Female Reproductive Exploitation Comes Home

Gendered violence is practiced on a widespread scale across the country and occurs in ways many Americans might not realize, even under their own roofs.

Animal rights activists have decried the conditions in which chickens are kept at egg farms. (Robert F. Bukaty / AP)

Sexual violation and reproductive exploitation happen to vulnerable bodies.

After studying systems of female reproductive servitude and visiting “parlors,” exhibitions and auctions where females are sold into captivity, Dr. Kathryn Gillespie of the University of Washington found relentless “sexually violent commodification of the female body.”

Meet Carly (not her real name). Carly was torn from her mother shortly after birth, and while her umbilical cord hung from her, was auctioned off. She lived a life of physical and social isolation until her captors felt she was sexually mature. She was immobilized by chains or with a specially designed containment device, and impregnated with an insemination gun that was forcibly inserted into her uterus.

After nine months, Carly gave birth and bent to caress her child. Once her milk came in (within 24 hours), her baby was taken from her. Sometimes, the children are removed within fifteen minutes of birth.

Had they not been parted, Carly would have suckled her infant for at least six months. After their forced separation, Carly called for her baby for at least two weeks, looked for her and cried for her.

Carly is a cow used in the dairy industry.

Author pattrice jones, co-founder of VINE Sanctuary, explains what typically happens next: Cows like Carly are “hooked up to a machine that simulates sucking and is so rough in doing so that most [cows] develop abrasions and mastitis.” Mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissue, forming painful pockets of pus around the teats.

Several times daily, cows are taken to a milking “parlor.” Today’s cows used in the dairy industry produce 61 percent more milk than cows from only 25 years ago, due to genetic engineering, feed rations and growth hormones. Their udders must carry an extra 58 pounds of milk. But it is profitable weight for the farmer who owns them and sells the products of their bodies.

After being pushed through this regimen, Carly’s bloated udders may force her hind legs apart, causing lameness. Within a few months, she is again restrained and forcibly impregnated. During the first seven months of her next pregnancy, machines continue to take her milk from her. The physical demands of both lactation and pregnancy under these conditions have been compared to jogging six hours a day.

Again, Carly gives birth; again, the baby is taken away. Again, she is hooked up to a milking machine. After three or four cycles of forced pregnancy and continuous lactation, her body, depleted of minerals, is sold, though she may be barely able to walk into the ring at the auction house. Her udders are so distended through overuse they drag on the ground. She gently kicks at her udder with her back legs so that she can walk. Someone then purchases Carly’s body to make ground beef.

Now meet Henny Penny. Her relatives love to sit in trees, form close relationships with others, dust bathe for at least 30 minutes a day and forage for a majority of the day. Henny began calling out to her mother while still an embryo in an egg, but her mother wasn’t there to cluck back or gently turn the egg. After Henny was born, her beak, filled with nerve endings, was sheared off with a hot blade. After four to five months, she was moved to a battery farm and installed with four to nine other hens in a cage no bigger than 18 by 20 inches.

Once there, she is psychologically frustrated because she cannot build or sit on a nest. Nor can she cluck to her embryos, move to a perch, forage, preen, scratch, turn around, stretch her wings, dust bathe, or—because of her deformed beak—eat and drink properly.

“Hens used by the egg industry lead lives of unimaginable misery,” says journalist Mark Hawthorne. “There is absolutely no relief from being crammed into a cage with other birds such that none of them can even spread their wings and [get] no relief from standing on wire day and night. Their muscles atrophy, their skin is rubbed raw, and they never receive medical attention—the industry considers that a waste of money.” He wrote about rescuing hens from battery cages in his book “Bleating Hearts”: “I opened tiny wire prisons to remove birds almost completely denuded of feathers. They seemed so incredibly fragile: all that remained of their wings were a few pitiful quills protruding from the bone. Instead of plumage, these White Leghorns were covered with swaths of red-raw skin. The combs that crowned their heads were flaccid and pale pink, rather than the brilliant rose hue they would regain, along with their feathers, after time in a loving home.”Though birds can grasp abstract concepts and are now considered “feathered apes” in terms of cognitive processing, Henny is viewed as stupid. For the next year or so, the intense ammonia fumes from the vast pool of urine and feces inside the battery shed will sting her eyes and burn her lungs. Urine and feces from hens in the battery cages stacked above hers rain down on her continually. Her cage-mates die and remain in the cage, mummified and trampled underfoot. She lives under artificial light at least 17 hours a day. According to Dr. Karen Davis, author and founder of a poultry sanctuary, the lights mimic “the longest days of summer since it is the length of daylight that stimulates a hen’s reproductive system to form and lay eggs.”

Henny’s eggs roll down the sloping wire floor of the battery cage for easy collection by the farmer. Hens used for their eggs in commercial operations lay an average of 276 eggs a year.

After about 75 weeks, Henny’s reproductive system begins to wear out. She may be starved for up to two weeks—a common trick used to stress hens’ bodies into more weeks of egg production. When her egg production returns, she will produce “jumbo” eggs, causing uterine prolapse. Calcium deficiencies create deformities in her feet, as does standing on wire 24 hours a day. Her uterus, from overuse, protrudes out of her body. Between 75 and 110 weeks of age, a hand grabs her out of the battery cage. Her cage-mates are snatched as well. Because their bodies are so depleted, the hens are considered worthless to the meat industry. Most are suffocated, gassed or buried alive in landfills. Some will be trucked to slaughterhouses and used in low-grade meat products such as pet food.

This is the female torture, violence and exploitation that is almost certainly supported by and normalized within most households.

The same myths that for years defended sexual violence against human women continue to defend the sexual violation and reproductive coercion in the production—and consumption—of cows’ milk and chickens’ eggs.

Myth #1, Used when speaking about sexual violence victims: She liked it. As applied to nonhuman victims: “She needs us to take her milk” and “Only happy hens lay eggs.” pattrice jones explains, “Cows are mammals just like us, and just like us, they don’t produce milk unless they have recently given birth and are nursing.”

In her 2012 book “Chicken,” scholar Annie Potts points out that “hens lay whether they are happy or not.”

Myth #2: She needs us to protect her from violence by others. This is the paternalistic view that women, not men, need curfews. On the farm, this myth becomes the cow or chicken is safer under our control in industrial situations than in the barnyard, where she can be attacked by a bull or a rooster. In fact, the non-human female is often able to refuse sexual advances. jones explains, “If a male cow mounts her and she doesn’t want to be mounted, all she has to do is walk forward, and he falls down. If she does want to be mounted, she positions herself to make it easier.” However, cows cannot walk away from their imprisonment in the animal agriculture industry.

Of chickens, Karen Davis says, “She is not at the mercy of roosters the same as she is with humans. With humans, chickens will try to fight, or go limp, knowing they are in the hands of a power they can’t resist. But with roosters, they know each other’s signals through their evolutionary genetic knowledge. Roosters do not jump on them constantly. Hens signal roosters and communicate through body language, run away, or circle around them, in ways that say they don’t want to mate right now.”

And importantly, they aren’t protected now. A hen who would normally lay two clutches of about 12 eggs a year in the spring and in the summer has been genetically manipulated to produce 270 or more eggs per year. A cow in the dairy industry is “producing” ten times more milk than her calf would ever need.

A cow’s or chicken’s experience of violation matters to her. It is the fact of her existence. We cannot know what they know, but we can know what they feel and experience: discomfort, pain, fear, grief, exhaustion, prolapsed uteri, broken and damaged bones. As Davis describes the hen’s life: “Her body is basically being assaulted, against her will, without her consent and she cannot fight back, cannot defend herself. She is living just as intimately within her body, just as any woman is living intimately within her body and experiencing whatever is done to her body against her will.”

Myth #3: It’s not sexual violence. Of cows, jones says, “Whatever word you use for this, it’s forced penetration by a foreign object of an immobilized female, and at least part of the purpose is an expression of power and control.”Animal agriculture denies that this treatment of cows and chickens is even sex. Gillespie observes:

There is all this work to obscure the fact that it is not sexualized violence, not violence, not sex, yet looking at the [bull] semen industry, a lot of their advertising materials—the t-shirts, boxer shorts, mugs, and other paraphernalia they sell—reveal through humorous puns and jokes about the process that it is an act of sex, it is an act of sexual violence. They match up with the discourses about human women, too.

A graphic for Universal Semen Sales pictures a grinning cartoon bull, two lipsticked cows in the background spreading their hind legs and presenting their backsides, and the slogan, “We Stand Behind Every Cow We Service.”

Myth #4: The home is a haven and the farm is a peaceful place. We know the home is a very unsafe place for marital rape victims, incest victims and domestic violence victims. Nor is the farm necessarily a peaceful place: frightened, abused and physically overused animals live and die there. Yet empathy is often reserved for the abuser: the rapist (“whose promising life is now cut short”) or the farmer (“who is struggling to make a living”). The throwaway victim is epitomized in the cow and the chicken.

Dr. Gillespie described a cow she saw at an auction as so lame that she collapsed, her legs splayed out behind her. Unable to stand, her huge udders were crushed beneath the weight of her body. She was leaking blood and milk. For hours, she lay there. Her back legs were tied together to see if she could stand up. But she could not and at the end of the day, she was shot.

The myths listed above not only allow female exploitation in the dairy and egg industries; they also naturalize sexual objectification and violence against women, who themselves are referred to in certain circles as “cows” or “chicks.” A state legislator in Georgia compared a woman needing a late-term abortion to a cow giving birth to a dead calf. The bill he was supporting became known as the “women as livestock” bill.

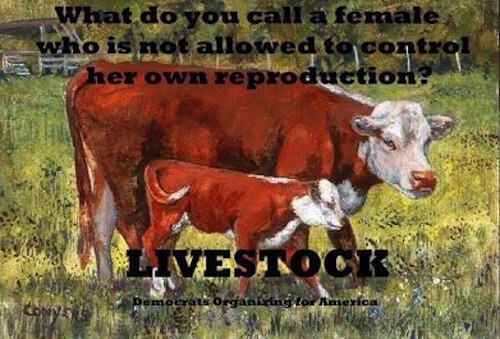

In response to this and other abortion restrictions being introduced in various state legislatures, Democrats Organizing for America released this meme:

Some animal rights activists mistook it for a pro-animal statement. The image used the commodified bodies of female cows and the reproductive slavery they endure to communicate something about the precarious nature of women’s reproductive rights. All the same, there was no understanding that condoning female exploitation in the production of milk and eggs might actually influence attitudes toward women.

When a vet school sells a T-shirt that says, “The Hardest Part is Getting In,” showing a man’s arm elbow-deep in a cow’s vagina, they are talking about more than forced artificial insemination. Pharmaceutical companies sell their products with images of sexy chickens who desire to be consumed and cows who need to stay pregnant. They, too, are talking on several levels at the same time: The idea of women’s bodies as sexually consumable and available for pregnancy are evoked by these images.

As long as we do not examine the products of female torture and servitude that we consume every day and feed to others, we are likely to leave unexamined the ways that gender oppression is intensified and justified by the treatment of these powerless and exploited females. We will continue to support an institution that teaches objectification, distance from the victim and violence in service to personal desires—and are not these also the attitudes that contribute to sexual violence against women?

Carol J. Adams is the author of “The Sexual Politics of Meat,” which has been translated into numerous languages and is now available in a 25th anniversary edition from Bloomsbury. This fall, “The Carol J. Adams Reader” was published. www.caroljadams.com

As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.