‘Black Is Beautiful’: Identity, Pride and the Photography of Kwame Brathwaite

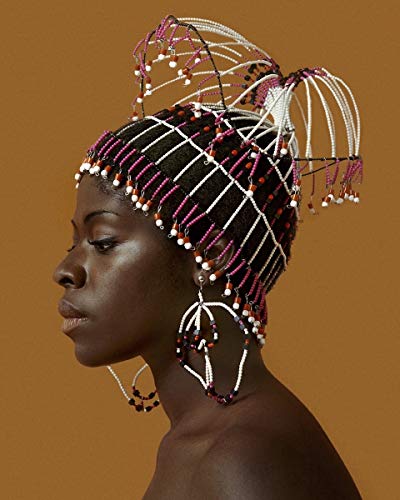

A new look at the activist impresario and photographer provides a positive guide for building community. Kwame Brathwaite's photo of Nomsa Brath wearing earrings designed by Carolee Prince, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1964. (Courtesy of the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles.)

Kwame Brathwaite's photo of Nomsa Brath wearing earrings designed by Carolee Prince, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1964. (Courtesy of the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles.)

2019 National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Award: Third Place, Commentary Analysis/Trend—Books/Arts

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

On an evening in the early 1950s on the corner of 125th and 7th Avenue in Harlem, two teenage brothers named Elombe Brath and Kwame Brathwaite stood in the crowd to hear Carlos Cooks speak about Pan-Africanism and the legacy of Marcus Garvey. Cooks’ message of black pride and a vibrant history dating to the beginnings of mankind was part of a tradition of corner speakers rooted in radicalism dating to Garvey himself and peers like Hubert H. Harrison, A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen and W.A. Domingo. Cooks’ words stayed with the brothers, none more than one elegant truth: “Black Is Beautiful.”

A few years later, Kwame and Elombe went on to co-found the African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS), a collective of artists, playwrights, designers and dancers, giving African Americans a way to share and celebrate their culture unmolested by a monolithically white racist society. From AJASS they launched Naturally ’62, a fashion event celebrating black women and the African American aesthetic. Out of it came “Black Is Beautiful,” a mantra for a generation.

“Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite,” at Los Angeles’ Skirball Cultural Center through Sept. 1, covers the photographer’s early years documenting jazz concerts and cultural events organized by him and his brother.

“He didn’t just propel the Black Is Beautiful movement forward with his iconic imagery, he created a template on how to bring a community together around an anthem of positivity and inspire an entire generation to love themselves during a period of segregation, when the world was telling them not to,” is how Skirball managing curator Bethany Montagano sums up the show. “He used his photography as a vehicle for social change and that definitely comes out in the exhibition. But the exhibition is also a road map on how to do it.”

Kwame and Elombe started AJASS mainly because they loved jazz. “They couldn’t get Miles [Davis], but they could get all the people who played with Miles. They brought Paul Chambers,” says curator Kwame Brathwaite Jr., who speaks regularly with his 81-year-old father at his home in New York City. “It was a place where you could have African Americans enjoy jazz in their neighborhoods rather than deal with the club barriers and things going on downtown and in Manhattan.”

When a local photographer came by selling images from their shows, Kwame became captivated and decided he would teach himself photography. On display are over 40 black-and-white images, some as large as 5 feet square, of everyday people as well as jazz legends like Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln and Dizzy Gillespie, or Art Blakey taking five with a smoke and a drink, as well as the women of Grandassa Agency, a modeling firm that featured black women—some professional models, others off the street—representing a variety of body shapes and skin tones.

Named for Grandassaland, Cooks’ description of an ancient Africa before continental drift, the Grandassa models, Naturally ’62 and especially the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” resonated beyond Harlem and into mainstream culture. The “Naturally” shows continued on a regular basis over the years, capturing the styles of the times and taking to heart Cooks’ own heckle of some smart-looking female passersby, “Your hair has more intelligence than you. In two weeks, your hair is willing to go back to Africa and you’ll still be jivin’ on the corner.”

“Hooking jazz photography with the social action and activism, then he was able to put women on the frontlines,” Montagano says, laying out Brathwaite’s guide to implementing change. “The teachings of Marcus Garvey recognize equity between men and women. Something that’s very distinctive about Kwame Brathwaite’s work is that women and men have equity. And this is also some of the first positive imagery of African American women, where their hair is worn naturally, they don’t wear makeup. That’s a huge disruption in photography at the time.”

An original Grandassa model known as Black Rose was a stylist who wound up teaching how to style and care for natural hair, rather than getting it straightened as so many did in the 1950s and early ’60s. Brathwaite showed an uncanny prescience in understanding the power of photography to shape people’s worldview. Seeing African Americans denigrated by a monolithic white society and media, he used his camera to refocus how they saw themselves.

“They were trying to convey a message to the Garveys, their own following, through this thing that they called edutainment,” says Brathwaite Jr. of his father’s agenda. “It was specifically to make sure ideas of pride and unity came across when they were doing these shows.”

Not in the exhibit are works that came later, shots of Bob Marley and Marvin Gaye, as well as The Jackson Five on their 1974 trip to Africa, and Muhammad Ali, a longtime friend of Brathwaite, in the Congo that same year in the days leading up to his “Rumble in the Jungle” with George Foreman. The Champ sits alone, pensive, in the quiet after a meeting with the press.

“It’s by far one of the most poignant moments of him dealing with whatever he was dealing with in his life, but this kind of peaceful, quiet, muted Ali, which is rare to see cause he’s always on when cameras are around,” observes Brathwaite Jr. Even as his father became known among celebrities in the ’60s and ’70s, he continued to photograph everyday people, placing the famous on equal footing with Harlemites celebrating at the Garvey Day parade.

“He didn’t take a violent approach, he didn’t take a hateful approach, he took an approach about bringing everybody back to self-love. And I think that’s what makes it so dynamic,” concludes Montagano, referencing the new monograph on Brathwaite’s work by Aperture available May 1. “Kwame and the story behind his photography and the way he was able to bring his community together offers a template to young people on how they do it in a way that’s accessible and positive. The scholarship and the fact that this provides such a great model for anyone viewing this today when faced with this struggle are two of the most important parts of this exhibition.”

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.