Chile in Their Hearts, and Ours

The recent book by John Dinges pursues the untold story behind the killings of two Americans by the Chilean military after the 1973 coup. An unidentified member of the bodyguard detail of President Salvador Allende mounts a machine gun on a balcony of the presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, in an attempt to protect the president during the coup led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet on Sep. 11, 1973. (AP Photo/Alberto Bravo)

An unidentified member of the bodyguard detail of President Salvador Allende mounts a machine gun on a balcony of the presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, in an attempt to protect the president during the coup led by Gen. Augusto Pinochet on Sep. 11, 1973. (AP Photo/Alberto Bravo)

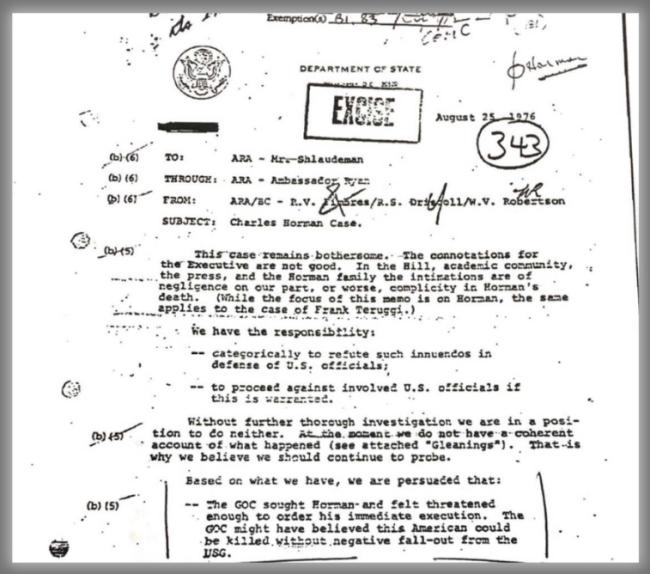

In October 1999, the Clinton administration released a tranche of formerly secret records on the case of Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi, two U.S. citizens executed by the Chilean military following the Sept. 11, 1973, military coup. Part of a larger “Chile Declassification Project” ordered by President Bill Clinton after Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s arrest in London, the Horman-Teruggi papers included some eye-opening documents: One 1972 FBI report on Teruggi implied he was a “subversive” and contained his street address in Chile, and a secret internal State Department report from 1976 on Horman raised the possibility that the CIA might have known the Chilean military had seized him and planned to eliminate him.

“This case remains bothersome,” the memo stated. “In the Hill, academic community, the press, and the Horman family, the intimations are of negligence on our part, or worse, complicity in Horman’s death. …The same applies to the case of Frank Teruggi.”

When those documents were released, they caught the attention of veteran investigative journalist John Dinges. The records became the catalyst for his meticulous effort to revisit the murky history surrounding the Horman and Teruggi executions in his new book, “Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup.” Like Horman and Teruggi, Dinges had traveled to Chile in 1972 to witness Salvador Allende’s unique and promising experiment in electoral socialism; indeed, he knew both men.

“When I embarked on investigating Horman and Teruggi’s cases,” Dinges writes, “I hoped and expected I would put to rest the most critical question: Did the U.S. government participate in or approve the murder of two American citizens by its ally the Chilean military?” With the new documentation, Dinges observed, “I fully expected to prove the hypothesis in the affirmative.”

The ‘Missing’ narrative

That U.S. officials were complicit in the executions of two U.S. citizens in Chile has been an article of faith for the left for almost half a century — in large part because of the powerful, Oscar-winning movie, “Missing.” The 1982 film directed by Costa-Gavras poignantly depicts the protracted search by Horman’s wife, Joyce, and his father, Ed, to locate him after a Chilean military unit disappeared Horman in Santiago. Tracing real events, “Missing” created a compelling narrative that Charles had been targeted because of revealing conversations he and a travel companion had with U.S. military officers on the day of the coup in Viña del Mar, before they were driven back to Santiago by the head of the U.S. Military Group in Chile, a Navy captain named “Ray Tower” in the film — Capt. Ray Davis in real life.

Almost three decades later, this Hollywood narrative received real-life validation when a Chilean judge stunned the world by indicting Davis as an accomplice in the murders. In 2011, Judge Jorge Zepeda charged that Davis knew of the detentions of Horman and Teruggi but did not prevent their deaths “although he was in a position to do so.”

As Dinges explains in his book, Zepeda’s ruling drew heavily on claims made to U.S. journalists in June 1976 by a Chilean intelligence defector named Rafael Gonzalez. At the Italian Embassy, where he and his family had sought asylum to flee Chile, Gonzalez told a CBS News and Washington Post reporter that he had been called to interpret for Horman after he was detained, that there was an American in the room identifiable because of the way he tied his shoes, and that Gonzalez had been told by the head of Chilean military intelligence that “this guy knew too much … Horman … and that he was supposed to disappear.”

The court expediente (case files) on Zepeda’s investigation totaled almost 7,000 pages of testimony and documents. As part of his extensive research for “Chile in Their Hearts,” Dinges meticulously reviewed all the records for the evidence behind Zepeda’s historic ruling. What he found gave him “a shock”: nothing.

“I found no evidence either for general coordination or individual responsibility by U.S. officials in the death of the two Americans,” Dinges summarizes his [non] findings. “By any standard, be it probable cause, preponderance of evidence or simply the journalistic rule of reasonable verification of facts and sources, the case against Captain Ray Davis did not stand up to scrutiny.”

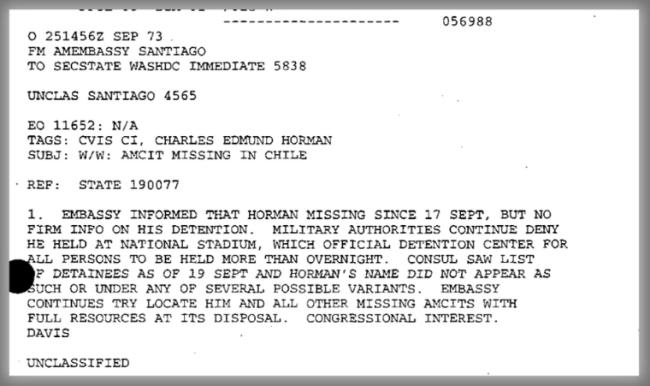

An image of the embassy cable that Chilean Judge Jorge Zepeda misused in his ruling. (National Security Archive)

Zepeda’s ruling stated that “the United States Embassy informed the Department of State about the disappearance of Charles Edmund Horman Lazar — according to declassified document 04565252528Z — at the very moment when the victim was still alive, in custody and being interrogated in the upper floors of the Ministry of Defense.” But Dinges located that embassy cable. It was dated Sept. 25, 1973, eight days after Horman was taken by Chilean soldiers from his home in the factory district of Santiago, and a week after Horman’s unidentified, bullet-riddled body was delivered to the morgue. Far from evidence that embassy personnel knew Horman had been detained while he was still alive, the cable stated clearly that the embassy had “no firm info on his detention.”

“The court,” Dinges concludes, had “misread or misinterpreted the cable and used it incorrectly in an attempt to demonstrate [U.S.] foreknowledge of Horman’s death.”

Moreover, the case files contained a signed affidavit from Gonzalez recanting his story that there had been an American in the room and that Horman had to disappear because “he knew too much.” Gonzalez admitted that the story was “an absolute falsehood,” made up under duress to secure a safe exit from Chile for him, his wife and young son, after being stuck in the Italian Embassy for months. “Gonzalez was able to fool not only the family but journalists, diplomats and U.S. congressional actors with his initial accusations,” Dinges reports. “His story of the man who knew too much and a possible U.S. role drove the Horman case into the highest tiers of public awareness, especially with the success of the Costa-Gavras film ‘Missing.’”

Charles and Frank

As someone who initially believed the premise of “Missing” was “highly probable,” Dinges understands the political sensitivity of his revisionist challenge to the movie’s engrained narrative.

“Why should we relitigate these events that occurred a half-century ago?” he asks. “The short answer is that history deserves the truth. Especially regarding key moments in U.S. government actions that paved the way for anti-Communist dictatorships and changed the lives of millions of people.”

The long answer, however, can be found in the pages of his book. Among its revelations are the identities of Chilean military officers involved in Horman’s detention who were never held legally accountable, the efforts by Chilean officials to “disappear” Horman’s body so their lies about his murder would never be exposed, and the contributions of U.S. officials to abet a protracted cover-up of the Chilean military’s responsibility for these atrocities — and countless others — to protect the nascent regime against condemnation for its rampant human rights crimes.

Indeed, the book presents a comprehensive indictment of how the Horman and Teruggi families were abused by U.S. officials, as they desperately searched for answers and accountability. In a private, personal history written by Ed Horman that Dinges obtained for the book, Charles’ father denounced what he called the “negligence, inactivity, and failure of the American Embassy” to hold the Chilean military accountable for Charles’ murder.

“Far from exonerating the U.S. government,” Dinges argues, “the evidence demonstrates definitively that the U.S. Embassy and State Department shielded the Pinochet regime by hiding the truth, conducting a sham investigation, and sanctioning Chile’s official cover up of the murders.” His book quotes an explanation of this cover-up from a former State Department officer: “the United States government was anxious to see the post-Allende regime prosper.”

But most importantly, “Chile in Their Hearts” tells the untold story of the two Americans, resurrecting Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi as conscientious defenders of Allende’s revolution — portraits of their personal and political journeys that have been missing from previous coverage of their cases. “My investigation was focused on their political associations and actions that might be related to their death. In short: who were these two young men, how were they killed and why,” Dinges writes.

“The United States government was anxious to see the post-Allende regime prosper.”

The book opens with a chapter titled “Charlie and Joyce,” recounting how Horman and his wife met, married and made their way to Chile. A following chapter on “Frank” details his activism in anti-war and solidarity organizations such as the Chicago Area Group on Latin America. We even learn that Teruggi was a volunteer for the NACLA Report on the Americas during his years at University of California at Berkeley.

Teruggi arrived in Santiago in January 1972, and Charles and Joyce arrived a few months later, in June. They overlapped at Fuente de Informacion Norteamericana, described as “a small group of progressive young North Americans drawn to Chile to witness, study and live el proceso chileno,” which translated U.S. articles about Chile and distributed them to key groups in Santiago.

As civil discord escalated, they followed distinct trajectories toward a more militant advocacy and defense of the revolution. Teruggi quickly hooked up with the Frente de Estudiantes Revolucionarios and began working with the Revolutionary Campesino Movement. He befriended leading members of the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR), a militant, Che Guevara-inspired political party that pressured Allende’s socialist-communist coalition to move more aggressively to institute socialism in Chile. Teruggi lived in a well-known MIR safe house, where one of his housemates worked with the MIR Central Committee and another was a member of MIR’s clandestine military wing. Members of the MIR became top targets for elimination by the military.

Horman’s radicalization was less tied to political parties but militant, nonetheless. During his 15 months in Chile, he did some political writing and research and worked on film projects, including one about Allende’s revolution. After an attempted military coup in June 1973, Horman deepened his commitment to workers’ defense of the revolutionary process Allende had started. In July, Horman began assisting pro-Allende construction unions protecting low-income housing projects. In August, he returned to New York for several weeks and approached close friends to raise money for arms to defend the revolution, as Dinges reveals for the first time in his book.

“He asked me for money to help arm the Cordones Industrials [the worker-controlled factory sectors] around Santiago against the threat of a right-wing military coup,” one of those friends recalled. “He said the Cordones were going to be the battleground in the coming conflict. He said arming the Cordones was what was needed.”

The book pays tribute to their courage and radical dedication. “Charlie and Frank were internationalists,” Dinges writes, comparing them to the brigadistas who fought and died to defend Spain from Franco’s fascist forces, “and they are in the noble ranks of so many others who traveled to another country to support and experience a revolution grander than themselves.”

The title of the book, “Chile in Their Hearts,” explicitly draws on that comparison. It derives from the epic poem, “Spain in Our Hearts,” by Pablo Neruda when he served as a diplomat in Madrid in 1936:

You will ask: why does your poetry

not speak to us of sleep, of the leaves,

of the great volcanoes of your native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets,

come and see

the blood in the streets,

come and see the blood

in the streets!

Like Spain, as this book reminds us, Chile became an enduring battleground between the promise of an egalitarian society and the dark evil of fascism. The country remains a leading international symbol — of imperial intervention, repressive authoritarianism and, most importantly for today’s world, the power of citizens to reclaim their nation’s democratic foundation.

“Chile is a great love,” Dinges ultimately concludes, “and what happened there was a great wound in our hearts.”

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.