American History for Truthdiggers: Lies We Tell Ourselves About the Old West

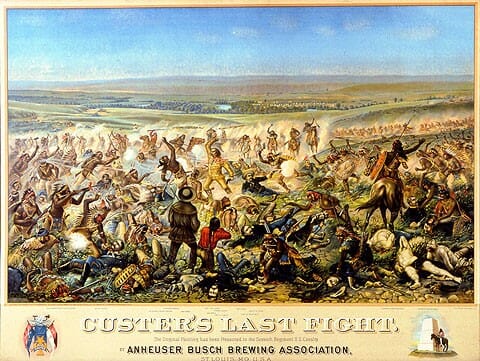

For Native Americans, the white man's tale of noble settlement of an empty frontier in the second half of the 19th century masked a genocide. “Custer’s Last Fight," a lithograph based on an 1884 painting by Cassilly Adams and published by the Anheuser-Busch company in 1896. The image hung in thousands of taverns across the United States.

“Custer’s Last Fight," a lithograph based on an 1884 painting by Cassilly Adams and published by the Anheuser-Busch company in 1896. The image hung in thousands of taverns across the United States.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 19th installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 19 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18.

* * *

“They [the Sioux Indians] are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts and by no means as people.” —Gen. John Pope, in instructions to his officers during an Indian war in Minnesota (1862)

The West. The frontier. Few terms, or images, are as quintessentially Americans or as culturally loaded as these. Interestingly, the West—unlike other regions—is often defined as both a time and a place. It is also hopelessly shrouded in myth. Americans leaders, from George Washington to Donald Trump, frequently claimed that the West, the frontier, somehow defined us as Americans. It was long seen as a place of opportunity, rebirth even. If a man failed in the East, well, then, “Go West, young man,” as one Indiana newspaper declared in the popular phrase it coined.

The truth, of course, is messy. Even focusing, as we will here, primarily on the West’s most immortalized era (1862-1890), the serious historian finds a story teeming with less fact than fiction. Some have even questioned whether there is any merit in studying the West as a separate historical discipline. Still, in a series such as this, something must be said of the place and the time. Americans, after all, seem to have decided that the frontier does, in fact, define us; that the West is who we are. And so it is, for better or for worse.

Furthermore, there are many other compelling reasons to study the West, even if they do not comport with our “cowboys and Indians” cinematic image from mid-20th century movies (when the Western genre dominated the film scene). Firstly, the American West was an important “meeting ground,” where Anglo, black, native, Hispanic and Asian-Americans coalesced. Though land and wealth were the main goals of these competing factions, defining the West also became a contest for cultural dominance. The West was a place where the federal government (then much more circumscribed than now) first expanded its role and played a key part as financier, organizer, referee and lawman. Additionally, the West demonstrated the radical nature, and boom-bust cycle, of American capitalism in the starkest of ways. Finally, of course, the West of the late 19th century was the time and place where one version of Native American sovereignty ended and a new phase began. This, truth be told, was one of the great—yet complicated—crimes of the American experiment.

Myth Versus Truth: Reinterpreting the ‘West’

Americans have long mythologized the West. From Plymouth Rock, to Manifest Destiny, to the Plains Indian wars, to John Wayne on the 20th-century silver screen, it all looks the same in the American imagination. Cowboys and Indians, lawmen and villains, soldiers and savages, farmers and miners, and always, ultimately, black hats and white hats. It’s remembered for its excitement and mystique, yes, but also as a morality tale—good guys and bad guys. As always, of course, the reality is far more complex, more nuanced, more gray.

Still, it’s valuable to parse out truth from legend, fact from fiction. After all, the real West—to the extent that it can ever be defined—is so much more interesting, fascinating and wholly human. Let us, then, ever so briefly, address but a few of the defining symbols and myths of America’s shared Western past.

Gold rushes. From California to Nevada, from Montana to the Black Hills of South Dakota, the craze for precious metals became a fixture of the Western saga. The San Francisco 49ers of the National Football League bear the nickname of those who came in the first major wave of the California Gold Rush, in 1849. In the common image, any lone man could make his fortune simply by panning for gold and catching some luck. It all fits comfortably within the altogether American obsession with the so-called self-made man.

The reality was uglier and less satisfying. Mining was an important factor in the West. Miners flooded remote areas faster than farmers. Their presence could cause trouble—as when miners set up settlements in places white people had never before inhabited, often provoking Indian wars. Most importantly, the essence of mining captured the extractive nature of Western culture. In the end, though, only a tiny percentage of miners struck it rich. Mining turned out to be complicated and increasingly technological. The individual panner of gold often arrived too late, after the surface gold had been captured, and found that his mining method was outmoded and inefficient. Soon enough, the power shifted to corporations, and most miners worked for a lowly wage in dangerous, dismal conditions.

By the late 19th century, many mine owners were Easterners who had never set foot in the West. They simply added investments in mining to their complex financial portfolios. Miners weren’t strictly rugged individualists, either. Indeed, few American industries lent themselves so easily to a Marxist analysis of class struggle. Miners unionized, led strikes and sit-downs and battled (often fatally) with federal troops or National Guardsmen. Seen in this light, the Western miner’s condition bears striking similarity to that of Eastern factory workers.

There were legitimate socialists and revolutionaries among the miners. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or “Wobblies,” had a strong presence in the mine shafts. The reaction of conservative mine owners and bought-off lawmen was often vicious. In Bisbee, Ariz., hired vigilantes supported by a local sheriff rounded up 1,186 striking copper miners and supporters, forced them onto rail cars and shipped them over the border to New Mexico. Two were beaten to death.

Overall, the horrid social condition of miners couldn’t have been more different from the Jeffersonian Western ideal of the small, independent farmer setting roots in the soil. Thomas Jefferson, in fact, would have been horrified by the sight of these dirty wage slaves toiling their days away and engaging in debauchery at temporary mining camps at night, totally untethered to place or agriculture. Furthermore, a good number of the miners weren’t Jefferson’s idealized white men at all: They were Irish Catholics or, worse still, Chinese immigrants. Still, in other ways, mining was a defining Western experience, involving all the key factors of real Western life: class, race, chance and federal largesse.

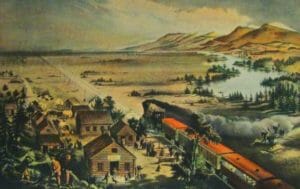

Railroads. The “iron horse” steam engine traversing the plains is one of the iconic images of the West. The railroads embodied civilization as much as raw technological advance. Yet contrary to their clean, straight, parallel lines on maps, the railroads were a complicated, inefficient industry. First of all, although Chinese or Irish workers were seldom in the iconic (staged) photographs depicting the meeting of intercontinental lines, they constituted the vast majority of railroad workers. Many thousands died constructing the rail lines that connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

The corporations that built the railroads were more interested in profit than quality craftsmanship and often had to double back to improve dangerously feeble tracks. The railroad entrepreneurs usually weren’t up-by-the-boot-straps individualists either. Rather, the railroaders were extraordinary recipients of federal largesse—what we might call corporate welfare. The federal government subsidized the construction of the transcontinental lines with cash and enormous land grant subsidies. In many cases, a railroad received 200 square miles of adjacent land for each mile of track completed. Thus, despite the supposed “free land” granted to willing pioneers by the 1862 Homestead Act, it was actually the railroad companies that owned much of the best (and most valuable, due to its proximity to transportation) land in the West. Where possible, the corporations engaged in speculation and sold the land at a handsome profit.

Railroaders were often highly corrupt, plaguing and embarrassing the Grant administration (1869-1877) in scandal after scandal. They bribed politicians, set up subsidiaries that robbed the taxpayer and hired vigilantes to intimidate striking workers or nearby Indians. The railroads, as beneficiaries of generous federal welfare, weren’t always in tune with supply and demand. Lines sometimes were overextended and had to be abandoned in part because they proved unnecessary and unprofitable. Companies sometimes ran lines into arid areas (like western Kansas) that were hard to settle. Railroad supply, by the late 19th century, had far outstripped citizen demand, but the federal dollars kept rolling in. As the historian Richard White wrote, eventually “empty railroad trains ran across deserted prairies to vacant towns.” However, one thing the railroads did do was affect the future layout and prosperity of townships and cities. Existing settlements unlucky enough to lay distant from a rail line or station eventually withered away, and as a result so-called ghost towns dotted the West. Conversely, a simple bribe from a local politician might motivate railroaders to place a previously unplanned stop in a town. Indeed, the railroads—as much as the later federal highways—defined the geography of the Western landscape.

Rugged Self-Sufficiency. One of the more persistent myths holds that Westerners were all hardy individualists, opposed to federal intrusion and beholden to no one. Though still pervasive, such a description strikes the serious historian as farcical. From start to finish, Western territories, states and citizens were among the largest recipients of federal aid. Indeed, when not accusing the federal government of some slight or infraction, Westerners were constantly clamoring for more federal aid. It was in the West, in fact, where the federal government first meaningfully inserted itself into Americans’ daily lives. A Western region was organized into a territory—under the direct control of a federal governor—before it was, eventually, accepted as a new state. This could happen almost immediately, as in the case of California, or take 64 years for states like Arizona and New Mexico.

Still, regardless of when their regions reached statehood status, Westerners were reliant on the federal government. They desired, and expected, loans and aid for enterprise and transportation, soldiers for protection (and conquest of Indians), and surveyors to organize and distribute (cheaply!) the land. Politically, though the Western states complained (then as now) of powerlessness, the reality couldn’t have been more divergent. Blessed with massive lands, precious natural resources and comparatively few people, Western states still had two senators and at least one congressional representative in the House. Indeed, a state like Wyoming—which still has roughly the population of New York City’s least populated borough, Staten Island—has the same number of senatorial representatives as the 30-times-larger state of New York (in terms of residents). Then and now, the West was actually proportionally overrepresented in Washington.

Well into the 20th century, the West received federal assistance disproportionate to its population. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 provided for generous leasing of federal land to Western ranchers, and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal created many federal work projects in the Western states. In fact, during the New Deal, Wyoming received, on a per capita basis, three times the average amount of direct federal financial assistance given to states. So much for rugged independence.

Independent Family Farmers. The vision of the independent, small family farmer was the ultimate Jeffersonian ideal of future Western American prosperity. And, though millions of small farmers would settle the West, corporate agro-business or land speculation was just as often the agricultural norm. Real estate—more than gunfighting or Indian fighting—was the dominant force in the American West. With all that “open” land, settlement, squatting and speculation became the name of the game. Moreover, in the minds of many Americans, there was never enough land—though, interestingly, the West still hasn’t “filled up.” Americans of the day feared that the United States would run out of land and end up like Europe, crowded and riven by the class structures that develop in the absence of well-distributed land ownership.

Though just about all Western land was technically owned by the central government, few settlers were willing to wait on federal speculation, division and allotment. Many simply followed the notion “first in time, first in right” and squatted on available lands. (For the government, using the Army to remove them rarely seemed viable.) Wealthy speculators turned a pretty profit by buying large tracts of the cheap land from the federal government and then selling it to smallholders. From large-scale speculation and massive private landholdings it was but a short step to the 20th-century mechanized agro-business that has driven so many family farms into insolvency.

Nor did farm settlement always make sense. Much of the land west of the 98th meridian is semiarid, and rainfall in these areas (western Kansas and Nebraska and eastern Colorado, for example) was insufficient to support agriculture. By the early 20th century hundreds of thousands of these settlers failed and retreated eastward. This explains why many towns in western Kansas had a higher population in 1880 than in 1980. Only through analysis of this mix of failed irrigation, land squatting and high-finance speculation can one begin to understand the byzantine and poorly planned nature of Western settlement. Seen in this light, it becomes understandable that many native tribes struggled to understand white notions of “property.” It hardly made sense to Anglo Americans; why should it seem natural for a pre-Columbian civilization?

Ranchers and Cowboys. There is no more romantic myth in the American West than that of the cowboy. Indeed, the image of the cowboy has come to define the place and time—so much so that men and women in the American South and West still wear the purported clothing styles of the cowboy. So, just who were these cowboys and where did they come from? Well, the first were Spaniards, and then Mexicans. It was the Spanish who brought the cattle that cowboys would drive to market in the New World. Indeed, the styles of the cowboys came from Hispanic clothing and culture. Consider the Spanish loanwords that entered the American lingo and mystique of the cowboy: lasso, rodeo, ranchero.

Still, the cowboy on horseback driving cattle from Texas to Kansas City (or some other railroad town) had a heyday of little more than two decades. The beef industry, like farming, was quickly mechanized, and by the end of the 19th century the era of the cattle drives was mostly over. Ranching became rather corporate, and the true conflict was usually not between cowboys and rustlers but between ranchers and nearby small farmers. It is important to remember that the cowboy of our imagination was not on the Western scene for long and that he didn’t always look or act the way we imagine. There were black cowboys, many Mexican cowboys (they had invented the business), and, new studies show, there was a fair amount of homosexuality practiced in these all-male communities. If it is thus, one wonders why, precisely, it is the image of the rugged, white American cowboy that has stuck in the collective national psyche. That it is so might tell us more about the American present than the past.

Gunfighters. The showdown in the dusty street at high noon between two men with six-guns—an outlaw and a sheriff—is one of the great melodramas of the West, especially as depicted in film. The clock strikes noon, each man quickly draws his weapon, and the fastest gun wins! Exhilarating. But, sadly, inaccurate. Cattle-town newspapers and other primary sources make no mention of such duels in the streets. Violence was rampant in the West, of course. Indeed, the murder rate in Dodge City, Kan., was about 10 times that of today’s New York City, and the less well-known mining town of Bodie, Calif., had a rate some 22 times the NYC rate. Still, less than one-third of the victims died in actual exchanges of gunfire. More than half were unarmed, often shot in the back and at a close distance. This was murder, not the martial chivalry of the imagination.

Another interesting point is that many of the romantic outlaws we remember today—such as Jesse and Frank James and John Wesley Hardin—were far less Robin Hood and far more racist than most modern Americans know. Many of these men were unreformed Confederates, angry at the government and ready to do violence to blacks. The James brothers had ridden with Confederate guerrilla leader William Quantrill and his raiders during the Civil War and were probably involved in Quantrill’s attack on Lawrence, Kan., in 1863, in which more than 150 residents were killed. Hardin, perhaps the most prolific killer of the era, thought of himself as a victim—a victim of “bullying negroes, Yankee soldiers, carpetbaggers, and bureau agents” in his native Texas. Most of these fabled outlaws were coldblooded killers and unreconstructed Southern bigots.

The End of Native Sovereignty: Four Phases of an American Tragedy

“It is very hard to plant the corn outside the stockade when the Indians are still around. We have to get the Indians farther away in many provinces to make good progress.” —U.S. Army Gen. Maxwell Taylor, comparing Vietnamese to American Indians in 1965

“Indian Country.” The term has become a military shorthand for any “wild,” “unconquered” region the U.S. Army attempts to “secure.” The Army and the native peoples of America maintain a strange relationship and kinship to this day. Think of it as the ultimate love/hate relationship. Indian fighting, after all, is what the U.S. military mostly did in the periods between the nation’s few major wars in its first century or so. At present, all helicopters in the U.S. Army inventory—Iroquois, Apache, Blackhawk, Chinook—bear the names of tribes or leaders the U.S. government once fought and conquered. This author served in modern-day “cavalry” (reconnaissance) units, where each Friday formation meant donning vintage Stetson hats and riding spurs. Each cavalry unit’s flag, or guidon, sports dozens of streamers commemorating battles fought long ago with Native American tribes and bands.

The relationship between the modern U.S. Army and its former Indian foes actually mirrors the complexity of the late 19th-century clash of these two forces. The Army was often brutal and bloodthirsty. So, too, were many Indians, though they lacked the capacity to exterminate large numbers of whites in the same way. Then again, the real danger to the Native Americans usually came not from soldiers but from white civilian settlers and vigilantes—and in these cases the Army was sometimes used to protect (however imperfectly) the Indians from pioneer encroachment. One way to frame the era from 1862 to 1890 is as a broad counterinsurgency waged by the Army across a large expanse filled with myriad actors and pursuing the ever-changing, often muddled policies of the U.S. government.

The real problem for the Indians was this: The U.S. never formulated a permanent Indian policy that would guarantee native sovereignty, and never had either the will or capacity to separate the settlers and natives. Unsurprisingly, given the choice between protecting natives and appeasing settlers, the government erred on the side of the white man. In broad strokes, U.S. government policy toward the Indians of the Great Plains and Far West went through four phases in the 19th century: removal from lands east of the Mississippi; concentration in a vast “Indian territory” between Oklahoma and North Dakota; confinement to much smaller “reservations” on part of that land; and assimilation of the Indians into white American-style farming and culture, through the allotment of even smaller, individual tracts of barren land. The natives lost at every step, and their territory shrunk with each new phase. Still, the Indians remained active agents during this period, winning victories, suffering defeats, fighting each other, and, often, allying with the U.S. Army. It was a complicated, tragic battle for the Native Americans of the American West.

Removal. This was the policy of President Andrew Jackson. In 1830, he pushed through the Indian Removal Bill, which forced the five so-called “civilized” tribes to vacate their lands and move west of the Mississippi, and promptly ignored the Supreme Court when it objected on constitutional grounds. He and his successor, Martin Van Buren, went so far as to use the Army to evict the tribes at bayonet point and march them—in the infamous “Trail of Tears”—into modern-day Oklahoma. Thousands of Indians died, but the majority of white Southerners (who took over the land) cheered the presidents’ decisions. This was supposed to be a permanent Indian territory, a vast expanse into which the Native Americans would now be concentrated—and sovereign—in perpetuity. It was, of course, not to be. In an early sign of what was to come, when the five “civilized” tribes made the mistake of allying with the Confederates—from whom they expected more freedom and independence—the U.S. government made them pay: It subsequently confiscated half their lands. Indian territory would shrink and shrink as the years passed.

Concentration. During the period of concentration (roughly 1848-1873), the Indian wars never actually ceased. Miners, settlers and sometimes the Army violated supposed native sovereignty and moved onto the land. Furthermore, some tribes and bands refused to accept the white man’s overland trails and railroads running through their regions and attacked men and women on the roads. So the wars continued, brutally, even if the fiction of the vast Indian territory technically continued.

In 1862, a Sioux uprising in Minnesota, precipitated by crop failure and game reduction, resulted in the deaths of some 500 settlers. President Abraham Lincoln ordered the rebellion put down. The militia and Army suppressed the Sioux, captured hundreds, executed 38 and moved the rest to Dakota territory (into Indian country). In 1864, Col. John Chivington attacked a village at Sand Creek, Colo., during a war with the Cheyenne tribe. The massacre of some 200 Indians (75 percent of them women and children) should have come as no surprise, since Chivington had announced his intentions beforehand: “I have come to kill Indians and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians.” It is notable that Chivington’s men were local volunteers, not regular Army soldiers, and carried the hatred for Indians common to local settlers. The Sand Creek massacre only further inflamed the Plains in war, a state that was almost perpetual until 1878.

The most horrific and genocidal Indian experience came in California, which, because of the Gold Rush, never truly implemented a concentration or confinement policy. The whites wanted all of these rich Pacific lands. Here the 150,000 natives of California were pushed through a truncated version of all four phases in a span of only 12 years. The federal commissioners attempting to broker a treaty in 1851 made clear their expectations: “You have but one choice, kill, murder, exterminate, or domesticate and improve them.” Miners, ranchers and militia murdered thousands, and many more perished from diseases brought by the Gold Rushers. By 1860, only 30,000 California Indians (out of 150,000) remained alive—a record of extermination unparalleled in our troubled history with Native Americans—though, interestingly, few Americans remember this campaign today.

Many in the U.S. Army, too, were full of contempt for the natives. The senior commander in the West, Gen. Phillip Sheridan (of Civil War fame), declared in 1868, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” The Sioux tribes under Chief Red Cloud had given the Army a run for its money from 1866 to 1868, defeating just about every force sent against them in the Dakota territory and Montana. Eventually, the U.S. government agreed to destroy its regional forts and signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, which promised the Black Hills of South Dakota and other sacred lands to the Sioux and Cheyennes in perpetuity. Fort Laramie was one of the last treaties signed by the U.S. government with a sovereign Great Plains tribe. That time was passing. The end of war in 1868, in retrospect, was but a truce, during which the settlers and U.S. Army paused briefly but did not give up their hunger for Indian land on the Plains. The great chief Sitting Bull of the Sioux learned that lesson early and proclaimed that “possession is a disease with them [white men].”

The notion that the United States—or more accurately its settlers and prospectors—would actually yield the land between Oklahoma and North Dakota to a so-called concentration of Indians was, in hindsight, baseless. The government always wanted to own all the land between prosperous California and the Missouri River limit of settlement. Besides, land-hungry settlers and speculators had no intention of following federal Indian policy anyway. They knew the Army had too few soldiers to police the entire frontier, and that it would be relatively easy to cross the Missouri, find a plot in Indian territory and squat on the land. Would the federal Army have the will or capacity to protect Indians from the settlers? It was never likely.

Sen. Stephen Douglas of Illinois, a fierce advocate of a transcontinental railroad through Indian land, captured the common feeling and dispelled any lingering idea of a permanent Indian land. He noted, years before the Civil War, that “the idea of arresting our progress in that direction [West] has become so ludicrous that we are amazed. … How are we to develop, cherish and protect our immense interests and possessions on the Pacific, with a vast wilderness 1,500 miles in breadth, filled with hostile savages, and cutting off direct communication. The Indian barrier must be removed.” There was, rumor had it, gold and other precious minerals—in addition to millions of acres of fertile land—in that 1,500-mile breadth of Indian territory. Neither settlers nor federal officials were willing to follow the concentration policy and let the Indians be: “Progress,” as always, seemed to demand expansion. Some other method of Indian control would have to be found.

Confinement. The answer, many federal officials eventually decided, must be to confine the natives to shrunken parcels of land, known forever as Indian reservations. This strategy was in direct contradiction and contravention of earlier legal treaties signed with various native tribes and, along with the westward wave of settlers after the Civil War, made Indian war almost inevitable. There was always a fine line between concentration and confinement—both constricted the Indians to certain lands, but the reservations were generally smaller and far less rich in minerals and arable land. Various actors, and branches of government, led the transition from concentration to confinement on the “rez.”

In 1870, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress had the power to “supersede or even annul treaties” with Indian tribes. This ruling essentially destroyed the previous system of Indian affairs and emboldened settlers. Soon afterward, Congress followed the court’s decision, making any future treaty-making with the Indians illegal. The tribes were not, the text of legislation read, “to be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power.” Next came the ubiquitous settlers. After the “boy general” hero of the Civil War, George Armstrong Custer, led his 7th Cavalry on a “reconnaissance” expedition into the sacred Black Hills, he almost assured a new gold rush by publicizing the news that “from the grass roots down it was ‘pay dirt.’ ” Within two years, 10,000 miners were in the new town of Deadwood in the Black Hills. Unsurprisingly, miners were attacked by Sioux warriors who refused to countenance their presence.

The exhausted and scandal-ridden Grant administration decided to end the “Indian problem” once and for all. In what he declared his new “Peace Policy,” President Ulysses S. Grant ordered that all Great Plains tribes and bands no later than Jan. 1, 1876, move onto the truncated reservations outlined by his government or be considered “hostile.” Grant knew, of course, that this would mean a war. He probably expected one and had convinced himself that a final showdown was necessary.

Jan. 1 came and went, and nearly 10,000 Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho still roamed the Northern Plains. The Army moved in, and once again Custer was in the lead. Following his aggressive, often reckless (if courageous) instincts, Custer divided his force into three parts and converged on the huge combined native village near the Little Bighorn River in southeast Montana. He should have followed orders and waited for reinforcements. He didn’t. On June 25, 1876—just a week before the nation’s centennial celebration—thousands of warriors under Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull quickly overwhelmed and destroyed Custer and his wing of 250 or so troopers. The news of Custer’s “Last Stand” shocked the nation and entered the American mythology as a “gallant” defeat on par with the Greeks at Thermopylae or the Texans at the Alamo.

Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and other chiefs quickly split up. They knew that the defeat of Custer meant that the full force of the Army would now be unleashed upon them. They were right. Thousands of troops converged and waged a brutal “scorched earth” campaign during a brutally cold winter. Starving, outnumbered and exhausted, within a year most Indians withdrew to their reservations. Crazy Horse was the last to surrender and was subsequently bayonetted to death in an alleged escape attempt. Sitting Bull led his followers into Canada, where they were given some sanctuary, but within a few years they returned to their reservation because of food shortages. It turned out that Custer’s “Last Stand” was really the last stand of the sovereign Northern Plains tribes. That day’s victory by the Indians ultimately ushered in their final removal to reservations.

Assimilation and Allotment. The seeds of forced assimilation of Indians and conversion (into farmers) had long been planted in the Anglo mind. As early as 1859, an annual report of the Bureau of Indian Affairs noted, “It is indispensably necessary that [the Indians] be placed in positions where they can be controlled and finally compelled by sheer necessity to resort to agricultural labor or starve. … There is no alternative to providing for them in this manner, but to exterminate them.” Ironically, when the new policy of assimilation and allotment (of land plots to individual Indians) came to pass in the 1880s, it was ushered in by white Easterners who called themselves “Friends of the Indian.”

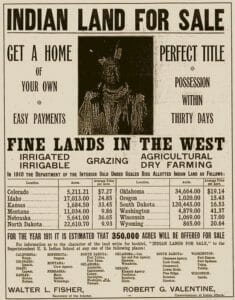

These men—and many women—believed that Indians must be converted from hunters who held land in common into white-style farmers and property owners. If they weren’t thus transformed, the “reformers” believed, the natives would become extinct. One reformer, Carl Schurz, wrote that “[civilizing them] which once [seemed] only a benevolent fancy, has now become an absolute necessity, if we mean to save them.” The signal achievement of the Assimilation and Allotment phase was the Dawes General Allotment Act (1887), which broke reservations into multiple tracts to be allotted to individual Indians, ostensibly for farming (which was often impossible due to the choice of barren, arid lands for reservations). The kicker was this: The millions of acres left over would then be open for sale to whites.

The Indians themselves, of course, were barely asked what they preferred. When they were, a majority of Indian tribes opposed the allotment policy. The resulting land cession was disastrous. In 1887, Indians held 138 million acres. Over the next 47 years, 60 million of those acres were declared “surplus” and sold to whites. Other lands were desperately sold off by Indians or ceded to the government for much needed cash. By 1934, the Indian tribes held only 47 million acres.

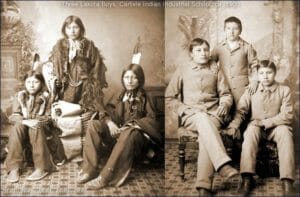

There was also a cultural component to the new phase of “Indian policy”: assimilation. Consider what followed to be “cultural imperialism.” Indian children were sent to distant Eastern boarding schools—most famously the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania—where they were taught in English alone, were told their parents’ ways were backward and were forced to wear American-style clothes and hairstyles. The women were dressed in Victorian dresses and taught piano, the boys drilled in uniform as military companies. The secretary of the interior summed up the policy: “If Indian children are to be civilized they must learn the language of civilization.” Clearly, he meant a more holistic transformation than the simple learning of English. Tribal life was upended.

The tragic last hurrah of Indian independence came in 1890. A Paiute holy man in Nevada preached a new sort of (nonviolent) religion. If Indians gave up alcohol, lived simply and traditionally and danced a certain slow dance, the Great Spirit would return them their lands and white ways and implements would disappear. By the time the belief reached the Northern Plains and the Sioux tribe, it had garnered a slightly more militant message and spread widely among the hopeless and despondent tribe. The “Ghost Dance” terrified whites and Indian agents, and when a band left the main reservation to dance on the Badlands of South Dakota, the U.S. Army sent in the ubiquitous 7th Cavalry Regiment (no doubt yearning for vengeance). Tribal police were sent to arrest Sitting Bull at his home, and in violence that followed, Sitting Bull and more than a dozen other men—both policemen and supporters of the chief—were killed.

The cavalrymen then set out in the winter snow and surrounded the Ghost Dance band along Wounded Knee Creek. The soldiers began disarming the Sioux when a gun went off. A massacre ensued, and the soldiers fired four new machine guns down into the encampment. One hundred forty-six Indians were killed, including 62 women and children. It was more massacre than battle. Twenty-five soldiers were killed, most of them probably shot in crossfire from their own forces. As a tragicomic if instructive coda, the U.S. Army—desperate to depict the incident as a “battle”—awarded no fewer than 20 Medals of Honor to the troopers at Wounded Knee. They have never been rescinded.

Looking back, what happened to the natives of America seems so inevitable. But was it? Could not the United States have settled for just a bit less expansion and allowed a permanent sovereign Indian Territory to develop along its own chosen lines? Couldn’t reservations have been placed on more fertile land? And, furthermore, could not those yet smaller reservations have stayed in Indian hands rather than been “allotted to whites”? Of course. There existed alternative options at every step of the way.

Ultimately, the U.S. government always lacked the will and capacity to protect Indian sovereignty. It’s an old story, really—something President Washington had predicted. In 1796, he wrote, “The Indians urge this [policing of a line between whites and natives]; The Law requires it; and it ought to be done; but I believe scarcely anything short of a Chinese Wall or a line of troops will restrain Land Jobbers and the encroachment of settlers.” The tale was basically the same from 1796 to 1890. The Army was rarely large enough to create that “line of troops,” and the government was never willing to meaningfully use the military resources that existed to evict white Americans.

Role Reversal: The Anglicization of the Southwest and California

Just who were the “immigrants” in the American Southwest and Pacific Coast? Today, there is an easy, if inaccurate, ready answer: the Mexicans. Yet in truth, a Hispanic and mestizo population and culture preceded Anglo-American conquest (1848) by some 250 years. Furthermore, Native American peoples had themselves been conquered by the Spanish in the late 16th century and antedated European rule by perhaps 10,000 years. What’s more, native peoples had fought each other for the land throughout the continent’s settled history. This wider view certainly complicates the traditional American political attitudes of our own day and raises as many questions as answers.

As should by now be clear, the West was never truly empty—no matter how often the artists of the period romantically depicted it as such. One of the strongest and most embedded communities was that of the Hispanic and mestizo descendants of the Spanish invasion. Spain permanently entered the American Southwest as early as 1598, with Juan de Oñate’s conquest of New Mexico from the Pueblo Indians. And yet, to watch a classic film, or to read an old Western dime novel, is to erase these Hispanic and mixed-race peoples from the story of the West. They were neither the cowboys nor Indians, soldiers nor native warriors, of the traditional tale. They don’t fit. That this should be the case is fascinating, if tragic. The people we now call Mexicans, Mexican-Americans or Hispanics were present and effusive through the entire “classic” era of the American West. Let us remember their story.

The original (Hispanic) residents of California and the Southwest were promised their private landholdings would be protected under the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, created at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War. It was not to be. Swindlers, settlers and hustlers tricked or bullied thousands of Hispanics off their land in the decades following the war. It wasn’t enough that the Yankees had conquered half of Mexico, the residents complained; now their lands were forfeit too. During the California Gold Rush, a Civil War veteran and forty-niner wrote in the Stockton Times that “Mexicans have no business in this country. The men were made to be shot at, and the women were made for our purposes. I’m a white man—I am! A Mexican is pretty near black. I hate all Mexicans.”

Yet, New Mexico, for example, remained majority Hispanic into the 20th century (which may help explain why it was not admitted as a state until 1912), but even there Hispanics held minimal political or economic power. In fact, they divided among themselves as many Hispanics sought to “Europeanize or ‘whiten’ themselves,” by claiming Spanish, rather than native, descent. This, some thought, would protect them from the worst of white infractions, though it didn’t always work. The victims of lynching, it turns out, were not limited to Southern blacks. Mexicans were often extrajudicially murdered for alleged crimes or just to “encourage them to stay in their place.”

Still, Mexicans weren’t erased from the Southwest. They were needed as agricultural laborers—then and now—just as blacks were in the Old South. Nativists (anti-immigration advocates) fought the local planters (who needed the labor), fearing that migrating Mexicans might “reverse the essential consequences” of the Mexican-American War. Racial lines hardened throughout the 20th century, and in 1930 the U.S. census form added a separate classification of Hispanics as “Mexican.” Before then Hispanics fell under the category of “white.”

Culturally, the Hispanics often found themselves erased by or amalgamated within an Anglo Texan or Californian society and mythology. In the process, northern Mexico became the Southwestern United States; cowboys became homogeneous and white, Indians became a savage red. There wasn’t much identity left for those in between.

Whether in the 19th century or today, the border between the U.S. and Mexico has been little more than a legal and social fiction. Like the Indians, the Hispanics of the Southwest had been conquered, but never truly erased. Texas and California were once northern Mexico. Which raises salient questions today: Are “undocumented” Mexican immigrants “illegal intruders,” or rightful residents of “Occupied America”?

* * *

Historians often described this period in Western history (1862-1890) as another type of Reconstruction—something similar to what was attempted in the post-Civil War South. There are indeed parallels: a military presence, violence, federal impotency, citizen apathy and racism. Still, the analogy falls short. It is problematic to compare Indians to recently freed slaves or to former Confederates. In the end, the U.S. government abandoned the freedmen and turned power back over to the Confederates within a dozen years. In the West, conversely, few attempts were made to “reconstruct” or restrain the land-hungry settlers, and the government actively backed (and abetted) the invaders. Furthermore, the Indians permanently lost their land—and for what crime? The Confederates had seceded, thereby committing treason, and received but 12 years of light punishment. Indians had adhered to treaties more faithfully than whites and were rewarded with banishment, theft, war and at times extermination.

The legacy, and tragedy, of the American West is with us still. As a classroom exercise on the heels of the 2010 census, I often ended my lesson on this topic at West Point with a slide listing five of the poorest U.S. counties. Then, I’d circle four—Buffalo, Todd and Shannon in South Dakota and Wade Hampton in Alaska—and ask the students what these counties had in common. They are all Indian reservations, of course, or places with major Native American majorities. Buffalo County holds the Crow Creek reservation; Todd, the Rosebud Sioux; Shannon, the Pine Ridge Sioux; and Wade Hampton a population that is 92 percent Eskimo. These counties, each filled with thousands of tragic individual stories, are living relics of our past; of each phase of the U.S. government’s calamitous Indian policy—first, removal, then concentration, followed by confinement to the reservation, and, finally, hopeless forced assimilation. Think on it: Within just a few hours’ drive of swanky downtown Denver, and just a few hours’ flight from hipster enclaves in New York City, there are veritable monuments of American crimes and human suffering: our semi-sovereign, mostly impoverished Indian reservations.

To visit one is to experience the past within the present. Disembark your plane in a crowded metropolitan center and take the long drive. You may cruise past federally owned ranch lands, through federally subsidized mega-farms, past long-abandoned mine shafts, through ghost towns that the railroads bypassed; stop for fuel where a man in a Stetson fuels his luxury pickup truck. Keep driving, past failed family farms that ran short of water on the arid plains, through strip mall after suburban strip mall; through a town with a vaguely Spanish name and past an oil rig. Finally, when the conveniences of modern life seem almost to have vanished, see the passing sign: “Entering [insert tribe] Reservation,” and proceed. You may feel as though you’ve left one world for another, but it is not so: All that you passed is the West—the legacy, the charm and the tragedy.

We are Americans: It is our complex inheritance.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher, “The American West: A New Interpretive History” (2000). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • Patricia Nelson Limerick, “The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West” (1987). • Richard White, “The Republic for Which it Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896” (2017).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.