A Footnote Looms Large in the Second Amendment’s Future

The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who upended prior interpretations of the amendment, left a tantalizing loophole for advocates of gun regulation. A man demonstrates for First and Second Amendment rights at a 2010 "Restore the Constitution" rally in Arlington, Va. (Toby Jorrin / AP)

A man demonstrates for First and Second Amendment rights at a 2010 "Restore the Constitution" rally in Arlington, Va. (Toby Jorrin / AP)

No one in American history is more responsible for elevating the Second Amendment to the status of holy writ than the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016. His impact is still being felt today in nearly every important gun-rights lawsuit pending from sea to shining sea.

The conservative firebrand’s 2008 majority opinion in the court’s 5-4 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller stood the prior judicial consensus on the Second Amendment on its head, holding for the first time that the amendment protects an individual right to bear arms. Prior to Heller, the great weight of scholarship and court opinions, including the Supreme Court’s 1939 decision in United States v. Miller, had construed the amendment, in keeping with the actual debates of the founding era, as protecting gun ownership only in connection with service in long-since antiquated state militias.

Two years later, in another 5-4 decision—McDonald v. Chicago—the Supreme Court extended Heller, ruling that the individual right to bear arms was incorporated by the 14th Amendment’s due process clause and hence was applicable to the states and local governments. The Second Amendment, as interpreted by Scalia, thus became the law of the land.

In the aftermath of Heller and McDonald, gun-rights advocates, from the National Rifle Association to the Second Amendment Foundation, rejoiced. Having funded and provided the lawyers for both cases, they were confident that many other gun-control measures across the country would soon be toppled, or at least severely curtailed, through subsequent litigation.

But they were wrong—ironically, as I will explain shortly, in no small measure because of a cryptic footnote Scalia added to his Heller opinion.

Both Heller and McDonald were perfect test cases for the NRA and its allies because they dealt with cities—Washington, D.C., and Chicago—that had enacted near-total bans on the ownership of handguns, even when kept in the home. If any cases had the potential to overturn the prior consensus on the reading of the Second Amendment, Heller and McDonald headed the list.

Gun regulations in other jurisdictions, however, were and remain far less stringent. Indeed, the vast majority of U.S. state constitutions protect some form of gun ownership. According to an NRA survey, only New York, California, Maryland, New Jersey, Iowa and Minnesota have no “right to keep and bear arms” provisions in their state charters. Still, even in those six states, state statutory law permits and regulates gun ownership.

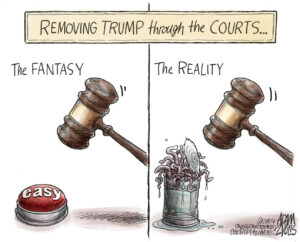

As a result, following Heller and McDonald, most state and lower federal courts, with a few exceptions, have upheld state and local regulations on gun ownership that stop short of establishing complete bans, distinguishing such regulations from the total bans that were nixed in Heller and McDonald.

Most notably, over the past two years, three federal circuit courts—the 4th, sitting in Maryland; the 2nd, sitting in New York; and the 9th, sitting in California—have upheld restrictions, respectively, on personal ownership of AR-15s and other military-style weapons, local gun permit regulations, and the right to carry handguns outside of the home.

The reason courts have been able to hand down pro-gun control rulings is simple: Contrary to popular beliefs—fueled in large part by NRA propaganda mouthed by zealots like Wayne LaPierre, Rush Limbaugh, radio host Alex Jones and so many others—Heller by no means closed the door to constitutionally permissible gun control. In fact, and very much to the contrary, Scalia’s Heller opinion left the door quite ajar.

Toward the conclusion of his Heller opinion, Scalia wrote:

Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. … Although we do not undertake an exhaustive historical analysis today of the full scope of the Second Amendment, nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms. 26

In footnote 26 of the opinion, placed at the end of the paragraph, he added:

“We identify these presumptively lawful regulatory measures only as examples; our list does not purport to be exhaustive.”

As I reported in a 2015 cover story for California Lawyer Magazine, I have interviewed some of the nation’s most prominent Second Amendment lawyers and political historians at length about the Heller case. Almost without exception, they told me not only that footnote 26 is one of the most critical footnotes in the annals of the Supreme Court, but also that, legally speaking, it holds the key to the future of the Second Amendment.

“Post-Heller,” the NRA’s leading attorney in California told me at the time, “the race [is] on to clarify exactly what Scalia meant” in footnote 26.

Since Heller and McDonald, however, the Supreme Court has been reluctant to take up the challenge, although it has adjudicated a few narrowly focused gun cases. In 2014, for example, the court upheld a Virginia ban on “straw” purchases—the practice of buying of guns for those who may be prohibited from making direct purchases themselves. And in 2016, in a case from Maine, the court held that a domestic assault qualifies as a crime that prohibits convicted felons from possessing firearms under current federal law.

Still, the court hasn’t attempted to fill in the blanks left by Scalia’s footnote 26 in any comprehensive way.

When and if it does, it will have to address such weighty matters as whether the Second Amendment applies to the ownership of military-style weapons of war, such as AR-15s, or simply extends to less lethal weapons possessed for self-defense in the home. If assault weapons are found to be beyond the amendment’s purview, then state and local prohibitions against owning them likely will be upheld.

Also on the table will be the more esoteric but nonetheless crucial question about what kind of constitutional test, or “scrutiny,” in the language of legal scholars, should apply to gun-rights challenges. If the court employs “strict scrutiny”—the most exacting test it uses when constitutional rights are involved—many gun-control measures will be ruled invalid. On the other hand, if the court applies “intermediate scrutiny,” a lower standard, most measures will likely be upheld.

Last June, the court declined to hear the NRA-backed petition in the 9th Circuit case from California cited above that raised the issue of whether the Second Amendment protects the right to carry a handgun outside the home. However, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch—Scalia’s successor on the bench and by all indications even more right-wing than Scalia in his salad days—dissented. They urged the court to hear the case.

Writing for himself and Gorsuch, Thomas scolded his colleagues, saying that even if they thought the petition would fail on the merits, denial of review in the case “reflects a distressing trend: the treatment of the Second Amendment as a disfavored right.”

Had Gorsuch never been elevated to the court, it might be possible to dream of a future lawsuit that could lead the court to reevaluate Heller in its entirety. With Gorsuch in place, those dreams have vanished, at least for the near term. The best practical short-term legal strategy for gun-control advocates, therefore, is to urge the Supreme Court to maintain its current narrow approach to the Second Amendment.

The great danger is that with the aging of the court—four of its current members are over 79—and with President Trump wielding the power to nominate future justices, the Thomas and Gorsuch wing eventually will be able to forge a new and even more virulently pro-gun majority. If they do, they may well deliver an answer to the riddle left by Scalia’s footnote 26 that will lead to still easier access to weapons of war and even more mass carnage in our schools and streets.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.