In America, Being Poor Can Cost a Fortune

The superrich won't acknowledge that lower-income earners are caught in an expensive, vicious cycle. Mars Hill Church Seattle / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Mars Hill Church Seattle / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

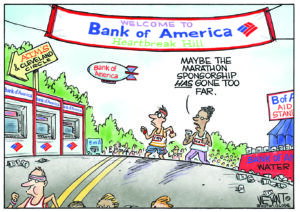

The ink is barely dry on a trillion-dollar tax cut for multinational corporations, and one of its largest beneficiaries is already looking for more. Earlier this month, Bank of America announced it would be applying a $12 monthly surcharge for e-banking, a policy that disproportionately affects its poorest customers. For lower-income earners, it’s merely the latest reminder that trickle-down economics don’t really trickle down, and that being poor can be extraordinarily expensive.

E-banking at BOA had been free provided customers didn’t use tellers and agreed to receive their monthly statements online. But effective Jan. 19, 2018, clients will have to either maintain a minimum balance of at least $1500, or receive monthly direct deposits of $250 or more to avoid a fee. According to a private report by Goldman Sachs, BOA enjoyed a $21 billion profit last year and will be paying an estimated $3.5 billion less in taxes in 2018 thanks to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which lowered the U.S.’ corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent.

The too-big-to-fail bank’s greed has sparked outrage. As of January 28, a Change.org petition opposing the surcharge had received more than 115,000 signatures. Kristen Clarke, president and executive director of Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, has warned that BOA’s actions will discourage the poor from maintaining traditional bank accounts. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation reports that 7 percent of U.S. households were unbanked in 2015, and alternatives for the poor can often prove even more costly.

In an official statement on the BOA fee, Clarke asserted, “Poor people who are denied access to traditional bank services are left vulnerable to costly check-cashing outlets, pawnshops and other predatory services. By pushing poor people into the dark world of alternative financial services characterized by higher fees and exorbitant interest rates, low-income communities are at risk of being thrust into further economic distress.”

The predatory fees charged by banks, payday lenders and check-cashing establishments are only a few of the ways in which poverty can cost a fortune in the U.S., where the poor are socked with expensive auto insurance, high-interest car loans and exorbitant health care rates.

Research from the Harvard School of Public Health finds that healthier food costs $1.50 more per day on average than less healthy food. As a result, the poor often purchase canned goods loaded with preservatives and containing huge amounts of salt and refined sugar. This can save money in the short term but become costly when one develops major health problems like diabetes, heart disease, obesity and cancer. Eating healthy on a budget is not impossible, but preparing healthier meals can be time-consuming. And when the poor are working two or three low-paying jobs, some of which may demand a lengthy commute, time is of the essence.

Typically, America’s poor have longer, more expensive commutes, and are more reliant on increasingly neglected public transit systems. In many parts of the U.S., mass transit is vastly inferior to the systems in Europe, Australia or Japan. If the poor aren’t losing time and money waiting for busses that run irregularly—assuming their area even has public transit at all—they are driving older cars in need of costly repairs.

The auto insurance industry is notorious for discriminating against the poor by charging them higher rates based on education and job status. The people who can least afford higher insurance rates are the ones who often end up paying them, while those from upscale areas tend to enjoy the lowest rates. In 2017, a ProPublica/Consumer Reports study on auto insurance in California, Texas, Illinois and Missouri found that rates were 30 percent higher in predominantly non-white zip codes than in whiter areas with comparable accident costs. On top of that, the poor often pay higher interest rates on car loans.

The credit scoring industry, along with banks and insurance companies, also does its part to keep the poor in poverty. Lower-income earners are more likely to have lower credit scores, which can inhibit one’s ability to purchase auto insurance, rent an apartment and even secure a job.

It’s a vicious cycle. America’s poor are slammed with costly banking or check-cashing fees, face higher auto insurance premiums and are more susceptible to health problems, yet the one thing that can be improve their material circumstances—a decent job—can be denied to them based on their credit score. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) has proposed making it illegal nationwide for employers to run credit checks on job applicants, and a handful of states have already followed through.

America’s poor are more likely to remain poor today than they were in the 1950s or 1960s. According to a 2016 report by Raj Chetty and other economists, 30-year-olds in 1970 had, on average, a 90 percent chance of earning more than their parents at the same age, adjusted for inflation. In 2016, about half of 30-year-old millennials were earning less than their parents were the generation before.

Anti-poverty programs were a prominent part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. But since the 1980s, the U.S. has embraced the failed policies of trickle-down economics, which have not only made it more difficult for the poor to escape their circumstances but have caused a huge segment of the middle class to slide into poverty.

The U.S. desperately needs to move away from neoliberalism through aggressive anti-poverty and job-training programs, a national minimum wage of $15 per hour and the strict regulation of its banking sector. Only then will Bank of America face real consequences for gouging its most vulnerable customers.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.