Intrepid Exile Mohammad Rasoulof Thwarts the Theocracy

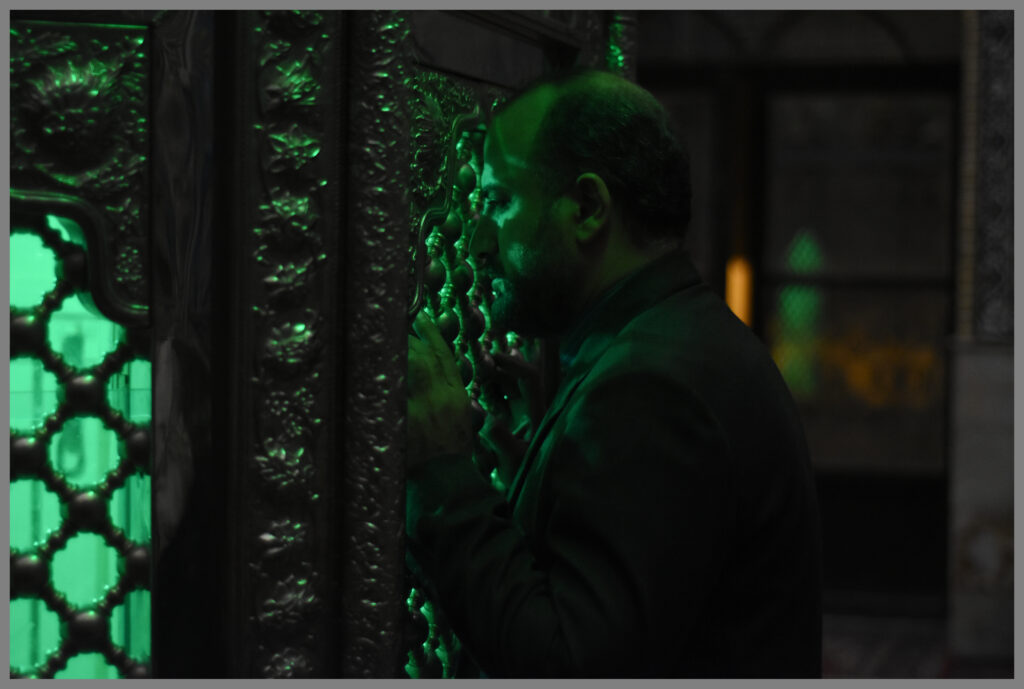

Iran’s outcast artist on the “gangsters of culture” and making movies under the mullahs’ noses. Image courtesy of NEON

Image courtesy of NEON

In September of 2022, a 22-year-old Iranian woman named Mahsa Jina Amini died after being detained for purportedly improperly wearing her hijab. The tragedy ignited mass protests aimed at Iran’s draconian “morality police,” who, in turn, commenced a brutal crackdown targeting women and girls. In a new film, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” Iranian writer and director Mohammad Rasoulof risked his freedom to dramatize and encapsulate the recent uprising — all while evading Iran’s security forces.

In “Sacred Fig,” Iman (Misagh Zare) is an apparatchik promoted to become an inspector for the Revolutionary Courts and fast tracked to become a judge, a coveted position in the Islamic Republic’s security apparatus. His promotion promises prosperity for his wife, Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) and their teenage daughters, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki). Najmeh zealously protects Iman’s career trajectory, but this Faustian bargain threatens to tear the family apart, even as the “Woman Life Freedom” protests explode across Iran. Like Bernardo Bertolucci in 1970’s “The Conformist,” Rasoulof probes the complicity of collaborators with totalitarianism.

Remarkably, Rasoulof and his cast and crew secretly shot “Sacred Fig” underground, largely in Tehran, right under the nose of the Headquarters for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. In May, facing an eight-year prison sentence and believing his re-arrest to be imminent, Rasoulof fled on foot over Iran’s mountains. On May 24, the dissident director presented “Sacred Fig” in person at the Cannes Film Festival to a 12-minute standing ovation. The film won four awards and a Palme d’Or nomination, and was selected as Germany’s submission for the Best International Feature Oscar.

“Sacred Fig” is reminiscent of the 1969 Palme d’Or winner, Lindsay Anderson’s “If….” which set the campus revolts then-sweeping the world at a British boarding school, just as Iman’s family, with its gender and generation gaps, symbolically serves as a microcosm of Iran. And Rasoulof’s combination of professional actors playing roles intercut with actual footage documenting the demonstrations and police brutality following Amini’s death, also calls to mind Haskell Wexler’s “Medium Cool” from 1969, which shot the actors Robert Forster and Verna Bloom amidst the Democratic National Convention riots in Chicago 1968.

Now living in exile in Germany, Rasoulof was born in 1972 in Shiraz, Iran, and has been making movies for about 20 years. His many accolades include the Berlin International Film Festival’s Golden Berlin Bear for 2020’s “There is No Evil.” With his new scathing epic about crime and punishment in Iran, Rasoulof is arguably to the Islamic Republic what Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov was to czarist Russia. He was interviewed with the assistance of an interpreter (whose face was blurred) via Zoom in New York.

TRUTHDIG: Can you say where you currently are or are you at an undisclosed location?

MOHAMMAD RASOULOF: No, I’m in New York, because we’ve had screenings here.

TD: Your films have never been publicly screened in Iran, despite winning awards overseas. Is this how the Islamic Republic’s regime punishes you for your work?

MR: Yes, I’ve made eight features so far, not one of which has ever been screened inside of an Iranian cinema or any official screening. Until this day, I have yet to see some of my own films inside of a cinema, because I was banned from leaving the country for many years, and this possibility did not exist. So, the first thing the Islamic Republic does is try to interrupt my relationship with my primary Iranian audience.

Then, of course, there’s been imprisonment, interrogations, court cases and, in fact, as I talk to you today, there’s an eight-year prison sentence awaiting me in Iran, which pertains to previous films. Not even to “Sacred Fig” — that would be a whole lot [more prison time] in its own right. If I were to go back to Iran one day, I’d probably have to go to prison straight away.

TD: The death of Mahsa Jina Amini and ordering of the death sentence for rapper Toomaj Salehi are just some examples of state violence, how have artists and protestors weathered theocratic repression in Iran

MR: The repression of artists began a long time ago. Perhaps with the beginning of the Islamic Republic, with many artists being forced into exile, and many of them never being unable to continue, many artists being killed. You can say a theocracy has a religious problem when it comes to art. Artists have been trying to keep working for decades and navigate a way in this new world, but not everyone manages to comply with censorship or not resist openly to censorship. Those who do face a quite harsh reality.

“Theocracy has a religious problem when it comes to art.”

Of course, today we live in a very different world compared to 40 years ago or more. The world is highly interconnected. For instance, at the beginning of the revolution, the Islamic Republic could get away with quite a lot of killing without attracting much attention. It cannot do the same today, because the news circulates through all these channels, and it does so at a great speed. So, exerting violence the same way is not as easy for them as it once was.

At the same time, whenever a significant protest movement takes off, the state immediately reveals its violent face; and we’ve seen this clearly since 2022 with this last [link] in the chain of the struggle for women’s rights in Iran, the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, where the state, with no qualms, showed itself as it is, killed many protesters, blinded many others and sent huge numbers of people to jail. It revealed itself as a totally inhumane entity.

TD: In “Sacred Fig,” you dramatize the harsh crackdown on what some have called the Jina revolution, including its hardline measures. After Iman is promoted to inspector, his co-worker, Ghaderi, urges him to agree to a captive’s death sentence — even though Iman hasn’t even read the case files.

MR: Today, as we speak, the same reality is unfolding in front of our eyes. In Tehran, six young men have been sentenced to death and the judge is refusing to sign their execution order. It’s very unfortunate that my inspiration should be based on real stories from my society.

The question of the film is: What characteristics do these people who collaborate with the system have? What enables them to do so?

TD: The film is more than a portrait of a single family.

MR: A family, as the most specific, small unit of a society, can represent at times society on a wider scale. I was very keen for the film to start out as a family drama, then expand and change gears and then become a film where this family drama is projected against a background of the history of Iran.

TD: You worked right under the noses of the mullahs. How did you manage to make the film in such a rigidly controlled and surveilled police state?

MR: [Smiles.] Every time they sent me to prison, I learned new tricks, how to better circumvent them. To such an extent that perhaps our job as filmmakers, as a cast and crew, is very similar to that of gangsters. Albeit we are the “gangsters of culture.”

To make underground films you always have to follow quite strict protocol. You have to change and devise every time you want to make a new film. Because it really depends on what you want to make and what the circumstances are. In this film, we decided to stick to three main principles: to have a very small cast and crew, use very limited and light equipment, and direct remotely at a distance from the set.

TD: What led you to flee the Islamic Republic?

MR: The last time I was in prison, I knew that I probably was going to be sentenced to a long prison sentence. I reflected a lot upon what it meant to be a filmmaker in prison. I thought yes, you might still be a filmmaker, but you’ve really turned into a victim of censorship and the fact is you really can’t get anything done in prison.

“Every time they sent me to prison, I learned new tricks.”

I realized, actually — I had so many ideas and plans I wanted to get done, other films —that were I to receive an eight-year prison sentence, I should leave the country. You always think of the negative aspects of prison, but this last time I was in prison it had some positive aspects. I got to know people who told me: Were you ever to decide to leave Iran illegally, let us know, we can help you. That’s what I did, and they enabled me to leave Iran and reach safety.

I left Iran on foot through the mountains. I can not tell you which neighboring country I crossed into, but I can tell you that once there, I contacted the German consul, since my family had been based in Germany for a long time. Once they ascertained my identity, they helped me get to Germany.

TD: What about your cast and crew?

MR: A few days before news of the film got out the young actresses were able to leave the country. Then, once they knew about the film, [the authorities] exerted a huge amount of pressure on the cast and crew inside the country, which means they interrogated everyone multiple times, prevented everyone from leaving the country, and banned people from working. They increased the pressure more and more, in order that my main collaborators would request me to withdraw the film from the main competition at Cannes.

Then, the pressure decreased a little bit. However, we are currently being investigated, and some of us will be judged in absentia inside the country on three charges: act against national security; propaganda against the regime; and spreading corruption and prostitution on Earth.

TD: The film includes footage of demonstrations and police brutality, intercut with dramatic scenes. Where did these real-life sequences come from?

MR: The footage is taken from protesters themselves, because in Iran, due to censorship and repression, journalists are not allowed to document protests. So, it falls upon protesters themselves, who have been documenting protests for a long time. At this time in history, they use mobile phones to capture footage, which they then circulate online.

I was making a film about a family that had become trapped within an apartment so it became very important to show what was happening outside on the streets. And here I was making an underground film, it was impossible to even think of potentially reconstructing such scenes on location.

TD: At the film’s end, Iman drives the family to his childhood home near ruins in the remote countryside. Does this symbolize that regime apparatchiks like Iman are out of touch and stuck in the past?

MR: It certainly shows there is this ongoing battle between the young generation and older generation that relates to tradition and modernity.

TD: What’s next for Mohammad Rasoulof?

MR: Well, you know I’m a filmmaker, so naturally I think about making films [laughs]. I’m currently very busy with all the travel, accompanying the film around the world. I can not wait to sit down at my table and decide which film to get started on.

“The Seed of the Sacred Fig” is 168 minutes long, in Farsi with English subtitles and theatrically opens Nov. 27.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.