Casey Anthony and Why We Need to Fix Capital Punishment

The case of the newly freed Anthony points to how our capital punishment system is marred by gender-based discrimination that both unfairly benefits and unfairly burdens female offenders. The U.S. capital punishment system both unfairly benefits and unfairly burdens female offenders.

… This is a man’s world But it would be nothing, nothing without a woman or a girl.

— James Brown

In May 2010, long before Casey Anthony had become the protagonist in a national morality play and long before CNN Headline News hosts Jane Valez-Mitchell and Nancy Grace had assumed the role of a latter-day Greek chorus calling for her conviction, Anthony’s defense team brought a pretrial motion to remove the death penalty as an option in the case on grounds of gender discrimination.

Andrea Lyon, a DePaul University law school professor and a prominent critic of capital punishment, argued the motion. Lyon, who later withdrew from the defense reportedly for financial reasons, relied on the research and in-court testimony of University of New Mexico law professor Elizabeth Rapaport, a leading expert on the subject of women and the death penalty. Lyon contended that Anthony had been charged with capital murder not because of the facts of her child’s death but because women who kill loved ones are often exposed to a higher degree of punishment than men charged with similar offenses. Judge Belvin Perry Jr. denied the motion, finding no specific evidence of gender bias.

The remainder of the case descended into TV history, culminating in Anthony’s stunning acquittal on all homicide charges. As anyone with a pulse and an Internet connection knows, the outcome has prompted a round of post-trial retrospectives bordering on mass hysteria, ranging from Grace’s charge that the verdict sent the “devil dancing” to former O.J. Simpson prosecutor Marcia Clark’s analysis that the jury had been brainwashed. And now that Anthony has been released, the hysteria can be expected to continue at least for the next several news cycles.

But no matter where one stands on the verdict — and there are valid reasons to criticize it or to conclude, as did the jury, that the state of Florida had failed to meet its constitutional burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt — the question of whether our system of capital punishment is inherently marred by gender-based discrimination has been lost in all the noise. The short answer is that the system is fundamentally flawed, but in a contradictory manner that both unfairly benefits and unfairly burdens female offenders.

To understand this paradox, it’s helpful to review a little legal history. Back in the heyday of capital punishment in the 1930s, when justice was swift, mercy was in short supply and an average of 167 inmates were executed annually, juries in most states were given unlimited discretion to decide whether a capital defendant upon conviction would live or die. Not surprisingly, the ultimate penalty was disproportionately imposed on the poor and racial minorities, especially black men and especially in homicide cases involving minority defendants and white victims.

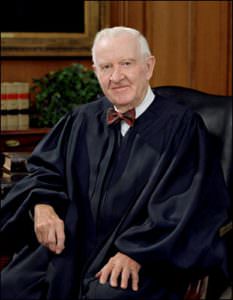

Although the regime of unfettered discretion met its demise with the Supreme Court’s 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia, the court stopped short of declaring the death penalty unconstitutional. Indeed, four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia, it endorsed the current system of “guided discretion,” which requires that death penalty statutes set forth objective criteria relating to the defendant’s character and criminal record, to help jurors and judges decide which offenders should be condemned and which spared. In the process, it was hoped, the otherwise arbitrary and capricious nature of capital punishment would be curbed, if not eliminated.

When it comes to race, the new system has proved to be an abject failure. According to the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center, since 1976 more than three-quarters of the murder victims in cases resulting in execution were white even though whites made up roughly only half of all victims. In California, one study has shown that those who killed white people were three times more likely to be sentenced to die than those who killed blacks and four times more likely than those who killed Latinos. In Texas, where there have been some 470 executions since 1976, there has been but one involving a white murderer and a black victim. (See “Death Penalty, Still Racist and Arbitrary,” an Op-Ed article published in The New York Times this month.)

When it comes to gender, the record is more ambiguous but no less arbitrary. Along with professor Rapaport, the leading researcher on women and the death penalty is Victor Streib, who until his retirement last year taught law at Ohio Northern University. Among other findings, Streib reports that since 1976, women have accounted for 10 percent of annual murder arrests but only for 2 percent of death sentences and a mere 1 percent of those actually executed. As of late 2010, there were 55 women on death row nationwide out of a total population of 3,261.

The numbers, Streib’s work suggests, support the conclusion that with one pivotal exception, when it comes to gender, the death penalty is a man’s world that arbitrarily discriminates against men and in favor of women. The exception, as Rapaport has chronicled, concerns domestic homicides. While nearly half the women on death row in the United States have killed family members or intimates, a mere 12 percent of condemned men in six states studied by Rapaport were domestic killers. And of the male domestic killers sent to death row, nearly half had killed after being left by a wife or girlfriend while more than two-thirds of the female domestic killers were condemned not for being jilted but for killing for pecuniary gain. “Here,” writes Rapaport, “is the most abhorred female domestic crime: Dependence turned to gall and greed; trust betrayed; love and duty mocked.”

Casey Anthony was a perfect fit for the paradigm. In connection with its gender-discrimination motion, the defense argued that the state of Florida originally had decided against seeking the death penalty but changed course only after learning that Anthony had licensed a set of photos and videos to ABC for $200,000, which she used to pay her legal expenses. Throw in Anthony’s alleged motive of wanting to shed her child to pursue a party lifestyle—the fabled bella vita—and a capital trial was all but inevitable.

But for a weak record based solely on circumstantial evidence and a sequestered jury that was insulated from media hype and vitriol, Anthony today might very well be the second woman currently on Florida’s death row instead of a newly freed celebrity. Eventually, as her notoriety fades, we may remember her as someone who escaped justice or as someone who was overcharged with capital murder by overzealous prosecutors. Or we may use her case as a long-overdue occasion to re-examine our system of capital punishment that treats whites differently from blacks and women differently from men.

No matter how much we tinker with it, the system is broken and beyond repair. It should be scrapped.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.