Jane Ciabattari on Emily Dickinson’s Friendship With Abolitionist

A new book by Brenda Wineapple sheds light on the little-known relationship of the reclusive genius poet with one of America's most fervent radicals.

How many know that Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the radical abolitionist who was one of the “Secret Six” who supported John Brown’s bold raid on Harpers Ferry, later became the literary confidant of the reclusive apolitical poet Emily Dickinson?

Higginson is the question mark in this equation. Dickinson has been the target of more than a century of obsessive scholarly excavation.

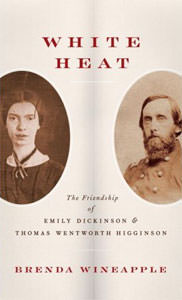

In “White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson & Thomas Wentworth Higginson,” Brenda Wineapple, biographer of Hawthorne, Janet Flanner, and Gertrude and Leo Stein, explores the curious 24-year relationship between the Amherst, Mass., poet and Higginson, her designated tutor and critic. Wineapple makes a case for a parallel sensibility, iconoclasm, fanaticism and courage. She captures the intellectual and political climate of New England in the last half of the 19th century and sheds light on Higginson’s radicalism. “Braced by the righteousness of his cause — the unequivocal emancipation of slaves — this Massachusetts gentleman of the white and learned class had earned a reputation among his own as a lunatic,” she notes.

Wineapple begins her narrative with the first letter the poet, then 30, wrote to Higginson, in April 1862 at the raw front edge of the Civil War. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” Dickinson wrote.

Why Higginson? Dickinson had read his work in The Atlantic, where he wrote about slavery, women’s rights, gymnastics, flowers, birds and the changing seasons. He had shown himself to be a man “willing to risk everything for what he believed,” Wineapple notes. He was forced to resign as minister of a Newburyport, Mass., congregation in 1849 because of his abolitionist fervor (he had railed against the slave-owning presidential candidate Zachary Taylor from the pulpit). He wielded a battering ram at the Boston Courthouse door in 1854 in a failed effort to free the fugitive slave Anthony Burns. In 1856, with “a loaded pistol in his belt,” he helped arm antislavery settlers in Kansas. (Upon his return, he predicted the coming conflict: “Kanzas [sic] may be crushed, but not without a final struggle …which will convulse a continent before it is ended, and separate those two nations of North and South, which neither Union nor Constitution has yet welded into one.” He helped buy the rifles John Brown and his followers toted into Kansas, and after the raid at Harpers Ferry, Va., contributed to his defense. (Brown was hanged in December 1859.)

When Higginson received the unsigned letter from Dickinson, he had just published “Letter to a Young Contributor” in The Atlantic, exposing himself to a flood of pleas for literary guidance. The four poems she enclosed, he wrote later, gave him “the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius.” Among them was “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers — .” (Dickinson coyly neglected to mention it already had been published in the Springfield Republican, which was owned by her friend Samuel Bowles).

Imagine. These poems, with their “metrical forms jagged, their punctuation unpredictable, their images honed to a fine point, their meaning oblique, elliptical, heart-gripping, electric,” as Wineapple puts it, may as well have been dropped into his Worcester mailbox from a future century. Higginson later called it “poetry torn up by the roots that took his breath away.”

Born into the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, Dickinson had resisted it wholeheartedly, ending her school career at Mount Holyoke Seminary at age 17 as a “no-hoper,” resistant to religious conversion. Thereafter, she wrote, “Home is the definition of God.” When she initiated her correspondence with Higginson, Dickinson was living in her family Homestead with her parents and her sister Lavinia; her brother Austin and his wife, Susan, to whom she was deeply attached, were next door.

He responded at once, asking whether she published, and would she, and making a few editorial suggestions. She termed this “surgery” in her immediate second letter, but added, “It was not so painful as I supposed.” She asked him to be her teacher, and he agreed. That summer she sent him “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’ ” and three others. “Dickinson had thrown down the glove, daring him to watch her perform,” Wineapple writes. Over a near quarter-century, Dickinson’s most productive years, she sent him drafts of nearly 100 poems. “You were not aware that you saved my Life,” she wrote several times, referring to a mysterious grievous loss.

In November 1862, at age 38, Higginson became head of the first federally authorized regiment of former slaves in American history. His First South Carolina Volunteers predated by five months the celebrated 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a Union regiment of free African-American men led by Robert Gould Shaw.

In her chapters on Higginson’s war years, Wineapple gives a glimpse into the rarely ballyhooed history of the Union Army’s black soldiers and seamen and the white officers who led them. (Some 200,000 of them are commemorated in the 10-year-old African-American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C.) She draws upon Higginson’s Civil War journal and letters, his official reports, his essays. She also reminds us of his minor masterpiece, “Army Life in a Black Regiment, ” a collection of Atlantic essays based upon his war journals and the story of his three military expeditions, infused with his sense of the “valor of the black soldier — and his outrage that black soldiers had been underpaid when paid at all.”

Back in Amherst, Dickinson published a handful of poems anonymously in various newspapers, in part for the war effort. These were among the few to appear in print in her lifetime.

After the war, while The Atlantic’s new editor, William Dean Howells, noted the nation had “grown tired of racial issues,” Higginson stayed the course for many years. His postwar writings rail against the betrayal of the fighting men he saw in action. He denounced Northern “colorphobia” and President Andrew Johnson’s reconstruction plan, which restored confiscated land and congressional seats to the Southern rebels. A stalwart in the women’s suffrage movement, Higginson also launched the careers of dozens of literary women, including Charlotte Hawes, Harriet Prescott Spofford, Emma Lazarus and the poet and novelist Helen Hunt Jackson. Yet still he discouraged Dickinson from publishing. “Nudging open literary doors for Helen Hunt, he could have done the same for Emily Dickinson,” Wineapple writes. “One suspects he would have, were she tractable, which she was not. Her own ambivalence about publishing her work, her own tensile strength, and her choice of an alternative route of publication — circulating her poems among friends, nurturing her reputation by piquing curiosity — rendered moot what Higginson could offer. …”

The two correspondents met for the first time in the summer of 1870, eight years after that first letter. Higginson went to the Homestead, where Dickinson greeted him clad in white, offered him two daylilies, and talked nervously for hours. Afterward he told his wife, who considered Dickinson crazy, “I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me.” He visited her only once after that, despite her many imploring letters.

Dickinson wrote at once when Higginson’s wife, Mary, long an invalid, died in 1877. “The Wilderness is new — to you,” she wrote. “Master, let me lead you.” There is a sense of possibility in her tone, and she urged him once again to see her. But rather than another trip to Amherst, Higginson went south, revisiting scenes of his military life, and spent some time in Europe. Upon his return, he married Minnie Thacher, who was 22 years younger. They had two daughters, the first of whom died in infancy (alert to loss, Dickinson sent him a touching condolence letter). The correspondence dwindled, as did the output of poems. Dickinson’s father died, then her beloved nephew, her mother, her friend Samuel Bowles. The string of losses mounted. Her health declined.

Wineapple notes that “White Heat” is not conventional literary criticism or biography (she tips her hat to Richard B. Sewall’s “The Life of Emily Dickinson” and others). Her focus is on the letters, the poems, the parallel lives. “White Heat” certainly brings to the fore the lifework of these “two unusual seemingly incompatible friends” and draws a plumb line from their time, with its tension between solitude (whether at Walden Pond or in Amherst) and activism, and ours. “The fantasy of isolation, the fantasy of intervention: they create recluses and activists, sometimes both, in us all,” she writes.

The two met only twice, and most of Higginson’s letters to Dickinson were lost or destroyed, although their context lingers suggestively in many of Dickinson’s responses. The drama in “White Heat” comes from Wineapple’s exquisite setting of scenes, her incisive explication of the work, and her portrayal of the intellectual and political ferment within which the two maintained their commitment to Dickinson’s artistic “offspring.”

Wineapple also makes a case for Higginson as Dickinson’s sometime muse. Her “As imperceptibly as Grief,” with its description of summer departing, Wineapple notes, “may be her description of him; the guest that would disappear, if he ever came, and her idea of him never quite fulfilled by his presence.” They were able to “invent each other,” to “speak to each other without bounds,” Wineapple notes. “For their link was words — their letters, her poetry, his essays. Words meant everything to her and a great deal to him.”

After Dickinson’s death in May 1886, her sister Lavinia discovered the hundreds of poems and letters in her room and was determined to have the work published. Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd (the interloper whose affair with Emily’s married brother Austin caused much consternation) co-edited the first posthumous Dickinson volume. Simply titled “Poems,” it was a slim volume, bound in white, with gold trim and silver Indian pipes on the cover. The two of them flattened out Dickinson’s idiosyncratic diction, punctuation and capitalization to match the conventions of the day. Higginson may have “saved her life,” nurtured her genius and helped midwife her work into print, but future literary critics and scholars condemned him for bowdlerizing her work. Wineapple shows how lifeless the edited versions were in comparison to the preternaturally Modernist originals (these were not restored until 1955, when “Poems of Emily Dickinson” was published by scholar Thomas H. Johnson).

“I feel as if we had climbed to a cloud, pulled it away, and revealed a new star behind it,” Higginson noted when that first volume appeared. The book went back to press 11 times, and the eminent William Dean Howells wrote, “… if nothing else had come out of our life but this strange poetry we would feel that in the world of Emily Dickinson, America, or New England rather, had made a distinctive addition to the literature of the world. …”

Having urged her to delay publication in her lifetime, Higginson witnessed the overwhelming response to her work: “Few events in American literary history have been more curious than the sudden rise of Emily Dickinson into a posthumous fame only more accentuated by the utterly recluse character of her life and by her aversion to even a literary publicity,” he wrote in the October 1891 Atlantic.

Higginson died in 1911, at 87. He was remembered mostly as a “bungler,” (Amy Lowell’s term) for his role in altering Dickinson’s work. He was dismissed within months of his death by Harvard scholar George Santayana as one of a faded genteel transcendentalist generation. He was ignored by Santayana’s student Conrad Aiken, whose 1924 reevaluation of Dickinson portrayed her as an independent, symbolist freethinker who resisted the call to “sew for soldiers, join a Browning club, and recite Hiawatha.” To the new generation of Modernists, “Dickinson was avant-garde, Higginson an heirloom.”

Higginson was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, his casket wrapped in the First South Carolina regimental flag. His pallbearers were African-American men, members of the Sixth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (Colored). His headstone simply notes his rank and his service to the country’s pioneering combat soldiers of African descent. (A plaque commemorating him and his regiment is on a highway in Beaufort, S.C. ) “The pendulum has … swung far from him, and he is hardly remembered,” Wineapple notes. In “White Heat,” she reminds us who he was.

As for Emily. … Check the canon.

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection “Stealing the Fire,” is president of the National Book Critics Circle. Two of her abolitionist forebears served as chaplains for black regiments in the Union Army.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.