‘Hostiles’ and the Politics of Modern Westerns

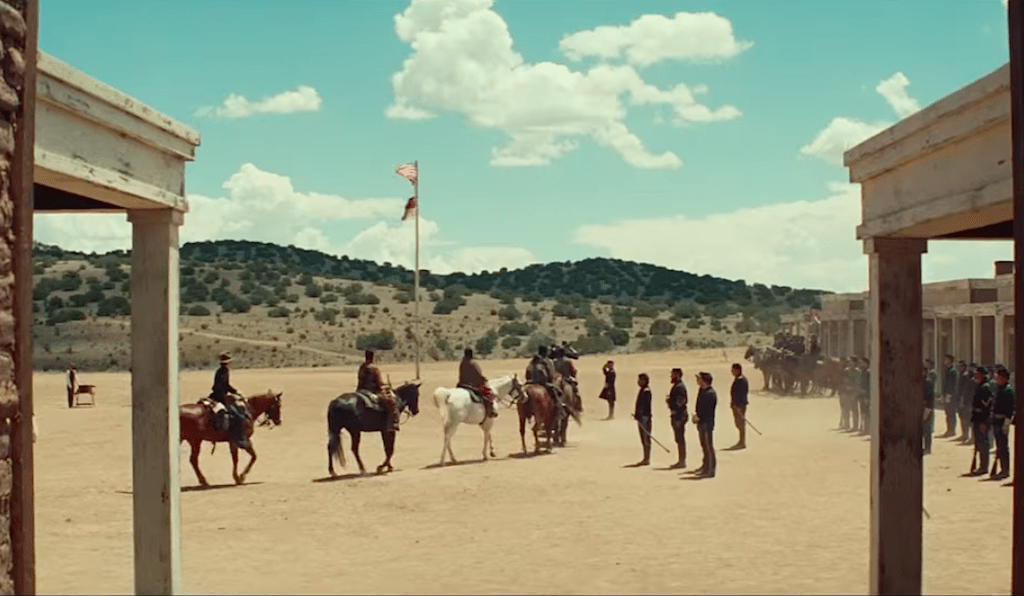

This seems to be the fate of the genre now: It must relate and appeal to 21st century notions of class, race and gender. A scene from Scott Cooper’s new film, "Hostiles." (Screen shot via YouTube)

A scene from Scott Cooper’s new film, "Hostiles." (Screen shot via YouTube)

The title of Scott Cooper’s new film, “Hostiles,” may be meant to be ironic.

In the 19th century, “hostiles” was the official designation for Indians at war with the United States Army, but “Hostiles” is not really a Western in the sense of those made by John Ford and Howard Hawks. The aim of the new Westerns like “Hostiles”—let’s call them post-Westerns rather than the popular term from the 1960s, anti-Westerns—is to go back and fill in the genre, offering points of view of characters other than white men, who dominated Westerns for more than half a century.

Cooper, who made the superb film about an aging country music singer, “Crazy Heart,” and an underrated film about Boston Irish gangsters, “Black Mass,” is aiming for nothing less than an epic. He’s got an outstanding cast with Christian Bale, Rosamund Pike, Jesse Plemons, Ben Foster, Stephen Lang, Adam Beach and Wes Studi. (After playing a Pawnee in “Dances With Wolves,” an Iroquois in “The Last of the Mohicans,” the Apache leader in “Geronimo,” and now a Cheyenne in “Hostiles,” Studi seems bent on representing every tribe in North America).

The cinematography by Masanobu Takayanagi is never less than spectacular, from the rock caverns and cliffs of the Southwest to the plains and forests of Montana. Cooper based the script on a manuscript by the late Donald F. Stewart (“Missing,” “The Hunt for Red October”) which took real incidents from numerous period journals and histories.

Like nearly all movies about the West since the 1960s, “Hostiles” tries to be reverential to the Western classic while correcting the limited or flawed narratives of the frontier. For instance, a black trooper, played by Jonathan Majors, is one of Capt. Joe Blocker’s men, but there wasn’t an integrated unit in the Army until 1944.)

So, I think, it’s fair to judge the film, at least in part, on its historical accuracy.

Two warnings about what follows. First, spoiler alert.

Second, I’m going to use the word “Indian” instead of Native American because Indian was what they were called back then. I resist the term Native Americans for the reason offered by Gen. Ulysses Grant’s aide, Eli Parker, a full-blooded Senecan, to Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox when the latter remarked, “Glad to see one real American here.” Parker replied, “We are all Americans, sir.”

Here’s a few of the historical distortions and outright absurdities:

● “Hostiles” takes place in 1892, two years after the massacre of Lakota Indians by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee in South Dakota and six years after Geronimo surrendered in Arizona. It also was just a year before Frederick Jackson Turner proclaimed the closing of the frontier in his famous thesis, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

The violence in “Hostiles” is so overwhelming that a significant portion of the film is spent with the participants burying the latest victims (cut out the burial scenes and you’d probably shave 30 minutes off the running time). But the frontier was pretty much settled by 1892. Surely the relentless bloodshed of “Hostiles” is suggestive of a much earlier era in American history by at least 20 years. Cormac McCarthy’s carnage-filled novel, “Blood Meridian,” which “Hostiles” owes more to than to any Hollywood Western, is set in 1849.

The only reason for placing “Hostiles” so close to the end of the 19th century would be to close out the various themes inspired by the old West in one neat package—too neat, finally, and overstuffed with modern relevance. This seems to be the fate of Westerns from now on: They must relate and appeal to 21st century notions of class, race and sexual politics.

● The film opens with a massacre of a white family by renegade Comanche. The father (Scott Shepherd) runs into the cabin to warn his family and grab his rifle, then, like an idiot, rushes out to fight off the attackers—armed Indians on horseback—and is, of course, killed instantly. He had a repeating rifle and could have easily stayed inside and fired from the shelter of his cabin. He also tells his family to try to escape through the back door and into the woods, an obvious homage to a scene near the beginning of Ford’s “The Searchers,” and things end just as badly for them with only the mother, Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike), surviving.

● Wes Studi’s Yellow Hawk is northern Cheyenne, but he’s been held prisoner in New Mexico for several years. He is dying of cancer, and public pressure fueled by the Eastern press has resulted in President Benjamin Harrison issuing an order to free Yellow Hawk and his family and escort them back to his homelands in Montana. The Army is responsible for returning him safely, and Blocker (Christian Bale) is ordered to take him there. This is nonsense: The Army would have no jurisdiction in this case, nor would it be responsible for escorting an Indian back to his home. That would be a job for U.S. marshals. But using a lawman would deprive “Hostiles” of the iconic blue uniform of the U.S. Cavalry of films such as “Fort Apache,” “Rio Grande” and “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon.”

And if there was an explanation for why a Cheyenne from Montana was being held more than 800 miles south of his homeland, I missed it.

● After finding Rosalie Quaid in the burned-out cabin with the remains of her murdered family and taking her to the nearest outpost, the widow decides not to wait in safety and relative luxury for a train back east, which will take months. Instead, she decides to accompany Blocker and his men on the trek to take Yellow Hawk home, and they saddle up a horse for her. Are all the characters who agree on this decision nuts? The soldiers are riding through hundreds of miles of territory inhabited by wild beasts and murderous men of various races, to say nothing of the threat from weather.

Just in case matters weren’t desperate enough, the commanding officer asks Blocker if he would mind taking a soldier-turned-ax-murderer with them and veer off only a couple of hundred miles to drop him at another post to be tried and probably hanged. Then, the commander somehow neglects to send along a squad of his men to guard the prisoner. Oh, I forgot to mention that the prisoner is Ben Foster, so you know he’s going to need some guarding.

● Just as the party finally reaches Montana, Yellow Hawk passes on. As the Cheyenne burial ceremony is completed and you think Studi’s spirit is finally at peace, the group is accosted by four angry white men on horses, a rancher (Scott Wilson) and his three sons, who demand they dig up the Indian and leave their land.

Bale refuses and produces the warrant from President Harrison authorizing the Yellow Hawk’s burial at that spot. The rancher and his sons spew venom and hatred, and a fight ensues in which the Widow Quaid fires the first shot. Everyone dies except the captain, the widow and an Indian boy. (Thank the Great Spirit that the movie didn’t stop to show us yet another burial service.)

There are so many things wrong with this scene that it’s hard to know where to begin. Let’s start here: If Wilson’s rancher owns the land, he is fully within his rights to dictate that no Indian or anyone else be buried there, warrant or no warrant from the president. And if it’s government land, the rancher shouldn’t be on it in the first place (unless he’s an ancestor of Cliven Bundy). When the rancher questions—with a smirk—whether the widow will fire her rifle, she proceeds to kill him. For some unexplained reason, the movie doesn’t regard this as murder, presumably because the rancher is so sexist and racist that he deserves to die. In fact, the killings of the rancher’s sons also count as murder.

Which leads to another point: Why, in a movie where everyone’s backstory is given, isn’t the rancher allowed his grievances? Presumably, his hatred is based on a decades-long blood feud with the Cheyenne, but we don’t get a chance to hear their story. For that matter, neither do we learn anything about the Comanche who slaughter the Quaid family at the beginning of the movie.

One characteristic of Westerns over the last 30 or so years is an odd dichotomy where good Indians must be balanced by bad Indians. In “Dances With Wolves,” for instance, Kevin Costner’s cavalry officer comes to bond with his Lakota neighbors and even helps them in their war against the murderous Pawnee, who are seen as the aggressors (even though the Lakota were far more numerous) and made up to look like the biker gang in “The Road Warrior.” The Comanche were long subdued by 1892, but “Hostiles” uses them pretty much the way John Ford used them in “The Searchers”—as terrorists.

“Hostiles” is wonderfully acted and beautifully photographed and has been rightfully praised by many critics. But as the credits rolled, the audience didn’t know how to react. At the heart of “Hostiles” is a conflicted sense of our country’s bloody history, one that can’t be reconciled by the purchase of a movie ticket.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.