‘Caspian Rain’

Truthdig is pleased to present these two excerpts from the novel "Caspian Rain" by Gina Nahai, best-selling author of "Moonlight on the Avenue of Faith." In "Rain," her fourth novel, Nahai explores Iran's complex culture through the eyes of a group of memorable characters living in various sectors of society during the years leading up to the Islamic Revolution.

“Caspian Rain” Excerpt 1:

ALL SUMMER LONG, Chamedooni watches our house. He hovers around our front door with his suitcase full of promises, stands at the corner bus stop like a sentry at his station. He lets the buses come and go without climbing into any of them because he’s too busy keeping an eye out for the boy with the bicycle. At night, he hides behind the shutters in his darkened bedroom and watches me.

People say that in his youth, Chamedooni was a “person of substance.” He comes from a family of crypto Jews in Mashad — a city in northeastern Iran where, in the mid-nineteenth century, the entire Jewish community was forced to convert to Islam. After that, the Jews practiced their religion in secret, aware that if discovered, they would be put to death. To keep from assimilating, they promised their children to one another at birth and married them off at very young ages, so that generations later, even after they had been liberated from their oath of conversion, Mashadi Jews were surrounded by an aura of remoteness and mystery that set them apart from Jews in other parts of Iran.

After the Second World War, Chamedooni’s father brought his family to Tehran and opened a rug and antiques business. They lived in an alley off Cyrus Street, but the store was on Ferdowsi Avenue, which was popular with British and French and American “advisers” who were sent to Iran mostly to tell the Shah how to run the country. Compared to other Jewish young men in South Tehran, therefore, Chamedooni lived a privileged life.

He was further blessed when, upon finishing high school, he passed the college entrance exam which was deliberately designed so the greatest majority of applicants would fail. Chamedooni was not among the smartest students in the land; everyone knew this. He didn’t have a father who could buy him a place on the admissions roster. And he certainly wasn’t good-looking or charming enough to have ingratiated himself to one of the powerful women in the Shah’s inner circle. How he had burrowed his way into university remained a mystery even to his parents, until he had been there for a year or two, and demonstrated, by the way he got himself into some very public trouble, that his being admitted was nothing less than God’s design — that He arranged this merely to ruin Chamedooni’s life and bring eternal grief to his family.

First, he declared that he was going to study sociology — as if that were something you needed to go to school to learn. It’s a scam, I tell you, why can’t a person just look around and glean whatever he needs to know about “society,” for God’s sake? What kind of a job does that get you anyway? Other people’s sons are becoming doctors and engineers, what are we supposed to say when someone asks what our son is doing with his life? Say he’s studying society?

Undaunted by his parents’ opposition, Chamedooni made matters worse by joining every student organization that would have him. Against the dire warnings of his elders — sooner or later they’ll remember you’re a Jew and stab you in the heart — he accepted invitations to lunch and dinner and all-day hikes with Muslim friends. He went to other kinds of gatherings as well — secret ones where young men and women read the works of Marx and Lenin and called the Shah “a Western lackey” and an “American stooge.” He even brought home some of the leaflets handed to him at those gatherings — something that scared and offended his parents beyond their wits. They reminded him that the Shah was the best thing that had ever happened to Iranian Jews; that he had protected and defended the Jews at his own peril. They also reminded him of the secret police who watched every citizen in every corner of the country and certainly in Tehran, of all the spies who were spread across schools and universities, who rode taxis and ate in restaurants, shopped in stores and worked in factories only so they could report the smallest infraction — a word, a book, even the appearance of disloyalty — against the regime.

The secret police — SAVAK — had earned its reputation by living up to and often exceeding every citizen’s worst fears, and it did not fail to catch up with Chamedooni either. One morning in the third year of his studies at university, two men in tailored suits and Italian ties picked him up off the street and drove him to be interrogated at “an undisclosed location.” For months after that, his parents looked for him all over town and in the city morgue as well. They knew without needing to be told that their son was being held by the military police. It happened all the time — a person vanishing off the street, only to turn up months later, dead and floating in a river, or with a dozen bullet holes in his face and chest, or hung by the neck from a helicopter. Sometimes, the “missing” would be tortured but not killed, so they could go home and spread the word about what had happened to them, scare other foolhardy souls who may be tempted to defy the Shah’s rule. Chamedooni never spoke of the eleven months and nine days he had spent in solitary confinement in a basement at Evin prison, but you could tell, just by looking at him, that he had suffered great horror and, in the process, lost half his mind. He went in a young man with too much confidence and a sense of invulnerability; he returned paranoid and imbalanced, unable to hold down a job or tolerate living with anyone else, convinced that he was under surveillance every minute of the day.

He couldn’t live with his parents because he was sure the house was surrounded, and he couldn’t work in any one place because that would make it easier for SAVAK to find him. He moved into The Tango Dancer’s because he believed the rumors about her being an undercover Nazi doing the bidding of foreign governments, and therefore thought she would be immune to prosecution by SAVAK. Even then, he continued to be obsessed with the memory of other prisoners he had met during his ordeal, and so he went looking for them at the morgue every day.

At the morgue, he met many people with many sorrows, and that is where he got the idea of selling “cures” for every ailment that afflicted humanity. He began collecting herbs and pills and heavily perfumed oils to remedy physical illness, prayer scrolls and talismans and little bottles of blood from sacrificial beasts to tend to emotional needs. He hunted for books and letters, phone numbers of hard-to-find professionals in uncommon fields. He kept a log of policemen who could be bribed in every neighborhood, of hospital nurses who would agree to raise a dying patient’s dose of morphine without express permission from the doctor.

For one of those patients — a woman who had lost all her hair and lay in bed looking like an overgrown fetus in a cotton gown — he agreed to find a wig. The woman had red hair, which wasn’t common, and didn’t look natural in synthetic fiber, so Chamedooni went to the morgue and started searching. He knew the importance of hair to a woman’s chastity. He knew about Samson and his powers, about the ghouls and warriors in Persian mythology who could be summoned instantaneously if a single strand of their hair was set on fire. What he didn’t know was that he would fall in love with the young girl whose hair he stole that first time, that he would go looking for her long after she was buried and her hair had been made into a wig. He didn’t know that, in time, he would become obsessed with seeing the pale faces and naked bodies of all the other girls who lay, prone and supine — his to admire or mourn, rob or grant mercy to — all over the morgue. He gave a few hundred rials to the indigent undertakers who washed and minded the dead, and then he was free to roam around — the charming prince in a sleeping kingdom — but he didn’t realize that he would carry the dead with him when he left, see them in his sleep and waking life, seek the texture of their hair and skin in everything he touched.

He didn’t realize that they would haunt him — those women who were forever denied entry into paradise because Chamedooni had defiled them — and that sometimes, they would bring with them their dead sons and husbands and still, Chamedooni would go looking — for that red-haired girl he had stolen from, and for all the other ones as well. That he would look for them — contrite and repentant — hoping to restore for them the piety he had taken away, and that he kept taking away from others, in spite of his own best intentions.

HE DIDN’T KNOW, then, that the door would close.

He didn’t know that fires would rage in the night — ten million fists waving in the air, black banners hanging from every rooftop, red carnations in the barrels of every soldier’s gun while, behind closed doors, priests in black robes laughed at the folly of a people who, given the choice, had opted for servitude over freedom.

We are a people who believe in God.

He didn’t know — my father when he left me waiting for him that morning in Tehran — that the borders of our country would soon close, making it impossible for him to return or for me to join him in America. That the Shah, believed invincible only months earlier, would escape the country only to wander the globe, looking for a new home. That mobs of terrified Iranians would storm the airport in Tehran, press at its gates hoping to escape, and find them locked. Through the chain-link fence, they would see planes sitting idle on the tarmac, lined up, motionless — like little aluminum toys. Within months the black banners on people’s rooftops would become veils on their women’s heads; the red carnations in the soldiers’ guns — offerings from the rebel mobs who had called the soldiers “my brothers,” had convinced them to switch sides — would adorn the graves of young men and children sent to fight Saddam Hussein’s soldiers. And all along, the mullahs in black robes would deliver to those who defied them precisely the kind of justice — swift and deadly — that they had promised. Hiding in their homes, the people who had invited the mullahs to rule the nation would suddenly realize why, when given the choice between the Shah and the mullahs, they had opted for the greater of the two evils.

We are a people who believe in God.

He didn’t know that the mullahs would divide — men from women, foreign from native,Muslim from Sunni — the world in order to conquer all; that they would divide the sea: they would draw cables across vast portions of the Caspian, hang sheets, like the sails of a sinking ship, that would separate men from women as they bathed. The wind would lash at the sails, rip them off, and carry them away, but soon, they would be replaced.

We are a people who believe in God.

Even years later, after the borders had reopened, my father would find it impossible to come home without risking his life and freedom. He was a Jew who had lived too long in America; he could have been a Western spy; he certainly qualified as Zionist; he might have been arrested, tried, and convicted in one of the mullahs’ sham tribunals: two hours long, without evidence, or attorneys, and then the accused would be taken onto the roof, and shot. I don’t think he would have left Iran without me had he known we would never see each other again. I don’t think he would have given me up so easily had he known it was forever.

You can define a person by his actions, or you can define him by the choices he would have made had he been aware of his options.

I don’t blame Omid for leaving us to go to America with Niyaz. I don’t believe he chose his allegiances, that he had a chance, really, to do right by his wife and child. But I do blame him for denying Bahar the independence he so adored in Niyaz, and I blame him for lying to me before he left.

I lost my father the same way I lost my hearing, the same way I lost my mother’s trust: they slipped away when I wasn’t looking, without warning or explanation, until each absence became a link in a chain of questions that would go unanswered and prayers that never stood a chance.

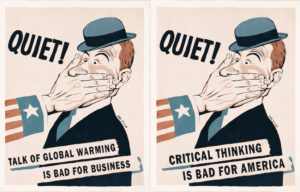

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.