The Future of Partisan Gerrymandering Hinges on Supreme Court Case

The legal decision of Gill v. Whitford will either extend or destroy the legacy of Earl Warren on reapportionment. A portrait of Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry at the Statehouse in Boston. In 1812, the practice of gerrymandering was named in part for Gerry after he signed a bill to redraw a Massachusetts Senate district map. (Elise Amendola / AP)

A portrait of Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry at the Statehouse in Boston. In 1812, the practice of gerrymandering was named in part for Gerry after he signed a bill to redraw a Massachusetts Senate district map. (Elise Amendola / AP)

In a televised interview with the McClatchy News Service on June 25, 1969, Earl Warren, the legendary 14th chief justice of the United States, was asked to single out the most important case of his tenure on the bench, which began in 1953.

Warren, who had retired from the high tribunal just two days earlier, could have named any number of high-profile rulings: Brown v. Board of Education, which ended legal segregation in public schools; Miranda v. Arizona, which mandated that criminal suspects undergoing police interrogation be advised of their rights to counsel and against self-incrimination; Loving v. Virginia, which ended state prohibitions against interracial marriage, to list just three of the many possibilities.

Instead of these or other better-known landmarks of American constitutional law, Warren cited Baker v. Carr, the court’s 1962 ruling on reapportionment, redistricting and gerrymandering that established the doctrine of “one man, one vote”—the principle, as elaborated in subsequent decisions from the early 1960s, that state and congressional electoral districts (whether rural or urban) must be roughly equal in population to ensure that individual voters have an equal voice in selecting their representatives. In so ruling, Warren and a majority of his colleagues held that redistricting claims were subject to judicial review under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. In the process, they overturned long-standing legal precedent that had held redistricting was a “political question” beyond the jurisdiction of the courts.

As Warren explained the significance of the principle to McClatchy: “If everyone in this country has an opportunity to participate in his government on equal terms with everyone else, and can share in electing representatives who will be truly representative of the entire community and not some special interest, then most of the problems that we are confronted with would be solved through the political process rather than through the courts.”

In addition to outlawing straightforward geographic gerrymandering, the Supreme Court has also proscribed “racial gerrymandering”—the practice of purposely designing electoral districts to dilute the voting power of minorities by either “cracking” or spreading minority voters across a state to diminish their relative strength, or by “packing” minorities into a few concentrated districts to drain their influence in other parts of the state.

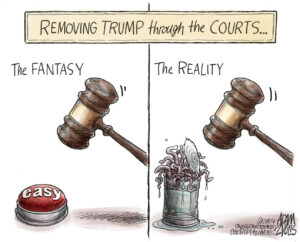

Still, as decisive as the many geographic and racial reapportionment rulings of the Supreme Court since Baker have been, the court has waffled on the equally critical issue of partisan gerrymandering—the act of mapping electoral districts so as to entrench the majority political party in power. Indeed, the Supreme Court to this date has never overturned a state electoral map on grounds of partisan overreach.

In a series of cases over the past 30 years, the court has grappled with two vexing issues in this context: First, whether the judiciary should steer clear of the question of partisan gerrymandering (a portmanteau coined after salamander-like voting districts created by Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry in 1812 to give an advantage to his Democratic-Republican Party), and leave partisan decisions in the hands of state legislatures. And second, assuming that there is jurisdiction, whether there are any manageable objective standards, short of requiring proportional representation (which the court has consistently rejected), that could enable judges to determine when partisan gerrymandering becomes so extreme that it is unconstitutional.

In Davis v. Bandemer, a case from Indiana, the court held in 1986 that judges may review claims of impermissible partisan gerrymandering, although it failed to find one existed in the Indiana scheme challenged in the case.

However, in 2004, in Vieth v. Jubelirer, a case from Pennsylvania, a plurality of four justices (one vote shy of a majority) purported to overrule Bandemer. The plurality opinion, written by Justice Antonin Scalia and joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, held that partisan gerrymanders are never subject to judicial review.

The Supreme Court will revisit both questions this term when it considers the case of Gill v. Whitford, a partisan gerrymandering challenge from Wisconsin. Set for oral argument Oct. 3, the case was brought in 2015 by a dozen Wisconsin Democrats who alleged that the redistricting plan enacted by the state Legislature in 2011 after the last census is unconstitutional because it systematically diminishes the voting strength of Democratic voters statewide.

In support of their claim, the plaintiffs marshaled a bevy of compelling statistics before a district-court panel of three federal judges who heard the case: In the 2012 election, the Republican Party received 48.6 percent of the two-party statewide vote share for Wisconsin General Assembly candidates but won 60 of the 99 seats in the legislative body. In the 2014 election, the Republican Party received 52 percent of the two-party statewide vote share and 63 Assembly seats.

The plaintiffs argued that such disparities not only diluted their voting power in violation of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection, but that it also undermined their First Amendment rights as it subjected them to disfavored treatment because of their political views.

By a 2-1 vote, the district court panel agreed and invalidated the Wisconsin General Assembly map. To reach its determination that an impermissible partisan gerrymander had occurred and to provide the long-sought objective measure of extreme partisanship, the panel relied on a new and wonky mathematical formula for calculating voting asymmetry between the two major parties, called the Efficiency Gap (EG).

Devised by University of Chicago law professor Nick Stephanopoulos and researcher Eric McGhee, the EG applies to both state and congressional races and is nonpartisan in nature. As explained by an Associated Press study, EG theory compares the statewide share of the vote a party receives in each district with the statewide percentage of the seats it wins. It then measures “wasted votes,” which it defines as all those cast for a losing candidate as well as those cast for the winner above 50 percent.

When the two parties waste votes at an identical rate, a redistricting plan’s EG is zero. According to EG theory, a state-legislative plan with an EG of 7 percent or more is presumptively unfair, resulting in overrepresentation of the majority party. A congressional redistricting plan with an EG of more than two seats is considered suspect. The district-court panel in Gill found that the EG in the 2012 Wisconsin assembly race was 13 percent in favor of Republicans and that the EG in 2014 was 10 percent in favor of the GOP, well over the operative thresholds.

The importance of EG theory for the future of major-party politics in America cannot be overstated. According to the Brennan Center for Justice: “In the 26 states that account for 85 percent of congressional districts, Republicans derive a net benefit of at least 16-17 states in the current Congress from partisan bias. This advantage represents a significant portion of the 24 seats Democrats would need to pick up to regain control of the U.S. House of Representatives in 2018.”

The AP study concluded that a similar, distorted electoral landscape has taken shape for state races, not only in Wisconsin but also in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Florida, Virginia and elsewhere.

Could Gill v. Whitford provide the approach to partisan gerrymandering that the Supreme Court has sought? Many observers, including Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the 84-year-old doyen of the court’s four-person Democratic minority, consider Gill the most important case of the tribunal’s upcoming term, even ranking above the Trump Muslim travel ban appeal the court will also review in October.

But while Gill’s blockbuster potential is undeniable, it is doubtful that the current court—with Neil Gorsuch, rather than Merrick Garland, filling the vacancy created by Scalia’s death in February 2016—will produce an opinion favorable to Democrats. Like Scalia, Gorsuch is a committed “originalist” in judicial philosophy, and that bodes ill for acceptance of EG theory.

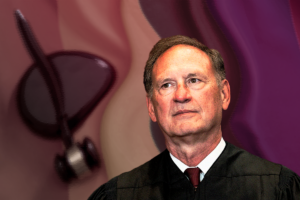

Scalia’s plurality opinion in the Vieth case was a paean to originalism and the view that partisan gerrymandering is off-limits to the courts, regardless of the mathematical standards used to identify and quantify it. Justice Thomas signed on to that opinion. And just last term, in a racial gerrymandering case from North Carolina (Cooper v. Harris), Justice Samuel Alito authored a dissenting opinion, joined by Chief Justice Roberts as well as Justice Anthony Kennedy, which asserted that unlike the racial variety, purely political gerrymandering is a “traditional domain of state [legislative] authority.”

Although Kennedy has also taken the position in the past that political gerrymandering could be a proper subject of judicial scrutiny if sufficiently blatant, he voted in June, along with Alito, Thomas, Roberts and Gorsuch, to stay the district court’s ruling in Gill pending full review of the case.

That review is about to take place. How the court ultimately rules will determine whether the legacy of Earl Warren on reapportionment will be honored and extended or brought crashing to an unceremonious close.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.