Has Iraq Become Another ‘Lesson Lost’ Like Vietnam?

The Army has delayed the release of a 1,300-page internal war study. Some fear it's unwilling to accept responsibility for its failures. The U.S. Army / Flickr

The U.S. Army / Flickr

This piece originally appeared on The American Conservative.

According to reports, the Army has delayed the publication of a 1,300-page internal Iraq war study commissioned by General Ray Odierno in 2013. The volume, which few in the public were even aware of, was an admirable project. After all, the U.S. military famously ignored and jettisoned any lessons after its defeat in Vietnam. Most of us would agree that simply can’t happen again.

So why the delay? Some fear the Army might be hesitant to publish a study that takes its leadership to task for decisions critical to the execution, and perhaps outcome, of the war. (Basically, while the Army says it wants to learn its lessons, it doesn’t necessarily want to see them in black and white.) One chief Army historian claimed it would “air” too much institutional “dirty laundry.”

Indeed, retired Colonel Frank Sobchack, a study team director, expressed concern about the delay in the report’s release, asserting “that the Army was paralyzed with apprehension for the past two years over publishing it leaves me disappointed with the institution to which I dedicated my adult life.”

Of course, there has been skepticism about the report itself, given the commissioner of the project and the composition of the study team. Some fear the conclusions will skew towards a one-sided lionization of the 2007 “surge”—which General Odierno and his closest subordinates oversaw. In fact, reporting in The Wall Street Journal suggests that the report credits Odierno and General Petraeus, who commanded all U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq at the time, for turning the war around by shifting to a theater-wide counterinsurgency strategy (COIN).

These are all legitimate concerns. Indeed, this author has long sought to debunk the flawed notion that Petraeus’s famed “surge” achieved anything more than a temporary pause in violence and political instability. Still, the real problem with this report is that it completely ignores the utterly flawed grand strategy that brought the U.S. military into Iraq in the first place in favor of focusing on more minor tactical mistakes.

Let us review, then, some of the reported conclusions in the study and how they’re disjointed from the larger, strategic failures inherent to the entire American military adventure in Iraq.

The report admits to the following shortfalls:

- More troops were needed to occupy the country and fight an expansive insurgency. This was undoubtedly the case, but it fails to consider whether America even had such troops available in its volunteer force, and whether an all-hands-on-deck effort to pacify Iraq was the best strategic use of its limited military machine.

- The failure to deter Iran and Syria, which gave sanctuary and support to Shiite and Sunni militants, respectively. True enough, but how exactly—short of an expanded regional war—could the U.S. have hoped to stop this? Iraq is in Syria’s and Iran’s neighborhood, just as the Caribbean is in ours. How could Washington not expect Syria and Iran to meddle so close to home?

- Coalition warfare wasn’t successful: the deployment of allied troops had political value but was “largely unsuccessful” because the allies didn’t send enough troops. This ignores the reasons why so few countries sent substantial troops to our aid in Iraq. It was because they considered such an invasion ill-advised, illegal, and, in many cases, immoral. Perhaps the U.S. should have listened carefully to its long-standing friends.

- The failure to develop self-reliant Iraqi forces. Well, of course. But if eight years (2003 to 2011) of training and funding a new Iraqi army wasn’t enough to make them self-sufficient, and if 17 years hasn’t been enough to do the same in Afghanistan, might not the entire theory of America’s ongoing “advise & assist” missions need to be rethought?

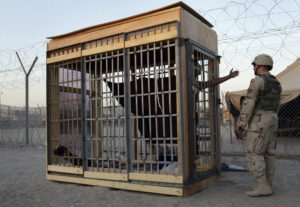

- An ineffective detainee policy: the U.S. decided at the outset not to treat captured insurgents and militia fighters as prisoners of war and many Sunni insurgents were returned to the battlefield. This ignores Guantanamo, and, most likely, the national-level global detainee policy of the U.S. Perhaps indefinite detention of suspected insurgents or “terrorists,” without any recourse to due-process, created more enemies than it imprisoned. Think Abu Ghraib.

- Democracy doesn’t necessarily bring stability: U.S. commanders believed the 2005 Iraqi elections would have a “calming effect,” but instead they exacerbated ethnic and sectarian tensions. A more holistic analysis would question the very capacity of a foreign military occupation force to impose democracy in an ancient locale at war with itself.

There’s also a personal connection here. The leader of the study team was Colonel Joel Rayburn. At first glance, no one is more qualified. Rayburn is brilliant and someone I hold in high esteem. He taught me British History at West Point, performed quite well on a popular TV trivia show, and wrote an interesting book on Iraq. Then again, Colonel Rayburn was deeply involved in the planning and execution of the famed “surge,” and is rather likely to glorify a military campaign (one this author fought in) that ultimately failed in its purpose—to stifle violence long enough to stabilize and form an inclusive Iraqi government.

Sure, violence drastically, if temporarily, decreased, but that was mainly due to a short-term alliance with former Sunni insurgents (many of whom had American blood on their hands). In the end, all that the roughly 1,300 U.S. troops killed during the surge achieved was the long-term entrenchment of a Shiite chauvinist prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki. His corrupt government in Baghdad alienated the very Sunnis once on America’s payroll and caused a new outbreak of sectarian violence. Many of those Sunnis later allied with or joined ISIS, seeing the group as their best protection. Looking back, that’s far from an encouraging outcome for a “surge” in which so many American servicemen were killed.

A truly expansive history (or study) of the Iraq war (perhaps best commissioned by a government agency besides the military) would admit to the much broader failures of the U.S. adventure in Iraq. It would certainly discuss the tactical and operational failures included in the current report, but it would also focus on the scarcity of American grand strategy. Such a study would question whether external military intervention is even capable of reordering and stabilizing ancient societies. It would include an honest cost-benefit analysis and ask whether the proverbial juice was worth the squeeze in Iraq. Did that war make America safer? Unlikely. Was it necessary? Undoubtedly not. These are the true takeaways from what will someday be remembered as one of America’s great foreign policy debacles.

The safe bet is that little to none of this will be in the report, when—or if—it ever sees the light of day. We shall see, of course, but this much is certain: an entire generation of American troops dedicated the greater part of the last 15 years of their lives to the war in Iraq. I left four soldiers and the remnants of my emotional health in Baghdad. Others suffered far worse—notably average Iraqis. We deserve a comprehensive, honest, and critical analysis of that debacle.

Whether we ever get one remains to be seen.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.