American History for Truthdiggers: The Decade That Roared, and Wept

The Roaring ’20s ushered in a new modernity and energy but also held the seeds of a great and devastating economic depression. A new look for a new day: Models show off the "flapper" dress style in this circa-1925 photo.

A new look for a new day: Models show off the "flapper" dress style in this circa-1925 photo.

Editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the 23rd installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. The author of the series, Danny Sjursen, an active-duty major in the U.S. Army, served military tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and taught the nation’s checkered, often inspiring past when he was an assistant professor of history at West Point. His war experiences, his scholarship, his skill as a writer and his patriotism illuminate these Truthdig posts.

Part 23 of “American History for Truthdiggers.”

See: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10; Part 11; Part 12; Part 13; Part 14; Part 15; Part 16; Part 17; Part 18; Part 19; Part 20; Part 21; Part 22.

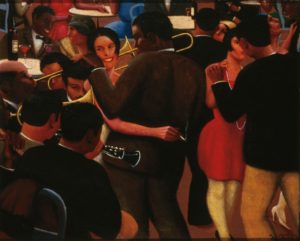

The Jazz Age. The Roaring ’20s. The Flapper Generation. The Harlem Renaissance. These are the terms most often used to describe America’s supposedly booming culture and economy during the 1920s. No doubt there is some truth in the depiction. Real wages did rise in this period, and the styles and independence of certain women and African-Americans did blossom in the 1920s—at least in urban centers. Still, the prevailing visions and assumptions of this era mask layers of reaction, racism and retrenchment just below the social surface. For if the 1920s was a time of jazz music, stylishly dressed “flappers” and lavishly wealthy Wall Street tycoons, it was also one infused with Protestant fundamentalism, fierce nativism, lynching and the rise of the “new” Ku Klux Klan. How, then, should historians and the lay public frame this time of contradictions? Perhaps as an age of culture wars—vicious battles for the soul of America waged between black and white, man and woman, believer and secularist, urbanites and rural folks.

The term “culture war” is familiar to most 21st century readers. Indeed, many are likely to remember the common use of the term to describe the politics of the 1990s, when politicians and common citizens alike argued about cultural issues such as abortion, gay marriage and prayer in schools. Those divided times have arguably continued into our present politics with a new fury. Something similar happened in the often mischaracterized 1920s. Few eras are truly one thing. Thus, the juxtaposition is what matters and, perhaps, what links the past to the present. As such, if we are to label the 1920s as a “Jazz Age,” or a vividly black “Harlem Renaissance,” then we must also admit that the era was an age of lynching, nativism and Prohibition. If the ’20s brought modernity and human rights to some, it also suffered from the reaction of Protestant fundamentalism and sustained gender inequality. If the 1920s economy began with a roar, we cannot forget that it ended with a crash.

It is in the contrasts that the historian uncovers larger truths. Cheeky labels and generalizations conceal as much as they reveal. An honest assessment of the vital, if misunderstood, 1920s might lead the reader to a variety of intriguing notions, not the least of which is the uncanny—if imperfect—conclusion that the period is connected to our own 21st-century moment in the Age of Trump.

The Jazz Age or the Age of Lynching?

In no era, it seems, has the United States been able to overcome its original sin of slavery, racism and racial caste. It most certainly failed to do so in the ’20s. There were, of course, early signs that the renaissance of black culture following the First World War had strict geographic and temporal limitations. Indeed, the hundreds of thousands of African-American soldiers who deployed overseas during 1917-18 found that the racial and social norms in France were far more open and accepting than those of the United States—especially those in the American South. Some never left France, forming a robust and creative black expatriate community in Paris. Then, when most black soldiers did return home, proudly adorned in their military uniforms, they faced political violence and the threat of lynching at record levels. A number were lynched while still in uniform.

Still, for all these grim intonations, the 1920s was a vibrant era for black culture. Jazz, made popular in the period, is arguably the only true, wholly American art form. The Harlem Renaissance formed by black writers, musicians, poets and critics in New York City would become legendary. The 1920s, in the wake of World War I, was also the start of the First Great Migration of African-Americans from the rural South to the urban North—one of the largest and fastest internal movements of a population in modern history. This shift created the racial pattern and mosaic that modern Americans take for granted. In 1900, 90 percent of American blacks still lived in the South. They left to seek war-industry jobs and postwar urban industrial work. Others hoped to escape the racism, violence and suffocating caste system of the South. Most settled in urban centers in the Midwest and Northeast. Detroit, for example, counted some 6,000 black residents in 1910, but more than 130,000 in 1930.

Blacks still suffered violence and discrimination in their new Northern settings—life above the Mason-Dixon Line was no picnic in the 1920s. For the most part, though, they faced isolation. White families simply moved away when blacks filtered into a neighborhood. Though tragic and racially repugnant, this isolation did indeed usher in a period of African-American cultural rebirth in pockets of the 1920s North, Harlem being the most famous. Jazz performers such as Fats Waller, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong perfected their craft, and “jazz poets” such as Langston Hughes—whose work pioneered and presaged the rap scene of the late 20th century—paved the way for a new, vibrant black literature. In perhaps the biggest surprise of all, African-American artists, musicians and writers became wildly popular with white American audiences and even respected on an international level. Whites devoured black music and culture in a manner, and with a cultural appropriation, that would continue into the present day.

Even so, the Harlem Renaissance had strict racial and spatial limits. The most famous jazz venue, New York City’s Cotton Club—which boasted a house band fronted by Duke Ellington—remained “whites-only” throughout the era. While well-to-do white audiences flocked to the club nightly, the African-American “talent” was forbidden to drink in the club, linger or interact with the white guests. They had to relax and seek their pleasures in neighboring buildings and other clubs in Harlem.

Black political leaders were divided, and they often clashed with each other during the period. Some followed Booker T. Washington in claiming that blacks must temporarily accept segregation in exchange for education and community improvement. Others favored W.E.B. Du Bois, who argued that a “talented tenth” of black leaders must lead the masses in a fight for civil rights. Du Bois helped co-found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which would play a prominent role in the black struggle for equal rights for the next century. Still another segment of blacks supported Marcus Garvey, who preached “Africa for the Africans” and cultural/political separation from white America.

Ultimately, the black civil rights movement of the 1920s stalled. Though the NAACP managed to convince the House to pass the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in 1921, this seemingly simple legislation was rejected by the Senate on more than one occasion and never became law.

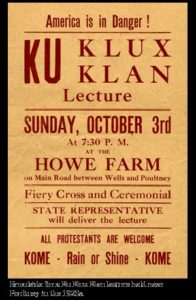

If the 1920s was an age of jazz and flourishing black cultural expression, it was also an age of racial reaction. Unsettled by the growth and popularity of black culture, and incensed by the return of “uppity” uniformed blacks from the war, some whites unleashed a new wave of lynching during the decade. Indeed, the 1920s was also the high tide of popularity for a new manifestation of the Ku Klux Klan. The “new” or “second” KKK emerged in 1915 after a long dormancy after the end of Reconstruction in 1877. This klan expanded its message of hate from a sole focus on African-Americans to a preoccupation with and aversion to Jews, Catholics and certain immigrants. The new klan was also larger and more public than its earlier secretive Southern manifestation. By 1924, it had perhaps 5 million members nationally and undoubtedly many more sympathizers.

The 1920s klan also expanded geographically, becoming extraordinarily powerful and popular in the North. Indeed, during the 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York—a convention that refused to include an anti-lynching plank in the party platform—thousands of uniformed KKK members marched in the streets of the city. The klan was particularly powerful in the Midwest, in Indiana alone counting more than 250,000 members, including the governor. Local klan chapters operated like fraternal orders or social clubs and held public barbecues and rallies throughout the country. The new KKK was also more politically palatable, winning control of several statehouses—Indiana, Texas, Oklahoma and Oregon—north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and with some public officials openly flaunting their klan affiliation.

Perhaps it should come as little surprise that the klan’s numbers exploded during a period of negative eugenics, social Darwinism and scientific racism. Best-selling books like Lothrop Stoddard’s “The Rising Tide of Color Against the White World-Supremacy” posited that the discontent and malaise in America and Europe were due to the influx of the darker races. Many White Americans, and not only those belonging to the KKK, were highly influenced by these pervasive arguments. Indeed, when Stoddard debated W.E.B. Du Bois on a stage in Chicago, thundering that “[w]e know that our America is a White America,” his words carried much popular weight. Thus, while Du Bois handily won the intellectual debate—presciently asking Stoddard, “Your country? How came it yours? Would America have been America without her Negro people?”—it became increasingly clear that philosophical blacks such as himself were definitively not winning the popular contest for the racial soul of the country.

Racializing America: The Immigration Acts of 1917-24

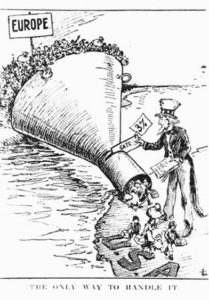

The power of the new klan, the most substantial social movement of the 1920s, was apparent in the strict immigration restrictions imposed throughout the decade. This was something new. For over a century, open immigration—especially from Europe—had been the avowed policy of the United States, a nation that had long prided itself on accepting the world’s “tired, poor, and hungry.” The klan, which was at root a backward-looking organization pining for a time when America was “great” (sound familiar?), influenced a significant segment of the nonmember population, which agreed that the U.S. should be—and allegedly always was—a white Protestant nation. In response to a recent influx of “lesser” Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Southern and Eastern Europeans, WASP America sought to shut the immigration valve—at least for some types of immigrants. This restriction, disturbingly, was wildly popular and easily passed a sympathetic Congress, making the 1920s one of American history’s most intense eras of nativism and immigration control.

White Protestants of the time, and their elected representatives, became obsessed with a cultural program known as Colonial Revival. This movement celebrated the nation’s distant past—a time, supposedly, when Anglo-Saxon Protestantism was the dominant force in American life. Colonial Revival was more than an architectural and fashion phenomenon, and became linked with nativism and anti-immigration sentiment. As the esteemed historian Jill Lepore has noted, both the style and political nativism of the era “looked inward and backward, inventing and celebrating an American heritage, a fantasy world of a past that never happened.” Such reactionary social and political frameworks remain potent forces even today.

Politically, the nativists were victorious and the outcome was a series of increasingly stringent immigration laws, along with the introduction of a new legal category, the “illegal alien,” into the national discourse. All told, the immigration acts of 1917, 1918, 1921 and 1924 reduced the overall level of immigration by 85 percent, slowed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to a trickle, and virtually eliminated migration from Asia and Africa. Then, as now, according to historian Gary Gerstle, immigration “became a policy site onto which Americans projected their fears.” The first act, in 1917, began by excluding any immigrant who could not read—a backhanded method of targeting and limiting the so-called new immigrants, primarily Catholics and Jews from Southern and Eastern Europe, who tended to have lower literacy rates than Northern European migrants. The next act, in 1918, shut out “radical” immigrants—socialists, communists and anarchists—who also tended to make up a larger portion of the “new” immigrants. As Democratic U.S. Rep. Charles Crisp of Georgia put it, “Little Bohemia, Little Italy, Little Russia, Little Germany, Little Poland, Chinatown … are the breeding grounds for un-American thought and deeds.”

Much of the new nativist sentiment was also openly anti-Semitic, as Jews were commonly associated with radicalism and communism because Russian Jews were initially overrepresented in the Bolshevik ranks during that country’s 1917 “Red” Revolution. One U.S. consular official in Romania described the Jewish refugees in Bucharest as “economic parasites, tailors, small salesmen, butchers, etc. … [with] ideals of moral and business dealings difficult to assimilate to our own.” Italians, too, were suspected of having radical ties, which helps explain the controversial trial and execution of the Italian-born anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in a robbery-murder case that captured the nation’s attention in 1920. (They were found guilty even though most of the arguments brought against them were disproved in court. ) Fear of radicals swept the country, becoming most potent, ironically, among congressmen from the South, which had the fewest “new” immigrants in the entire nation. For example, Democratic Sen. Thomas Heflin of Alabama told Congress, “You have it in your power to do the thing this day that will protect us against criminal agitators and red anarchists … you have it in your power to build a wall against bolshevism … to keep out … the criminal hordes of Europe” (emphasis added).

The result was the emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the first open attempt to exclude certain ethnic and racial groups from the U.S. The method was to limit annual immigration from any one country to 3 percent of that country’s population in the U.S. as of the 1910 census. By this calculation, which obviously favored Nordics and Anglo-Saxons, there would be an estimated 80 percent reduction of Eastern and Southern Europeans from the prewar average. President Woodrow Wilson, to his credit, refused to sign the bill, but President Warren G. Harding, Wilson’s successor, would do so in May 1921. And the act worked. The number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe dropped from 513,000 in 1921 to 151,000 in 1923.

But the nativists running the government weren’t satisfied. Still obsessed with the “menace” of Jews, Italians and Slavs, Congress passed the seminal Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, a bill that openly touted the new “scientific racism” of this social Darwinist era. Indeed, the star witness before the House Committee on Immigration was Harry Laughlin, a prominent eugenicist. The committee asked him to study the “degeneracy” and “social inadequacy” of certain immigrant groups, and Laughlin gleefully did just that. Racialist language permeated the debate in Congress, as when Indiana Republican Fred Purnell exclaimed, “We cannot make a heavy horse into a trotter by keeping him in a racing stable. We cannot make a well-bred dog out of a mongrel by teaching him tricks.” West Virginia Democrat R.E.L. Allen doubled down, claiming that the strength of the law lay in “purifying and keeping pure the blood of America.”

The new bill changed the relevant census to that of 1890, a time when even fewer Southern and Eastern Europeans had been in the country. Three percent of that number lowered the annual immigration limit of these ethnic groups to just 18,400, down from the prewar annual average of 738,000. Furthermore, the act, and two Supreme Court decisions, held that all Japanese, Indian and other East and South Asian immigrants must be barred from the United States; the basis of all this was, supposedly, a 1790 law that “reserved citizenship for ‘free white’ immigrants.” Meanwhile, African nations and colonies were allowed only 100 immigrants each per year. Interestingly, Mexican laborers were exempt from the restrictions, though not for lack of prejudice against them. Rather, corporate and agrobusiness interests lobbied against limiting the migration of Mexican peasants and laborers, who were seen as vital to business.

Political restriction of immigrants also influenced cultural norms and laws. Fearing the scourge of “mongrelization” and “miscegenation,” many states hardened laws against interracial marriage. This movement culminated with a 1924 Virginia law that “prohibited a white from marrying a black, Asian, American Indian, or ‘Malay.’ ” Furthermore, this law changed the definition of black from anyone with one-sixteenth African ancestry to any individual with at least one black ancestor, regardless of how remote.

When we imagine the cosmopolitan and open-minded Jazz Age of the 1920s, it is important, too, to recall its hardening of racial lines and the litigious attempts to make America white and Protestant again.

The First Culture Wars: Battles Over the Bible, Alcohol and Modernity

A prevailing mental picture of the 1920s is that of the flapper, sporting a bob haircut, exposed knees and a plethora of jewelry. This “New Woman” drove automobiles, smoked cigarettes and drank alcohol. Surely, we imagine, these female Americans were in every sense “modern,” and representative of an entire era. Only it isn’t so. For every free-spirited flapper, there was a traditionalist wife. And, if there was much imbibing in the ’20s, we must remember this was also the decade of the national prohibition of alcohol manufacture and sales. For every modernist infused with scientific truths, there was more than one Protestant fundamentalist. This, the apposition of the modern and traditional, is the real story of the 1920s—one often omitted from the history books but vital to any comprehensive understanding of the decade.

Prohibition had been a goal of temperance activists (especially women in the movement) for at least three-quarters of a century. The old arguments held that sober citizens—men were the primary targets—were more likely to be diligent workers, faithful husbands, dutiful fathers and better servants of the nation. By the later part of the second decade of the 20th century, prohibitionists had the necessary power in Congress and the state legislatures to push through—over President Wilson’s veto—the Constitution’s 18th Amendment, which outlawed the production and sale (but not the consumption) of alcoholic drinks. This new, powerful wave of sentiment against alcohol spoke to cultural battlefields in America. Pro- and anti-prohibition attitudes tended to cohere with the nation’s growing rural-urban divide. Rural folk tended to support the ban while city dwellers found it intrusive. Prohibition also linked directly to religion and immigration. Many temperance activists favored the ban as an attack on the “un-American” values and mores of immigrant communities, which tended to drink more heavily. It was a matter of social control and another way to make the nation great—and white and Protestant—again.

Known as the “Noble Experiment,” Prohibition created more problems than it solved and lasted only a dozen or so years before its repeal through the 21st Amendment. It was almost impossible to enforce, and bootleggers and speak-easies proliferated around the nation, especially in the urban North. Prohibition—similar to what is happening in today’s “war on drugs”—also turned the production and distribution of alcohol over to criminal elements and syndicates. Organized crime ran rampant in the wake of the 18th Amendment, ushering in a wave of shootings and bombings among rival bootlegging gangs. The most famous gangster was Chicago’s Al Capone, who made tens of millions of dollars and ruled with an iron fist. In one famous incident, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, his men executed nine rival gang members in a busy district in Chicago. The federal government responded, eventually putting Capone away for tax evasion, but Washington never had the resources or ability to enforce the alcohol ban in a meaningful way. The “Noble Experiment” was ultimately a bloody failure. Still, it too reflected the culture wars of the 1920s.

Battles were also fought over the role and scope of women’s public sphere in American life. While many (mostly urban) women shook off the mores of their mothers and embraced the flapper lifestyle, other Americans—(generally rural) men and women—continued to insist the woman’s place was in the home. Though women did finally get the vote in 1920, they did not vote as a bloc—as some had expected or, alternatively, feared—but rather divided along the same political and cultural lines as the male population. Struggles over the role of women were inseparably tied to arguments between country and city, between religion and secularism, and between modernism and traditionalism. So, while more women entered the public sphere and altered their styles, they were still constricted by local “decency” laws that could go so far, as in Washington, D.C., as to regulate the length of bathing suits and dresses down to the nearest inch. Furthermore, after a wartime surge, there were still relatively few women working outside the home. Indeed, contrary to popular imagination, the women’s labor force grew by only 2 percent in the 1920s.

Perhaps the most famous front in the 1920s culture war revolved around the role of religion in American life. Indeed, one can hardly overestimate the power of organized religion in America, from the nation’s very inception. Church attendance and religious adherence in the U.S. is, and has always been, among the highest in the world. For all the sweeping social changes of the ’20s, that remained a salient fact. During the Progressive Era (roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s) and in the decade that followed the end of World War I, an increasingly urbanized, modernized and immigrant population (read: Catholic and Jewish) seemed threatening to many rural, Anglo-Saxon Protestants who saw themselves as the only “real” Americans. In response to the unsettling changes in American society, a new wave of Protestant fundamentalism—specifically the view that the words of the Bible were inerrantly true and were meant to be taken literally—took hold in rural America.

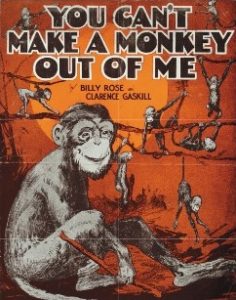

Fundamentalists battled against immigrants, flappers, drinkers and all sorts of modernists throughout the decade. One of the first and most famous battles—one not yet settled, even today—revolved around the question of public education and whether or not teachers should impart the scientific theories of Darwinian evolution to the nation’s students. The battle lines were drawn; all that was needed was a spark to begin the war, and it came in the little town of Dayton, Tenn., in 1925. Tennessee had become the first state to prohibit the instruction of evolution in public schools. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), founded in 1917 to defend conscientious objectors, then located a high school biology teacher in Dayton, John Scopes, who was willing to challenge the law and teach evolution. Scopes was charged with a crime, and the ensuing trial gained national attention, perhaps the first such case to be dubbed the “trial of the century.”

The trial quickly moved beyond the narrow bounds of whether Scopes had violated the law—he clearly had—and became, instead, a battle between the theories of evolution and creationism, between secularism and fundamentalism. And there were other issues, themes and questions raised by the case. First, there was the strong urban-rural divide that tended to cleave along religious and secular lines. And, more saliently, a question of democracy: Could the people of a community ban the teaching of credible scientific theory if a clear majority, such as in most Southern states, didn’t adhere to that science? The secularists framed the case around a question of free speech: Did a teacher have the right to impart a scientific theory that he or she found credible? These were tough issues and still are.

The “Monkey Trial,” as it came to be known, was a national sensation, the first to be broadcast nationwide on radio. Both sides hired celebrity lawyers: for the prosecution, William Jennings Bryan, a three-time Democratic presidential candidate; for the defense, Clarence Darrow, a famed radical litigator who had defended Eugene Debs. For Bryan the trial was all about the “great need of the world today to get back to God,” a question of faith and local (especially rural) sovereignty. For Darrow, perhaps the nation’s most famous litigator, the case was all about reason, science and free speech. Darrow explained his reasons for taking on the case by saying, “I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it—religious fanaticism.”

The climax of the trial came when Darrow put none other than Bryan himself on the stand for a cross-examination regarding the Bible itself. Bryan was deeply religious but no theologian. The crafty Darrow peppered Bryan with tough questions about the supposed infallibility of the Bible and asked whether its words were to be taken literally. Bryan, sweating and confused, struggled through the questioning and seemed to contradict himself with some regularity. Consider just one famous exchange from the trial record that demonstrates the conflict between the two men and their worldviews:

Darrow: You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven’t you, Mr. Bryan? Do you claim that everything should be literally interpreted? Bryan: I believe everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there. … Darrow: You believe the story of the flood [Noah] to be a literal interpretation? Bryan: Yes, sir. Darrow: When was that flood? About 4004 B.C.? Bryan: That is the estimate accepted today. … Darrow: You believe that all the living things that were not contained in the ark were destroyed? Bryan: I think the fish may have lived. … Darrow: Don’t you know that the ancient civilizations of China are 6-7,000 [6,000 to 7,000] years old? Bryan: No, they would not run back beyond the creation, according to the Bible, 6,000 years. Darrow: You don’t know how old they are, right? Bryan: I don’t know how old they are, but you probably do. [Laughter] I think you would give preference to anybody who opposed the Bible.

Everyone knew that Scopes would be found guilty, and indeed he was; his fine was $100, paid by the renowned journalist H.L. Mencken. Still, the trial had much grander, more consequential results. Modernity and science had battled traditionalism and dogma. Though Darrow seemed to get the better of Bryan in their exchanges, there was no clear winner. The cities and the major national newspapers lauded the “victory” of Darrow, but rural America remained stalwart and resistant to evolution and still is. Evangelical Protestant Christianity, after all, remains one of the most potent forces in American political and cultural life.

‘Normalcy,’ Laissez Faire and the Road to the Crash

For the most part the 1920s are remembered as a boom time, an era of unparalleled prosperity and conspicuous consumption. Even the middle and lower classes are thought to have benefited from the soaring economy. And, in a sense, this was true—at least for a while. Between 1922 and 1928, industrial production rose 70 percent, the gross national product 40 percent and per capita income 30 percent. Still, lurking under the surface were troubling signs that prosperity was uneven and, in many ways, little more than a shiny facade. Throughout the decade, some 40 percent of the working class remained mired in poverty, 75 percent of Americans did not own a washing machine and 60 percent couldn’t afford a radio. Forty-two percent of families lived on less than $1,000 a year. What’s more, income inequality reached record highs (which are being matched in the present day), with one-tenth of 1 percent of the families at the top earning as much income annually as the bottom 40 percent of all families.

Furthermore, unions were losing ground throughout the country as newly empowered corporations broke strikes with the backing of government, and, sadly, the public. This occurred despite the fact that working conditions remained deplorable in many industries. Each year in the 1920s, 25,000 workers were killed on the job and an additional 100,000 became permanently disabled because of work-related causes. Given these stunning facts, why was much of the public then so hostile to labor? Partly this reflected an outgrowth of the 1919-21 fear of radicalism known as the Red Scare—the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were destroyed in the postwar years—but it also tied to race and ethnicity. Labor issues became associated with immigrant issues, and, as demonstrated, nativism and anti-immigration sentiments ran rampant in the Roaring ’20s.

Despite these under-the-surface realities of gripping poverty, enough Americans were doing well to such an extent that they could shut out the picture of struggling sharecropping farmers (black and white) and impoverished immigrant industrial workers in the big cities. These suffering people, then as now, were invisible—so long, at least, as general prosperity was the order of the day.

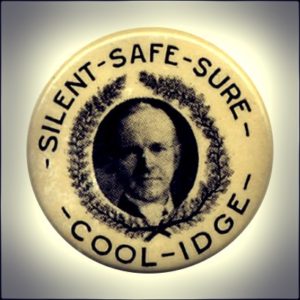

By the presidential election of 1920, the Progressive Era was dead. Sick of centralized government social reforms and soured by the experience of war, a majority of Americans turned their backs on liberal revisionism. What these citizens wanted most of all was to turn the clock backward to what they imagined was a simpler time, before the war, and even before the progressive turn in American politics—a time, they imagined, of liberty, autonomy and freedom from government interference. The Republican candidate in 1920, Warren G. Harding, rode to victory on this tide of conservatism and anti-progressivism. On the campaign trail, Harding promised a return to “normalcy,” by which he meant the retreat of the federal government from a reform agenda and a reintroduction of laissez faire economics. In Boston in May 1920, Harding summed up his view of the future by asserting, “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment … not submergence in internationality, but sustainment in triumphant nationality.” And it was precisely this reactionary—and ultimately corrupt—agenda that Harding would pursue in the White House.

Harding and his two Republican successors—Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover—would cozy up to big business and corporations. Harding made clear his intentions in his inaugural address. “I speak for administrative efficiency, for lightened tax burdens … for the omission of unnecessary interference of government with business, for an end to the government’s experiment in business,” Harding proclaimed in a clear repudiation of the progressive agenda. His successor, Coolidge, who famously proclaimed that “the business of America is business,” bragged toward the end of his term, “One of my most important accomplishments … has been minding my own business. … Civilization and profits go hand in hand.” An older brand of Republican, Theodore Roosevelt, would have probably been disappointed in his party’s new agenda. T.R., the famous trust-buster, had always believed that spreading out economic opportunity and avoiding the monopoly of wealth was essential to the long-term prosperity of the nation. But that was a different time; T.R. was a progressive, of sorts—and most Americans now rejected such government activism. They would pay the price.

Harding appointed Andrew Mellon, the fourth richest man in America, as his secretary of the treasury. Mellon, who served for many years, including under Coolidge, would upend the entire edifice of progressive social and economic reformism. During his tenure, Congress would exempt capital gains from the income tax and cap the top tax rate—an early form of what is now labeled “trickle-down economics,” in which the wealthiest Americans receive the lion’s share of tax cuts. The top income brackets would see their tax rates lowered from 50 percent to 25 percent, while the lowest bracket was given a much smaller cut, from 4 percent to 3 percent. Hoover, who was secretary of commerce before serving as president (1929-33), believed in voluntary associationalism, the theory that government should encourage corporations to work together and reform working conditions, all absent federal regulation. It didn’t work. (It rarely does. Consider the 2008 financial crash as exhibit A.) What the reign of Mellon and Hoover did do was tie federal power to private corporate interests. The Wall Street Journal summed up the situation: “Never before, here or anywhere else, has a government been so completely fused with business.”

Indeed, in a contemporary landmark study, “The Modern Corporation and Private Property” (1932), the authors concluded that a “corporate system” had “superseded the state as the dominant form of political organization.” Big business liked it that way and launched new publicity campaigns intended to demonstrate that corporations had a “strong social conscience,” and that government-provided social welfare was unnecessary and ill-advised. With money came immense advertising power, on a scale that could not be matched by working-class interests. It remained to be seen whether profit-driven corporations could responsibly guide the massive U.S. economy in the absence of federal oversight. It’s an experiment that has been tried—and has failed—throughout American history and remains popular among certain political factions.

This spreading political and social gospel of materialism also affected American culture. As historian Jill Lepore wrote, “During the 1920s, American faith in progress turned into a faith in prosperity, fueled by consumption.” Americans spent more than they earned, paid with credit and rode the runaway train of an economy that was sure to crash. Only no one seemed to see it coming. When Hoover accepted the 1928 Republican nomination for the presidency, he predicted—barely a year before the stock market crash—that “[w]e in America are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land.” He would soon eat these words. None of it was sustainable—the mushrooming stock market or the growing wealth disparity. In a prescient article, “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” F. Scott Fitzgerald captured the absurdity of the moment, writing, “It was borrowed time anyway—the whole upper tenth of the nation living with the insouciance of a grand duc and the casualness of chorus girls.” And, as in the first minutes after the Titanic struck an iceberg, the rich carried on just as before.

The depression would be the worst in American history. When the crash came, it came hard and fast. A decade’s worth of irresponsible, risky financial speculation—altogether unregulated by the feds—had created a bubble that that few had recognized. As the expert John Galbraith wrote in his study of the crisis, “The Great Crash,” the 1920s economy was “fundamentally unsound” and the “bad distribution of income” contributed to the onset of deep depression. Over just three weeks after the initial stock market crash, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell from 326 to 198 and stocks lost some 40 percent of their value. Hoover’s initial, and prevailing, instinct was to work with business to right the economic ship. Within weeks of the crash he invited corporate leaders to the White House in an effort to coordinate a response. Nothing of substance was forthcoming; the corporations still clung to the profit motive and were unwilling to bend for the good of the country. As the historians Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle have concluded, “All in all, the corporate rich failed miserably to meet their responsibilities toward the poor.” This fact was readily apparent, but, still, Hoover balked at any strong federal response.

Hoover tried to reassure Americans, but beyond cajoling corporations to take responsible (voluntary) actions he was unwilling to meaningfully intervene. He believed charity was the best way to ameliorate rising poverty but opposed any form of government relief, arguing that to provide such help would see the nation “plunged into socialism and collectivism.” The obtuse and heartless response of a generation of Republican politicians and corporate leaders reads today as cruel farce. When, by 1930, half the 280,000 textile workers in New England—Coolidge’s home region—were jobless, the former president commented simply, “When more and more people are thrown out of work, unemployment results.” Then, in early 1931, Coolidge again showed his flair for understatement: “The country is not in good condition.” Henry Ford, perhaps America’s most famous business leader—and, incidentally, an anti-Semitic admirer of Adolf Hitler—claimed in March 1931 that the Depression resulted because “the average man won’t really do a day’s work unless he is caught and cannot get out of it. There is plenty of work if people would do it.” Weeks later, Ford would lay off 75,000 workers.

Only making matters worse, President Hoover fell back on his protectionist instincts and severed the U.S. economy from Europe with a new tariff act in 1930. Other nations, predictably, retaliated with trade restrictions of their own and world trade shrank by a quarter. By 1932, one in five U.S. banks had failed, unemployment rose from 9 percent to 23 percent, and one in four Americans suffered a food shortage. The very foundation of liberal-capitalist democracy seemed to be crumbling. The New Republic magazine proclaimed, “At no time since the rise of political democracy have its tenets been so seriously challenged as they are today.” The Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini predicted that “[t]he liberal state is destined to perish.”

These premonitions were understandable at the time. Millions of Americans—out of work and desperate for food and shelter—gathered in temporary outdoor camps, dubbed “Hoovervilles,” and increasingly became radicalized, drawn either to the communist left or the fascist right. One thing seemed certain: The fate of global democracy seemed to hinge on the ability of the United States, the world’s largest economy and democracy, to find a middle way that mitigated poverty without a turn toward left- or right-wing totalitarianism. That would require American voters to send the likes of Hoover and his failed ideology packing and elect a different sort of candidate with fresh ideas on how to confront the crisis of the Great Depression. That man was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When he took power in 1933 it was uncertain whether he, and American liberal capitalism, would endure.

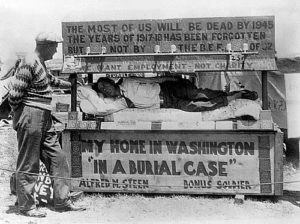

An American Crime: The Bonus Army March on Washington

It is by now the platitude of platitudes: Americans love their military veterans, adulating them today (though vacuously) at every turn. Only it wasn’t always so. In fact, one could argue that there exists a long, highly American trend—dating back to the underpaid and underfed Continental Army of the Revolutionary Era—of asking the world of our veterans in war and then, predictably, ignoring their postwar needs. There is perhaps no better example than the suppression of the Bonus Marchers in our nation’s capital in the spring and summer of 1932. This, to be sure, must count as a great American crime.

The controversy centered on the redemption of the promised federal bonus certificates given to the millions of veterans of the First World War. Most of these bonuses could, by law, be redeemed only far in the future, around 1945. But, for hundreds of thousands of jobless, homeless American combat vets, that simply wouldn’t do. They were hungry now, they were cold now. A Great Depression was on the land, and many of these vets demanded the payout immediately. Ironically, later Keynesian economists argued that paying out this large sum of money would actually have acted as a stimulus to the depressed American economy—but this was decidedly not the prevailing theory of the day among business-friendly Republicans such as President Hoover. He flatly refused the payout.

In the spring of 1932, some 20,000 veterans, carrying their bonus certificates, converged on the national capital. They promised to stay put until their demands were met, and they set up makeshift camps across Washington, D.C. On observer, the famous writer John Dos Passos, observed that “the men are sleeping in little lean-tos built out of old newspapers, cardboard boxes, packing crates, bits of tin or tarpaper roofing, every kind of cockeyed makeshift shelter from the rain scared together out of the city dump.” It was a sad scene and an embarrassing fall from grace for these proud war vets. When the bill to pay off the bonus failed in the Senate—it had passed the House—most of the “Bonus Army” stalwartly stayed put. In response, Hoover coldly ordered the active-duty Army to evict them—a highly questionable use of the Posse Comitatus Act, which prohibits the use of the regular Army to suppress disorder within the nation’s borders.

The next day, four troops of cavalry, four companies of infantry, a machine gun company and six tanks gathered near the White House, all under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur’s aide de camp that day was future general and president Dwight Eisenhower, and future general and World War II hero George Patton commanded one of the cavalry troops. This was not their finest hour. MacArthur personally led his troops—all wearing gas masks—down Pennsylvania Avenue as they fired tear gas to clear the vets out of old buildings, some of which were set on fire by the advancing troopers. Thousands of Bonus Marchers, along with their women and children, frantically ran. Soon the entire encampment was ablaze. The whole tragic affair was over rather quickly. The day’s toll: two veterans shot to death, an 11-week-old baby dead, an 8-year-old boy partly blinded, and thousands more injured by the tear gas.

The brutality was swift, and, make no mistake, it was purposeful. Then Maj. Patton gave the following instructions to his troops before the assault: “If you must fire do a good job—a few casualties become martyrs, a large number an object lesson. … When a mob starts to move keep it on the run. … Use a bayonet to encourage its retreat. If they are running, a few good wounds in the buttocks will encourage them. If they resist, they must be killed.” How quickly Americans would forget this man’s despicable role in this national disgrace in favor of memories of his actions in World War II. The vets did not get their hard-earned and much-needed bonuses that day. What they received was the violent rebuke of a government that had abandoned them to poverty and despair. The famed journalist H.L. Mencken captured the moment ever so perfectly, writing, “In the sad aftermath that always follows a great war, there is nothing sadder than the surprise of the returned soldiers when they discover that they are regarded generally as public nuisances.” For an impoverished generation of World War I veterans, this was the thanks for their service.

* * *

Even at the time, not everyone bought in to the mythology and consumerism of the Roaring ’20s. Some cultural critics—artists and writers in particular—saw through the hollow facade of American life and society. These were the men and women of the “Lost Generation,” those damaged and horrified by both the horrors of the Great War and disgusted by the materialism of the proceeding decade. Though their prose remains on the curriculum for students throughout the nation, their assessment of the dark underbelly of the decade has not stuck. Americans, it seems, prefer the clichéd labels of “Jazz Age” and “Harlem Renaissance” to the inverse realities of the nativism, lynching, Prohibition, fundamentalism and social control so prevalent in the decade that “roared.”

Ernest Hemingway, a wounded veteran of the First World War, wrote in his acclaimed novel “A Farewell to Arms” (1929), “The world breaks everyone. … But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially.” Indeed, Hemingway, like so many others in his “Lost Generation,” chose exile as an expatriate in Paris to life in consumerist America. His fellow “lost” author, F. Scott Fitzgerald, also critiqued the era and expounded upon the disillusionment of many veterans, writing in “This Side of Paradise” (1920), “Here was a new generation … dedicated more than the last to the fear of poverty and the worship of success; grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.”

Indeed, there was among many Americans (especially urbanites of the middle or upper class) a “worship of success” and materialism infusing the 1920s. This is the way we tend to imagine and reconstruct the decade in our minds—a time of energy and movement toward modernity—forgetting Fitzgerald’s rejoinder: that the period carried a loss of faith, a fear of poverty, a battle between ideologies and, yes, between competing images of what it meant to be an American. The 1920s gave birth to a national culture war, perhaps America’s first. Open a newspaper, flip on the news—no cease-fire yet.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works: • Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle, “Ruling America: A History of Wealth and Power in a Democracy” (2005). • Gary Gerstle, “American Crucible: Race and Nation in the 20th Century” (2001). • Jake Henderson, “History Brief: Roaring Twenties” (2016). • Jill Lepore, “These Truths: A History of the United States” (2018). • Howard Zinn, “The Twentieth Century” (1980).

Maj. Danny Sjursen, a regular contributor to Truthdig, is a U.S. Army officer and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir and critical analysis of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives with his wife and four sons in Lawrence, Kan. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his new podcast, “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris “Henri” Henrikson.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author, expressed in an unofficial capacity, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.