Arctic Ocean Could Be Ice-Free Before Midcentury

By 2050, humans will have added enough carbon dioxide to earth's atmosphere to melt all the Arctic’s sea ice, researchers predict.

By Tim Radford / Climate News Network

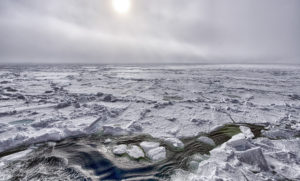

The average American is responsible for the melting of almost 50 square meters of ice per year. (Christopher Michel via Flickr)

LONDON, 5 November, 2016 — Two scientists have worked out what it would take to melt all the ice in the Arctic Ocean.

If their sums are right, then by the time human beings have burned enough fossil fuels to add 1,000 billion tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, the Arctic Ocean will be free of ice in September — the annual minimum — and the world’s shipping will have a new, safe, fast route across the Arctic Circle.

Quite when this moment will happen depends entirely on the rate that humans add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. But the two researchers calculate that for every metric ton of carbon dioxide emitted, the Arctic will lose 3.3 square metres of sea ice.

Melt rate

That means the average American, with the world’s highest use of fossil fuels per head, is now melting almost 50 square metres a year.

Right now, humanity in total is releasing 35 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere each year, so the 1,000-billion-ton mark will be achieved before mid-century, and the north polar ocean ice will drop for the first time below 1 million square kilometres, leaving the Arctic almost entirely open sea.

Climate scientists predicted years ago that — at present rates of melting — the Arctic could be ice-free in September by mid-century. What Dirk Notz of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg in Germany and Julienne Stroeve of the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, in the US, report in the US journal Science is that they have established a direct correlation between emissions and ice loss.

They looked at the average area of sea ice every September for the last 30 years — since satellite instruments began to deliver accurate data — and matched that against the cumulative carbon emissions for the last three decades.

The two call the relationship “robust”: there might be all sorts of reasons why over a long historical period Arctic sea ice would vary from year to year, but as greenhouse gas levels rise, CO2 becomes the dominant force that makes the ice retreat.

This year the ice began melting with great rapidity, and according to the NSIDC the area of frozen sea dwindled to an average of 4.72 million square kilometres, the fifth lowest in the satellite record. It is now freezing again, very fast.

Arctic waters

But the US Office of Naval Research reports that it has already begun to explore the open waters. Researchers this summer began measuring the strength and intensity of waves and swells moving through the increasingly weakened sea ice. They also used acoustic sensors to test the conditions for sonar operations and antisubmarine warfare.

That is because the retreat of the ice opens up new commercial shipping lanes, makes possible greater oil and gas exploration and new fisheries — and new challenges for the US Navy’s surface fleet. The goal is to understand the changing conditions.

“Abundant sea ice reduces waves and swells and keeps the Arctic Ocean very quiet,” says Robert Headrick, who manages the research programme.

“With increased sea ice melt, however, come more waves and wind, which creates more noise and makes it harder to track undersea vessels.”

Tim Radford, a founding editor of Climate News Network, worked for The Guardian for 32 years, for most of that time as science editor. He has been covering climate change since 1988.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.