Eviction on the Installment Plan

Across the country, people and families priced out of the real estate market are turning to temporary housing built to shelter traveling workers. After years spent in extended stays in Colorado and Texas, Gary, an Atlanta native, is currently one of some 25,000 Atlantans living semi-permanently in what was intended to be temporary housing. Photo: Daniel Elkind.

After years spent in extended stays in Colorado and Texas, Gary, an Atlanta native, is currently one of some 25,000 Atlantans living semi-permanently in what was intended to be temporary housing. Photo: Daniel Elkind.

It’s a sweltering late August morning in the parking lot of Comfort Inn, a motel just off Interstate 285 in Sandy Springs, Georgia. The lot sits at the edge of a prosperous northern suburb of the increasingly prosperous city of Atlanta, but there are no signs of this prosperity as I stand chatting with a 40-year-old man I’ll call Gary. A longtime resident of extended stay motels across the South and West, Gary has called them home in Colorado, Texas, Jackson, Mississippi, and two here in Atlanta.

“They’re usually highwayside, basically interchangeable,” he says. We watch as a young woman sitting on a suitcase across the parking lot empties the contents of her purse onto baking asphalt for what seems like the 10th time. “She’s out again,” Gary observes. “She’ll be back, if there’s still a vacancy.” When her ride arrives, the young woman and her bags disappear, leaving behind a rose-colored tube of lip gloss on the curb.

After losing his job at a small Colorado weekly newspaper in 2019, Gary spent two years searching for work around Denver before returning to his native Atlanta. Ever since, he’s been shuttling between the Comfort Inn in Sandy Springs and various InTown Suites, a ubiquitous lodging option that operates under the tagline, “Stay. Save. Smile.” He pays $525 a week, including taxes, or $2,100 a month for a single spare room with a bathroom and — if he’s lucky — a microwave. Some locations are cleaner than others; some feature unwanted roommates, from bedbugs and cockroaches to dripping pipes and mold. In the lobby, the vending machines are stocked with toothpaste, deodorant and school supplies. In Gary’s semi-professional opinion, the Extended Stay America down the street is a classier option, but charges $590 a week.

Prices at motels in competitive locations like these have grown apace with inflation, outrunning Gary’s salary of $45,000 (no benefits) as the web coordinator for a local paper. With no savings or a car of his own, he’s made a home of the Comfort Inn, allowing him to walk to work. He’s explaining how the deposit system works when the receptionist finally appears at the front desk, apologizing profusely, to check him in. We’ve been waiting for her to finish her double duty as part of the housekeeping staff.

After losing his job at a small Colorado weekly newspaper in 2019, Gary spent two years searching for work around Denver before returning to his native Atlanta.

Most people have at least a basic understanding of the factors that have led hundreds of thousands of Americans like Gary to places like this across the country, but especially in the rapidly gentrifying South, which leads the country in housing insecurity. First came an influx of tech workers. Then the hedge funds and private equity firms like the Blackstone Group bought up an outsized portion of available housing options, including single-family homes — accounting for more than 40% of home purchases in metro Atlanta by the end of 2021. Restrictive zoning laws have further aggravated the shortage of new affordable units under construction and ignited fierce competition for what dwindling housing stock remains. The impact is even more pronounced the further south and west you move — Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas lead the housing insecurity index, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research — but Atlanta is unique in hosting one of the highest densities of extended stay hotels in the country. Working families priced out of the housing market in every region have replicated a familiar if tenuous version of stability and routine: Parents begin their morning commute to what may be the first of several jobs, school bus drivers amend their daily routes to pick up students, notebooks and pencils are purchased from a vending machine.

There is little suspense as Gary heads off to his new room. He knows exactly what it will look like before he sees it. Extended stay motels in Denver and Aurora are just like the ones in Atlanta. Even the wall art is often the same, a common through-line, like the ease of finding drugs and of drugs finding you.

There is, however, a special poignancy to Gary’s life here. He is no newcomer or drifter, but grew up nearby, in suburban Dunwoody, where he was obsessed with the hometown Braves and Hawks and Falcons. He can tell you everything about the old Atlanta, from the best now-defunct pizza joints to the wildest old rave spots, most of which have now been demolished to make way for parking lots or condo construction. They say you can never go home again, but these days Gary’s ambitions are more modest than that: he just wants a safe, affordable place to call his own.

“When you live in [extended stay], you’re never really home,” he says. “You’re not homeless, but you’re not home. It’s temporary. And it’s often the best you can do at the time.”

II.

Gary is one of some 25,000 Atlanta residents who have been pushed out into the margins of the rental market in recent years. Originally intended to cater to traveling businesspeople, extended stay motels over the last decade have grown to fill the conspicuous void left by a lack of access to affordable housing — an expensive, private solution to the deepening national housing crisis.

How did things get this way? In his new book, “Red Hot City: Housing, Race, and Exclusion in Twenty-First Century Atlanta,” Georgia State professor Dan Immergluck describes Atlanta as “a preeminent example of both suburban sprawl and twenty-first century gentrification.” He blames not only greedy developers, hedge funds and tech companies, but policymakers and planners at the local and federal levels. The latter, Immergluck argues, “encouraged” Wall Street-backed firms to get into the single-family housing market following the 2008 foreclosure crisis; the former, meanwhile, have done little to remedy fiscal and zoning policies that block the construction of affordable housing, while encouraging corporations and developers to build and profit from commercial properties without generating the very taxes needed to fund affordable housing. The result is skyrocketing land prices and rents, and the displacement of many (often Black) residents.

The problem, according to Immergluck’s analysis, is structural. “Georgia is a strong property-rights state where landlords and mortgage lenders benefit from a legal regime that gives them most of what they want and provides few protections for renters,” he writes in “Red Hot City.” This can take a variety of forms. In 2017, for example, Sandy Springs, where Gary currently lives, “changed its building code to require apartment buildings over three stories or more than 100,000 square feet to be built with concrete construction, raising multifamily construction costs on the order of twenty-five percent or more for such properties.” The predictable result, writes Immergluck, was that “affordable development became almost impossible.”

Gary is one of some 25,000 Atlanta residents who have been pushed out into the margins of the rental market in recent years.

This cozy relationship between officials and real estate capital dictates the direction development takes on the ground and extends to local philanthropic efforts. Influential funders like the Arthur Blank Foundation, for example, tend to prioritize cultural programs over comprehensive economic reform while simultaneously being “closely tied to enterprises that themselves have benefitted from the corporate-friendly policies of the city, including direct tax-payer subsidies.”

Above all, Immergluck counsels readers against succumbing to “‘market-inevitability’ fatalism,” a kind of psychological defense mechanism in the guise of an explanation. Rather than lament the perfect storm of economic plagues, shrugging its policy shoulders and bemoaning the “intractability” of the housing crisis, Immergluck argues, “government is responsible for establishing and regulating many of the institutional structures within which markets operate and so bears a significant share of responsibility for the racialized exclusion and displacement of poor communities.” Now that the effects of this unholy covenant can be palpably felt, if not always seen, all over metro Atlanta and beyond, it may help us to conceptualize the city’s housing precarity and scrutinize solutions more critically.

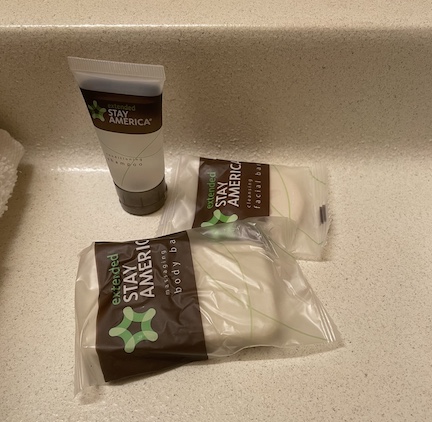

Toiletries are complimentary at the Extended Stay America in Dunwoody.

But at $590 a week for a single room it’s also the more expensive option.

Photo: Dan Elkind.

One effort in this direction involves local startups like PadSplit, which allows single prospective tenants to rent fully furnished rooms in private residences. Like extended stay motels, however, they function without the leases or any of the rights and legal protections usually afforded traditional tenants. This has led to a spate of legal initiatives aimed at addressing the disparity. In August 2021, the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Atlanta Housing Justice League jointly filed an amicus brief in support of a group of tenants at an Efficiency Lodge in DeKalb County, where they attempted to claim basic renters’ protections for long-term residents, many of whom reside for months and years in the same location.

In March 2022, the Georgia Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the tenants. The appeal by Efficiency Lodge will be taken up by the Georgia Supreme Court in November. Arguments are scheduled for next month.

“As a matter of law and a matter of morality, tenants of extended-stay hotels deserve the same rights as other renters in the housing market,” says Miriam Gutman, senior staff attorney for Economic Justice at SPLC. “These are their homes and they have the right to have them protected — providing a source of stable, safe housing for folks who otherwise would be on the street.”

III.

About two months after the scene in the Comfort Inn parking lot, I drove out to Dunwoody to visit Gary at his new place at Extended Stay America. All along I-20, tent villages for those less fortunate than Gary clustered under overpasses, exit ramps, in abandoned lots and empty zones that once belonged to one city authority or another.

Gary had vacated his room at InTown Suites for one at the nearby Extended Stay America because the latter was slightly cheaper and a little more comfortable. They seemed to actually clean the rooms here, he told me, and even left complimentary soaps and shampoos in the bathroom. Plus, it looked out onto the King and Queen towers, one of Sandy Springs’ only landmarks, formally known as Concourse Corporate Center, which reminded him of growing up nearby, and of his late mother.

It now took him 35 minutes to walk to work, but most of the way there was fairly accessible when compared to highwayside extended stays that often lack proper sidewalks or safe shoulders. In January, Sandy Springs announced plans to “realign” the busy intersection of Boylston Drive and Hammond Drive, installing a “side path network” to make it accessible to pedestrians, but has not yet broken ground on the project. In the meantime, mothers with children, elderly tenants and disabled residents at the InTown Suites will have to continue to dodge traffic just to get back to their rooms.

Now in his 40s, Gary is eager to get out of the extended-stay cycle he finds himself in, maybe try to repair his credit and finally fix his teeth, but his rental history and the fact that he’s a recovering addict makes his situation more complicated.

All along I-20, tent villages for those less fortunate than Gary clustered under overpasses, exit ramps, in abandoned lots and empty zones that once belonged to one city authority or another.

“I broke two apartment leasing contracts, for good reasons,” Gary says. “Each time, I got a job offer in a different city or state. And each time, I went to the leasing office and said I’d pay off a chunk of the remaining rent, and each time the leasing office said ‘no.’”

Inevitably, Gary says, he would take the better job offer, leave town and end up breaking the lease. Now, when he fills out a rental application, his forms are immediately flagged because all use the same three credit reporting agencies to screen prospective tenants. Though he’s worked hard to get back on track and now has a “decent-paying job,” Gary is still finding that, in the “City Too Busy to Hate,” his rental history and soaring prices prevent him from getting even a budget apartment within commuting distance.

Although it feels like a personal failure on his end, he also understands that his situation is more or less by urban design. SROs — single room occupancy — and other basic housing options used to be features of big-city life in America, but they were never popular with local officials, police chiefs or property owners who viewed their “transient” residents through a lens of racial and class suspicion. A desire to limit their proliferation has been one of the driving forces behind the unironically named secession or cityhood movements of wealthy northern suburbs like Sandy Springs, Johns Creek, Dunwoody and Brookhaven, which have tended to couch their legal separation from the city of Atlanta in what they perceive to be less politically polarizing terms, such as the deterrence of crime and human trafficking. Politicians advocating for establishing the city of Buckhead claim exclusionary housing laws are necessary in the name of preservation — to protect the “character” of their neighborhoods, the interests of their constituents or simply out of an abundance of fiscal caution.

There are currently two “cityhood” bills in the Georgia legislature that propose the secession of Buckhead, S.B.s 113 and 114, both of which are sponsored by Sen. Randy Robertson, a Republican who hails not from Buckhead but from a district in southern Georgia. Opponents argue that secession would set a bad political precedent and have potentially negative effects on local businesses, without making much of a dent in crime. Though ostensibly more ideologically diverse today, these movements have their pedigree in decades-old Republican divide-and-conquer strategies. No one was surprised, for instance, when the group behind East Cobb’s secession hired two well-known Republican lobbyists, one of whom, Don Bolia, is a former aide to the veteran Georgia Republican, Newt Gingrich.

IV.

In the year-or-so that I’ve known Gary, he often tells me that he feels invisible to other people in his native city. As a renter without a lease, he lacks security not to mention the political weight of actual homeowners and their associations. The media doesn’t help, focusing as it does on the city of Atlanta and ignoring the edges of suburbs where the displaced tend to cluster. The zoning practices undertaken by enclaves like Sandy Springs occur “out of sight” and scrutiny, barely registering in the consciousness of the average metro Atlanta media consumer. It is a cycle that encourages developers, reinforces the status quo and deepens the political and geographical isolation of this growing population.

Gary isn’t exactly resentful or bitter about how things have turned out, but he also doesn’t have many illusions about things changing for the better anytime soon. He says he doesn’t have many options and is anxious about having to find another place to live. As always, he is just one illness or missed paycheck away from losing the roof over his head. There’s no couch to crash on and no car to sleep in.

“No matter what city you’re in,” he says, “life in extended stays can feel like ‘Groundhog Day,’ especially if you’re unemployed. There’s nothing to do and nowhere to go.”

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.