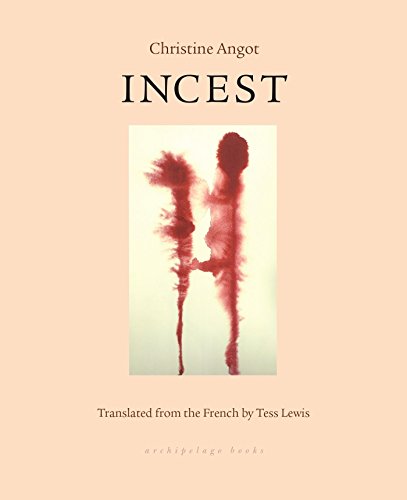

Fearlessly Exploring the Emotional Fallout From Sexual Trauma

A newly translated memoir, "Incest," uses chaotic and explosive prose to show author Christine Angot’s journey through trauma.

“Incest” A book by Christine Angot

French writer Christine Angot’s memoir, “Incest,” is astounding for what it refuses to do. Unlike other recent memoirs on incest that dwell on healing, therapy and even forgiveness, Angot steers clear of this territory and remains embedded in her own maddening struggle for stability. She spends very little time actually discussing her father and the sexual episodes they shared into her late 20s. Instead, she shows us the horrific emotional fallout from this trauma using the chaotic and explosive nature of her prose, which fluctuates between deadening numbness and a hyperactive anger that flirts with madness. This is a brilliant portrait of a brain almost continually on fire with self-loathing. Angot shows us what it feels like to be inside the head of someone mortally wounded. She sees herself as someone who has been contaminated and is now deformed, and she continues to lash out at the world that keeps disappointing her. Her memoir, originally published in France in 1999 and out this month in a new English translation, is both a mesmerizing and harrowing ride.

The book opens with Angot’s description of her new lover, a lesbian doctor whom she has been seeing for the past few months. On the opening page she describes falling in love with her:

I was homosexual for three months. More precisely, for three months, I thought I was condemned to be homosexual. I really had caught it, I wasn’t imagining things. The test results were positive. I’d become attached. Not the first few times. It was the looks she gave. I started on a process, one of collapse. In which I couldn’t recognize myself. It wasn’t my story anymore. It wasn’t me. Still, as soon as I saw her, the test results were the same. I was homosexual the moment I saw her. Things turned back into me afterwards. Whenever she was gone. Other times, even in her presence, I was myself again.”

Their relationship is already floundering. Angot is calling her lover day and night to express her anguish about what her lover has failed to do for her, castigating her for her emotional absence and lack of sensitivity. When the doctor tells her she is going to spend part of the Christmas holiday with her beloved nieces and nephews, Angot berates her for abandoning her and her 6-year-old daughter. When her lover explains that she can’t negate all the people she has loved before Angot entered her life, Angot lashes out at her, oblivious to her lover’s reasoning. Angot can’t reason. She hears only her own heartache. She feels it too. Her joints hurt. Her colitis is flaring. She is having trouble sleeping and she can’t stop reaching for the phone to scream and harass her lover until her lover unplugs the phone. This is another form of death to Angot, who spends the night thinking compulsively about how to get her back.

Angot claims that her only true love in the world is her small child, but that claim is questionable. She speaks to her daughter with a repellent inappropriateness. One night, when the little girl notices the lady doctor has slept over, she asks Angot about her. Angot tells her sharply:

I’m heterosexual. My sweet. Of course. Straight. Or else how could I have had such a pretty little girl? Never, you understand, not once have I ever felt desire for a woman. A man’s sex penetrates radically. I like what’s radical. Other kinds of penetration are possible, borders, journeys. Crossing borders, go get your globe, I’ll explain. …”

We never understand Angot’s defensiveness about her homosexual desire, but we are struck by the insensitivity of her talk with her small child. She’s all force and bravado—uncomfortable with tenderness.

Angot remembers that the one person in her life who did show her tenderness was her Jewish mother, whose surname was Schwartz. Later in life, Angot took her father’s name. She has flashbacks of her mother covering her with a blanket when she was cold, and welcoming her embrace when Angot would hug her closely around the neck. She never clarifies what her mother knew or did not know about her relationship with her father, although there are hints that she was aware of what was happening. But Angot refuses to condemn her mother, while the rest of the world becomes her prey. She is angry, for example, that her lawyer advises her to change the names of the people she is writing about to protect herself legally. She complies, annoyed. She wants to expose those who have hurt her in the past and those who continue to do so. She has no desire to protect anyone. No one has ever protected her.

As her narrative progresses, she seems to almost disintegrate before us on the page. Her punctuation disappears. Her word order becomes more muddled and her sentence structure begins to crumble. It is as though she is drifting away. In one of the book’s saddest passages, addressing her current lover, she writes:

If just once I felt I was born of real love This absence of love turns all my own attempts barren Aborted love aborted fate maybe that’s what it is and maybe that’s my true fate Maybe I’ll never get beyond it Maybe I’ll go from one pair of arms to the next in search of a gesture a face that really speaks to me of love that would address something truly unique to me Single destination of a word that was lost of a love not built of a life that is self-destructing yes I want to belong and I want to love to love you to be loved by you But I’m left with nothing I think of love and I feel invaded I’m afraid of never being able to and if I’m never able to Then what’s the point of continuing Yes I’m afraid and the more I’m afraid the more I keep at a distance from you the more I flee from your face your arms You understand but you can’t stand it and I can’t either I love you.”

We hear startling glimmers in her fractured prose of recognition regarding her trauma. And yet she has still not really revealed it to the reader. Angot has left the revelation of her father for last, as if she needed time to gather her courage, to think about what he made her do. And how he made her feel. And how it has formed her.

We learn less about her father than we would like to, but enough to understand her ongoing agony. He has Alzheimer’s now—something she takes a perverse pleasure in. She remembers him in flashbacks, the same way she remembers her mother. She seems to have trouble dwelling too long on either of them. She recalls the first long kiss he placed unexpectedly on her mouth, and the progression of sexual adventures that followed. He left her mother and married again. He had two other children who did not know about Angot until much later on. When she was in her late 20s, they would meet for vacations together. He was an intellectual man fluent in many languages. He was writing a book on linguistics. He loved reading Le Monde and could not get through a day without it. He suffered from migraines, which she tended to by stroking his forehead in a dark room. When she felt ill, however, he would ignore her. He was never tender with her. She claims she never felt any desire for him, but felt guilty when she experienced pleasure from some of their escapades. He forced her to eat clementines off his genitals, and forced her to have anal sex. He coerced her into performing oral sex on him in a church pew, and because he did not want to ejaculate in church, she had to finish him off in their car afterward.

Angot lived a double life. In high school she would tell her friends about her cultured father and how genteel he was, leaving out the part that ravaged her. She became accustomed to living in traumatized secrecy. Her father often told her she was beautiful and intelligent and had very soft skin, and would have many lovers in her future due to her rare beauty. But he would often castigate her for her lack of manners and sophistication.

Angot is 58 today. She has been writing novels since she was 25. This memoir—technically in the category of “autofiction”—brought her literary accolades and criticism when it came out in 1999 in France. Some thought she had gone too far and revealed things that should remain private. They attacked her for being grandiose and narcissistic. Others felt her book was a brilliant and fearless exploration of a difficult topic.

I believe Angot has done something truly spectacular here. How many of us have had moments in our lives, episodes of vulnerability and sadness, in which we felt compelled to behave in a way that went against our own best interests? How many of us have simply not been able to stop? How many among us have been rejected in love and found ourselves begging and shaming ourselves in ways we could never have imagined? How many of us have been lost in darkness and unable to think our way out of it? Angot’s life is lived in that state—a state of perpetual chaos and dejection. And she has used her brazen, fierce intelligence to translate this reality to the page in a way that reveals her brilliance as a writer and her sadness as a human being. Her journey is one you will never forget.

Your support is crucial…With an uncertain future and a new administration casting doubt on press freedoms, the danger is clear: The truth is at risk.

Now is the time to give. Your tax-deductible support allows us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes what’s really happening — without compromise.

Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and unearth untold stories.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.