘The Bomb’: The Atomic Weapons Debate

“Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time. … I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal. … But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you’re not a good soldier. …” —Gen. Curtis LeMay, U.S. Army Air Force commander in the Pacific theater

One of the greatest and most terrible projects of World War II was the production of the atomic bomb and the ushering in of the Nuclear Age. In the end, for better or worse, the United States won the race to harness atomic energy. That it did so, ironically, was at least in part due to Hitler’s persecution of German Jews, including Jewish physicists, dozens of whom fled to America and worked on the secret Manhattan Project to build and test the bomb. German racial biases also derailed their own (eventually canceled) atomic program after Hitler took to calling nuclear physics “Jew physics.” By 1945, the U.S. military had developed atomic bombs capable of destroying entire cities. The scientists involved—many of whom actually were pacifists—had unleashed upon the world a destructive weapon that could not be stuffed back into Pandora’s box.

The question now, with the Pacific war still raging, was whether to use the A-bomb on Japanese cities. In the generations since the decision to drop the two bombs, a great debate has occurred among scholars and laymen alike over whether it was necessary or right to do so. After all, many Americans find it disturbing to note that the United States is the only nation ever to use such a weapon in war. The debate centers on the purported justification, or motive, for dropping the bombs. Most agree that the prime motivation was to avert the massive American (and Japanese) casualties expected in an invasion of the Japanese home islands. Some analysts have overestimated the supposed casualty projections—throwing around numbers of up to 1 million American soldiers—to argue that the no-warning atomic bombings were ethically excusable. However, estimates by top military authorities varied from Gen. Marshall’s low of 63,000 to Adm. Leahy’s 268,000. Whichever estimate one chooses, there is no doubt that one deciding factor was fear of high casualties—especially after U.S. troops had suffered a killed/wounded rate of 35 percent against Japanese defenders on Okinawa just months before.

But were the only options the A-bomb and an invasion? This question hinges on Roosevelt’s earlier proclamation that the Allies would accept only the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis Powers. This unqualified demand limited American options for closing the Pacific war and made an invasion of the home islands seem inevitable. Still, even at the time, there were dissenting voices on the issue. Roosevelt’s chief of staff, Leahy, expressed “fear … that our insistence on unconditional surrender would result only in making the Japanese desperate and thereby increase our casualty lists.” Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy added, “We ought to have our heads examined if we don’t explore some other method by which we can terminate this war than by just another conventional attack.” McCloy listed as alternatives giving the Japanese a warning (or demonstration) of the bomb prior to dropping or modifying the unconditional-surrender demands. In fact, the latter might not have proved too difficult.

In reality, by June 1945, Emperor Hirohito had asked his political leaders to examine other methods (besides a fight to the finish) to end the war. As it turned out, within Japan serious consideration was given to such peace entreaties, and Tokyo reached out through Soviet interlocutors to propose a qualified peace. The main Japanese demand—to which the U.S. would eventually accede!—was to maintain the emperor as the head of state.

Either way, by summer 1945 the Japanese were beaten. They were confined to their home islands, could barely supply their main army in China (an army that would soon be attacked by the Soviets) and had no navy left to speak of. To be clear, they no longer posed any serious offensive threat to the United States. Therefore, couldn’t an invasion be avoided, and a simple naval blockade be continued until Japan surrendered? Perhaps. Then again, given the extreme defense put up by Japan’s soldiers throughout the war, it’s also plausible that mass starvation might set in before the enemy capitulated. It’s difficult to measure the potential casualty rates and ethical considerations of this alternative to dropping the bomb.

All of this amounts, in the end, to counterfactual speculation. The reality, as historian John Dower convincingly demonstrates, is that the eventual choice to drop two A-bombs on Japan amounted to a “non-decision.” Besides one petition against the no-warning use of the bomb initiated by some prominent scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, there’s no evidence that any senior policymakers—including Truman—ever seriously considered not dropping the weapon on civilians. Secretary of War Stimson and Manhattan Project leader Gen. Leslie Groves each remember that the final meeting to discuss dropping the bomb lasted less than 45 minutes. Truman later wrote, “Let there be no mistake about it, I regarded the bomb as a military weapon and never had any doubt that it should be used.” Here we must understand that these officials and decision makers led a nation at war that had fire-bombed women and children from the sky as a matter of course. This, they felt, was necessary and proper. By the time the final decision was made, nearly 1 million Japanese and several hundred thousand German civilians had already been killed in conventional bombings. The dropping of the two atomic bombs, then, was in a sense a non-decision; however, it is one with which the world has had to live forever after.

None of this should read as ethical relativism or historical apologetics. There were plenty of senior officials then and soon afterward who opposed or lamented the use of the A-bombs. Former Ambassador to Japan Joseph Grew argued that the U.S. should agree both to retention of the emperor and to eliminate the demand for unconditional surrender. Secretary of War Stimson thought that contrary to public misconception “Japan is susceptible to reason” and might soon surrender if the United States agreed that the emperor would remain. Key military figures from the war also opposed the bomb’s use. Adm. “Bull” Halsey—never known as a soft man—wrote, “The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment. … It was a mistake ever to drop it … [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out, so they dropped it. … It killed a lot of Japs, but the Japs had put out a lot of peace feelers through Russia long before.” Gen. Eisenhower, meanwhile, wrote in his memoirs: “[Upon hearing the bomb would be dropped] I had … a feeling of depression and … voiced … my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was … no longer mandatory … to save American lives.”

Nevertheless, Truman did drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (140,000 dead) and Nagasaki (70,000 dead) before Emperor Hirohito declared to his advisers, “I swallow my own tears and give my sanction to the proposal to accept the Allied proclamation.” Japan surrendered soon afterward, and, under direction from the emperor himself, there was no resistance to military occupation from a populace that quickly took on pacifistic qualities. Meanwhile, the emperor was allowed to keep his ceremonial position. The American people had reached V-J Day.

* * *

“The problem after a war is with the victor. He thinks that he has just proved that war and violence pay.” — A.J. Muste, a noted pacifist, in 1941

World War II altered the planet forever. It was the bloodiest war ever fought between human beings. It built the foundation for a new world, for better or worse. Yet there are tragic ironies inherent in the Allied endeavor. The Western democracies went to war in response to the invasion of Poland, way back in 1939; still, at war’s end the Allies grimly acceded to the domination of that same Polish state by one of the Allied Powers, the Soviet Union. Their willingness—even if they had no real choice—to substitute an authoritarian Soviet state for a German Nazi state in Eastern Europe demonstrates what should have been obvious all along: Britain and France didn’t really fight for democratic sovereignty but, rather, for self-interest, for the balance of power. The Allies ended the war with a divided Europe, half of which would be undemocratic after all, setting the stage for a new and deadly Cold War.