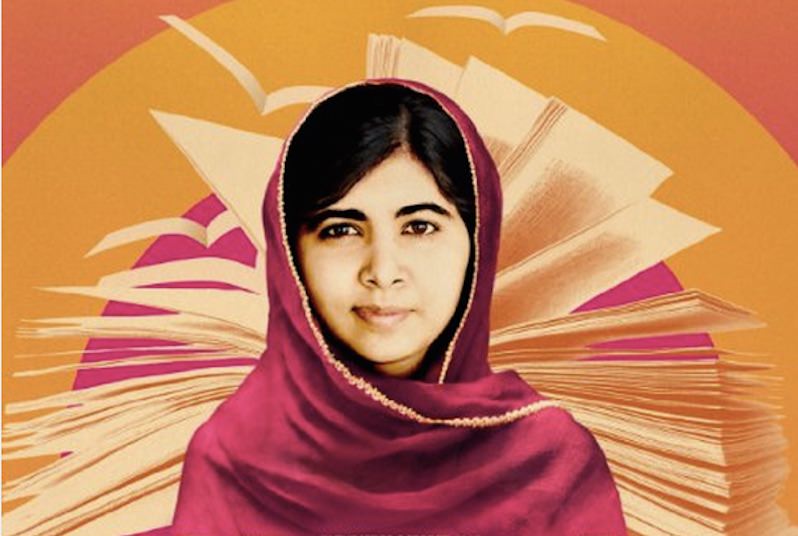

‘He Named Me Malala’ Film Review: Who’s Behind the Persona?

Filmmaker Davis Guggenheim documents the public side of the world-famous Pakistani education crusader but gives us only fleeting glimpses of the real girl. IMDb

IMDb

By now most everyone knows something about the remarkable Malala Yousafzai, the 18-year-old Pakistani youngster whose impassioned crusade for girls’ education nearly left her a martyr at 15, when a Taliban gunman shot her in the face in an assassination attempt.

“He Named Me Malala,” from filmmaker Davis Guggenheim (“An Inconvenient Truth”), announces itself as a profile of the world’s most famous teenager, treating her as a combination of Anne Frank and Joan of Arc. Despite the film’s honorable intentions, it is less a portrait than a beatification, compiling evidence for its subject’s eventual canonization.

From its early scenes, which include animated sequences rendered by artist Jason Carpenter in dreamy pastels, Guggenheim connects Malala with her legendary Afghan namesake, Malalai of Maiwand — the 19th-century freedom fighter was shot while rallying her people to resist invading British-Indian forces. Similarly, from the tender age of 11, Malala resisted Taliban occupation and its efforts to prevent girls and women from receiving an education.

The implication here is that nomenclature is destiny; that in naming her, Malala’s father, a charismatic educator like his daughter, prayed and hoped for a child of extraordinary convictions and bravery. The sense of prophecy fulfilled lends an aura of holiness to the film. This is at odds with other sequences showing Malala at home with her family and at school with her classmates in Birmingham, England, as an ordinary teenager with ordinary adolescent angst, afraid to confide in her schoolmates. Out of modesty, she wears a headscarf and longer skirts than the others, some of whom have boyfriends while she nurses Internet crushes on cricket stars and movie actors.

After the assassination attempt, a medically induced coma and many surgeries, Malala awoke to find the left side of her face paralyzed. It left her with a lopsided smile, but in no way did it impede her eloquence or fervor. On her 16th birthday, she delivered a rousing pro-education speech from the United Nations headquarters in New York City. At 17, she won the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the youngest person to do so. Oddly, Guggenheim does not tell her story chronologically, perhaps in adherence to the Jean-Luc Godard dictum that films have beginnings, middles and ends, but not necessarily in that order.

Thus viewers don’t know when the very engaging sequences of Malala, a natural-born educator, teaching female students in Kenya and Nigeria, take place. But it’s clear from the faces of her pupils how inspiring it is to see a girl with such passion and clarity up there at the whiteboard.

In such sequences of the public Malala, Guggenheim’s film is most powerful. Yet it’s a challenge for the documentarian to get her to show a private, human face.

In a rare moment, she does. “If I were from a conservative family,” Malala finally admits, “I would have two children by now.” Which is the closest she comes to criticizing the fundamentalists who tried to kill her.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.