Democrats Are Ready to Blow Up the Party to Stop Sanders

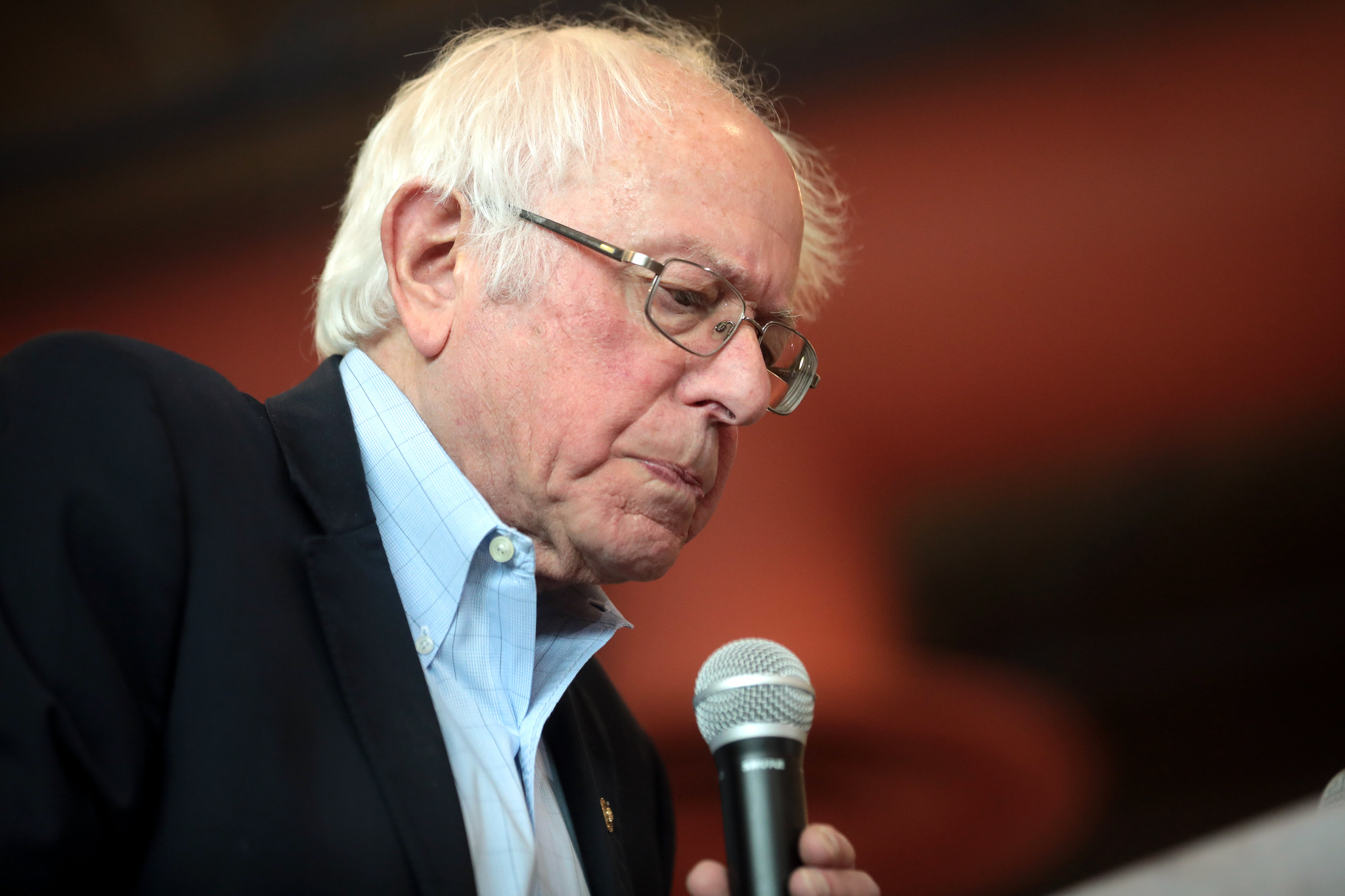

Superdelegates are openly plotting to deny Bernie Sanders the nomination. If they succeed, they risk reelecting Donald Trump and worse. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. (Gage Skidmore / Flickr)

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. (Gage Skidmore / Flickr)

It was a moment that was destined to go viral. During a town hall in Charleston, S.C., on Wednesday, Jason Pietramala, an account manager at a software company and a supporter of Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., posed the following question to Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.: “During the Nevada debate, you and every other candidate on the stage, except for Bernie … indicated that the candidate with the plurality of delegates should not necessarily be the nominee. This essentially means that the will of the voters could be denied by the superdelegates and the DNC, which is basically undemocratic, and in my opinion is a bunch of baba booey to put it politely. Can you explain why the will of the voters should not matter if no candidate reaches a majority of delegates?”

“So you do know that was Bernie’s position in 2016?” she replied, her grin widening when Pietramala answered that he didn’t. “That was his position … that it should not go to the person who had a plurality. And remember, his last play was to superdelegates. So the way I see this is that you write the rules before you know where everybody stands, and then you stick with those rules. Bernie had a big hand in writing these rules. I didn’t write ’em, but Bernie did. … I don’t see how come you get to change [them] just because he now thinks there’s an advantage to him for doing that.”

With a “Hello Somebody” shoutout to @ninaturner, 1 @JasonPietramala asks Elizabeth Warren if she still will go against Bernie being the nominee if he has the most delegates, but not 1991 in Milwaukee?

It got testy, with Warren saying she would take it to the floor. #CNNTownHall pic.twitter.com/gBf1cu0q9m

— Andrew Jerell Jones (@sluggahjells) February 27, 2020

For the Massachusetts senator’s most vocal supporters online, the exchange was cathartic — an opportunity for their candidate to dress down a Howard Stern-quoting “Bernie Bro” in the flesh and for them to temporarily forget she’s finished no higher than third in a caucus or primary. That she was technically correct made it all the more gratifying. Sanders did appeal to superdelegates in 2016 after denouncing them throughout the campaign, even if his primary goal was to extract concessions from Hillary Clinton on the Democratic platform.

Warren is hardly alone in her willingness to deny Sanders the nomination. A New York Times report Thursday finds that in addition to the other presidential hopefuls, dozens of superdelegates are committed to stopping the Vermont senator, even if it means sacrificing the party’s progressive base.

“From California to the Carolinas, and North Dakota to Ohio,” write Lisa Lerer and Reid J. Epstein, “the party leaders say they worry that Mr. Sanders, a democratic socialist with passionate but limited support so far, will lose to President Trump, and drag down moderate House and Senate candidates in swing states with his left-wing agenda of Medicare for all” and free four-year public college. … In a reflection of the establishment’s wariness about Mr. Sanders, only nine of the 93 superdelegates interviewed said that Mr. Sanders should become the nominee purely on the basis of arriving at the convention with a plurality, if he was short of a majority.”

According to the rules set forth by the Democratic National Convention, a candidate can clinch the nomination on the first round of voting by securing 1,991 pledged delegates. If he or she fails to do so, then those delegates become unbound and 771 automatic delegates or “superdelegates” are added to the pool, with each of the latter counting as one half vote. In that scenario, the first candidate to win 2,375 total delegates would become the nominee. What the Times makes clear is that anything less than a clear majority would put a potential Sanders nomination in jeopardy. Some Democrats even appear willing to consider officials who aren’t running in the 2020 race. From the report:

‘If you could get to a convention and pick Sherrod Brown, that would be wonderful, but that’s more like a novel,’ Representative Steve Cohen of Tennessee said. ‘Donald Trump’s presidency is like a horror story, so if you can have a horror story you might as well have a novel.’

Others are urging former President Barack Obama to get involved to broker a truce — either among the four moderate candidates or between the Sanders and establishment wings, according to three people familiar with those conversations.

William Owen, a DNC member from Tennessee, suggested that if Mr. Obama was unwilling, his wife, Michelle, could be nominated as vice president, giving the party a figure they could rally behind.

It’s easy to dismiss Cohen’s and Owen’s suggestions as wish-casting from a small segment of an increasingly desperate and delusional political establishment. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi herself has said that the party will rally behind whoever is nominated, Sanders included. The Vermont senator is the first presidential hopeful in history, Democratic or Republican, to capture the popular vote in his first three contests, and he won the Nevada caucus in convincing fashion. But as Joe Biden’s polling numbers have surged in South Carolina over the last week, so too have the odds that no candidate will win a majority of delegates before the convention in July. Per FiveThirtyEight, that probability currently stands at 50%, the highest of the election cycle.

The dangers of the Democratic Party appointing a candidate who has not earned a clear plurality of delegates are manifold. While it’s difficult to predict precisely how voters might respond, an Emerson poll from January found that just 53% of Sanders supporters would commit to backing another Democrat if he’s not the nominee. That number is likely to plunge if they believe a cadre of unelected officials has deprived him of the nomination.

“It may seem reasonable to suggest a party nominee should have the support of more than half of its members, but in actual practice, the alternative process to determine that nominee is a form of voter disenfranchisement,” argues Shuja Haider in The Outline. “It will be determined not by representative democracy, but by those who already hold power. No wonder people rioted in 1968.”

Then there is the election itself to consider. A brokered candidate all but invites the kinds of cronyism charges that helped depress voter turnout to devastating effect in 2016. Donald Trump would spend the next eight months railing against the party’s corrupt elites, and it’s not hard to foresee those attacks resonating. Moderates will reason that they’d saved the ticket, but evidence that Sanders fares worse than the rest of the field in a general election is inconclusive at best and flatly wrong at worst.

If Democrats succeed in their gambit, they not only risk reelecting Trump but shattering the party. The lone silver lining in that scenario, if it even qualifies as one, is that they will have gotten what they deserved.

This piece has been updated to further clarify the nomination process in the event of a contested convention.

With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.