How Can a Scientist Make Sense of the Religious Impulse?

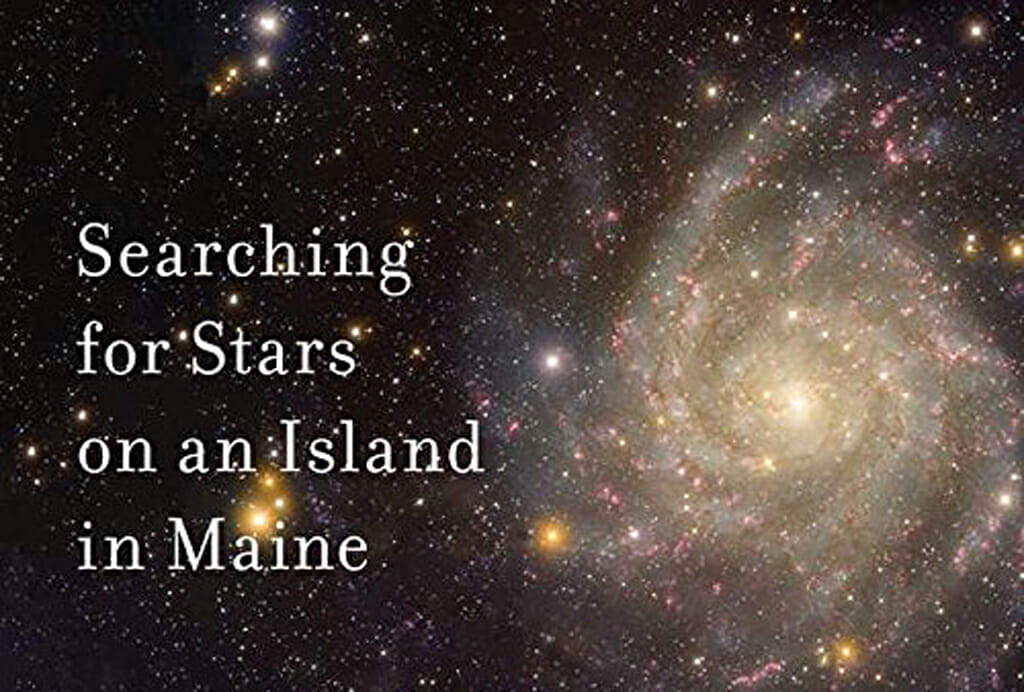

Physicist Alan Lightman ponders this and other questions in his new book, "Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine." Pantheon

Pantheon

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

“Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine”

A book by Alan Lightman

Science writers generally fall into one of two categories: Some of us are textbook authors trying to convince ourselves that we are storytellers, while others are journalists who aren’t real scientists but like to play them on TV. Alan Lightman, however, is different. He is the poet laureate of science writers. His best-known book, “Einstein’s Dreams,” a lyrical novel putting us inside Albert Einstein’s mind as he makes his great discovery, established him as the Picasso, the Schoenberg, the Gehry of science writing. He didn’t just do it better—which he did; as a wordsmith Lightman stands alone among science writers—he did something with the genre no one imagined could be done. He created narrative poetry from relativity theory that was nothing short of magical. So, when a new work by Lightman emerges, the excitement is legitimate.

“Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine” is what we can call a grand unified intellectual narrative. Lightman points out that most physicists have a motivating belief in a final theory, a grand unified theory, a theory of everything. There must be, they hold, a single, elegant, ultimate law of nature from which the rules that govern all observable phenomena can be derived. Similarly, science writers long for a grand unified intellectual narrative, a discussion of everything, a single coherent conversation that will unite the great insights of physics, philosophy, religion, biology, art, neurology and sociology. This is Lightman’s.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine” at Google Books.

But to give an account of everything, you have to know what constitutes everything. As a physicist, Lightman felt secure that our best current theories tell us. Sure, there are the worries about dark matter and dark energy, but scientific methodology, which exposed these problems in the first place, will ultimately supply us with the answers.

Then he took his boat out to his summer home on Pole Island, Maine. It was a beautiful night, and Lightman cut the engine and lay down on the deck. Floating silently in the night, looking up at the stars, he felt himself transported out of his body, floating up among the heavenly lights, feeling a deep sensation of connectedness—not only Lightman with the stars, but of all things. It was a spiritual experience.

This epiphany was real. It was undeniable. But Lightman is a materialist. He does not believe in a nonmaterial soul, much less a supernatural God. How can one square the reality of the spiritual experience with the belief that the material world is all there is to reality? Can one have transcendence in a universe that cannot be transcended? How can a scientist, who buys the assumptions on which the scientific worldview is based, make sense of the religious impulse?

This is the question of the book. There are three different approaches to the spiritual. Philosophers label them religious rationalism, fideism and phenomenology. Rationalism is the view that we can demonstrate the likely or certain existence of God. Fideism holds that proof of God’s existence is irrelevant as religion requires faith, not reason. Phenomenology contends that religion is not a matter of believing at all but of feeling. Spirituality is a result of lived experience, not abstract propositions.

Lightman tries all of these on in turn, reaching for the writings of great minds from a wide range of times, places and traditions. We are treated to discussions of Aristotle, Einstein, Tagore, Shakespeare, Augustine and Galileo. From Buddhist monks to Lightman’s rabbi to physicist and atheist Steven Weinberg, no perspective is eliminated from being a possible source of insight and wisdom. Each is examined to see if it is possible to believe in both our best scientific theories and some sense of the spiritual.

The book comprises 20 short vignettes, each dedicated to a big idea—stars, truth, centeredness, death—weaving together expected and unexpected sources. The sections are short but thoughtful, allowing the reader to savor a piece at a time or to make a meal of the whole.

The approach is synthetic, not analytic. Distinctions and incompatibilities between perspectives are shown, but judgments are never rendered. In treating all viewpoints with the utmost respect, the book does, at points, feel like “Chicken Soup for the Materialist’s Non-Existent Soul,” but those moments are few, in a work of great range, sensitivity and thoughtfulness.

Lightman’s preference emerges for the phenomenological. “For me, as both a scientist and a humanist, the transcendent experience is the most powerful evidence we have for a spiritual world. By this I mean the immediate and vital personal experience of being connected to something larger than ourselves, to feeling some unseen order or truth in the world.” Even this, he worries, may be a step too far as it requires that consciousness be considered itself a real thing in the world. Would that mean “I” would have to be more than the neurochemical interactions occurring in my brain? Can a materialist take that step?

“Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine” demonstrates Lightman’s ability to make the most abstract notions accessible to all. No background is needed in physics, philosophy, religion or any other field to fully understand every step of the wide-ranging intellectual trek. No matter who you are, you will emerge ready to be more impressive at your next dinner party.

Of course, a path that overlooks so many vistas will sacrifice depth for the sake of breadth. If you have a significant background in any of the areas discussed, you will recognize the complexity that could come from a narrower but deeper exploration of the topic. But if you want a book about black holes, Buddhism or the brain, there are plenty of those out there. This is a grand unified intellectual narrative.

“Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine” reads like you are sitting on a lichen-covered bench on Pole Island alongside one of our best minds, exploring the geographic features of the entire intellectual landscape. No matter your views on science and the transcendent, this engaging read will be as pleasant as a summer afternoon spent on an island in Maine with good company.

Steven Gimbel is a professor of philosophy at Gettysburg College and the author of “Einstein: His Space and Times” and “Einstein’s Jewish Science: Physics at the Intersection of Politics and Religion.”

©2018 Washington Post Book World

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.