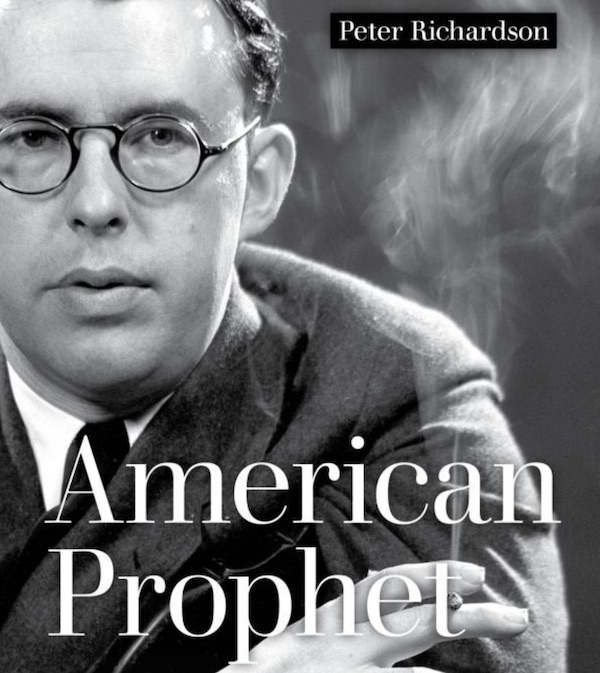

Carey McWilliams: The Most Important American Author Many Don’t Know

Biographer Peter Richardson talks with us about the activist-writer's extraordinary career and how he inspired others to do their best work. University of California Press

University of California Press

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Truthdig contributor Peter Richardson is the author of “American Prophet: The Life and Work of Carey McWilliams,” now out in paperback from the University of California Press with a foreword by Mike Davis. We asked him about Carey McWilliams and his achievements.

Truthdig: Your book traces the extraordinary career of Carey McWilliams, from his Los Angeles legal activism to his radical journalism and finally to his two-decade editorial stint at The Nation. You argue that he was one of the most versatile and productive public intellectuals of the 20th century. Why don’t more Americans know about him?

Peter Richardson: Yeah, it’s funny. Despite the accolades, he’s probably the most important American author that most people have never heard of. He has his fans, of course. Kevin Starr was one. He called McWilliams “the single finest nonfiction writer on California—ever” and “the state’s most astute political observer.” Mike Davis is another. “City of Quartz” is a kind of love letter to McWilliams. Over the years, McWilliams also won over the city room at the Los Angeles Times. When journalists need a quote about the city, they often turn to McWilliams or Joan Didion.

There are a few reasons McWilliams isn’t better known. First, he was a radical. He had powerful enemies, including J. Edgar Hoover, the Los Angeles Times and the Associated Farmers, which objected to his history of California farm labor in “Factories in the Field” (1939). When Earl Warren first ran for governor in 1942, he promised growers that his first act would be to fire McWilliams from his position in state government. The California Un-American Activities committee smeared him mercilessly. So even though he was accomplishing a great deal, he didn’t endear himself to those in power.

McCarthyism was a factor. By the 1950s, McWilliams was back in New York City, shepherding The Nation magazine through a difficult decade. Many of his friends were victims of the Communist witch hunt—in fact, McWilliams wrote a book on that topic in 1950, well before most people understood the dangers to our democracy. But that was typical of McWilliams. He was always a kind of early-warning system. In 1950, he called Richard Nixon “a dapper little man with an astonishing capacity of petty malice.” It took the rest of the country two more decades to figure that one out.

Finally, his style didn’t call a lot of attention to itself. His arguments were clear, fact-based, and hard-hitting. A 1944 Supreme Court opinion cited him four times on the Japanese internment. Other writers admire the clarity and power of his prose. He made it look easy, and professional writers know that it’s anything but that. He never went in for fireworks, but that’s probably one of the reasons that his work holds up so well now.

TD: You mentioned the Japanese internment during the Second World War. Did McWilliams write about other forms of racial and ethnic discrimination?

PR: Very much so. In fact, that’s one of the reasons he was always in trouble. He wrote a book in 1943 called “Brothers Under the Skin” that documented the histories of America’s minority populations. After it came out, reactionaries in the state legislature grilled him on the subject of interracial marriage, which was still illegal. He hadn’t written about that issue, but when he said he opposed those laws, they reported that his answer was consistent with the Communist Party line.

Click here to read long excerpts from “American Prophet” at Google Books.

He also wrote “A Mask for Privilege,” a book about anti-Semitism, and “North From Mexico,” which was a very important book on Latinos in the Southwest. At that time, there were very few works on that topic. Throughout the 1940s, he wrote almost one first-rate book per year.

He was also active in the community. He organized the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee after a group of Latino youths were railroaded for murder. That decision was overturned, and it’s still regarded as the Latino community’s first political victory in Los Angeles. He also helped calm the city during the Zoot Suit Riots, which was really a military riot that escalated after a scuffle between sailors and Latino youths in downtown Los Angeles. All of that material went into “North From Mexico,” but it also inspired “Zoot Suit,” the play and film written by Luis Valdez.

TD: You write that McWilliams wrote a Supreme Court brief for the Hollywood 10, the screenwriters and producers who were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and convicted for contempt of Congress.

PR: Right, but that case never got to the Supreme Court. McWilliams knew most of those guys from his political activism in and around Los Angeles. He was also close with Robert Kenny, one of their lawyers, who ran for governor in 1946. McWilliams dedicated one of his most important books, “Southern California Country,” to Kenny that year.

McWilliams’ amicus brief was part of his larger effort to defend Americans who held perfectly legal but unpopular political views. Ironically, one of McWilliams’ editors—Angus Cameron at Little, Brown—was caught up in that. He was forced to resign as editor in chief for publishing left-wing authors like McWilliams. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the Harvard historian, led the charge against him and McWilliams, who never forgave Schlesinger. Cameron didn’t land another editorial job until the 1960s, when Random House hired him.

TD: Wasn’t Angus Cameron also Hunter S. Thompson’s editor?

PR: Almost. Cameron offered Thompson a contract for “Hell’s Angels,” but Thompson ended up signing with Ballantine, which published the paperback edition. Then Random House published the cloth edition, but Thompson worked with Jim Silberman. In the meantime, Cameron and Thompson exchanged some really interesting letters about the nature of Thompson’s work.

McWilliams played a big role in all of this. In fact, he gave Thompson the story idea in the first place. Thompson was living in San Francisco and desperate for freelance assignments. McWilliams asked him to cover the Hells Angels and then ran his story in The Nation. Almost instantly, Thompson began receiving offers for a book-length treatment. “Hell’s Angels” became his first best-seller, and he acknowledged McWilliams on the dedication page.

After that, Thompson kept in close touch with McWilliams, probably hoping he would supply another great story idea. Douglas Brinkley, who edited two volumes of Thompson’s correspondence, said that McWilliams was the only editor whom Thompson really admired.

TD: How would you describe McWilliams’ editorial work at The Nation generally?

PR: He had a reputation for being right on the big issues, especially civil rights and Vietnam, and he was very clear about Nixon’s shortcomings. He also kept an eye on Ronald Reagan while he was running for governor. Even then, McWilliams was talking about dog-whistle politics, especially on the issue of discriminatory housing.

Probably the most important thing McWilliams did at The Nation was convert it into an outlet for investigative reporting. It’s much easier for magazines to run opinion and analysis, but McWilliams gave several writers the space to pursue bigger stories. By the late 1960s, muckraking was back in style, but McWilliams kept it going when most outlets were content to publish the government’s lies about Vietnam, for example.

TD: You point out that McWilliams really had two constituencies—those who read his books, and those who knew his work at The Nation.

PR: Right, and those two audiences didn’t usually intersect. When he went east to edit The Nation, he stopped writing books, so his California audience thought of him as an author in exile. Most of his readers (and colleagues) at The Nation weren’t familiar with his books. They saw him as the steward of a venerable magazine.

I think McWilliams modeled his career after H.L. Mencken, his boyhood idol, so it made sense for him to dedicate his energies to editing a magazine. But the 1950s was a terrible time to manage a left-wing magazine, and the 1960s ushered in a new kind of politics that didn’t play to his advantages. I love what he did at the magazine, but in some ways, The Nation’s gain was the country’s loss.

TD: Last question. What was the coolest thing you learned about McWilliams while researching his life?

PR: I suppose it was finding a letter in McWilliams’ archive from Robert Towne, who wrote the original screenplay for “Chinatown.” In the letter, Towne explained that a single chapter from one of McWilliams’ books—“Southern California Country,” published in 1946—inspired Towne’s effort, which won an Oscar in 1975. The chapter was about the region’s water politics. In addition to exposing the history of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, McWilliams was way ahead of his time in terms of environmental awareness. Anyway, Towne took that history and turned it into a Southern California epic. One of the fascinating things about McWilliams—who took a lot of criticism for what I regard as his decency and sanity—is how he inspired so many others to do their best work.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.