Can the World Bank’s New CEO Change Their Toxic Lending Practices?

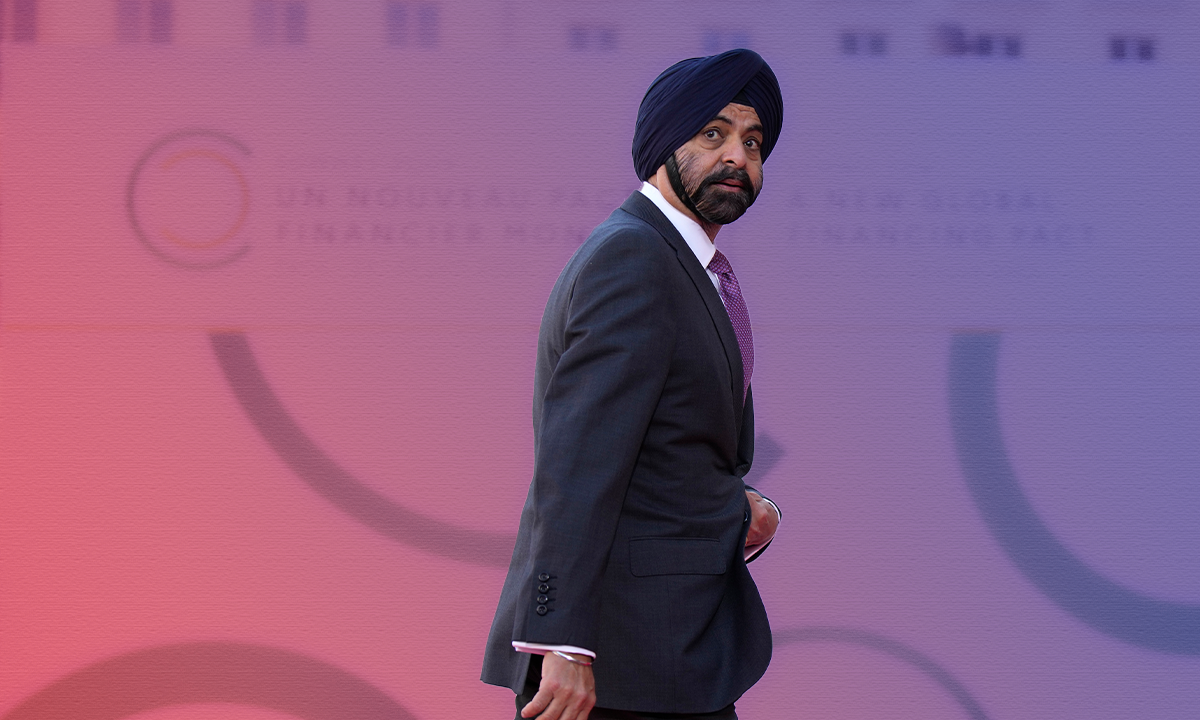

Ajay Banga and the façade of accountability in global development finance. Ajay Banga wants you to believe a new day has arrived for the World Bank and its lending practices. Image: AP Photo/Lewis Joly. Graphic: Truthdig

Ajay Banga wants you to believe a new day has arrived for the World Bank and its lending practices. Image: AP Photo/Lewis Joly. Graphic: Truthdig

On a glorious afternoon in Paris this June, the Eiffel Tower haloed behind him in a haze of sunlight, Ajay Banga, the World Bank’s new president, laid out his blueprint for saving humanity. “I have a chance [to] adopt a new vision and a new mission with the World Bank,” 63-year-old Banga told several thousand young people who had gathered for the Power Our Planet concert. “That vision is simple: create a world free of poverty on a livable planet.”

Banga had been invited to Paris as part of the Summit for a Global Financing Pact, a conference to establish a climate financing system convened by French president Emmanuel Macron. Macron’s name, when mentioned by one of the concert’s other speakers, provoked a jeering roar of boos from the youthful crowd. Banga, at least, seemed more conscious of the audience — and even aware of the negative past influence of the bank he’s been charged with running.

Poor countries, he said, “should feel the hand of the World Bank on their back, not in their face.” He went on to detail for the concertgoers a plan to extend temporary debt relief to nations that had experienced natural disasters.

One could be forgiven for thinking Banga’s apparent self-awareness signaled a transformation at the influential global development bank. He is the first person of color to run it, and for this fact alone he has received glowing media coverage. The previous president, Trump-appointed David Malpass, had resigned from the institution a year early amid a storm of controversy following his refusal to acknowledge fossil-fuel-driven warming. “I’m not a scientist,” Malpass told a reporter at a New York panel, having dodged a question about whether he believed in climate change. A wave of relieved analysis and celebratory op-eds followed the announcement this spring that the Biden administration had tapped Banga to replace Malpass. (As the bank’s largest shareholder, the U.S. government historically chooses the institution’s president).

Recruiting corporations to avert ecological catastrophe has been central to Banga’s climate-fighting pitch.

“He Could Uncork Trillions to Help Save the Planet,” The New York Times enthused in May. “The West should pay heed to Ajay Banga,” counseled the Financial Times. An anonymous administration official told Politico that President Biden believed Banga “has the track record and the know-how to rise to the occasion and make sure the World Bank delivers for the globe.” Banga, one analyst told the Times, “probably has more wind in his sails for reform than any [World Bank] president has had in modern times.”

His plans for how to do that already seem clear. “The only way [to fight climate change] is to get the private sector to believe that this is part of their future,” Banga told CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, in an inaugural TV interview after his appointment in June.

Recruiting corporations to avert ecological catastrophe has been central to Banga’s climate-fighting pitch. But for critics of the bank, his private-sector approach to green development, a field in which he’s never before worked, is the ineluctable result of his past at Nestlé, PepsiCo, CitiBank and Mastercard. What, for some, is cause for celebration — Banga’s past in corporate finance “makes him extra capable to take on our climate crisis,” according to President Biden — is for others reason for suspicion.

“Banga is out-and-out from the corporate world,” Sushovan Dhar, an Indian political activist from Mumbai, told Truthdig. Dhar sees Banga’s appointment not as a departure from the norm but an extension of a long tradition in which a U.S. citizen with experience in international corporate finance is selected — part of a “gentleman’s agreement,” in his description.

“Banga simply does not have any experience in climate,” said Dhar. “But something that Banga has always managed in his life is to ensure profit for his masters, wherever he is employed. I’m sure he’ll do the same for the World Bank: seek new avenues for investment.”

Investment in the private sector, of course, has long been one of the bank’s core development strategies since its founding in 1944. It has poured billions of dollars into corporations across the Global South involved in mining, agribusiness, infrastructure, health care and schools, primarily through its private-lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Some of those loans have ended in egregious abuses of human rights, embezzlement, predatory finance schemes, damage to air, water, soil and wildlife, and poisoning of whole communities. Environmental laws have been skirted, massacres of striking workers abetted, death squads allowed to operate — all under the eye of the IFC and the World Bank.

In March, while Banga was busy on a global charm offensive, meeting heads of state and business leaders, the European Network on Debt and Development published an open letter, co-signed by 71 organizations, that rejected his appointment, and declared his experience in transnational corporate finance to be insufficient:

A Wall Street veteran, with no demonstrated development experience, Banga lacks the credibility to lead the World Bank in its stated objective of promoting sustainable development and eradicating poverty, or in addressing economic and social rights of the most vulnerable communities, let alone climate change.

His appointment, said the petition, was part of a wider strategy to divert public funds to private finance. The authors were particularly concerned with Banga’s current and past positions on the boards of equity firms invested in fossil fuels.

“Ajay Banga has a pretty weak record when it comes to even saying he’s going to address climate change,” said Kate DeAngelis, an international finance program manager at Friends of the Earth, who focuses on ending financing for fossil fuel exploration. “There’s a bunch of folks in power who love to say that they’re going to fight climate change through the private sector. But we see the private sector as being driven, at its core, by profit, so that means overlooking the environment.”

An early indication of how he will proceed came with a June memo that Banga sent to the Bank’s 16,000-person staff. He asked them to “double down” on development while slashing approval time for projects, so that the bank can pump out loan money more quickly and efficiently. “The process is overly elaborate and subject to multiple review mechanisms,” he said, and this “not only cost[s] valuable years but erode[s] staff ambition.”

“I know exactly what that means,” said Michelle Harrison, a human rights lawyer and deputy general counsel at EarthRights International who has represented communities fighting industrial projects supported by the World Bank. “It means cutting due diligence. It means getting rid of protections that make sure the environment and local communities don’t get screwed by IFC.”

Banga rose from humble origins. The son of a Sikh officer in the Indian army, he started as an intern at Nestlé, where he stayed from 1981 until 1994. He then joined PepsiCo, where he helped shepherd the introduction of Pizza Hut and KFC to the subcontinent. The trajectory of the early years of his career reflected tectonic economic shifts in India as it welcomed multinational corporations amid the transition to neoliberalism.

His endurance in business paid off, and he soon moved to the big leagues of high finance, joining CitiBank in 1996, where he became CEO of the Asia-Pacific region. By the early 2000s, he had emigrated to the U.S. and become a naturalized citizen, and oversaw North American consumer banking for CitiGroup during the same period it came under scrutiny for mortgages and credit cards it offered. In 2007, he took the helm at MasterCard. During his decade-long tenure as CEO of the financial behemoth, profits multiplied six-fold, and market capitalization ballooned from $30 billion to $300 billion, reflecting in part his focus on emerging markets. Banga became extremely wealthy as a result: though numbers vary, the most common estimate of his net worth as of 2021 was $206 million. (Banga’s office did not respond to interview requests for this article.)

The sleek global conferences where the titans of finance convene — he’s received with a solicitous reverence usually reserved for a head of state.

After leaving the company in 2021, he became vice-chairman of General Atlantic, one of the world’s largest private equity firms, as well as chairman of Exor, a Dutch holding company valued at $31 billion — two of the most high-profile examples in an illustrious roster of corporate board positions. Topping this off was the appointment in 2021 by Kamala Harris to be a co-chair of the Partnership for Central America, a coalition of private investors overseen directly by the vice-president. The group’s goal was to stem “root causes” of migration through spurring investment by transnational corporations such as Nike, Nestlé, Chobani Yogurt and Mastercard.

The power he now holds as president of the World Bank means that when he goes to G20 and G7 summits, to Davos and Aspen — the sleek global conferences where the titans of finance convene — he’s received with a solicitous reverence usually reserved for a head of state.

It’s hard to overstate the sway of the World Bank. Along with the International Monetary Fund, it’s considered one of the most powerful financial institutions in the world.

On paper, its ostensible mission is two-pronged: to “end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity in a sustainable way.” Though other lending banks gained steam in the 2010s — primarily those operating out of China — the World Bank’s influence remains outsized. It was founded in tandem with the IMF at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference to set rules that would stabilize the functioning of the global capitalist system after the catastrophe of the Second World War. Since then it has dispensed across the world, and in the Global South particularly, many billions of dollars for development projects ranging from mining, to infrastructure, to agribusiness, schools and health care projects — both to governments as well as, increasingly, private corporations.

The bank has the power to structure and restructure debt owed by low-income countries, which was estimated to have run into the trillions at the beginning of the 2020s. With the International Monetary Fund, it has overseen the design and implementation of so-called “structural adjustment programs,” or SAPs. Structural adjustment programs — privatization of state industries, deregulation of economies and the promotion of export-oriented and extractive industries — lay at the heart of globalization. In many instances, citizens of countries where they’ve been applied have not welcomed structural adjustment, and backlash against the programs has led to riots across the Global South when basic social services such as health care and public transport, newly privatized, were rendered out of reach for millions of people.

In the United States, discontent over the globalization agenda culminated in the 1999 Battle of Seattle, when anarchists, unionists and environmentalists converged on the city to disrupt that year’s round of global trade negotiations overseen by the World Trade Organization. Fearful police exploded in violence, tear-gassing and beating protesters, some of whom responded with rocks and bottles, and the National Guard was called in to suppress any further resistance. “In the annals of popular protest in America,” journalists Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair wrote in their book about events that November, “these have been shining hours, achieved entirely outside the conventional arena of orderly protest…This truly was an insurgency from below.”

The revolt in Seattle forced the World Bank to reckon with the dislocation, pain and suffering that a decade of privatization of public services had produced under the regime of structural adjustment. There was a brief moment of reform in 1999, as the bank launched initiatives to provide debt relief to heavily indebted poor countries.

At the Paris climate financing summit in June he announced the first of his major public initiatives for the World Bank

But the bank’s policies in the 2000s and 2010s, repackaged in glossy new language, continued to be anchored in the faith that private interest and profiteering will translate always into improved human welfare — that the alleged efficiency of corporate capital should be allowed to supersede the crusty bureaucracy of the state. Instead of structural adjustment programs, the World Bank began touting “blended finance” and “public-private partnerships” (PPP), in which the bank used its money not for direct financing of development projects but instead provided “technical assistance” to “de-risk” those projects for private capital. Ultimately, the goal was to convince corporations that it’s safe and profitable to make an investment that would yield a good return. Between 2002 and 2012, according to one analysis, financial support for PPPs more than tripled.

Banga’s emphasis on marshaling the private sector to the cause of fighting climate change is in keeping both with this long history and with the stated priorities of the World Bank’s largest shareholder. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen — who, as chief of finance for the United States, has an inordinate influence over the bank’s operations — told reporters in April that the U.S. has scant plans for investing more public funds into the bank. “We’re not requesting a capital increase at this time.” Instead, she said, it should “more creatively stretch existing resources” by “[getting] more private funding opportunities.”

The bank was already heeding Yellen’s counsel. A December 2022 white paper titled “Evolving the World Bank Group’s Mission, Operations, and Resources: A Road Map,” repeatedly invokes the private sector as playing “an essential role in addressing climate mitigation.” The World Bank Group, the report states, can “do more to mobilize and enable private sector solutions” while also “unleash[ing] private sector growth” in developing countries. It advocates the creation of an IFC-managed financing fund to help spur development in poor countries through “sustainable private sector solutions.” Public funding, referred to as “scarce,” should be depended on only when “private sector engagement is not optimal.”

Banga is dutifully following this path. At the Paris climate financing summit in June he announced the first of his major public initiatives for the World Bank: the Private Sector Investment Lab, which he declared “a crucial piece of the puzzle” for fighting the climate crisis. The lab would bring together 15 CEOs and financiers to marshal private capital to the cause of World Bank-sponsored green development projects. The members of the new group included Noell Quinn, the CEO of HSBC Bank; Feike Sibesjma, the CEO of Dutch-investment company Royal Phillips; and Larry Fink, billionaire CEO of U.S.-based BlackRock, which has over $8 trillion in assets and is one of the world’s largest investors in fossil fuel companies.

BlackRock’s loyalties are clear. “We will continue to invest in and support fossil fuel companies,” states a January 2022 letter signed by BlackRock’s head of external affairs, Dalia Ross, written in response to grassroots outcry over the company’s investments in fossil fuel extraction in Texas.

Fink has cultivated a green public image, going so far as writing an op-ed in 2021 for T he New York Times in favor of climate action. “Multilateral institutions like the I.M.F. and the World Bank are often criticized for being too slow to adapt when faced with crises,” he wrote, advocating to “push international bodies to overhaul their approach to climate finance for poor countries.” But his decisions as CEO belie his rhetoric: as of 2019, $87 billion of BlackRock’sportfolio was in fossil fuels.

“We are perhaps the world’s largest investor in fossil fuel companies,” BlackRock’s January, 2022 letter reads. “As a long-term investor in these companies, we want to see these companies succeed and prosper.” The company also owns 8.8 million shares in Brazilian agro-business behemoth Bunge, which is responsible for large swathes of Amazonian deforestation.

As it chokes off public funding while deepening its relationships with corporate finance, the IFC has midwifed an astonishing number of environmental and human rights abuses—and these have almost all ended up victimizing the poor.

One of the most notorious cases is that of Dinant, a Honduran palm oil corporation that received $15 million from the IFC to develop its plantations. According to a 2017 civil lawsuit against the IFC, the palm oil company was accused of hiring “paramilitary death squads and…assassins” to kill, disappear and brutalize members of ‘campesino,’ or peasant farmer groups, who were occupying lands they alleged Dinant had stolen from them in the 1990s and early 2000s. Private security operatives contracted by Dinant, armed with military assault rifles and patrolling alongside uniformed soldiers and police, were singled out in a 2013 report by a U.N. working group as the most cited offenders in a string of assassinations many saw as a terror campaign. “The working group was profoundly disturbed at the alleged involvement of private security guards in the killing, disappearance, forced eviction, and even sexual violence to which peasants have been subjected in Bajo Aguán,” the report read.

Even as the lawsuit against the IFC for financing Dinant remains in limbo, killings that are carried out with total impunity continue to occur, targeting land defenders who challenge Dinant in plantation regions of Honduras. At least five members of cooperatives in conflict with Dinant or their family members have been killed this year. One leader of a cooperative in conflict with Dinant, Omar Cruz, was assassinated with his brother-in-law on Jan. 18 after delivering a formal complaint to the government alleging that Dinant was financing an armed group called Los Cachos. Hipolito Rivas, a land defender from a cooperative that had retaken land from Dinant was murdered alongside his 26-year-old son, Javier, after continued threats from a paramilitary group with alleged ties to the Honduran military. (Dinant has repeatedly denied accusations of links to the murder, calling on the authorities for investigations into the killings).

At least five members of cooperatives in conflict with Dinant or their family members have been killed this year.

In the Indian state of Gujarat, in 2008, Tata Power received $450 billion from IFC to construct a 4,150 megawatt coal-fired power plant. The decision to proceed with financing flew directly in the face of the IFC’s own prediction that “improper mitigation or insufficient community engagement” could produce “unacceptable environmental impacts.”

What had been forewarned came to pass. The biodiverse Mundra coast, inhabited for centuries by Muslim subsistence fishermen and home to mangroves and coral reefs, was swept with environmental destruction on a Biblical scale. The power plants discharged vast, industrial-scale plumes of steaming hot water into the estuaries, wiping out mangrove forests and killing the fish populations that local inhabitants depended on for sustenance.

The adulteration of groundwater with salt became so intense that many crops ceased to grow. Clouds of ash from the plant, and particularly from a nine-mile conveyor belt built next to villages to carry imported Indonesia coal to the plant, settled over the dying coastal landscape, ruining the fish left out to dry and leading to severe respiratory problems, including among children.

In 2015, represented by the environmental law practice EarthRights International, three communities affected by Tata Mundra sued the IFC in U.S. federal court. The IFC asserted it had “absolute immunity” from prosecution under the International Organizations Immunity Act (IOIA), arguing that losing such immunity could “produce a considerable chilling effect on IFC’s capacity and willingness to lend money in developing countries” and open “a floodgate of lawsuits by allegedly aggrieved complainants from all over the world.” In 2019, the Supreme Court denied this argument of immunity in a 7-1 decision, though lower courts stated the IFC was immune on other grounds.

Or consider the case of Lonmin, a now-defunct London-based mining giant acquired in 2019 by mining giant Sibanye Stillwater. Lonmin operated a 33-square kilometer platinum mine in Marikana, South Africa. The IFC provided Lonmin a $100 million loan while also investing $50 million in equity shares, some $15 million of which was earmarked for improving the living conditions of the workers of the mine.

The workers, Black migrants far from their families, had been living in wretched conditions —“worse than 19th century,” in the words of South African sociologist Patrick Bond — and the $15 million was supposed to fund the construction of 3,200 new houses, creating a “comfortably middle class” living standard, according to Lonmin’s CEO, Brad Will.

But only three such houses were built, and in 2012, to protest the conditions, the workers went on strike. The day after Lonmin’s CCO told the South African minister of mines to “bring the full might of the state to bear on the situation,” South African police massacred 40 strikers. The massacre did not stop the IFC from taking up yet more shares in Lonmin later that year. A report by the IFC’s internal watchdog was lukewarm in denouncing Lonmin’s complicity in the lead-up to the massacre, instead writing off the “violence… in the context of increasing tensions between rival unions in the mining sector in South Africa, mines being shut down, worker lay-offs and declining worker bonuses.” It did not recommend any disciplinary action.

“There’s this total facade of accountability,” Michelle Harrison, the EarthRights International lawyer, told me. Following the Tata Mundra case, “one of the most scathing reports comes out” — about Lonmin, and another about Dinant — “and the IFC responds and says: We don’t care. It really shows the culture at the IFC, and to a broader extent, at the World Bank Group.”

South Africa offers a clear view of Banga’s record on development when he was in the private sector at the helm of Mastercard. In 2013, he signed on to a sweeping financial inclusion project in South Africa that was sponsored by the IFC. The World Bank defines financial inclusion as a system that ensures “individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs — transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance — delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.” The financial inclusion project that Banga helped make happen in South Africa ended up as a predatory finance scheme and ultimately collapsed in bankruptcy.

In 2013, the South African government proposed contracting the private sector to digitize welfare payments using state-issued debit cards. In the context of massive economic inequality, the program was designed to provide monetary support to unemployed youth, the elderly and the disabled. The winner of the bid was a data services company called Net1 Technologies.

Banga, who in 2010 had declared a “War on Cash”— a war “preferably processed by Mastercard,” as a New York Times profile noted — proposed that his company provide cards for the project, which would be secured through biometric registration. (White parliamentarians, parroting racist tropes that Black and colored grant recipients would scam the system to get multiple checks, had pushed for the biometric security overhaul). In 2016, the IFC announced it would invest $107 million.

Net1’s putative success has become part of Banga’s small personal mythology of accomplishments in development, most of which have centered around the push for a cashless world.

Representatives for Net1 drove to the remote shantytowns where recipients for cash transfers lived. Registering their fingerprints, the representatives convinced the recipients to sign up for “financial services” — funeral insurance, internet access, microinsurance, loans — that would be automatically deducted from the accounts into which the welfare grant was transferred. There was often no informed consent as to the ramification of these services — the exorbitant interest rates, the inability to default on the loans. Even the fact that recipients had to pay for the various services went unmentioned.

The result was that the original grant disappeared, hoovered away by automatic deductions of non-negotiable loans and repeating service fees. The grant’s original purpose of supporting people incapable of working disappeared too. Grantees now lost control over their finances. Net1’s opaque digital interface made it all but impossible for them to understand what had happened to the money.

Dr. Erin Torkelson, a geographer and lecturer from the University of Western Cape, called the program a “major financial coup.” By outsourcing the welfare program to Net1, she said, a social safety net intended to provide unconditional assistance to vulnerable members of society was transformed into a system to facilitate predatory loans and other forms of financial trickery and abuse. Before the company collapsed in bankruptcy in 2018, Torkelson spent years assisting victims of the financial scheme in mostly futile quests to reclaim their money.

Net1’s putative success has become part of Banga’s small personal mythology of accomplishments in development, most of which have centered around the push for a cashless world. When The Washington Post asked him why he focused on bringing these services to poor countries, Banga let slip a refreshingly honest response. “I’m not a philanthropist [sic],” he said. “I’m not a United Nations agency. I run for shareholders. I have to do well.”

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.