Congress Scrambles in Wake of Court’s Campaign Finance Ruling

When the Supreme Court handed down its Citizens United v. FEC ruling in January, it did more to sound the alarm on special interest money in politics than any campaign finance reformer could have dreamed.

This article appeared previously on The Huffington Post.

When the United States Supreme Court handed down its Citizens United v. FEC ruling in January, it did more to sound the alarm on special interest money in politics than any campaign finance reformer could have dreamed. The first instinct among legislators in responding is to not make the perfect the enemy of the good. But the question still circulating is: how far will that response go? There is some worry that a quick political gesture could very well supplant meaningful, further-reaching policies to address the role money plays in American elections.

The legislative response to Citizens United will be limited, yet it could lay the groundwork for ushering in a novel approach to campaign finance going forward: one that bypasses the Roberts Court’s favoritism for the wealthy few by activating the lower- and middle-income many. Of course, this will all depend on the Democratic leadership’s endurance on the issue.

Immediately following the Court’s ruling in January, the White House and Democrats in Congress vowed to soften the blow from the decision through whatever means possible. In his weekly radio address, after criticizing the decision during his State of the Union, Barack Obama promised a “forceful response” from his administration. And in a conference call to reporters, Senator Charles Schumer dismally warned that, “if we don’t act quickly, this decision will have an immediate and devastating impact on the 2010 elections.” Now, just three months later, Schumer and Congressman Chris Van Hollen intend to follow through on the promises with the formal introduction of a Citizens United fix bill in the coming days.

Back in February, the two high-ranking Democrats (Schumer is a former DSCC Chairman and the third ranking Democrat in the Senate; and Van Hollen is the current DCCC Chairman) put forward a preliminary itemized plan to address the effects of Citizens United that would withstand judicial reversal by operating within the legal framework established by the Court in its decision. According to Van Hollen spokeswoman Bridgett Frey, the bill was released early on so as to allow ample time “to incorporate feedback and craft strong legislation that responds to the court’s decision.”

The February proposal, which Van Hollen described as a “right-to-know bill” — had six major provisions, which included: banning election expenditures from foreign interests and pay-to-play entities, namely government contractors and TARP recipients; enhancing disclaimers to identify the sponsors of ads; enhancing transparency and the public disclosure of political spending; setting clear and affordable rates for political advertising for candidates, especially TV airtime; and prohibiting corporations from coordinating electioneering activities with a candidate or party.

The final bill is said to be pretty close to that original framework, minus a provision that would require that corporations increase disclosure of political spending to their shareholders (this is to be included in a separate Financial Services bill instead). Congressional spokespeople tell me that the salient concern is having it withstand further Supreme Court challenges. And while it has yet to garner support from across the aisle, polling suggests that it could be a prime candidate for the long lost art of bipartisanship.

The question of whether each element of the bill is susceptible to judicial reversal is a prudent one — and the answer is very much up in the air for some provisions. According to Richard Briffault, Columbia Law School’s Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation and a noted authority on the Court’s history of campaign finance rulings, “the bill seems to go to the limit of what Citizens United left open — foreign corps, pay-to-play, disclaimers and disclosure, coordinated expenditures — without crossing the line…[But] the extension of pay-to-play to independent expenditures probably pushes hardest.”

Briffault has concerns that certain elements could be difficult to hash out in practice, such as determining whether a firm qualifies as “foreign” enough (the bill sets this at 20% foreign owned, but the controlling interest in a public company isn’t always static), or whether it is legal to impose a new TARP restriction on bailout recipients after they’ve already accepted funds under the original conditions. Moreover, extending the pay-to-play ban on contractors and TARP recipients to independent expenditures could prove problematic, since it is precisely this distinction that Citizens United did away with in the first place. Beyond these possible trip-ups, Briffault sees the Schumer-Van Hollen proposal as instituting only very mild extensions of already existing laws.

Other Court followers are even less confident in the proposed bill’s judicial resiliency. For his part, Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig, a leading progressive voice in campaign finance matters, sees almost every provision in the proposed legislation as either ineffective window dressing, or as a prime target for the Court to strike down. He tells me, “I think one could not be too strong about this: It is absurd to suggest this is a ‘fix’ to Citizens United. The bans are plain targets for new lawsuits… All and all — [this bill is] a complete zero. And a strong signal of the failure of the Democrats to deliver on the reform promise of this administration.”Lessig is a staunch proponent of the Durbin-Larson Fair Elections Now Act, and for amending the Constitution to give Congress sole power over campaign finance laws. The Fair Elections Act is essentially the “public option” for electoral fundraising. It was introduced in March 2009 by Democratic Party Whip Richard Durbin and then-Republican Senator Arlen Specter and would provide voluntary public campaign financing to candidates who reach a certain dollar amount through small contributions of $100 or less. Once one opts in, he or she receives funding both for the primary and general elections, as well as a few other perks, such as broadcast advertising subsidies.

In an essay shortly following the Citizens United ruling, Lessig praised the Fair Elections proposal as a means for providing “an immediate balance to the deluge of corporate funding that this next election will now see. More importantly, it will give candidates a way to fight that deluge without themselves becoming even more dependent upon private, special interest funding. No other reform — including reforms that try effectively to reverse Citizens United — could be as important just now. No other reform should distract us from pushing strongly to get Congress to pass this statute now.”

Those crafting the Schumer-Van Hollen bill will tell you that the Fair Elections Act has no chance of making it to the president’s desk at this juncture. Nevertheless, Congressman John Larson, its House-side sponsor and Chairman of the House Democratic caucus, may propose it as an amendment. With 141 co-sponsors in the House, it’s hardly a pipe dream. The problem is in the Senate, where it has but 10 co-sponsors (a list that is noteably lacking Schumer’s name).

It’s not politically unreasonable that the Democratic leadership is proceeding cautiously and in narrow terms. No system is overhauled in a single stroke, and they’re legislating within the parameters of what is admittedly a difficult political environment. The result is that the Schumer-Van Hollen bill will likely be exceedingly limited in its effect on political spending; and most with whom I spoke regard it more as an obligatory political gesture than anything else.

Aside from the necessary need to do something, the Democrats’ bill cannot be expected to make a “radical difference in the mix of resources and politics,” Michael Malbin tells me. Malbin, the Executive Director of the nonpartisan Campaign Finance Institute in Washington, DC, sees the Schumer-Van Hollen bill as good in spirit and worth pushing through to the president’s desk, but, ultimately, as a political necessity with only a few very mild, superficial policy benefits.

At best, the new regulations may theoretically lend slightly more transparency to the paper trail of campaign monies through more disclosure and the Stand By Your Ad provision for CEOs. But even this is seen as wishful thinking by some. In response to stricter disclosure rules, Lessig points to Marcos Chaman and Ethan Kaplan’s Iceberg Theory of Campaign Contributions, which demonstrates that special interests don’t actually need to run election ads when the mere threat of doing so will suffice. As Lessig notes, “those threats are not disclosed.”

This is also an area where Briffault agrees, telling me, “I suppose that some people think that the disclosure and disclaimer requirements … will reduce corporate spending. I doubt that it will. I think the law does as much as the Supreme Court will allow, but for those who think that corporate spending is the problem, this bill won’t and can’t stop that.”

Most other provisions in the bill are said to fall similarly short. According to Lessig, the campaign-corporation coordination ban looks good on paper, but is more or less meaningless in the Internet age. The same can be said for the ban on foreign influence. As Loyola Law School professor and author of the Election Law Blog Rick Hasen tells me, there is a trade off between having the bill withstand judicial challenge, on the one hand, and having it provide truly effective regulation on the other. According to Hasen, “if ‘foreign’ corporation is defined broadly, it will be unconstitutional; if defined narrowly, it won’t do much.”

For many observers, the worst case scenario is that our political leaders will convince themselves that they have adequately addressed what the Court’s ruling in FEC v. Massachusetts Citizens for Life, Inc. (1986) described as the “corrosive and distorting effects of immense aggregations of wealth that are accumulated with the help of the corporate form and that have little or no correlation to the public’s support for the corporation’s political ideas.”

The current political stalemate is quite familiar in the history of the campaign finance debate. The Roberts Court has made it abundantly clear that free speech trumps all else in its rulings. As Briffault wrote in a 2008 Brookings Institution essay, describing the Court’s 2007 ruling in Wisconsin Right to Life v. FEC: “WRTL also abandoned [the] view that in campaign finance cases the Court should reconcile and balance free speech values with other concerns like political integrity, the promotion of democracy, and respect for Congress’s efforts to balance these goals. Instead, Roberts’s opinion framed the case entirely from a First Amendment perspective. It was not about the rules governing the corporate role in financing elections but simply ‘about political speech.'”The foremost misconception — or at least exaggeration — plaguing the Citizens United ruling is that, in the words of President Barack Obama, it “reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests … to spend without limit in our elections.” This gives the decision too much credit. In reality, the floodgates were already open.

During the 2008 Minnesota Senate race between Democratic contender Al Franken and Republican incumbent Norm Coleman, the corporate-funded U.S. Chamber of Commerce ran a television advertisement depicting Franken with duct tape over his mouth. A narrator’s voice came in to say: “High taxes hurt. But it seems like every time Al Franken opens his mouth he talks about raising taxes. This from a guy who was caught not paying his own taxes in 17 states … Maybe he shouldn’t open his mouth … Tell Al Franken that high taxes aren’t very funny.”

This ad ran before Citizens United, and it was on the up-and-up in accordance with the Robert Court’s 2007 WRTL decision because it qualified as “issue advocacy,” rather than “express advocacy” for a specific candidate. Or in other words, the ad was permitted because it did not directly call for a vote for or against Franken. As Lessig has noted, this is the status quo that reversing Citizens United would return us to.

Non-party election communications like the Chamber’s Al Franken ad were generally exempt from regulation for decades, from 2002 back to 1976, when the court created the distinction between “issue” and “express” advocacy in its Buckley v. Valeo decision. During that era, whether or not electioneering communications qualified as “express advocacy” — which was subject to regulation — depended on whether they contained the “magic words,” such as vote for/against or elect/reject.

In 2002, the McCain-Feingold Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act sought to rein in the special interest spending binge of the 1980s and 1990s with a ban on soft money to the parties, and a ban on corporate electioneering communications within 60 days of a general election (both of which are provisions that the Court actually upheld in its 2003 McConnell v. FEC ruling).

However, following John Roberts’ appointment in 2005, and, more importantly, Samuel Alito’s in 2006, the Court transitioned back to narrowing the grounds for regulation and opening the door for independent political spending. In its 2006 Randall v. Sorrell decision the Court struck down Vermont’s attempt to regulate campaign contribution limits. And in WRTL v. FEC the Court did away with McCain-Feingold’s corporate and union electioneering communication provision — thus re-allowing corporations and unions to run “issue advocacy” ads, as long as their only reasonable interpretation wasn’t as an “appeal to vote for or against a candidate.”

When people like the president say that Citizens United opened the “floodgates,” what they mean is that corporations (and unions) no longer have to worry about the “issue advocacy” vs. “express advocacy” distinction. The Chamber of Commerce can now run an ad that says, “Vote for Candidate A,” instead of “Tell Candidate A that high taxes aren’t very funny.”

Whether or not there actually will be a flood of corporate expenditures in the upcoming November election is yet to be seen. For his part, Malbin doesn’t think this will be the case, telling me, “I don’t think most for-profit corporations are likely to increase their public affairs budget because of Citizens United. They will probably just move money around within that already existing budget.” This suggests that some corporations may indeed indulge in the lesser restrictions, but that they won’t break the bank doing so.

With the dual standoff between a deregulatory Court on the one hand (Justice Stevens’ retirement will not alter the liberal-conservative composition of the Court), and a demonstrably obstructionist and anti-regulation Congressional opposition on the other, any promising path forward for the Democratic leadership would seem elusive. Nevertheless, there is a novel approach among serious thinkers across the ideological and political spectrum that is increasingly gaining traction among Members of Congress and the administration. Rather than battling the inexorable stream of political money from the wealthy few, the answer, according to some, may lie in addressing the other side of the equation: the middle- and lower-income “many.”Malbin is one of the experts pushing for this new approach to campaign finance. He looks at the history of Supreme Court rulings on the matter, the failure of restrictive legislative measures to truly stymie the flow of special interest money into elections and politics (there are always ways around restrictive laws, he points out), and the burden on non-wealthy or knowledgeable participants to navigate the sea of complex regulations and concludes that past campaign finance reform efforts have approached the situation from the wrong side.

Along with Anthony Corrado of Colby College, Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution, and Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute-Brookings Election Reform Project, Malbin is the co-author of a paradigm-shifting report published this year — “Reform in an Age of Networked Campaigns” — that advocates “activating the many” instead of “focusing on attempts to further restrict the wealthy few.” The authors put faith in the notion that “if enough people come into the system at the low end there may be less reason to worry about the top.”

A central proposal of the report’s reform recommendations is a public financing option very similar to the Durbin-Larson Fair Elections Act. But there are also other policy measures for incentivizing small-scale donor participation that could garner wider support in the aftermath of Schumer-Van Hollen.

One is to make broadband access affordable to all. Having demonstrated the profound effect of the Internet and social networking on electioneering during the 2008 presidential campaign, this is something the Obama administration is already working on this with its National Broadband Plan. Alongside broadband access is a policy goal nebulously known as “network neutrality,” which advocates the regulation of Internet providers whose service would possibly discriminate against certain political or issue speech that threatens the company’s interests. These efforts suffered a blow recently with a D.C. Circuit Appeals Court ruling that will now limit the FCC’s authority to regulate Web traffic. However, if policy changes are made to reclassify Internet access as a “telecommunications service” instead of an “information service” then the FCC could regain some of its lost authority.

Malbin and his colleagues also call for a central government website to host, “all electorally relevant material about political spending that is required to be disclosed under current law,” and for States and the federal government to provide free software to facilitate electronic disclosure filings that would be made immediately available to the public. Despite hefty corporate and special interest resistance, ideas like these are trudging steadily forward in campaign finance policy discussions. The Schumer-Val Hollen bill does seek to enhance corporate disclosure, but the efficacy of these measures would increase dramatically if this information were to be made more readily accessible to the general public through a central online clearinghouse.

But even if stricter disclosure regulations are accepted to be an effective deterrent, they still don’t do anything “to radically change things one way or the other,” Malbin says. According to Malbin, the only ultimately effective counterbalance to corporate and special interest spending in elections is an expansion of the playing field to include “the many.”

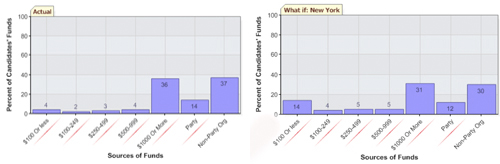

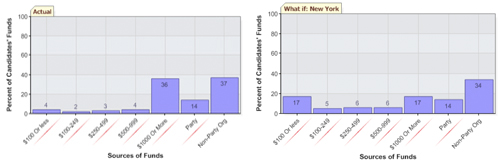

For example, Malbin tells me that in most states it would only take 4 or 5 percent of the electorate giving $50 each to introduce meaningful balance to elections for Governor and the State legislature. He has the numbers to prove it. Policy measures as simple as rebates or tax refunds for low-income donors, individual contributions limits to give small-scale donors more weight against the wealthiest, and publicly funded contribution matching that applies only to small donations have all demonstrated promise for successful implementation. A new interactive tool on the Campaign Finance Institute website puts some to the test. Using data from the 2006 election cycle, with the state of New York as an example, if the government matches small donations ($100 or less) at a rate of 3-to-1, it more than doubles the distribution of contributions from this donor group from 4 percent to 10 percent.

When public contribution matching only for small donations increases to 5-to-1 the percentage of $100 or less funders more than triples, from 4 percent to 14 percent.

And when a 5-to-1 public matching only for small donations is complemented by a $2,000 individual contribution limit, the percentage of $100 or less funders more than quadruples, from 4 percent to 17 percent.

Malbin tells me that these ideas to activate and engage “the many” are beginning to take hold alongside the traditional instinct to just construct more temporary walls. Most campaign finance proposals in the past year and a half — including the Durbin-Larson Fair Elections Act — are looking more towards implementing this approach. However, the Schumer-Van Hollen response to Citizens United does not. It’s far more politically tailored to the immediate outrage since January and intentionally forgoes pushing larger, more reformative measures. For his part, Malbin sees this as an understandable approach, telling me, “I don’t think anybody would look at the Senate right now and think they could get 60 votes to pass [something like] the Fair Elections Act this year.”

Nevertheless, he sees Schumer-Van Hollen — and the likely floor vote on Larson’s Fair Elections amendment especially — as at least a symbolic political gesture. If the Democratic leadership continues forward with corollary efforts — such as for affordable broadband access, network neutrality, and a streamlined electronic disclosure process; and if Members in Congress continue to hone policy proposals and political rhetoric towards incentivizing small donors instead of continuing the endless corporate/special interest regulatory chase, then the future could be brighter than what many cynics would have one believe.

The Internet — and social networking especially — has broken down traditional barriers to accessing information and propounding ideas more thoroughly than any other factor in modern history. The new media elements operative in Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential victory will only matter increasingly more going forward, regardless of whether the Supreme Court continues to open more doors for corporate electioneering. And even in today’s intractable political climate, measures that supplant what is seen as plutocracy with democracy can be sold to both sides of the aisle (as the presence of moderate figures like Specter and retiring centrist Senator Evan Bayh on the Fair Elections sponsor list suggests). The slowly growing consensus among those who are actually in a position to return balance to American elections bodes well for the voice of the “many,” at least in the long run. But they will likely need political diligence and constant reminders to see it through.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.