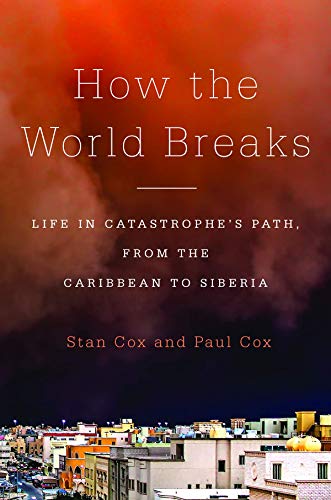

How the World Breaks

Welcome to the new frontier -- a place where intensifying catastrophes driven by climate change have already forced people around the world to make life-altering decisions.Welcome to the new frontier—a place where intensifying catastrophes driven by climate change have already forced people around the world to make life-altering decisions.

New Press

| To see long excerpts from “How the World Breaks” at Google Books, click here. |

“How the World Breaks: Life in Catastrophe’s Path From the Caribbean to Siberia”

A book by Stan Cox and Paul Cox

In “How the World Breaks,” a father-and-son-team, Stan Cox and Paul Cox, show us a world where the catastrophes caused by a changing climate are becoming more powerful and occurring with increasing frequency. The men, women and children who live in the cities, villages and slums affected by these disasters display admirable resilience, braving harsh conditions to save their homes and families. Every natural disaster presents those directly affected with a choice. Those threatened by the planet’s changing climate, especially in vulnerable areas, can dig in their heels to defend against future disasters. If resources are available, they can rebuild their homes after the storms come through. Alternatively, before an imminent disaster or in the aftermath of one, these people — again, if the resources are available — can leave. These towns can be written off, their wreckage transformed into buffer zones against future catastrophes. This is the world the Coxes foresee, one in which catastrophes become so destructive and so frequent as to make it all but impossible to stay in certain areas of the globe. There will be a general retreat of those who once lived in these violent, chaotic lands to safer areas.

The Coxes’ portrayal of life on this new frontier — where intensifying disasters have become a reality — is stark but not alarmist, which makes their book highly readable. They take us around the world to societies where governments and citizens have already been forced to make decisions in the face of disasters caused by corrupt and reckless industrial practices and a changing climate. Their citizens can stay and fight against these natural and man-made catastrophes, rebuild, or abandon their homes and livelihoods. They also show us coastal cities, such as Miami, where residents have not yet had to make that choice. In other parts of the world, from Indonesia to the East Coast of the United States, people are only just beginning to realize how limited their options really are.

In rural regions of Victoria, Australia — the parts Australians call “the bush” — locals are just starting to see how devastating climate change is. Fires have become more intense, hotter and larger. They burn longer, too, often by a couple of weeks. The largest fires used to come every six or seven years. Now, such fires are an annual event. Those who grew up in the bush speak of fathers and grandfathers who embodied a hyper-masculine ideal by staying and fighting fires. Faced with rising death tolls, due in large part to increasing numbers of former urbanites moving to the bush, attitudes are changing. There are those who continue to fight. Women too have joined the ranks of firefighters and commanders in recent decades. Despite this, Victoria’s fire slogan was recently revised to a simple plea: “Leave and Live.”

For an example of a society that has been utterly destroyed, and whose lands have been left as a kind of buffer zone against future disasters, our authors travel to the island of Java, Indonesia, where a volcano erupted in 2006, slowly burying a nearby village in a foul-smelling gray sludge. A decade later, this goo continues to pour from the volcano. There is some evidence to suggest that industrial drilling in the area was responsible for the eruption. What is certain is that life for the surviving villagers was forever altered. Many are still living in refugee camps, undecided over a convoluted compensation scheme offered by the government and the drilling company. Levees now surround the volcano, along with frequent pumping operations, to prevent mud from spilling farther out on the island. That this sludge is pumped into a nearby river seems to worry only those scientists who have found elevated mercury levels in the water and its fish. Meanwhile, optimistic former residents hope to turn the mud flat into a destination resort and spa. Today, they charge travelers a fee to climb a set of bamboo and wooden steps to the top of the levee, where they can look out on the pool of gray sludge. A small consolation prize for men, women and children who once called the land home.

The book at its strongest details the human cost of the world’s changing climate. The picture it paints is a scary one, where eventually societies around the globe will simply fail to withstand the successive catastrophes. While the authors suggest that profound transformations at the level of governments and society would be necessary to address the roots of these catastrophes — climate change driven by human activity — they also foresee a “managed retreat” in “a dizzying world of unmanageable hazards.” The Coxes offer some interesting policy proposals, such as the creation of universal, single-payer disaster insurance programs in the United States. The authors do concede that many of their proposals would be, in today’s political climate, dead on arrival. They’re also persuasive in addressing the notion that continued economic growth or various plausible ecological developments, like the growth of new forests in the warming northern latitudes for instance, might stem the immense difficulties a changing climate will bring.

Meanwhile, the Coxes seem to suggest that resilient societies, bouncing back from disasters, actually allow governments to continue to avoid enacting policies addressing the anthropogenic factors driving climate change. The authors write, “So if we’re asking vulnerable communities to be the source of resilience, this is what we’re asking of them: to work constantly toward the capacity to absorb shocks and changes so that the rest of us don’t have to worry about those shocks and changes, and we can keep generating more of them. It’s the expendability of their time and enjoyment of life that makes all of global capitalism resilient.”

The Coxes ask a simple question: How long can these new frontiers hold, before we are all vulnerable? In doing so, they have done a remarkable job of putting a human face on a series of disasters normally overlooked or quickly forgotten. Whatever one thinks of the Coxes’ economic or social analysis, one thing is clear: If natural disasters continue to increase both in terms of sheer destructive force and frequency, then the questions compelled by these disasters will not just apply to those in faraway lands, but to our friends, family members and ourselves. It is perhaps appropriate that I am writing this in a house that is covered by federally subsidized flood insurance in Long Beach, New York. This happens to be the same city where, in March of this year, a $37 million contract was awarded to finance the construction of a dune barrier 7 miles long. The project will create “a more resilient waterfront,” in the words of Sen. Chuck Schumer. The tide is rising and the hurricanes will come but the government is doing what it can to fortify this small stretch of coastline. This little patch of sand will be less vulnerable than it was, once the dune is constructed, at least until rising tides and violent storms tear it apart. But what about the rest of Long Island, to say nothing of the rest of the East Coast? For our authors, this dune project is exactly the kind of uncoordinated, piecemeal resilience that allows the world to break, one small village, township or city at a time. How we might reach a more coordinated approach to preventing and reacting to natural disasters driven by climate change remains an open question, and an urgent one.

James Mumford is a writer living and working in New York City.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.