American History for Truthdiggers: Liberty vs. Order (1796-1800)

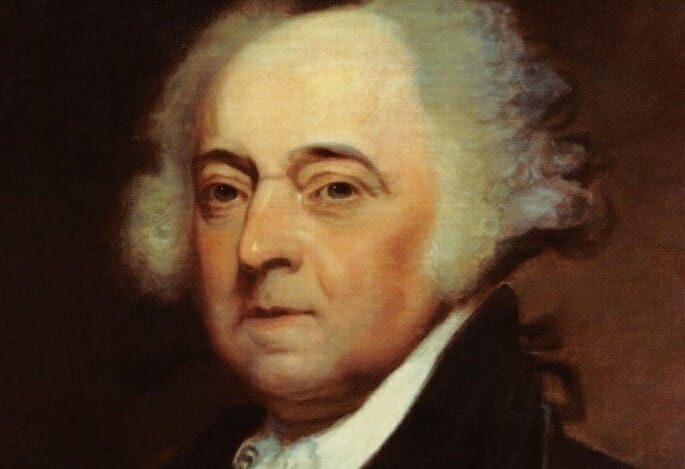

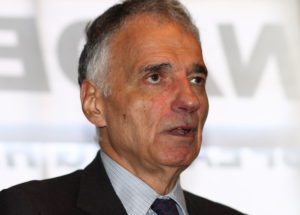

Why did the Federalist and Republican factions each view its opponents as existential threats to the new nation during the Adams administration? A complicated man: John Adams, the second president of the United States, in a painting by Asher B. Durand.

A complicated man: John Adams, the second president of the United States, in a painting by Asher B. Durand.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 10th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 10 of “American History for Truthdiggers.” / See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9.

* * *

“Liberty, once lost, is lost forever.” —John Adams in a letter to his wife, Abigail (1775)

“[A social division exists] between the rich and the poor, the laborious and the idle, the learned and the ignorant. … Nothing, but force, and power and strength can restrain [the latter].” —John Adams in a letter to Thomas Jefferson (1787)

Two quotes from the same person. Barely a decade between the two utterances. How can a man be so conflicted? John Adams, who helped lead the revolution against British “tyranny,” would later become a president apt to suppress dissent and restrict a free press at home. Well, Adams was a complicated man, and the United States was—and is—a complicated nation.

As John Adams succeeded the quintessential American hero, George Washington, becoming the second president of the United States, division pervaded the land and a debate raged in both the public and private space: Shall we have liberty or order? Could a people expect a measure of both?

Adams, though an early patriot leader and the nation’s first vice president, had neither the notoriety nor the unifying potential of a George Washington. And he knew it. Ill-tempered, insecure and highly sensitive, Adams appeared unsuited for the difficult task at hand. The body politic was fracturing into opposing factions—his own Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans—while the country itself was swept to the brink of war, first with Britain and then with revolutionary France.

Looking back, the ending seems preordained: Of course the republic could never have failed, we are prone to believe. Only this was far from a certainty, and the outcome was a near-run thing. America nearly came apart in the crisis of 1798-99.

Divided at the Onset: Republicans, Federalists and Conspiracies Against Liberty

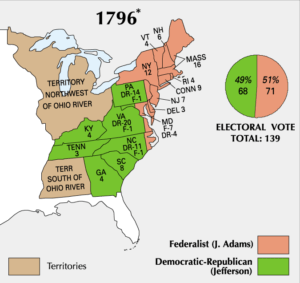

Even a quick glance at the electoral map from 1796 demonstrates not only how close was the contest, but how divided were the various regions. Indeed, even in this first truly contested election (Washington’s two terms seemed predestined) one notes an emerging sectional division between a Federalist North and a Republican South. Remember that this was an era in which most Northern states had begun to phase out slavery, whereas the South developed an increasingly slave-dependent society. The Federalists dominated in the North, especially along the coast. John Adams was a Massachusetts man, Jefferson a Virginia planter. The division is striking—as though the next century’s Civil War was fated from the start. It wasn’t, of course; nothing truly is, but no doubt the seeds were there at the onset.

The North, in addition to having a smaller enslaved population, was highly commercial and increasingly urbanized. The South remained an agrarian slave society. Still, slavery was not the main division in the second half of the 1790s. Liberty itself was the defining concern—liberty’s exact contours and the limits of dissent.

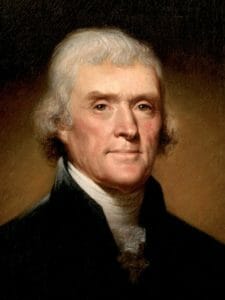

Not that the election of 1796 bore much resemblance to our modern contests. Both candidates stayed home, neither actively campaigned and each left it to friends, allies and sympathetic newspapermen to make their respective cases. Nonetheless, Adams and Jefferson—once and future friends—epitomized exceedingly divergent governing philosophies.

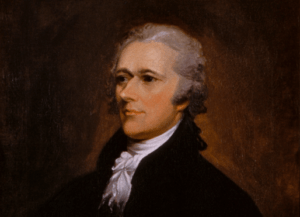

Adams lacked the vigor and extremist positions of some Federalists (notably Alexander Hamilton) but believed fervently in the need for a strong, central government to calm and control the tempers of the states and the public alike. Once an ambassador in London, he tended to favor the British in their ongoing worldwide war with France.

Jefferson, conversely, distrusted centralized power and never overcame his youthful revolutionary hatred for all things British. It was Jefferson, recall, who remarked during Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts that “a little rebellion” now and again was “a good thing.” He had been ambassador to Paris and remained faithful in his support of revolutionary France.

So divided were the American people over this ongoing, destructive war in Europe that ardent Republicans took to wearing liberty caps—stocking-like headgear favored by French republicans—and French-style tricolor cockades on their hats. Federalists, usually sympathetic to the former mother country, responded in kind by adopting a black cockade with a white button to differentiate themselves from the Francophile Republicans. Attire as much as ideology, it seemed, divided Americans into two camps.

And, in a system that may seem farcical to modern readers, Jefferson—who was narrowly defeated—would therefore become Adams’ vice president. Imagine Hilary Clinton (“Lock her up!”) serving beside President Trump. The expectation in the day was that country would—for good gentlemen, at least—precede party loyalties. That assumption was wrong more often than not. Indeed, until the later adoption of the 12th Amendment, the Constitution stipulated that the second highest vote-getter would serve as vice president.

The political culture, too, was absurdly different from our own day. Personal honor was a deadly serious matter, and dueling (sometimes, though rarely, to the death) constituted an elaborate political ritual to protect reputations. Fistfights broke out on the floor of Congress. It all made sense in an odd way. In the tumultuous 1790s, neither side saw the opposition as possessing a credible dissent. Rather, the fight appeared existential—with the other side representing a threat to liberty or order itself! Federalists used the once pejorative (but gradually more acceptable) term “democrat” to describe their unseemly, anarchic Republican foes. To Jefferson’s Republicans, Adams and his ilk were not “federal” in any sense of the word; rather, they were monarchists, aristocrats even, and the enemies of liberty!

Such was the volatile setting when outright war with France nearly broke out.

The First War on Terror: Immigration, Sedition and the ‘Quasi-War’

“The time is now come when it will be proper to declare that nothing but birth shall entitle a man to citizenship in this country.” —Federalist Congressman Robert Goodloe Harper

“[The Alien Act] is a most detestable thing … worthy of the 8th or 9th century … dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States.” —Vice President Thomas Jefferson (1798)

Imagine a nation at “war” with a revolutionary ideology. Not a full-fledged, declared war, but a seemingly endless conflict against an amorphous entity thought to imperil the very fiber of the republic. Fear abounds—fear of foreigners, of subversives within. Elected leaders begin to restrict immigration, to deport aliens and to police the untrustworthy media. Nothing short of avid patriotism is acceptable in the midst of the ongoing crisis. Americans are at each other’s throats.

The time I’m describing has long since passed, two centuries in the rearview mirror, long before anyone heard the name Donald Trump. Still, the comparison—and the alarmism of our present—is instructive.

In 1798, revolutionary France—to which Americans arguably owed their independence—and the United States were brought to the verge of war. The French seized U.S. ships en route on the high seas to trade with Britain, still a top commercial partner for American merchants. When President Adams sent envoys to discuss the matter, they were belittled and dictated to by three French agents. The agents were later described by the envoys as Mr. X, Y and Z, and each had demanded humiliating apologies and bribes as a precondition to even begin negotiations. Adams recalled his envoys, and the American people seethed with anger. The bribery demand was particularly galling, and one American envoy, according to a later newspaper account, declared that the U.S. would spend “millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!”

The Federalists felt vindicated. Indeed, the party would win elections up and down the Atlantic Coast in this period. Alarmist factions within the Federalist ranks began to question the very patriotism and loyalty of the “fifth column” of Republicans. Riots broke out in Philadelphia between pro-French and pro-British factions, and Republican newspaper editors were attacked. Conspiracy theories and exaggeration of threats abounded. As tensions rose, President Adams called for a day of prayer and fasting as a show of national unity. One particularly onerous rumor spread during the fast: Republican insurgents, so said the scare-mongers, planned to burn the U.S. capital.

As the war drums beat, Adams asked Congress to sanction a Quasi-War with France, what Adams called “the half war,” and indeed the resolution passed. Merchant ships were armed and the military budget soared, though hysteria spread faster than actual combat at sea. Hard-line Federalists feared civil war and seemed to spy treasonous French agents around every corner. Nativism and fear pervaded the land. It is likely to be so during a war scare.

What followed was a veritable constitutional crisis—perhaps this nation’s first. Fear of foreign French intriguers, and their Irish allies, expanded like wildfire. In response, Congress first passed the Naturalization Act, which extended the wait before applying for citizenship from five to 14 years. Then, the Alien “Friends Act” gave the president the extraordinary power to expel, without due process, any alien he judged “dangerous to peace and safety.” It must be said that no aliens were actually expelled by Adams, but the accumulation of so much discretion and power in the executive branch terrified Republicans.

Even more worrisome were the subsequent attacks on the “disloyal” press—meaning Republican or non-Federalist newspapers. This was a remarkable power to grant the federal government, seeing as newspapers were the central medium of communication and the glue that held together partisan factions of the day. The actual text of the Sedition Act, read today, is chilling. The legislation declared it a crime to:

Write, print, utter or publish … any false, scandalous, and malicious writings against the Government of the United States, or either House of the Congress of the United States, with the intent to defame the said government, or either House of Congress, or the President, or to bring them … into contempt or disrepute, or to excite against them … the hatred of the good people of the United States.

How could it be, the modern reader might ask, that an elected body could so restrict the beloved freedom of the press less than two decades after a revolution was waged in defiance of tyranny? And, indeed, the vote on the matter was highly contested and narrow: 44-41 in the House of Representatives.

Vice President Jefferson, a fierce opponent of the bill, no doubt took notice that the defamation of the vice president was conspicuously absent from the text of the Sedition Act. He saw the bill for what it was: a thinly veiled “suppression of the Whig [Republican] presses.” What, after all, many Republicans asked, had we just fought a war for, if not for freedom of speech and of the press?

This time, unlike in the Alien Act, the legislation was quickly put to use by Federalist courts. Twenty-five people were arrested, 17 indicted and 10 convicted (some jailed). Most were neither spies nor traitors, but rather Republican-sympathizing newspapermen. The government even arrested Benjamin Franklin Bache (grandson of the esteemed Founder), who died of yellow fever before his trial. The Sedition Act expired at the end of Adams’ administration, but its specifics were not declared unconstitutional until a case was brought forward by The New York Times in the 1960s!

This was politics, not national security, and the Republicans knew it. Some of those jailed styled themselves martyrs of liberty. One, Matthew Lyons, successfully ran for Congress from within his prison cell. Partisan loyalties had divided an administration and brought the nation to verge of civil war.

Seeds of Secession: Jefferson, Madison and the Virginia/Kentucky Resolutions

“A little patience, and we shall see the reign of witches pass over, their spells dissolve, and the people, recovering their true sight, restore the government to its true principles.” —Vice President Thomas Jefferson referring to the Sedition Act in a letter to John Taylor (1798)

The beleaguered Republicans would not go down without a fight. Despite the suppression of the press, the actual number of Republican-leaning newspapers exploded. And, though the resurgent Federalists controlled the Congress in Philadelphia, prominent Republicans turned to the state legislatures to oppose the Alien and Sedition Acts. As the tensions rose, so did the rhetoric. Many opponents of the bills took to referring to the federal government as a “foreign jurisdiction.” This is not dissimilar to the language employed today by some libertarian ranchers in the American West and some militiamen.

Jefferson himself believed that the federal government—of which he was vice president!—had become “more arbitrary, and [had] swallowed more of the public liberty than even that of England.” James Madison, an old and true Jefferson ally, left retirement and entered the Virginia Legislature. Now, Jefferson the disgruntled vice president and Madison the lowly state representative set to work making the case for the unconstitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

They did not, interestingly, turn to the federal courts. These they saw as Federalist-dominated, and besides, the modern conception of judicial review was not yet established. Instead, in a far more devious, though potentially problematic way, Madison and Jefferson drafted state “resolutions” for Kentucky and Virginia, which made the extraordinary claim that state governments could rightfully declare federal legislation they deemed unconstitutional to be “void and of no force.” Essentially, states could nullify federal law because, as the asserted, the Constitution was but a “compact” between the many states.

Kentucky and Virginia urged the other states to pass similar resolutions, though none saw fit to do so. Still, this was a remarkable moment that set a dangerous precedent. Imagine Vice President Pence secretly drafting an Indiana resolution that declared a prominent piece of President Trump’s agenda to be null and void! Furthermore, unfortunately, Jefferson’s and Madison’s attempts to protect civil liberties blazed a perilous path. The concept of nullification and, finally, of Southern secession would spring from the same lines of argument the two esteemed Founders set forth in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. Civil war, of course, was the unforeseen result.

Good Men, Bad Politicians: John Adams and the Peace That Ended a Presidency

“Armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few.” —James Madison (1795)

In addition to legislation meant to ensure “order,” Adams and the Federalists actively prepared the nation for war. Adams, for one, was doubtful that France could or would ever invade, but he preferred that the nation be prepared. Other ultra-Feds, like Hamilton, saw opportunities for the power and expansion of the federal government during the war scare.

More naval funding was authorized in one year than in all previous congresses to date. And, ultimately, a country that had once vehemently opposed standing armies now raised a “New Army,” 12,000 men strong. Pushing for this rapid expansion was Alexander Hamilton, who more than any other Founder desired a European-style fiscal-military state. In fact, Hamilton wanted to lead said army, though he settled for second-in-command to the largely ceremonial leadership of George Washington (again called out of retirement).

War hysteria quickly got out of hand. Republicans feared, not without some merit, that the true purpose of this “New Army” was to suppress the political opposition. Indeed, most of the officers appointed to the new force were of Federalist leaning. But Hamilton had even more grandiose notions than domestic oppression. He saw opportunities aplenty in the case of a war he seems to have truly desired. War with France, he argued, would allow the seizure of Louisiana, Florida and maybe even distant Venezuela from France and Spain!

President Adams, though, had far more common sense, and retained enough of the revolutionary “spirit of ’76,” to deny Hamilton the supreme command and the empire that the man so desired. “Never in my life,” Adams later recalled, “did I hear a man [Hamilton] talk more like a fool.” In a letter to a colleague, Adams went so far as to declare Hamilton “the greatest intriguant in the World—a man devoid of every moral principle—a Bastard.”

George Washington, too, quickly lost interest in the military expansion and soon returned to Mount Vernon, and eventually tensions and the war scare eased. But the main catalyst for peace was President Adams himself. Adams retained some of his fear of standing armies, loathed Hamilton and knew war was the last thing the new nation needed.

Thus, without consulting his Cabinet and in opposition to his own party agenda, Adams sent a peace mission to France. This action cooled the Quasi-War and averted a civil crisis. It was not, however, a prudent political move. The actions of Adams inadvertently divided his once ascendant Federalist Party just before the election of 1800—when he would again face off against his vice president, Jefferson.

A (flawed) patriot more than a politician, Adams dismissed the Hamiltonians in his Cabinet and secured the Treaty of Mortefontaine, bringing to an end the Quasi-War with France. Unfortunately for Adams the paltry politician, word of this diplomatic coup did not reach American shores until he had been defeated in the 1800 balloting.

Liberty or Order: The Eternal Debate

“The Federalists of the 1790s stood in the way of popular democracy as it was emerging in the United States, and thus they became heretics opposed to the developing democratic faith.” —Historian Gordon Wood (2009)

It never ends, the debate. Even now, it is as though Adams and Jefferson were still alive, battling for the possession of our American souls. The relevant issues from the 1790s are as plentiful as they are astounding. So many of the questions of yesteryear are precisely those that Americans grapple with in 2018.

How free should the press be? What constitutes libel? How should government treat leakers (think Snowden or Manning) and whistleblowers? And what of immigration? Are foreigners a threat to the body politic? Do we need a “big, beautiful” wall? Should some migrants (i.e. Swedes) be more welcome than others (Arabs or Muslims)?

The Patriot Act, warrantless surveillance, torture, race, ethnicity, the bounds of protest (see the NFL-kneeling dispute), the “crooked” media, drones, Guantanamo, the scope of federal and executive power. It’s all there, isn’t it? Adams and Jefferson, if suddenly brought back to life in today’s United States, would not be able to fathom an iPhone but would no doubt be ready to weigh in on debates regarding searches and seizures of those devices. On one level we’ve come so far, on another … not so much.

The common denominator in all of this seems to be war—war or the fear provoked by war and the threat of it. It matters not whether the U.S. wages a Quasi-War with France on the high seas or fights a shapeless enemy like “terror” across the Greater Middle East. The questions remain, the passions flare. We divide into camps, armed—sometimes literally—and oriented on our domestic enemies. Today’s “liberals” are not seen as misguided although valued countrymen but as traitorous weaklings ready to sell out America. “Conservatives” aren’t folks standing for time-tested values but instead are fascist authoritarians bent on tyranny.

It all seems so far off the rails. And it is dangerous.

Through modern eyes, we are apt to see this division as a unique and exceptional feature of contemporary politics. But, oh no, it was always thus.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 9: “The Early Republic, 1789-1824” (2011).

Gordon Wood, “The Significance of the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 8, No. 1 (Spring 1988).

Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815” (2009).

* * *

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.